Abetment

What is Abetment?

Abetment is a preparatory act and connotes active complicity on the part of the abettor at a point of time prior to the actual commission of the offence.[1] According to Black’s Law Dictionary; to 'abet' is "to encourage and assist someone, especially in the commission of a crime, or to support a crime by active assistance”. The term 'abetment' as defined by the Cambridge Dictionary is the 'act of helping or encouraging someone to do something illegal or wrong.'[2]

In Corpus Juris Secundum, 'to abet has been defined as meaning to aid; to assist or to give aid; to command, to procure, or to counsel; to countenance; to encourage, counsel, induce, or assist; to encourage or to set another on to commit.'[3]

Official Definition of 'Abetment’

Section 3(1) of the General Clauses Act, 1897, provides 'abet, with its grammatical variations and cognate expressions, shall have the same meaning as in the Indian Penal Code.'

Abetment as Defined in Legislations

Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023

'Abetment of a thing' as defined under Section 45 of BNS (Section 107, IPC) lies as follows:

A person abets the doing of a thing, who—

- (a) Instigates any person to do that thing; or

- (b) Engages with one or more other person or persons in any conspiracy for the doing of that thing, if an act or illegal omission takes place in pursuance of that conspiracy, and in order to the doing of that thing; or

- (c) Intentionally aids, by any act or illegal omission, the doing of that thing.

Who is an Abettor?

An abettor is a person who instigates, aids, or encourages another person to commit a crime. The abettor is held criminally liable even if they did not directly commit the offense. Section 46 of BNS (Section 108 of IPC) states that, a person abets an offence, who abets either the commission of an offence, or the commission of an act which would be an offence, if committed by a person capable by law of committing an offence with the same intention or knowledge as that of the abettor.

POCSO Act, 2012

As per Section 16 of the Act, a person abets an offence, who—

- First, Instigates any person to do that offence; or

- Secondly, Engages with one or more other person or persons in any conspiracy for the doing of that offence, if an act or illegal omission takes place in pursuance of that conspiracy, and in order to the doing of that offence; or

- Thirdly, Intentionally aids, by any act or illegal omission, the doing of that offence

Terrorist And Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act, 1987 [Repealed]

The definition of the word 'abet' as defined under Section 2(1)(a) of the Act is as follows:

In this Act, unless the context otherwise requires, 'abet' with its grammatical variations and cognate expressions, include

- The communication or association with any person or class of persons who is engaged in assisting in any manner terrorists or disruptionists;

- The passing on, or publication of, without any lawful authority, any information likely to assist the terrorists or disruptionists and the passing on, or publication of, or distribution of, any document or matter obtained from terrorists or disruptionists;

- The rendering of any assistance, whether financial or otherwise, to terrorists or disruptionists

Legal Provisions Relating to Abetment

Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023

Extraterritorial Abetment

Section 108A of IPC puts abetment of offences to be committed outside India on the same footing as the abetment of offences to be committed in India. Under this section, although the offence abetted may be committed outside India, the abetment itself must be committed in India. IPC Only talks about abetment done in India for a crime that happens outside India, provided that the act must be a crime both under Indian law and in the country where it’s committed.

However, BNS goes a step further, clearly covers both scenarios and establishes the territorial scope of liability for abetment, ensuring that abettors cannot escape punishment merely due to the cross-border nature of their involvement:

Under Section 47, BNS, if a person located in India abets the commission of an act that takes place outside India, they will still be deemed to have abetted an offence under the Sanhita—provided that the act would constitute an offence if it were committed within India. Conversely, Section 48, BNS, states that if a person, from outside India, abets the commission of an act that occurs in India and qualifies as an offence under Indian law, they too shall be considered to have abetted the offence under this statute. Together, these provisions ensure that abetment is punishable regardless of the geographical location of the abettor or the act, so long as the act is criminal under Indian law.

Punishment for Abetment

Sections 49, 55, 56, and 57 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita outline the punishment for abetment in depending upon whether the act is either committed or not committed, and where no specific provision for such abetment exists:

Section 49, BNS provides that if an act is actually committed as a result of abetment and the law does not expressly prescribe punishment for that abetment, the abettor will still be punished with the same penalty as that of the principal offence. Section 55 of BNS addresses situations where an offence punishable with death or life imprisonment is abetted, but is not ultimately committed; in such cases, the abettor may be punished with up to seven years of imprisonment and a fine. However, if the abetment leads to an act that causes hurt, the punishment increases to up to fourteen years of imprisonment and a fine.

Section 56, BNS applies similarly where the abetted offence is punishable with imprisonment, but remains uncommitted; in such cases, the abettor may face up to one-fourth of the maximum punishment prescribed for that offence. This may extend to one-half if the abettor or the person abetted is a public servant charged with preventing the offence, thereby imposing stricter liability due to their official duty. Lastly, Section 57, BNS imposes punishment on those who abet the commission of an offence by the general public or by a group exceeding ten persons, with imprisonment extending up to seven years along with a fine.

Collectively, these provisions ensure that abettors are held accountable not just for the outcomes of their instigation, but also for the potential consequences and gravity of the offences they seek to incite, even if not fully carried out.

Liability of Abettor

Sections 50 to 54 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita elaborate on the nuanced liability of an abettor when the act committed differs in nature, intention, or outcome from what was originally abetted:

Section 50, BNS provides that if the person abetted carries out the act with a different intention or knowledge than that of the abettor, the abettor will still be punished as if the act had been done with their own intention or knowledge—ensuring accountability based on the abettor’s original mental state. Section 51, BNS extends liability to cases where the abettor instigates one act, but a different act is committed as a probable consequence; in such cases, the abettor is held liable for the act actually done, provided it was influenced by the abetment or occurred in furtherance of the conspiracy.

Section 52, BNS further clarifies that if both the abetted act and the resulting act occur and constitute distinct offences, the abettor may be punished separately for each. Under Section 53, BNS, even if the abettor intended a specific result but a different effect occurred due to the abetted act, the abettor remains liable for the actual effect caused—if it was foreseeable. Finally, Section 54, BNS states that if the abettor is physically present during the commission of the offence, they are no longer treated merely as an abettor but are deemed to have committed the offence themselves. Together, these provisions ensure that abettors cannot escape liability simply because of unexpected variations in the acts or outcomes arising from their instigation or involvement.

Abetment of Suicide

Sections 107 and 108 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023, deal with the offence of abetment of suicide, but with differing degrees of punishment based on the vulnerability of the victim:

Under Section 107, BNS, if a child, a person of unsound mind, a delirious individual, or someone in a state of intoxication commits suicide, the person who abets such suicide is punishable with death, life imprisonment, or imprisonment for a term up to ten years, along with a fine. This harsher penalty reflects the increased culpability when the victim is particularly vulnerable or incapable of rational judgment.

In contrast, Section 108, BNS covers abetment of suicide of any other person not falling into these special categories and prescribes a relatively milder punishment of imprisonment for a term that may extend up to ten years, along with a fine. The distinction between the two provisions lies in the mental and physical state of the victim, with Section 107 ensuring greater protection for those deemed unable to fully comprehend or resist abetment.

In the case of Sanadi v. State of Karnataka [2024], the accused was convicted for abetting the suicide of a woman. The facts showed that the conduct of the accused was consistent with continuous harassment, threats, and mental cruelty, which eventually led the woman to take her own life. The prosecution proved that the accused’s actions were of such a nature that they intentionally provoked or instigated the deceased into ending her life.

Sections 159 to 163 deal with the abetment of offences by members of the armed forces of India. They prescribe stringent punishments for those who abet mutiny or attempt to seduce an officer, soldier, sailor, or airman from their duty or allegiance, with penalties extending up to life imprisonment under Section 159, BNS, and even death if mutiny actually occurs as a result of such abetment under Section 160, BNS. Abetment of assault on a superior officer by armed forces personnel is also criminalized, carrying up to three years of imprisonment, which increases to seven years if the assault is committed due to such abetment (Sections 161 and 162, BNS). Additionally, Section 163, BNS punishes abetment of desertion with imprisonment up to two years, or fine, or both. Collectively, these provisions underscore the gravity with which the law treats any encouragement or facilitation of indiscipline within the military ranks.

Provisions Under Other Statutes

Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988

Section 12 of the Act provides Punishment for abetment of any offence under the Act - If someone helps, supports, or encourages another person in committing corruption (like taking or giving bribes), they will be punished whether or not that offence is committed in consequence of that abetment. Such an act shall be punishable with imprisonment for a term which shall be not less than three years, but which may extend to seven years and shall also be liable to fine.

Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act, 1985

Section 29 of NDPS Act accords Punishment for Abetting Drug Crimes - If a person helps, plans, or conspires with others to commit a drug-related crime (such as smuggling, selling, or producing illegal drugs), they will face the same punishment as the main criminal, even if the crime doesn’t actually happen. This applies even if the planning happens in India for a drug crime to be committed in another country, as long as that act is illegal in both places.

Dowry Prohibition Act, 1961

Section 3 of the Dowry Prohibition Act, 1961 provides Punishment for Giving or Taking Dowry - If any person gives or takes or abets the giving or taking of dowry, he shall be punishable, term which shall not be less than five years, and with fine which shall not be less than fifteen thousand rupees or the amount of the value of such dowry, whichever is more.

Further, Section 8A of the Act provides for Burden of Proof in the aforementioned scenario - Where any person is prosecuted for taking or abetting the taking of any dowry under section 3, or the demanding of dowry under Section 4, the burden of proving that he had not committed an offence under those sections shall be on him.

Abetment as Defined in Case Law(s)

Abetment by Instigation

Sanju @ Sanjay Singh Sengar vs State Of M.P [2002]

in the case of Sanju @ Sanjay Singh Sengar vs State Of M.P [2002][4], the Court evaluated whether the accused’s statement “go and die” constituted instigation under Section 107 of the IPC. The Court held that even if such words were spoken, they do not in themselves amount to instigation. Two important takeaways can be gathered from this judgment.

- "The word 'instigate' denotes incitement or urging to do some drastic or unadvisable action or to stimulate or incite. Presence of mens rea, therefore, is the necessary concomitant of instigation. It is common knowledge that the words uttered in a quarrel or in a spur of the moment cannot be taken to be uttered with rea. It is in a fit of anger and emotional.

- There was a gap of two days between the quarrel and the suicide, which breaks the chain of causation. This time gap indicates that the suicide was not the direct or proximate result of the accused's alleged statement.

The Court, hence, concluded that the statement “go and die,” made in a moment of anger during a quarrel, without any sustained incitement or malicious intent, does not satisfy the legal threshold of ‘instigation’ under Section 107 IPC. With similar facts of the case, the Supreme Court, in Swamy Prahaladdas v. State of M.P. & Anr. [1995], was of the view that mere words uttered by the accused to the deceased 'to go and die' were not even prima facie enough to instigate the deceased to commit suicide.

R. v. Mohit Pande [1871]

In R. v. Mohit Pande (also see Fuguna Kant v. State of Assam [1959][5]), the court held that silent approval, if it produces an effect of incitement, constitutes abetment by instigation. In this case, a woman had prepared herself for Sati (self-immolation). A group of individuals followed her to the cremation ground and stood by her funeral pyre. While doing so, they repeatedly chanted "Ram, Ram," and the accused also encouraged the woman to say "Ram, Ram." The court found that their actions amounted to active participation and connivance in the act, leading to the conclusion that they were guilty of abetment, as they effectively encouraged the woman to take her own life by jumping into the fire.

Queen-Empress v. Sheo Dial Mal [1894]

This case held that instigation may be direct or it may be through letter. Where A writes a letter to B instigating thereby to murder C, the offence of abetment by instigation is complete as soon as the contents of letter becomes now to B.

Brij Lal vs. Prem Chand & Anr [1989]

The Supreme Court, in the case of Brij Lal vs. Prem Chand & Anr [1989][6], held that an act of abetment cannot be viewed or tested in isolation. The instigative words should be judged based on the distraught condition to which the accused had driven the victim.

Abetment of Suicide

Directness of the Abetment

Prakash & Others v. The State of Maharashtra & Another [2024]

The Supreme Court, in Prakash & Others v. The State of Maharashtra & Another [2024][7], examined the concept of abetment under Section 306 of IPC in a case where the appellants were accused of abetting a woman's suicide due to alleged harassment and dowry demands. The Court emphasized that for abetment to be established under Section 107 IPC, there must be clear evidence of instigation, conspiracy, or intentional aid leading directly to the suicide. Mere marital disputes or harassment, without a direct link to the act of suicide, do not constitute abetment. Since the prosecution failed to prove a proximate connection between the accused's actions and the deceased's decision to take her life, the Court discharged the appellants. This ruling reinforces that general allegations of harassment are insufficient to sustain charges of abetment of suicide.

Pawan Kumar v. State of H.P. [2017]

In the case of Pawan Kumar v. State of H.P. [2017][8], in reference to the case of Chitresh Kumar Chopra v. State (Government of NCT of Delhi) [2009], the Supreme Court analyzed the concept of "abetment" under Section 107 of the Indian Penal Code (IPC). The court highlighted three ways in which a person can be said to have abetted the commission of an offense:

First, instigation, where a person encourages or provokes another to commit the offense. This could be through direct or indirect means, such as verbal suggestions or implied conduct. The word "instigate" was elaborated to mean urging, provoking, or encouraging someone to act. Second, abetment by conspiracy, where two or more individuals engage in a conspiracy to commit an offense. If an act or illegal omission takes place in furtherance of that conspiracy, it amounts to abetment. Third, abetment by intentional aiding, where a person intentionally aids or assists in the commission of an offense, either through acts or omissions.

The court clarified that 'any wilful misrepresentation or wilful concealment of material fact which he is bound to disclose, may also come within the contours of “abetment”.' It further clarified that in cases involving suicide, direct involvement of the person or persons concerned in the commission of offence of suicide is essential to bring home the offence under Section 306, IPC (Section 108, BNS).

Bar of Proof

M. Mohan vs State [2011]

In the case of M. Mohan vs State [2011][9], the Supreme Court set a high bar for proving abetment of suicide, including specific intent. The court emphasized that for conviction under Section 306 of the IPC, there must be clear mens rea—the intention to provoke or drive the victim to suicide.

Moreover, there must be an active or direct act by the accused that left the deceased with no reasonable alternative but to end their life & this act must be shown to have been intended to place the deceased in such a helpless situation that suicide became the only perceived option.

Ude Singh v State of Haryana [2019]

This standard was upheld in Ude Singh v State of Haryana [2019][10] as well, where the Supreme Court stated that -

"There must be a proof of direct or indirect act(s) of incitement to the commission of suicide. If the accused by his acts and by his continuous course of conduct creates a situation which leads the deceased perceiving no other option except to commit suicide, the case may fall within the four corners of Section 306 IPC."

Suicide Note

Manikandan v State [2016]

The case of Manikandan v State [2016][11]was a landmark judgement where the court held that the mere mention of a person in a suicide note would not make him or her accountable for abetment to suicide. To invoke Section 306 the suicide letter needs to be scrutinized carefully first. The court further stated that it is not the wish and willingness nor the desire of the victim to die, it must be the wish of the accused, it is the intention on the part of the accused that the victim should die that matters much. There must be a positive act on the part of the accused.

Mahendra Awase vs State of M.P. [2025]

The case of Mahendra Awase vs State of M.P. [2025][12] involved Awase, accused of abetment after a suicide note mentioned he was harassing the deceased over a loan. However, the Court found no instigation or active role on Awase's part. Demanding loan repayment as part of one’s job cannot amount to abetment, it said. The Court stressed that mere allegations or emotional reactions should not lead to prosecution unless there is clear evidence of intent and direct involvement in provoking the suicide.

The Supreme Court held that Section 306 IPC (abetment of suicide) should not be invoked casually or mechanically just to satisfy grieving families. The Court emphasized that only in genuine cases where the legal threshold is met should prosecution proceed. It criticized police and trial courts for frequently misusing this provision and urged them to act with sensitivity and caution, avoiding a “play-it-safe” approach.

Types of Abetment

Forms of Abetment

Abetment, as describes under Section 45 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) (previously Section 107 of IPC), refers to the intentional encouragement, assistance, or facilitation of an offense. This may take the form of instigating, conspiring, or intentionally aiding in the commission of a crime—either by: providing support, resources, or assistance, or even failing to act, when there exists a legal duty to prevent the offense.

Abetment by Instigation

In common language, it means to goad or urge forward or to provoke, incite or encourage in doing something. Section 45 of BNS explains the term instigation. According to it, “If a person legally bound to disclose a material fact, willfully or by willful misrepresentation conceals it and voluntarily causes or procures or attempts to cause or procure a thing to be done, he will be said to instigate the doing of that thing"

Abetment by Conspiracy

This involves an agreement between two or more people to commit an offense. However, mere conspiracy does not constitute abetment until any act or illegal omission is done in pursuance of that conspiracy. In abetment by conspiracy, it is not necessary that the abettor keep in touch with the main offender. It is sufficient that he participates in the conspiracy, in pursuance of which the offence was committed

Abetment by Intentional Aiding

This occurs when a person intentionally provides assistance, resources, or support to someone committing an offense. Simply providing aid, without the intention to facilitate the offense, does not amount to abetment. The act of abetment encompasses both active and passive omissions and includes situations where a person intentionally fails to act in situations where they have a legal or moral obligation to do so, thereby facilitating the commission of an offense.

Slight Differences and Nuances to Abetment

The word conspiracy originates from the word conspire, which means to plot or scheme together which means the "joint participation" of several persons in a scheme or plot. The literal meaning persists in the legal definition of the offence or conspiracy whereby one person alone can never be guilty of criminal conspiracy for the simple reason that one cannot conspire with oneself. Section 61 of BNS (Section 120A, IPC) provides for criminal conspiracy and defines it as follows:

"When two or more persons agree with the common object to do, or cause to be done (a) an illegal act; or (b) an act which is not illegal by illegal means, such an agreement is designated a criminal conspiracy— provided that no agreement except an agreement to commit an offence shall amount to a criminal conspiracy unless some act besides the agreement is done by one or more parties to such agreement in pursuance thereof."

For constituting criminal conspiracy, two or more persons are required because only person cannot conspire with oneself. As in Topandas V. State of Bombay [1955][13]. it was enunciated that two or more persons must be parties to such an agreement and one persons alone can never be held guilty of criminal conspiracy for the single reason that one cannot conspire with oneself. The primary goal of criminal conspiracy is to commit an offence and achieve the desired result through illegal means. Criminal conspiracy can take many forms, such as plotting a robbery, carrying out a murder, or spreading false information to smear someone’s reputation.

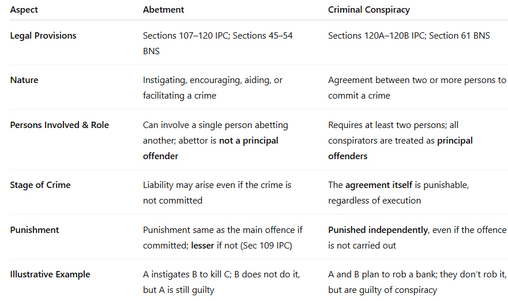

The case of Noor Mohammad Momin v. State of Maharashtra [1970][14] put forth the difference between criminal conspiracy and abetment to conspiracy and specified that criminal conspiracy has much broader scope and jurisdiction than abetment as just an agreement between people to commit an offence can constitute criminal conspiracy. The distinction with abetment can be better understood through the following illustration:

Research that engages with Abetment

The Innocent Abettor - A Comprehensive Study of Section 111 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 [International Journal of Law Management & Humanities]

This article "The Innocent Abettor - A Comprehensive Study of Section 111 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860" by Sanjana Nayak[15] delves into Section 111 of the IPC that establishes that an abettor can be held liable for an act that differs from the one they initially abetted, provided the act committed was a probable consequence of the abetment and was carried out under its influence. This principle is grounded in the ‘rule of agency,’ where the person who commits the act (the principal) is considered to be acting on behalf of the abettor (the agent).

Under this rule, the abettor is deemed responsible for the actions of the principal, even if those actions extend beyond the original plan, as long as they are a natural and probable outcome of the abetment. The law presumes that individuals intend the foreseeable consequences of their actions. Therefore, if the principal's act is a likely result of the abettor’s instigation, the abettor bears liability for that act.

This approach ensures that abettors cannot evade responsibility simply because the final act committed was not exactly what they had intended. The focus is on the foreseeability of the outcome and the influence of the abetment, reinforcing the accountability of those who encourage or assist in criminal activities.

Related Terms

Criminal Conspiracy

Section 61 of BNS (Section 120A, IPC) provides for criminal conspiracy and defines it as "When two or more persons agree with the common object to do, or cause to be done (a) an illegal act; or (b) an act which is not illegal by illegal means, such an agreement is designated a criminal conspiracy— provided that no agreement except an agreement to commit an offence shall amount to a criminal conspiracy unless some act besides the agreement is done by one or more parties to such agreement in pursuance thereof."

Know More: Criminal Conspiracy

References

- ↑ Black's Law Dictionary 5 (6th ed.) https://karnatakajudiciary.kar.nic.in/hcklibrary/PDF/Blacks%20Law%206th%20Edition%20-%20SecA.pdf

- ↑ Cambridge Dictionary. "Abetment" https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/abetment

- ↑ Corpus Juris Secundum, Vol. I 306

- ↑ Sanju @ Sanjay Singh Sengar vs State Of M.P, AIR 2002 SUPREME COURT 1998

- ↑ Fuguna Kant v. State of Assam, AIR 1959 SC 673.

- ↑ Brij Lal vs. Prem Chand & Anr, 1989 SCR (2) 612

- ↑ Prakash & Others v. The State of Maharashtra & Another, SLP (Crl.) No.1073 of 2023.

- ↑ Pawan Kumar v. State of H.P., 2017 (7) SCC 780

- ↑ M. Mohan vs State, 2011 (3) SCC 626

- ↑ Ude Singh v State of Haryana, AIR 2019 SUPREME COURT 4570

- ↑ Manikandan v State, Crl.A.(MD)No.142 of 2016

- ↑ Mahendra Awase vs State of M.P., CRIMINAL APPEAL NO. 221 OF 2025

- ↑ Topandas v. State of Bombay, 1955 SCR (5) 881

- ↑ Noor Mohammad Momin v. State of Maharashtra, 1971 SCR (1) 119

- ↑ Nayak, Sanjana. 2020. “The Innocent Abettor -A Comprehensive Study of Section 111 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860" International Journal of Law Management & Humanities (Vol. 3 Issue 3) https://ijlmh.com/wp-content/uploads/The-Innocent-Abettor-A-Comprehensive-Study-of-Section-111-of-the-Indian-Penal-Code-1860.pdf