Arrest

This page is now open for community updates

An arrest is a procedure in a criminal justice system which is caused by using legal authority to deprive an individual of freedom of movement. The arrestee is taken into custody for questioning, to safeguard from influencing/threatening witnesses or destruction of evidence, to prevent escape or for evading the due process of law etc. Probable cause of an arrest is a reasonable belief of the police officer in the guilt of the suspect, based on the facts and information prior to the arrest. For instance, an arrest may be legitimate in situations where the police officer has a reasonable belief that the suspect has either committed a crime or is about to commit a crime. Police and various other officers have powers of arrest although certain conditions must be met before taking such action. As a safeguard against the abuse of power, it requires that an arrest must be made for a thoroughly justified reason.

Official Definition of Arrest

According to Black's Law dictionary, arrest means 'to deprive a person of his liberty by legal authority. Taking, under real or assumed authority, custody of another for the purpose .of holding or detaining him to answer a criminal charge or civil demand'.[1]

Arrest as defined in Legislation(s)

Under Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS)

Despite not being explicitly defined in procedural or substantive Acts, the process of arrest is detailed in Chapter V of Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS) 2023, from Sec. 35 to Sec. 62, which outlines the power and procedure of arrest, the use of handcuffs, and the duties and responsibilities of a police officer making an arrest. This enables the Investigating Officer (lO) or Police Officer to obtain clues and evidence to reach a logical conclusion. The seizure of articles from the possession of the accused and materials collected leading by means of discovery have always been proved to be immensely useful in investigation of a criminal case.

Under Special Laws

In addition to the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS), arrest can also be made under special statutes such as Section 43B of the Unlawful Activities and Prevention Act, Section 19 of the Prevention of Money Laundering Act, Section 52 of the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act, 1985 etc. The arrest is governed by the process provided within the special statutes.

Legal Provisions relating to Arrest

Arrest by Police

Arrest with Warrant

Broadly, arrest of persons may be classified under two categories arrests under warrants issued by a competent court; and arrests otherwise than such warrants. Arrests with a warrant, a more prevalent scenario, empower the police to detain individuals who are unwilling to appear before the court upon receiving a summon. A warrant for arrest is required by the police to arrest in non-cognizable cases, as defined under Section 2(l)(o) of the BNSS. A warrant may be bailable or non bailable. A bailable warrant permits the person arrested to provide surety to secure release from custody, under Section 73 of BNSS. These contain directions from the Court over the amount of sureties. On the other hand, a non-bailable warrant does not contain directions for grant of bail, which means that the accused cannot secure release from police custody and must appear before the court to apply for bail.

An arrest with warrant is made under Section 35(2) of BNSS which explicitly prohibits police from arresting a person concerned in a non-cognizable offence “except under a warrant or order of a Magistrate,” subject to special exceptions stated in Section 39 BNSS. Section 39 BNSS provides that when a person accused of a non-cognizable offence refuses or fails to provide their true name and residence, the police officer may arrest them temporarily to ascertain their identity. After confirming the true name and residence, the police must release the person upon their executing a bond or bail bond, with or without sureties, as a guarantee for their appearance before a Magistrate when required. This bail bond acts as a legal assurance that the person will comply with judicial processes following their release. Moreover, if the accused is not an Indian resident, the bail bond must be secured by surety or sureties who are Indian residents, ensuring there is a responsible party within the jurisdiction to guarantee attendance. If the true identity cannot be established within 24 hours, or if the accused fails to provide the required bond or sureties, the individual must be promptly produced before the nearest Magistrate for further directions. This structured process safeguards individual liberty while balancing the necessity of establishing accurate identity and ensuring judicial oversight.

Further, Section 82 (2) of BNSS requires that a police officer arresting a person on the strength of a warrant must immediately inform a designated police officer in the district and another district where the arrested person normally resides.

Arrest without Warrant

Immediate Arrest

Under Section 35(1) of BNSS, A police officer can arrest any person falling under the following categories can be arrested without warrant.

- Who commits a cognizable offence in the presence of a police officer.

- A proclaimed offender.

- Someone in possession of anything suspected to be stolen property, having committed an offence concerning such property.

- Someone who obstructs a police officer in the execution of their duty or escapes or attempts to escape from lawful custody.

- A deserter from the Armed Forces.

- Someone against whom an order of extradition or other detainment has been issued.

- A released convict who breaches any rule under Section 394(5)

- Someone against whom a requisition for arrest has been received from other police officers under Section 55(1) of BNSS.

Arrest during investigation

- For cognizable offences punishable upto Seven years imprisonment When the punishment provided for cognizable offence is less than seven years the arresting investigating officer while effecting the arrest shall record his satisfaction regarding commission of offence by the accused/suspect and the requirement for arrest as per Section 35(1)(b).The police officer shall record while making such arrest' his reasons in writing in the Case diary and if the arrest is not made, the reasons thereof shall also be recorded in the case diary.

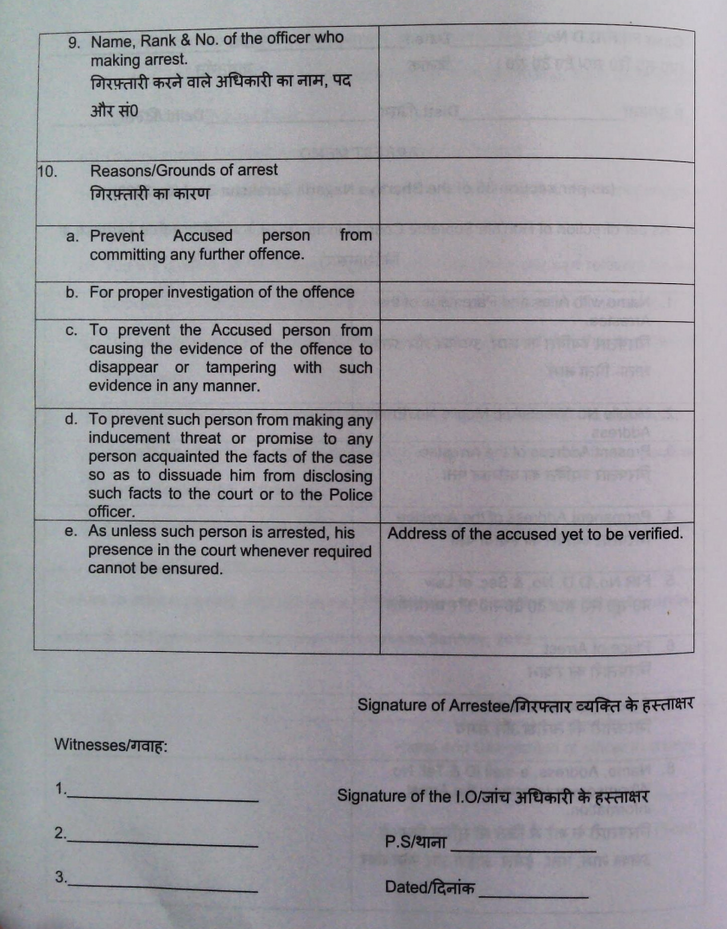

- If arrest is required An arrest can be made as per Section 35(1)(b) if investigating officer has reason to believe that such person has committed the said offence, and the police officer is satisfied that such arrest is necessary in view of reasons mentioned in Section 35(1)(b)(ii), as stated below:

- To prevent such person from committing any further offence; or

- For proper investigation of the offence; or

- To prevent such person from causing the evidence of the offence to disappear or tampering with such evidence in any manner; or

- To prevent such person from making any inducement, threat or promise to any person acquainted with the facts of the case so as to dissuade him from disclosing such facts to the Court or to the police officer; or

- As unless such person is arrested, his presence in the Court whenever required cannot be ensured.

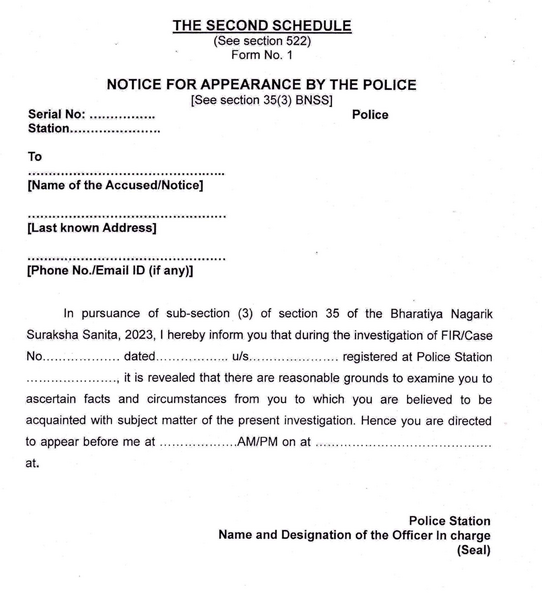

- If arrest is not required A notice of appearance is an alternate remedy if arrest is not required. Section 35(3) BNSS provides that when arrest is not required under Section 35(1) or (2), the police officer shall issue a notice of appearance to the person concerned. The person must appear before the officer at the time and place specified in the notice. If the person complies, he shall not be arrested unless the officer records reasons in writing. The investigating officer can issue notice to accused persons in all cognizable cases where the arrest of the person is not required under Section 35(3) of BNSS (Section 41A of erstwhile CrPC). As per Section 35(4) the person must comply with the terms of the notice issued. Compliance with such notice protects the accused from arrest unless reasons are later recorded under Section 35(5) and If person fails to comply with the terms of the notice, police may arrest for reasons to be recorded as per Section 35(6) of BNSS. The reasons for arrest or non-arrest, and the notice issued, must be forwarded to the Magistrate, for scrutiny at the time of first production/remand. Magistrate must examine these reasons before authorising remand. BNSS allows electronic service of notice. A notice can be issued through electronic means such as email, SMS or digital platforms notified by the State. The compliance and reasons for arrest can now be maintained in electronic form as part of the digital case diary system under the BNSS. This brings transparency, reduces tampering, and leaves a traceable record of police conduct.

Notice of Appearance u/s 35(3) of BNSS

- If arrest is required An arrest can be made as per Section 35(1)(b) if investigating officer has reason to believe that such person has committed the said offence, and the police officer is satisfied that such arrest is necessary in view of reasons mentioned in Section 35(1)(b)(ii), as stated below:

- For cognizable offences punishable with more than Seven years imprisonment. Section 35(1)(c) of BNSS provides for arrest of a person against whom credible information has been received that he/she has committed a Cognizable offence punishable with imprisonment for a term which may extend to more than seven years, whether with or without fine, or with death sentence and the Police officer has reason to believe on the basis of that information that such person has committed the said offence.

Arrest for refusing to give identity

Section 39 of BNSS provides for arrest without warrant if a person is accused of committing a non-cognizable offence, on demand by the police officer do not disclose name and address or such officer has reason to belief that the name and address provided is false, the police officer may arrest them solely for the purpose of ascertaining their true identity. Once the true name and residence are ascertained, the person must be released upon executing a bond or bail bond, with or without sureties, to appear before a Magistrate if required. If the person is not a resident of India, the bail bond must be secured by a surety or sureties who are residents of India. If the true name and residence cannot be ascertained within 24 hours of arrest, or if the person fails to execute the bond or furnish sufficient sureties, they must be promptly produced before the nearest Magistrate having jurisdiction.

Preventive Arrests (Detention)

Section 170 of BNSS empowers a police officer to arrest a person without a warrant if they have knowledge of a potential commission of cognisable offence and believe that the commission of offence cannot be otherwise prevented. The officer must have knowledge of the design to commit the offence and believe that the crime cannot be prevented otherwise. A person arrested under this provision cannot be kept in custody for more than 24 hours unless a different law allows it. This clause protects human rights and prevents illegal or prolonged detention.

Arrest by Private Person

Section 40 of BNSS provides the circumstances and the process through which a private citizen can detain a person who has committed some of the specified offences in his presence. The provision is of particular importance since it empowers the private citizen to act in cases where police action is not readily available or possible, thus ensuring prompt action against the offenders. The arrested person should be handed over without any delay or taken to the nearest police station to a police officer within six hours from the arrest. If there is a reasonable ground for believing that the arrested person falls within the ambit of section 35(1) BNSS, which details offences for detention is authorised; then a police officer should take such arrested person into custody. This ensures that the person arrested is forwarded to the competent authority once a private person has made an arrest.

In cases of non-cognizable offence, if the arrested person refuses to give his name and residence or, if the name and residence given are false, he shall be dealt with under Section 39 BNSS. In case there is not sufficient cause for believing that an offence has been committed, the arrested person shall forthwith be released. This ensures the rights of the individual are protected, and the arrest does not result in unjust detention.

Arrest by Magistrate

Magistrates, both executive and judicial, has the power to arrest individuals within their jurisdiction as per Section 41 of BNSS (Section 44 of erstwhile CrPC). If any offence, regardless of whether it is cognizable or non-cognizable, is committed in the presence of a Magistrate and it falls within the Magistrate’s local jurisdiction, the Magistrate has the ability to either arrest the individual themselves or order someone else to do so. Once a person has been apprehended, the Magistrate has the authority to commit them to detention in accordance with the law and the requirements of bail. This authority is expanded by Section 41(2), which states that a Magistrate can arrest or order the arrest of a person in their presence and within their local jurisdiction at any time, even if they did not witness the offence. This is provided that the Magistrate has the authority to issue a warrant for that person in the circumstances that are described in the section.

Formal Arrest

A formal arrest is one that is made according to Section 43 of the BNSS (S. 46(1) of the CrPC ). Accordingly, Actual arrest can be effected by the following means:

- By using words, actions, touching, or confining the body of the person to be arrested to take them into custody.

- In other words, it is a legal process that circumscribes the liberty of an individual and prevents them from moving beyond without the permission of the police officer or court.

- A police officer may use all necessary means to effect the arrest if the person forcibly resists or attempts to evade arrest (Sec. 43 (2) BNSS).

Further, while making an arrest the procedure prescribed in Section 36 of BNSS should be strictly followed. The provision requires the police officer making the arrest to bear an accurate, visible, and clear identification of their name. Section 36(b) of BNSS also requires an Arrest memo to be also prepared.

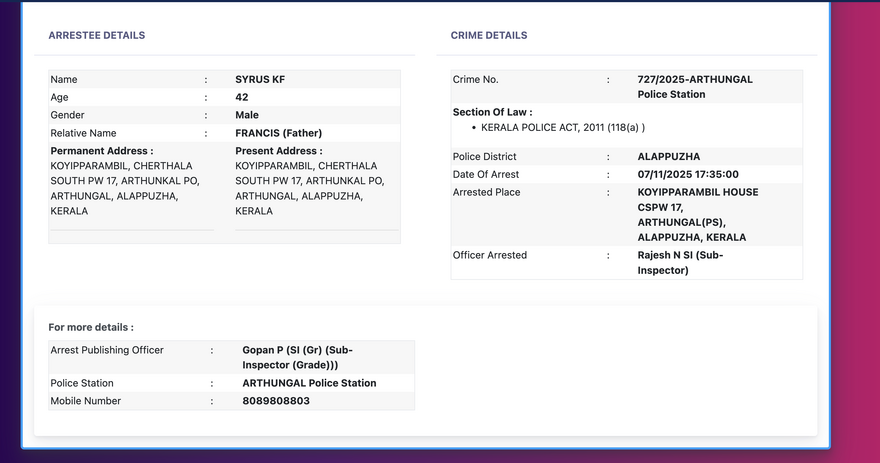

Arrest memo

Section 36(b) of BNSS also requires an Arrest memo to be also prepared. An arrest memo is a formal written document prepared by the police officer at the time of arrest. It records important details such as the name of the person arrested, the time, date, and place of the arrest, the reasons for the arrest, and the suspected offence. This memo serves as an official record to ensure that the arrest is legal and transparent, protecting the arrested person against illegal detention or abuse.

Section 36(b) of BNSS mandates that Arrest memo shall be:

- Attested by at least one witness, either belonging to the arrested person or a respectable member of the locality where the arrest is made.

- Countersigned by the person arrested.

- If the Memorandum of Arrest is not signed by family members, the police officer shall inform the arrestee of their right to have a relative, or a friend or any other person named by him to be informed of his arrest.

Search and Seizure at the time of arrest

Search of place entered by person sought to be arrested

Section 44 of the BNSS governs the powers of law enforcement officers to enter and search premises to make an arrest. When an officer has a warrant or legal authority to arrest a person believed to be inside a location, they can demand entry and search the premises. The person in charge must allow entry and provide reasonable facilities for the search. If entry is refused, the officer may forcibly enter by breaking doors, windows, or barriers, but only after clearly notifying their authority and purpose.

The section includes special protections for women observing purdah, requiring officers to inform them and give sufficient time and space to withdraw before entering. Additionally, if officers or other authorized persons are wrongfully confined inside, they may break out of any exit to secure their release and proceed with the arrest.

Search of arrested person (jama talayshi)

Section 49 of the BNSS deals with the search of an arrested person and the handling of any personal items found on them in the following situations:

- When a person is arrested by a police officer under a warrant that does not allow bail.

- When a person is arrested under a warrant that permits bail but the person arrested is unable to furnish bail.

- When a person is arrested without a warrant or is arrested by a private person under a warrant and cannot legally be admitted to bail or is unable to furnish bail.

In these situations, the arresting officer or the police officer who takes over the arrested person can search them. The search allows the officer to take into safe custody any articles found on the person, except for necessary clothing. If anything is taken, the arrested person must be given a receipt listing the items. Additionally, if the person searched is a woman, the search must be conducted by another female officer with strict regard to decency to protect privacy.

According to Section 49(2) If the person to be searched is female, the search must be conducted by another woman, ensuring that decency is maintained throughout the process.

Section 50 of the BNSS gives the police or any person making an arrest the immediate power to take away any offensive weapons found on the arrested person. This means that as soon as a person is arrested, the officer can seize any dangerous weapons they have on them, such as knives, firearms, or other weapons that could cause harm. The weapons taken from the arrested person must be handed over to the court or the officer before whom the arrested person is produced.

Under Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances (NDPS) Act, 1985, the person who is arrested should be informed, as soon as may be, the grounds of his arrest. If the arrest or seizure is based on a warrant issued by a magistrate, the person or the seized article should be forwarded to that magistrate in accordance with Section 52 (1) of NDPS Act. Further, Section 57 of NDPS act provides that the officer who arrests a person has to make a full report to his official superior within 48 hours.

Rights of Arrested person

Person arrested to be informed about the grounds of arrest

Section 47 of BNSS protects the arrested person’s right to know why they are being taken into custody right at the time of arrest. When a person is arrested without a warrant, the police officer or the person making the arrest must immediately tell that person exactly why they are being arrested— share full details about the offence or the reason for the arrest. If the offence is bailable, the arrested person should also be informed that they have the right to be released on bail and can arrange sureties for the same.

Obligation to inform arrest to relatives and friends

Section 36(c) of BNSS obligates the police officer making an arrest to inform the arrested person of their right to have a relative, friend, or any other person named by them informed about their arrest. Further, a police man is also obligated to issue written notice under section 48(1) of BNSS about the place and details of arrest to his relatives, friends or persons nominated by arrestee and to the designated Police Officer in the district. An entry must be made in the General diary about arrest and to whom the arrest is informed under section 48(3) of BNSS.

Further Chandigarh Administration[2] and Jammu & Kashmir[3] has notified Information of arrested persons Rules providing a form for person.

Person arrested not to be detained for more than twenty-four hours

Section 58 of BNSS responds well with the constitutionally protected measure provided under Article 22(2) of the Indian Constitution, which requires the arrested person be produced before the Magistrate concerned within twenty four hours after such arrest has been made. Section 58 deals with the legal provisions pertaining to the detention of a person arrested without a warrant. This section aims to safeguard the fundamental rights of the arrested person by imposing restrictions on the period of detention in police custody and providing proper judicial scrutiny.

It prohibits a police officer from detaining an arrested person in custody beyond twenty-four hours without getting a specific order from a Magistrate. That 24 hour period is excluded from the period of transporting an arrested person to the Magistrate's Court, and is calculated as starting with the moment of the arrest. The detention of the arrested person has to be deemed reasonable with regard to the facts and circumstances of the case. The police are allowed to seek remand from a Magistrate under the provisions of Section 187 BNSS, if they need more time to conduct their investigation.

Arrest Safeguards

The law of arrest balances two competing interests—the State’s power to investigate crimes and the individual’s right to liberty. To prevent unnecessary and arbitrary arrests, Parliament introduced safeguards under Section 41A of the Cr.P.C, 1973 (inserted by 2009 the Amendment). These safeguards are carried forward and strengthened in the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS) , 2023. Together, these provisions 3 safeguard personal liberty, prevent misuse of police power, and uphold the principle that arrest is an exception, not the rule.

Scrutiny at Remand Stages

Section 35(3) to (6) BNSS safeguard the constitutional right to liberty under Article 21, mandating the issuance of notice of appearance and recording of reasons for arrest and non-arrest. At the remand stage, the Judicial Magistrate plays a crucial role in ensuring that these safeguards are meaningfully enforced.

Special Requirements for different class of persons

Arrest of Women

The Arrest of Women should follow the following safeguards

- A woman can only be arrested by a female police officer.

- A male police officer shall not touch the body of a woman to make her arrest.

- No woman shall be arrested after sunset and before sunrise. In exceptional circumstances, a woman can be arrested by a Woman Police Officer after obtaining an order from the court within whose local jurisdiction the offence is committed or the arrest is to be made (Sec. 43 (5) BNSS).

Member of Armed Forces

Section 42 of BNSS bars the arrest of member of the Armed Forces of the Union for anything done in the discharge of official duties. However, the member of the Armed Forces can be arrested after obtaining consent /order of the Central Government.

Child in Conflict with Law

As per the Juvenile Justice Act, 2015, any minor who has committed a crime will be apprehended rather than detained or imprisoned.[4] A Child in Conflict with Law (CCL) shall, under no circumstances, be arrested by the police. Under India's Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015, and related provisions, a child (under 18 years) alleged to have committed an offence should generally not be apprehended except in cases of heinous offences or when necessary for the child's own protection. The law mandates that children should not be subjected to adult criminal procedures such as being kept in police lockups or jails, nor should they be handcuffed or physically restrained. Upon apprehension, the child must be produced before the Juvenile Justice Board within 24 hours, which takes into account the child's social background and circumstances to determine an appropriate course of action focusing on care, protection, and rehabilitation.

Pre-Arrest Judicial Intervention

An arrest cannot be made if there is interim protection or a stay has been granted by the courts. If the accused discloses that they have been granted 'Anticipatory Bail' by the court but no such order has been received by the investigating officer, the IO shall verify the authenticity of the accused's version and proceed accordingly.

Section 37 of BNSS (Section 41C of erstwhile CrPC) mandates Government to issue notification designating certain police officers to maintain information about arrested persons at the police station, district and state control rooms. An officer not below the rank of ASI shall be in charge. also The arrest be details will be displayed in the Police Station Control Room and will intimated to the District Control Room and State Control Room for public display. The control room shall maintain detailed information about arrested persons, including names, addresses and nature of the offence.

Further, Section 59 of BNSS mandates the Officer in-charge of Police Station to report cases of all persons arrested to theDistrict Magistrate, within their respective station limits, whether such persons have been admitted to bail or otherwise.

Compensation for wrongful arrest

The definition of wrongful arrest and the procedure for compensation on finding of an arrest to be wrongful is stated in Section 399 of the BNSS (Section 358 of erstwhile CrPC) protect citizens from being wrongfully arrested due to someone else’s false accusations. If the Magistrate determines that the arrest lacked sufficient justification, cause or reason in arrest of the accused, and that based on the facts of the case the accused is not the one to have committed an offence of any sort, the Magistrate can order compensation to be paid to the accused person arrested, to be paid by the person who causes such arrest by the Police officer. The compensation awarded s recovered just like a criminal fine and cannot exceed one thousand rupees.

Arrest as defined in official documents

Standing Orders by State police departments

States like Assam[5], Manipur[6], Meghalaya, Delhi,[7] Telangana, have formulated guidelines, standing order and circulars to regulate the arrest process. Some states like Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh etc.have formulated guidelines for mandatory physical service of notice under section 35(3).

D.K. Basu Guidelines

The D.K. Basu Guidelines on Arrest, Detention, and Interogation were Supreme Court of India in D.K. Basu v. State of West Bengal[8] has laid down 11 specific requirements and procedures that the police and other agencies have to follow for the arrest, detention and interrogation of any person. These requirements were issued to the Director General of Police and the Home Secretary of every State. They were obliged to circulate the requirements to every police station under their charge. Every police station in the country had to display these guidelines prominently. The judgment also encouraged that the requirements be broadcast through radio and television and pamphlets in local languages be distributed to spread awareness.

These guidelines are:

- Police arresting and interrogating suspects should wear “accurate, visible and clear” identification and name tags, and details of interrogating police officers should be recorded in a register.

- A memo of arrest must be prepared at the time of arrest. This should: Have the time and date of arrest. be attested by at least one witness who may either be a family member of the person arrested or a respectable person of the locality where the arrest was made. be counter-signed by the person arrested.

- The person arrested, detained or being interrogated has a right to have a relative, friend or well-wisher informed as soon as practicable, of the arrest and the place of detention or custody. If the person to be informed has signed the arrest memo as a witness this is not required.

- Where the friend or relative of the person arrested lives outside the district, the time and place of arrest and venue of custody must be notified by police within 8 to 12 hours after arrest. This should be done by a telegram through the District Legal Aid Authority and the concerned police station.

- The person arrested should be told of the right to have someone informed of the arrest, as soon as the arrest or detention is made.

- An entry must be made in the diary at the place of detention about the arrest, the name of the person informed and the name and particulars of the police officers in whose custody the person arrested is.

- The person being arrested can request a physical examination at the time of arrest. Minor and major injuries if any should be recorded. The "Inspection Memo" should be signed by the person arrested as well as the arresting police officer. A copy of this memo must be given to the person arrested.

- The person arrested must have a medical examination by a qualified doctor every 48 hours during detention. This should be done by a doctor who is on the panel, which must be constituted by the Director of Health Services of every State.

- Copies of all documents including the arrest memo have to be sent to the Area Magistrate (laqa Magistrate) for his record.

- The person arrested has a right to meet a lawyer during the interrogation, although not for the whole time.

- There should be a police control room in every District and State headquarters where information regarding the arrest and the place of custody of the person arrested must be sent by the arresting officer. This must be done within 12 hours of the arrest. The control room should prominently display the information on a notice board.

Guidelines on arrest of senior citizens in family matters

The Hon'ble High Court of Delhi dated in Shashi Kumar Mahajan Vs Commissioner of Police, Delhi,[9] a Committee of senior police officers was constituted for laying down guidelines for arrest of senior citizens in family matters. As per maintenance and welfare of Parents and Senior Citizens Act, 2007, a "Senior Citizen" is any person, being a citizen of India, who has attained the age of sixty years or above. The issue of arrest has come into focus since it is observed that in some matrimonial disputes, there are occasions when in addition to the allegation of demand of dowry or harassment, allegations of violence, molestation, rape and unnatural sex etc. are made against the extended family members and relatives, some of whom are senior citizens. The guiding principle is that the arrest of a senior citizen should not be done in a mechanical or routine manner. All the provisions of law, besides the guidelines of the Hon'bles Supreme Court and Delhi High Court, regarding arrest, must be followed meticulously and in true letter and spirit.

- The IO must tread cautiously and take due care in all such cases.

- The available evidence should be weighed properly before taking any coercive action against any such person, especially the senior citizen(s). If at all arrest is required, the IO shall satisfy himself of the desirability of the arrest, looking into aspects such as the person's age, health condition, his/her chances of escaping or evading the process of law etc.

- If there is sufficient evidence against the senior citizen and the IO is of the opinion that arrest is required, prior approval of the concerned DCP shall be taken before making arrest.

Arrest as defined in case laws.

Arrest is exception not rule

Joginder Kumar v. State of UP (1994)

In Joginder Kumar v. State of UP[10], the court held that ‘no arrest can be made because it is lawful for the police officer to do so. The existence of the power of arrest is one thing; the justification for its existence is another. The police officer must be able to justify the arrest apart from his power to do so.’ Arrest in cognizable cases may be considered justified in one or other of the following circumstances:

- The case involves a grave offence like murder, dacoity, robbery, rape etc. and it is necessary to arrest the suspect to prevent him from escaping or evading the process of law.

- The suspect is given to violent behaviour and is likely to commit further offences.

- The suspect requires to be prevented from destroying evidence or interfering with witnesses or warning other suspects who have not yet been arrested.

- The suspect is a habitual offender who, unless arrested, is likely to commit similar or further offences.

- Except in heinous offences, as mentioned above, an arrest must be avoided if a police officer issues notice to the person to attend the police station and not leave the station without permission.

- The power to arrest must be avoided where the offences are bailable unless there is a strong apprehension of the suspect absconding .

- Police officers carrying out an arrest or interrogation should bear clear identification and name tags with designations. The particulars of police personnel carrying out the arrest or interrogation should be recorded, in a register kept at the police station.

Arnesh Kumar v. State of Bihar (2016)

In Arnesh Kumar v. State of Bihar[11], the Supreme Court laid down the guidelines to stop the menace of unnecessary arrests. This ruling emphasized that arrests should be an exception, particularly in cases where the potential punishment is less than seven years of imprisonment. The guidelines provided in this judgement urged the police to assess the necessity of arrest under Section 41 of the Criminal Procedure Code. Ensuring adherence to Supreme Court principles is incumbent upon investigating officers. The guidelines were the Procedure when a police officer decides that arrest has to be made in an offense which is cognizable and punishable with imprisonment up to 7 years.

Procedure to be followed for issuance of notice/orders

Amandeep Singh Johar Vs Govt. of NCT of Delhi (2018)

In Amandeep Singh Johar Vs Govt. of NCT of Delhi, the Hon'ble High Court of Delhi, directed that as far as working of Section 41A is concerned,

- Police officers should be mandatorily required to issue notices under Section 41A Cr.P.C (in the prescribed format) formally to be served in the manner and in accordance with the terms of the provisions contained in Chapter-VI of the Criminal Procedure Code. Model form of notice under 41A Cr.P.C and his acknowledgement is enclosed herewith as Annexure-A.

- The concerned suspect or accused person will necessarily comply with the terms of the notice under section 41A Cr.P.C and make himself available at the requisite time and place.

- If the accused is unable to present himself at the given time for any valid and justifiable reason.,the accused should in writing immediately, intimate the investigating officer and seek an alternative time within a reasonable period, which should ideally not exceed a period of firer working days, from the date on which he were required to attend, unless he is unable to show justifiable cause for such non- attendance.

- Unless it is detrimental to the investigation, the police officer may permit such rescheduling, however, only for justifiable causes to be recorded in the Case Diary. Should the Investigating Officer believe that such extension is being sought to to cause delay to the Investigation or the suspect or accused person is being evasive by seeking time, (subject to intimation to the O/C Police Station/SDPO of the concerned Police Station), deny such request and mandatorily require the said person to attend.

- A suspect or accused on formally receiving a notice under section 41A Cr.P.C and appearing before the concerned officer for investigation or interrogation at the police station, may request the concerned 10 for an acknowledgement.

- In the event the suspect or accused is directed to appear at a place other than the police station (sa envisaged under Section 41A (1) Cr.P.C), the suspect will be at liberty to get the acknowledgement receipt attested by an independent witness if available at the spot in addition to getting the same attested by the concerned investigating officer himself.

- A duly indexed booklet containing serially numbered notices in triplicate carbon copy format should be issued by the O/C of the Police Station to the Investigating Officer. The Notice should necessarily contain the following details:

- Serial Number

- Case Number

- Date and time of appearance

- Consequences in the event of failure to comply

- Acknowledgement slip

- The Investigating Officer shall follow the following procedure

- The original is served on the accused suspect

- A carbon copy (on white paper) is mained by the 10 in his or her case diary, which can be shared to to the concerned Magistrate as and when required,

- Used booklets are to be deposited by the 10 with the OC of the Police Station who shall win the The completion of the investigation and submission of the final report under section 173 of the CrPC

- The Police department shall frame appropriate rules for the preservation and destruction of such booklets.

Satender Kumar Antil v. Central Bureau of Investigation &Anr. (2022)

In Satender Kumar Antil v. Central Bureau of Investigation &Anr.[12] while interpreting Section 41(1)(b)(i) and (ii) inter alia holding that notwithstanding the existence of a reason to believe qua a police officer, the satisfaction for the need to arrest shall also be present. Thus, sub-clause (l)(b)(i) of Section 41 has to be read along with sub-clause (ii) and therefore both the elements of 'reason to believe' and ‘satisfaction qua an arrest’ are mandated and accordingly are to be recorded by the police officer.

The Supreme Court reiterated that Magistrates must demand justification from the prosecution, especially where statutory safeguards such as Section 41A are ignored. Thus, prima facie scrutiny is the threshold test:

- Has the police complied with Section 41A/35 BNSS safeguards?

- Does the material placed on record disclose a reasonable connection between the accused and the alleged crime?

If either test fails, custody must be refused.

Grounds of Arrest

Prabir Purkayastha v. State (NCT of Delhi) (2024)

In Prabir Purkayastha v. State (NCT of Delhi), the Supreme Court, distinguished between the 'reasons for arrest' and 'grounds of arrest' and further held that there was a significant difference between the two. It explained that 'reasons of arrest' are formal and could apply generally to any person arrested of an offence. Meanwhile,'grounds of arrest' are personal and specific to the person arrested. Further, The Court had insisted that written grounds be furnished under special statutes like the PMLA and UAPA - but left ambiguous whether the same protection extended to ordinary offences.

Mihir Rajesh Shah vs The State Of Maharashtra (2025)

In Mihir Rajesh Shah vs The State Of Maharashtra[13] the Supreme Court held that grounds of arrest must be communicated in writing to every arrested person, in a language they understand, irrespective of the nature of the offense or the statute under which the arrest is made. This includes all offenses under the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023 (BNS), formerly the Indian Penal Code, 1860 (IPC), as well as special statutes. The judgment establishes a strict timeline requiring that written grounds must be furnished to the arrestee within a reasonable time and, in any case, at least two hours prior to production before a Magistrate for remand proceedings. This two-hour rule does not emerge from legislation but from constitutional reasoning. The Court described it as a “judicious balance between safeguarding the arrestee’s constitutional rights under Article 22(1) and preserving the operational continuity of criminal investigations.”

Further, the Court declared that non-compliance with these requirements renders both the arrest and subsequent remand illegal, entitling the arrested person to immediate release. This landmark decision extends the principles previously established in cases involving special statutes like the Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002 (PMLA) and the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967 (UAPA) to all criminal arrests, thereby creating a uniform national standard for protecting personal liberty at the point of arrest.

Arrest as defined in International Instruments

International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance

International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance passed by the UN in 2010 in order to prevent enforced disappearance of people and prevent arrest, detention, abduction or any other form of deprivation of liberty by agents of the State or by persons or groups of persons acting with the authorization, support or acquiescence of the State, followed by a refusal to acknowledge the deprivation of liberty or by concealment of the fate or whereabouts of the disappeared person, which place such a person outside the protection of the law.

Body of Principles for the Protection of All Persons under Any Form of Detention or Imprisonment

The "Body of Principles for the Protection of All Persons under Any Form of Detention or Imprisonment[14]" is a set of United Nations guidelines adopted by General Assembly resolution 43/173 in 1988. It establishes standards to ensure the humane treatment and protection of the human rights of all persons deprived of their liberty, whether they are detained (not yet convicted) or imprisoned (convicted). The principles define key terms such as "arrest," "detained person," and "imprisoned person," and emphasize treatment with humanity and respect for inherent dignity. They require that detention or imprisonment be ordered or controlled by judicial or competent authority, and articulate rights to legal counsel, prompt information about charges, communication with family, protection against torture or cruel treatment, and access to prompt judicial review of the lawfulness of detention. The principles forbid torture and inhumane or degrading treatment under any circumstances and mandate procedural safeguards, impartial investigations of violations, and rights to fair disciplinary hearings for detainees. They apply universally, prohibiting discrimination based on race, sex, religion, or other status, and stress the presumption of innocence for those not yet convicted. The principles serve as an authoritative framework guiding states and authorities on humane detention laws and practices to uphold fundamental human rights protections.

International Experience

United Kingdom

In the UK, the Police and Criminal Evidence Act (PACE Act 1984) and Criminal Justice Act 2003 specify the rights of the arrested person. Moreover, through various court decisions, the scope and concept of safeguards are also established. The key assurance is that the arrested person is Informed about the reason for arrest by the arresting police officer.

Section 28(1) of the PACE Act states that where a person is arrested, the arrest is not lawful unless the person arrested is informed that he is under arrest as soon as it is practicable after his arrest. It is the right of the arrested person to know the grounds for being arrested and it is the legal duty of the police to inform the person that he is under arrest and grounds for his arrest.[15]

Technological Transformation

Arrested Person List (State CCTNS)

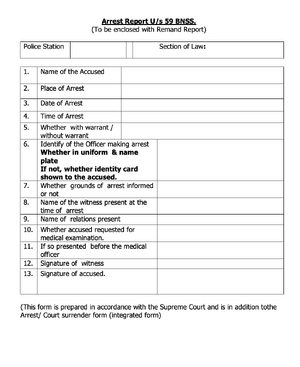

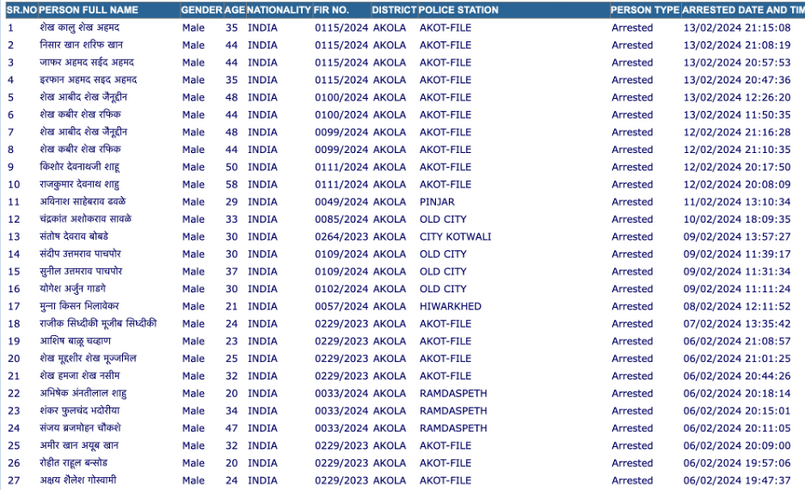

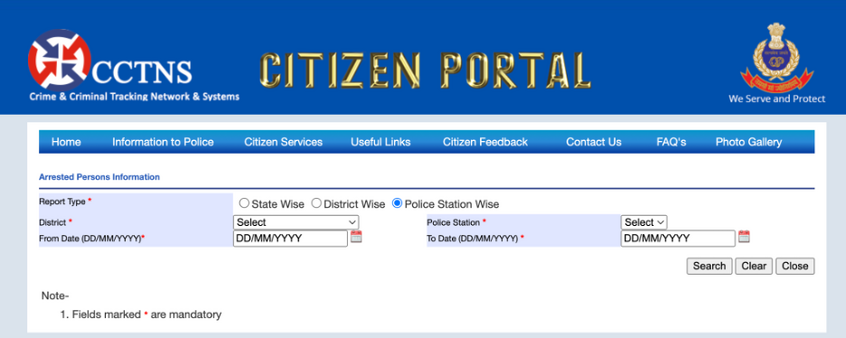

Crime and Criminal Tracking Network and Systems (CCTNS) was a project started in 2009 to provide for greater transparency in the policing system. Every state has a CCTNS portal wherein information relating to FIR status, missing persons, etc can be found. The data on arrested persons can be accessed online for certain States, as provided below. To conduct a search for an arrested person, the required information includes name of person, district where arrest was made, date range of arrest, police station etc.

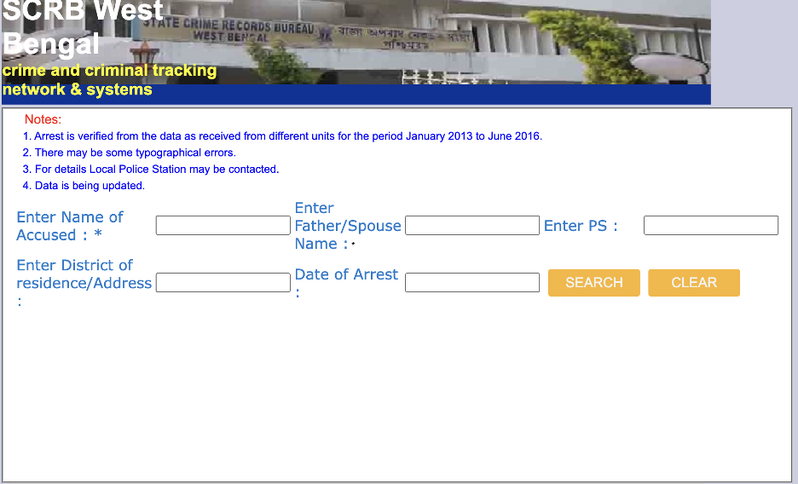

The CCTNS Portal of West Bengal mandatorily requires the name of the arrested person along with the name of their spouse. On the other hand, Gujarat merely requires a user registration and the search filter requires the date range of arrest and Tamil Nadu requires registration through OTP and allowing the user to make 10 searches with a single OTP.

Thus, there is state based variation over the data provided relating to the arrested person on account of whether user registration is required, Search filtering, and data fields related to information related to arrest and arrested person.

Once such search is made, the data relating to the arrested person may be accessed.

In terms of details related to arrestee and crime details, Kerala provides a comprehensive data on arrested person. On the other hand, the Chattisgarh CCTNS portal does not provide the address of the arrested person and the father’s name. The sex and age is also not provided. Likewise, the Maharashtra portal does not provide the name of father, but provides for the gender, sex as well as the nationality of the arrested person.

Kerala

Chattisgarh

Gujarat

Maharashtra

Madhya Pradesh

Odisha

Tamil Nadu

West Bengal

Appearance of Arrest in Official Databases

Crime in India (NCRB)

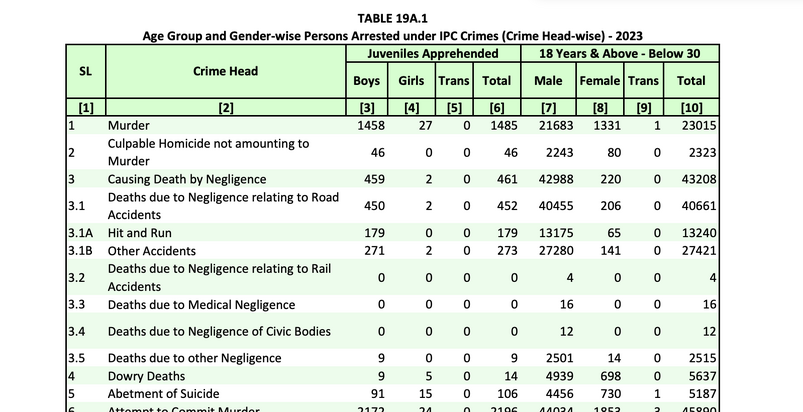

Chapter 19, Volume III of the Crime in India report 2023, collected data including the number of persons arrested, their demographic profiles, the offenses for which they were arrested, and the legal outcomes such as chargesheets, convictions, and bail status. The report synthesizes this data to provide insights on arrest trends, highlighting regional variations, crime categories, and patterns over time.

Research that engages with Arrest

Transparency of Information about Arrests and Detentions Implementation of Section 41C of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (CHRI 2016)

The Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative (CHRI) conducted a comprehensive study titled Transparency of information about arrests and detentions: Implementation of Section 41C of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973—A scoping study of compliance across 23 states and the UT of Delhi[16]on the implementation of Section 41C of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC), 1973, which mandates police transparency about arrests across 23 Indian states and the Union Territory of Delhi. The study employed a two-phase methodology involving surveys, Right to Information (RTI) requests, and analysis of police practices and data disclosure. The key findings reveal that most police departments have failed to comply with Section 41C’s requirements, such as maintaining and publicly sharing arrest databases. Only a few states like Kerala and Bihar issued detailed operational guidelines and partially complied by displaying arrest information online and at Police Control Rooms. Many others lacked clear policies, adequate infrastructure, or budgets to support transparency, with widespread confusion over responsibility and ineffective communication channels between police stations and higher police authorities. The study highlights critical barriers, including poor implementation of Supreme Court directives, absence of uniform procedures, and insufficient technology use, which collectively hinder public access to arrest information. CHRI recommends systemic reforms including clear standard operating procedures, training for police personnel, digitization and regular publication of arrest data, budgetary support, and accountability mechanisms to fulfill the transparency mandate and protect citizens’ rights during arrest and detention processes. This research sheds light on institutional apathy and underscores the urgent need for reforms to ensure lawful policing and enhance public oversight

Status of Policing in India Report (SPIR) 2023: Surveillance & the Question of Privacy (Common Cause and CSDS)

The SPIR 2023: Surveillance & the Question of Privacy [17] The question of surveillance and privacy has been dealt with by highlighting surveillance practices adopted by the State such as CCTV monitoring, internet tracking etc. The findings with respect to CCTV shows that there is arguably no significant reduction in commission of cognizable offences resulting from installation of cameras, although the cameras prove useful for detection of offenders post the offence has been committed. It further highlights that of all the cybercrime cases reported, most of them are under Section 65D of the IT Act, relating to impersonation. The data over arrest shows high variation between chargesheeting and conviction rate of different states. For instance, per the NCBR data of 2021, of the 6887 persons arrested in UP, 45.5% were chargesheeted and 83.2% were convicted. In contrast, 1395 people were arrested in Gujarat, of which 58.4 % were chargesheeted, however no one was convicted.

Status of Policing in India Report (SPIR) 2021: Policing in Conflict Affected Region[18]

The SPIR 2021: Policing in conflict affected region[19] highlights police violence in states affected by conflict such as naxalism. A survey conducted in these states indicate that personnel and common people showed considerable support for the violent behavior of the police when against ‘protagonists of political violence’, ie, the naxalites and insurgents. On the other hand, there was a divide over personnel and common people over preventive detentions and other precautionary measures, with the personnel showing greater inclination towards the same. However, concerning the arrest of naxalite sympathizers and use of drone cameras for surveillance, there was again a shared agreement. Moreover, common people hold the perception that certain groups such as the poor and STs are more likely to be targeted by the police for naxalism charges. People in regions of Left Wing Extremism repose ‘higher trust in police than in insurgent regions’.

Arrest Discretion Behaviour of the Police in India: A Socio-Legal Study

The 2009 criminal law amendment sought to reduce the number of arrests made, however, the data shows negligible reduction in the 5 years post 2009.[20] This study highlights various factors influencing arrests, and categorizes them as organizational, situational, subcultural, environmental and individual. An interplay of legal and extra legal factors such as, for instance, the personal character of the officer, a belief that the criminal system is ineffectual and arrest is the only punishment, etc ‘create a complex maze in which the arrest decision behavior is processed and ultimately taken’.

Counter Mapping Pandemic Policing: A Study of Sanctioned Violence in Madhya Pradesh (CPAP)

This report[21] attempts to profile the arrests made during the pandemic and establish the existence of a ‘structural attitudes’ of policing which leads to marginalization. While no ‘direct evidence of discrimination’ is provided, the report raises the concern that criminalisation has deep effects over the economic status and well being of the families. This requires stringent constitutional safeguards and legislative reforms to curb the excessive power available to the state machinery. The report concludes by presenting recommendations such as decentering focus on prisons, moving towards decarceration and decriminalization, disaggregating data for arrested persons, and changing the culture of policing for low level offenses.

Status of Policing Report: Police Torture and (Un)Accountability 2025

SPIR report, published by Common Cause and Lokniti – Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS), brings crucial findings regarding arrest and procedures. The report analyses the responses from 8,276 police personnel of various ranks, across 17 states and UTs, along with judges, lawyers and doctors were interviewed to obtain a holistic understanding. According to the report, 41 percent police personnel said that arrest procedures are “always” adhered to, while 24 percent said that they are “rarely or never” adhered to. Kerala reported the highest compliance with arrest procedures. The report also shows that police personnel believe that lawyers should not be present during interrogation.

Challenges and Way Ahead

Several constitutional provisions and legal requirements safeguard the rights of the arrested individuals. Article 22[22] of the Indian Constitution emphasizes the right to be informed about the reason for arrest, consult a legal practitioner, and not be detained without being informed of the grounds for arrest. The following aspects illuminate the significance and nuances of the right to legal representation:

Right to Legal Representation

The Supreme Court has affirmed the right of an accused to consult a legal practitioner under Article 21 [22]of the Constitution. This includes the right to effective legal representation, ensuring compliance with mandatory procedural requirements.

Procedural Mandates

Article 22(1)[22] and constitutional principles were reinforced in the seminal case of DK Basu v. Union of India[23]. The Supreme Court emphasized not only the right of the arrested person to be informed of the grounds of arrest but also their right to consult a legal practitioner. This procedural requirement ensures that individuals are not only aware of the charges against them but are also equipped with the means to navigate the legal complexities of their situation.

Magisterial Inquiry and Legal Aid

In the case of Gautam Navlakha v. State (NCT of Delhi)[24], the Delhi High Court emphasized the necessity of a magisterial inquiry into whether the arrested person was informed about the grounds of arrest and whether they desired legal representation. The court rejected the mere cosmetic presence of a legal aid lawyer and stressed the importance of effective representation.

Related Terms

Confinement

Generally, custody is a larger set of which arrest is a small subset, and there can be custody without arrest but not arrest without custody. Thus, for example, in Niranjan Singh, Justice Krishna Iyer observed that ‘an accused can be in custody not merely when the police arrests him’.This is because a person can be in custody by submitting to the Court as well.

Arrest in Civil Law

A decree is passed by the court under the Code of Civil Procedure (hereinafter referred to as CPC) to decide the rights and liabilities of the persons in a matter of controversy. The person in whose favour a decree is passed is called decree-holder and against whom the decree is passed is judgement debtor. There are various ways under civil law by which a decree can be passed. One such way is “arrest and detention”.[25]

This is covered in S.51 of the CPC which states that such a decree can be enforced while the mode of execution of a decree for arrest and detention is listed under Order XXI.

Custody in Remand and Pre- Remand

Police custody of an accused person if the investigation is not completed within 24 hours is called Remand. In remand to police custody the accused is in the physical custody of the police and is normally lodged in the lock up of the police station or lock up of any other investigating agency.In judicial custody the accused remains under the custody of the magistrate and is normally incarcerated in jail.[26]

“Custody in pre-remand" is essentially jailed while waiting for their first court hearing. The court will then decide if there are enough reasons to keep them detained (remanded) until trial, or if they can be released on bail.

Custody

While the terms 'arrest' and 'custody' are often used interchangeably, a crucial legal distinction exists. An arrested person holds the right to seek bail, unlike someone under custody, who may not necessarily have such right. This distinction applies to specific contexts, for instance Sections 107 and 108 of the Customs Act. Therein, summons in respect of an enquiry may amount to custody but not to arrest, and such custody could subsequently materialize into arrest.

While the terms 'arrest' and 'custody' are often used interchangeably, a crucial legal distinction exists. An arrested person holds the right to seek bail, unlike someone under custody, who may not necessarily have such right. This distinction applies to specific contexts, for instance Sections 107 and 108 of the Customs Act. Therein, summons in respect of an enquiry may amount to custody but not to arrest, and such custody could subsequently materialize into arrest.

While the terms 'arrest' and 'custody' are often used interchangeably, a crucial legal distinction exists. An arrested person holds the right to seek bail, unlike someone under custody, who may not necessarily have such right. This distinction applies to specific contexts, for instance Sections 107 and 108 of the Customs Act. Therein, summons in respect of an enquiry may amount to custody but not to arrest, and such custody could subsequently materialize into arrest.

House Arrest

Section 167(2) allows the Magistrate to ‘authorise the detention of the accused in such custody as such Magistrate thinks fit’. This includes House Arrest, which, while not defined in the CrPC, has been understood as a form of Custody which curtails the liberty of an individual, as held in Gautam Navlakha. A court may order for house arrest based on the facts of each case. Relevant considerations to be taken are include ‘age, health condition and the antecedents of the accused, the nature of the crime, the need for other forms of custody and the ability to enforce the terms of the house arrest’, per Gautam Navlakha judgement.

References

- ↑ BLACK'S LAW DICTIONARY, 4th Edn (revised) 1968 page. 140 available at https://www.latestlaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Blacks-Law-Dictionery.pdf

- ↑ Information of arrested persons Rules, 2024

- ↑ Information of Arrested Persons Rules, 2025

- ↑ https://blog.ipleaders.in/all-about-juvenile-justice-act/#Recent_amendments_in_the_Juvenile_Justice_Act_Bill_2015_passed_by_the_Lok_Sabha

- ↑ https://police.assam.gov.in/sites/default/files/swf_utility_folder/departments/assampolice_webcomindia_org_oid_8/menu/document/order_english.pdf

- ↑ Imphal, 12th October, 2024. STANDING ORDER NO. 195/2024; OFFICE OF THE DIRECTOR GENERAL OF POLICE, MANIPUR https://bprd.nic.in/uploads/table_c/Section%20of%20BNSS%2035.pdf

- ↑ STANDING ORDER NO. 330/2019; Delhi Police

- ↑ AIR 1997 SC 610

- ↑ WP(Crl) No. 503/2018 dated 10.09.2018

- ↑ Joginder Kumar vs State Of U.P on 25 April, 1994 1994 SCC (4) 260

- ↑ (2014) 8 SCC 273

- ↑ Satender Kumar Antil v. Central Bureau of Investigation &Anr (2021) 10 SCC 773

- ↑ Mihir Rajesh Shah vs The State Of Maharashtra 2025 INSC 1288

- ↑ General Assembly resolution 43/173 available at: https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/body-principles-protection-all-persons-under-any-form-detention

- ↑ https://journals.iium.edu.my/iiumlj/index.php/iiumlj/article/view/645/333

- ↑ Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative. (2016). Transparency of information about arrests and detentions: Implementation of Section 41C of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973—A scoping study of compliance across 23 states and the UT of Delhi. Retrieved from https://www.humanrightsinitiative.org/download/1466587392Section41C-Study-Report-22-01-16.pdf

- ↑ Common Cause and Centre for the Study of Developing Societies. (2023). Status of Policing in India Report 2023. Retrieved fromhttps://www.commoncause.in/wotadmin/upload/REPORT_2023.pdf

- ↑ https://www.commoncause.in/uploadimage/page/SPIR-2020-2021-Vol%20I.pdf

- ↑ Common Cause & Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS). (2021). Status of Policing in India Report 2020-2021, Volume I: Policing in Conflict-Affected Regions. Common Cause and CSDS. Retrieved from https://www.commoncause.in/uploadimage/page/SPIR-2020-2021-Vol%20I.pdf

- ↑ https://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in:8443/jspui/handle/10603/331564

- ↑ https://cpaproject.in/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Countermapping-Pandemic-Policing-CPAProject.pdf

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 https://cdnbbsr.s3waas.gov.in/s380537a945c7aaa788ccfcdf1b99b5d8f/uploads/2023/05/2023050195.pdf

- ↑ https://indiankanoon.org/doc/501198/

- ↑ https://indiankanoon.org/doc/199736728/

- ↑ https://blog.ipleaders.in/arrest-and-detention/

- ↑ https://www.legalserviceindia.com/legal/article-12873-remand-to-police-custody.html#:~:text=In%20remand%20to%20police%20custody,is%20normally%20incarcerated%20in%20jail.