Bail

What is Bail?

Bail is derived from the old French verb “baillier” meaning to ‘give or deliver’. According to Black’s Law Dictionary, what is contemplated by bail is to “procure the release of a person from legal custody, by undertaking that he shall appear at the time and place designated and submit himself to the jurisdiction and judgment of the court."[1] According to Halsbury’s Laws of England: "the effect of granting bail is not to set the defendant (accused) free, but to release him from the custody of law and to entrust him to the custody of his sureties who are bound to produce him to appear at his trial at a specified time and place. The sureties may seize their principal at any time and may discharge themselves by handing him over to the custody of the law and he will then be imprisoned."[2]

Bail also refers to the security furnished by the accused for their release during the pendency of trial or investigation. The person receiving the bail has to ensure his/her availability at the required time before the legal authority. The law lexicon defines bail as the security for the accused person's appearance on which he is released pending trial or investigation. What is contemplated by bail is to "procure the release of a person from legal custody, by undertaking that he/she shall appear at the time and place designated and submit him/herself to the jurisdiction and judgment of the court”.

Wharton’s Law Lexicon defines bail as “to set at liberty a person arrested or imprisoned, on security being taken for his appearance on a day and at a place certain, which security is called bail because the party arrested or imprisoned is delivered into the hands of those who bind themselves or become bail for his due appearance when required, in order that he may be safely protected from prison, to which they have if they fear his escape, etc., the legal power to deliver him."[3]

Official Definition of Bail

Bail as defined in Legislations

1. Bharatiya Nagrik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS)

Bail has been defined in the Bharatiya Nagrik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023 (BNSS) in Section 2(1)(b) as “release of a person accused of or suspected of commission of an offence from the custody of law upon certain conditions imposed by an officer or Court on execution by such person of a bond or a bail bond”.

The BNSS further defines Bond as 'a personal bond or an undertaking for release without surety’ [S.2(1)(e)] and Bail Bond as ‘an undertaking for release with surety' [S.2(1)(d)]. A combined reading of these definitions makes apparent the two ways by which a person may be released on bail i.e. execution of a bond (without surety) or a bail bond (with payment of surety).

2. Code of Criminal Procedure (Cr.P.C.) [Repealed]

Bail is not specifically defined in the Cr.P.C. However, the conditions for availing the bail, including other provisions, are available in the Code. The Code of Criminal Procedure uses the term bail to include release either with or without surety.

Further, The Cr.P.C. classifies offences as bailable and non-bailable.

- For bailable offences, bail is a matter of right granted as soon as the accused is willing to furnish bail under S. 436 of Cr.P.C. and the offences herein are less serious.

- Non-bailable offences are more serious in nature and while the bail can be granted here too, it is not a matter of right in this case.

Legal Provisions relating to Bail

Types of Bail

There is no statutory classification of bail. However, bail may be categorized into five types based on the conditions of the grant of bail. It includes regular bail (conditioned on the basis of bailable and non-bailable offences), anticipatory bail, default bail, interim bail and bail after conviction.

Regular Bail

According to Section 478(1) of BNSS (436 of Cr.P.C.), if the offence alleged is bailable, then, the Accused is entitled for Bail as a matter of right, may be before Police station itself, or if forwarded to Magistrates Court, before Magistrates court. The court imposes a statutory duty on the police officer to grant bail upon request. In bailable offences bail is a right and not a favor. In such offences there is no question of any discretion in granting bail. Additionally, Section 479(1), BNSS stipulates the maximum period of detention for an undertrial prisoner is defined, stating that if the accused has been detained for a duration equivalent to 50% of the maximum imprisonment term for the offence during the investigation, they shall be released by the court upon executing a bond, with or without sureties.

The provisions of Section 480 of BNSS (437 of Cr.P.C) empowers two authorities to consider the question of bail, namely (1) a court and (2) an officer-in-charge of the police station who has arrested or detained without warrant, a person accused or suspected of the commission of a non-bailable offence. Although this section deals with the power or discretion of a court as well as a police officer in charge of police station to grant bail in non- bailable offences it has also laid down certain restrictions on the power of a police officer to grant bail and certain rights of an accused person to obtain bail when he is being tried by a Magistrate. Formerly, Section 437, Cr.P.C. dealt with the powers of the trial court and the Magistrate (to whom the offender is produced by the police or the accused surrenders or appears) to grant or refuse bail to person accused of, or suspected of the commission of any non-bailable offence. In such a case, the grant of bail is discretionary and it can be availed only if a strong case is presented. This includes specific grounds, including if:

- The accused is below or at 16 years of age.

- The accused is a woman.

- The accused is ill or infirm. For habitual offenders, bail is granted only under special circumstances.

Under the corresponding Section 480 of BNSS, the age is increased from sixteen to eighteen. This amendment makes the provision consistent with the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015.

Anticipatory Bail

As per Section 482 of BNSS (438 of Cr.P.C.), the person anticipating arrest for a non-bailable offence (where bail cannot be sought as a matter of right) may apply to the High Court or Sessions Court for a grant of bail against such arrest. Section 482 of the BNSS has excluded certain aspects that were specified in Section 438 of Cr.P.C, including the four factors the Court was to take into consideration while granting bail. The current law rests discretion upon judges such that they may release the accused on bail as they deem fit. The exclusion also spanned the following-

- Giving the Public Prosecutor a reasonable opportunity to be heard" during the application hearing [S. 438(1-A), Cr.P.C.]

- Ensuring the presence of the applicant seeking anticipatory bail [S. 438(1-B), Cr.P.C.]

The BNSS does not provide any express criteria for determining the grounds for granting anticipatory bail, which results in giving the court absolute discretion without any specified guidelines to be followed.

Know more: Anticipatory Bail

Default Bail

As per Section 187 of BNSS, the magistrate may stipulate a maximum period for the detention of the accused in cases where it appears that the investigation cannot be completed within 24 hours and the accused is entitled to default bail on the completion of the maximum period.

While Section 167 of Cr.P.C. did not provide for the option to request custody in parts, Section 187 of the BNSS has added that the maximum duration for seeking police custody is 15 days, and can be undertaken in whole or in parts. Further, It grants police the authority to request custody either in a single stretch or in parts throughout the initial 40 or 60 days of the total detention period of 60 or 90 days respectively, as may be applicable.

Additionally, to safeguard the accused’s right to bail, Section 480 of the BNSS provides that the mere fact that an accused person may be required to be identified by witnesses during the investigation or for police custody beyond the first fifteen days shall not be sufficient ground for refusing to grant bail if he is otherwise entitled to be released on bail.

Interim Bail

Interim bail is granted temporarily for a short term during the pendency of regular or anticipatory bail. There is no express legal provision for ad-interim or interim bail but the court has the discretion to grant it. Section 483 of BNSS (Section 439, Cr.P.C.) is on the High Court’s & Supreme Court’s power to release the accused on bail in custody.

Previously, Section 438, Cr.P.C. expressly provided for interim bail pending disposal of the plea for anticipatory bail, as against its current modification under Section 482 of BNS. This was an effective check against unscrupulous exercise of the arrest power by the police for interim bail may be granted when the court is satisfied that the object of the accusation against accused is to injure his reputation and humiliate him. This was consistent with the concept of fundamental right to life and liberty under Article 21 of the Constitution of India.

Bail after conviction

Section 430 of BNSS (Section 389 of Cr.P.C.) deals with a situation where convicted person can get a bail from appellate court after filing the criminal appeal. Section 430 (3) deals with a situation where the trial court itself can grant a bail to convicted accused enabling him to prefer an appeal.

Grant of Bail: Factors to be taken into Consideration

In the case of the State of Maharashtra v. Sitaram Popat Vital[4], the court gave factors to be taken into consideration to decide on the grant of bail. They include:

- The nature of the accusation and the severity of punishment in case of conviction and the nature of supporting evidence;

- Reasonable apprehension of tampering of the witness or apprehension of threat to the complainant;

- Prima facie satisfaction of the Court in support of the charge.

In Satender Kumar Antil v. CBI & Anr.[5], where the Supreme Court categorized the offences into four categories and gave specific guidelines for each along with general conditions to co-exist for the applicability of said guidelines.[6]

| Nature of Offence | Conditions | Course to be adopted by courts |

|---|---|---|

| Offences punishable with 7 years or less | 1) Accused not arrested during interrogation.

2) Cooperated throughout the investigation including appearance before Investigating Officer whenever called. |

1) Summon (Appearance through lawyer permissible)

2) Bailable warrant

|

| Offences punishable with death, imprisonment for life, 7 years or more | On appearence of accused in court pursuant to process issued; bail application to be decided on merits | |

| Special Acts containing stringent provision for bail |

The Supreme Court in In Re Policy Strategy for Grant of Bail v. Mr Gaurav Agrawal[8] gave 7 directions with respect to the execution of bail orders that include relaxations in the condition of producing surety, adequate notice of grant of bail to the prisoner, engagement of District Legal Services Authority in case of non-execution of orders of bail, etc.

Furthermore, the case of Munnesh vs State of Uttar Pradesh, 2025 [9] mandates the disclosure of criminal antecedents in all bail-related Special Leave Petitions. The Supreme Court, hence, directed that each individual approaching the Court with a SLP (Criminal) challenging orders passed by the high courts/sessions courts declining prayers under Sections 438/439 of the Cr.P.C. or under Sections 482/483, BNSS shall mandatorily disclose in the synopsis his criminal antecedents i.e. that either he is a man of clean antecedents or if he has knowledge of his involvement in any criminal case and if found incorrect subsequently, serves as a ground for dismissal of the petition.

Cancellation of Bail

There is no specific provision pertaining to cancellation of bail but Section 480(5) of BNSS (437(5) of Cr.P.C.) empowers the court of Magistrate to cancel the bail and order the arrest of such person for the non-bailable offence. The bail can also be cancelled by the Session Court or the High Court under Section 483(3) of BNSS (439(2) of the Cr.P.C.).

The Cr.P.C. does not enumerate the conditions for the cancellation of bail but various judgements declare grounds for the cancellation of Bail. The Supreme Court, in the case of Dolat Ram v. State of Haryana[10] held that bail once granted should not be cancelled in a mechanical manner without considering whether any supervening circumstances have rendered it no longer conducive to a fair trial to allow the accused the concession of bail. It was observed that very cogent and overwhelming circumstances were necessary for cancelling a bail that has already been granted. The judgement laid down several grounds for such cancellation of bail, also summarized in the case of Deepak Yadav v. State of U.P.[11], laid as follows:

(i) interference or attempt to interfere with the due course of administration of justice;

(ii) evasion or attempt to evade the due course of justice;

(iii) abuse of the concession granted to the accused in any manner;

(iv) possibility of the accused absconding;

(v) likelihood of/ actual misuse of the bail; and

(vi) likelihood of the accused tampering with the evidence or threatening witnesses.

Conditional Bail

Granting bail involves a delicate balance for a court. The accused is presumed innocent until proven guilty; thus, their liberty cannot be indefinitely curtailed. At the same time, the victim awaits justice and is entitled to a thorough investigation and fair trial, which requires the accused's participation. Therefore, courts often supervise bail releases by imposing certain conditions to maintain this balance.

This type of bail is granted contingent on certain conditions listed by the Court. It may include not leaving the particular jurisdiction without permission of the concerned authority, submission of passport, surety amount etc. The failure of these conditions may lead to the cancellation of bail. As per Section 480(3) of BNSS (437(3) of Cr.P.C.) and 482(3) of BNSS (438(2 )of the Cr.P.C.), the court is given the power to impose such conditions as it may deem necessary in the interest of justice apart from the reasons to ensure the attendance of the accused when required, protect witnesses from tampering or intimidation and to prevent the commission of similar offence.

The Supreme Court has time and again cautioned the lower courts that such conditions cannot be arbitrary.

- The scope of the concept of “interest of justice” in Section 437(3) of the CrPC has been considered by this Court in the case of Kunal Kumar Tiwari v. State of Bihar[12]. It was held that such conditions cannot be arbitrary, fanciful or extend beyond the ends of the provision and that "The phrase “interest of justice” as used under the clause (c) of Section 437(3) means “good administration of justice” or “advancing the trial process” and inclusion of broader meaning should be shunned because of purposive interpretation.”

- In the case of Munish Bhasin v. The State[13], the SC has held that the Court while granting bail should give due regard to the facts and circumstances of the case and can impose necessary, just and efficacious conditions.

- Absurd conditions like rakhi tying by the Madhya Pradesh HC were set aside by the SC in Aparna Bhat v. State of M.P.[14] holding that the bail conditions and orders should avoid reflecting stereotypical or patriarchal notions about women and their place in society, and must strictly be in accordance with the requirements of the Cr. PC.

- In State of A.P. v. Challa Ramkrishna Reddy[15], it was held that The conditions incorporated in the order granting bail must be within the four corners of Section 437(3). The bail conditions must be consistent with the object of imposing conditions. While imposing bail conditions, the Constitutional rights of an accused, who is ordered to be released on bail, can be curtailed only to the minimum extent required. Even an accused convicted by a competent Court and undergoing a sentence in prison is not deprived of all his rights guaranteed by Article 21 of the Constitution.

- In Frank Vitus v. Narcotics Control Bureau & Ors.[16] The Supreme Court struck down the condition requiring the accused to drop a Google Maps PIN for location tracking. This was deemed an infringement of the right to privacy. The ruling emphasized that bail conditions cannot impose continuous surveillance or result in a "virtual custody" of the accused.

Bail Bond and Surety Bond

The Cr.P.C. uses the term bail bond multiple times in sections 437A (Bail to require the accused to appear before the next appellate Court) and 446A (Cancellation of Bond and Bail Bond) but it does not define the same. Provisions have been made under Cr.P.C. regarding the form of a bond, amount of bond, conditions and execution of bond, sufficiency of sureties and discharge of sureties, procedures in case of insolvency or death of surety, etc.

Bail Bond is understood as a form of security to be deposited during the grant of bail to ensure the presence of the accused when required by the court which is refundable. However, if the accused disregards the conditions of bail, the right to refund is forfeited. Section 2(1)(d) of BNSS has defined "bail bond" as an undertaking for release with surety

Surety Bond: The grant of bail herein involves a relative or a friend of the accused who acts as surety to ensure the presence of the accused when called upon by the court. In case the accused does not fulfil the conditions of bail, the surety is liable to pay instead of the accused. It forms a part of the bail bond where another person furnishes the bail amount instead of the accused himself.

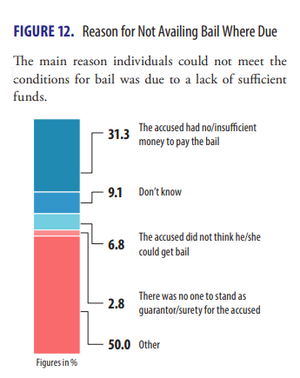

In In Re Policy Strategy for Grant of Bail SMW (Crl.) No. 4/2021, the SC noted the issue of non-release of undertrials even if they are granted bail because they are unable to furnish bail bonds. In lieu of the said problem, Court issued various directions. One of the notable directions is that if the bail bonds are not furnished within one month from the date of grant bail, the concerned Court may suo moto take up the case and consider whether the conditions of bail require modification/ relaxation.

Bail as defined in Official Government Reports

268th Law Commission Report

Further, the corrigendum to the 268th Report of Law Commission of India on Amendments to Criminal Procedure Code, 1973 which includes The Code of Criminal Procedure (Amendment) Bill, 2017 recommends a definition for ‘bail’:

“bail” primarily means the judicial interim release of a person suspected of a crime or any person accused of an offence held in custody, upon a guarantee that the suspect or the accused, as the case may be, will appear to answer the charges at some later date; and includes grant of bail to a person suspected of a crime or any accused person by a court/police officer/ officer authorised by law for the time being in force; and the guarantee may include release without any condition, release on condition of furnishing security in the nature of a bond, with or without sureties, or release on condition of furnishing other forms of security, or release based on any other condition, as deemed sufficient by the court/police officer/ officer authorised by law for the time being in force.

Bail as defined in Case Laws

Sunil Fulchand Shah v. Union of India [2000]

In Sunil Fulchand Shah v. Union of India[17], the court interpreted the term "bail" in its literal sense to mean "surety." The judgment clarified that bail refers to the release from custody, which can be either on personal bond or with sureties. This view underscores that bail is fundamentally premised on a monetary assurance —either one’s own assurance (also called personal bond / recognizance) or through third party sureties. The Supreme Court has also reiterated this definition in the Moti Ram Case, mentioned below.[18] Although, bail has been understood to include release with or without surety, there is currently some confusion regarding the textual usage of the terms bail and bond. This confusion arises as some provisions in Cr.P.C. use the term bail to include release either with or without surety, however, there are a few provisions that make a distinction between release on bail with surety, and on a personal bond without surety.

Moti Ram v. State of M.P. [1978]

The Supreme Court, in Moti Ram v. State of M.P.[19], expanded on the interpretation of bail and addressed the confusion arising from the Cr.P.C.'s inconsistent usage of the terms "bail" and "bond." It noted that -

While some provisions like the proviso to Section 436, Cr.P.C. imply that bail involves surety and treat personal bond as a fallback for those unable to furnish such sureties, others, like Section 441 Cr.P.C., explicitly distinguish between being “released on bail” and “released on one’s own bond.” Further, S.441(2) and (3) of Cr.P.C use the term bail generically to include release with or without surety.

In resolving this inconsistency, the Court held inter alia that bail ought to include both release with and without surety, and persons who are indigent or unable to pay surety ought to be released on their own recognizance.

Kamalapati Trivedi v. State of West Bengal [1978]

As held by the Supreme Court in Kamalapati Trivedi v. State of West Bengal [1978][20], bail is devised as a for effecting a synthesis of two basic concepts of human values, namely the right of the accused person to enjoy his personal freedom and the public interest; subject to which, the release is conditioned on the surety to produce the accused person in court to stand the trial.

Public Prosecutor v. George Williams alias Victor [1951]

The Madras High Court, in Public Prosecutor v. George Williams alias Victor [1951][21], explaining the concept of ‘bail’, observed that bail or main prize meant, bailment or delivery of the person to their sureties, to be in their custody as opposed to jail. The rationale is that, they being jailors of choice, would have dominion and control over such accused. Hence, sureties are called upon to produce him, as his jailors, in Court, and punished when they fail to do so. If the sureties cannot control the accused person during the period of bail, naturally, the Court would intervene to shift the custody over to the State.

Satender Kumar Antil v. Central Bureau Of Investigation [2022]

The Supreme Court, in Satender Kumar Antil v. Central Bureau Of Investigation [2022][22], held that "A bail is nothing but a surety inclusive of a personal bond from the accused. It means the release of an accused person either by the orders of the Court or by the police or by the Investigating Agency. It is a set of pre-trial restrictions imposed on a suspect while enabling any interference in the judicial process. Thus, it is a conditional release on the solemn undertaking by the suspect that he would cooperate both with the investigation and the trial."

It was also held in this case that "The principle that bail is the rule and jail is the exception has been well recognized through the repetitive pronouncements of the Supreme Court and that it is again on the touchstone of Article 21 of the Constitution of India." The following directions were also given for grant of bail: 1) Not arrested during investigation. 2) Cooperated throughout in the investigation including appearing before Investigating Officer whenever called. This is in line with the case of Supreme Court Legal Aid Committee (Representing Undertrial Prisoners) v. Union of India [1994][23] which held that that some amount of deprivation of personal liberty cannot be avoided in such cases; but if the period of deprivation pending trial becomes unduly long, the fairness assured by Article 21 would receive a jolt.

The State vs Captain Jagjit Singh [1961]

The Court, in the case of The State vs Captain Jagjit Singh [1961][24], opined that whenever an application for Bail is made to a court, the first question it has to decide is whether the offence is bailable or non-bailable. If the offence is bailable, bail will be granted under S.436, Cr.P.C.If the offence is non-bailable, considerations such as the nature and seriousness of the offence, the character of the evidence, circumstances peculiar to the accused, a reasonable possibility of the presence of the accused not being secured at the trial, reasonable apprehension of the witnesses being tampered with, the larger interests of the public or the state and similar other considerations should be taken into account before granting bail.

Restrictive Bail Provisions in Special Laws

Many special laws in India reverse the burden of proof making bail as an exception instead of the rule. Some of these laws have imposed further twin conditions to grant bail essentially turning the common law principle of “presumption of innocence” upside down.

Section 37 of the NDPS Act holds that a court can grant bail to an accused only if it is satisfied that there are reasonable grounds for believing that he is not guilty of the offence and that he is not likely to commit any offence while on bail.

However, the Supreme Court, in the case of Mohd Muslim @ Hussain vs State (Nct Of Delhi) has held “Grant of bail on the ground of undue delay in the trial cannot be said to be fettered by Section 37 of the Act, given the imperative of Section 436A which applies to offences under the NDPS Act too,”

Section 45(1) of the PMLA, the twin conditions are that first a public prosecutor must be allowed to contest the bail application, following which the one seeking bail must prove they are not likely to commit a crime while on bail; and must provide reasonable grounds they are not guilty of the crime they have been accused of.

The twin conditions under PMLA were declared unconstitutional in Nikesh Tarachand Shah v. Union of India[25], but the Supreme Court overturned it in the ruling Vijay Madanlal Choudhary v Union of India.

Section 212(6) of the Companies Act also imposes twin conditions the same as under PMLA. Further, in Ashish Mittal Vs Serious Fraud Investigation Office[26] it was held that these twin conditions do not imply that as soon as section 212(6) is triggered, bail must reflexively, immediately or automatically be rejected. It raises the threshold of satisfaction required of the court while considering the grant or denial of bail. At the threshold therefore, it must be seen if there are any allegations against the accused under the relevant Section 447 of the 2013 Act, since otherwise section 212(6) will not come into play at all.

Appearance in the Official Databases

Law Commission Reports

The 78th Report of the Law Commission of India on Congestion of Under-trial Prisoners in Jails suggests enlarging the list of bailable offences, and conditions for release on bond without sureties while discussing the law of bail with a focus on undertrials.

The 268th Report of the Law Commission of India on Amendments to Criminal Procedure Code, 1973 extensively discusses the concept of bail and suggests recommendations to that effect.

The Law Commission of India’s 203rd Report on Section 438 of the Code of Criminal Procedure Code, 1973, seeks the Law Commission’s opinion on the amended version of Section 438 of CrPC dealing with anticipatory bail.

Prison Statistics India

The National Crime Records Bureau’s Prison Statistics India 2021, present data on prison inmates in India and also provides data on number of inmates released on Bail.

National Judicial Data Grid (NJDG)

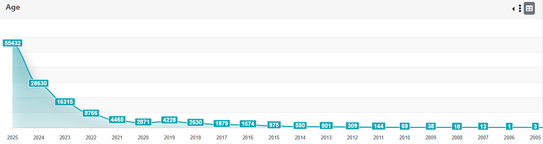

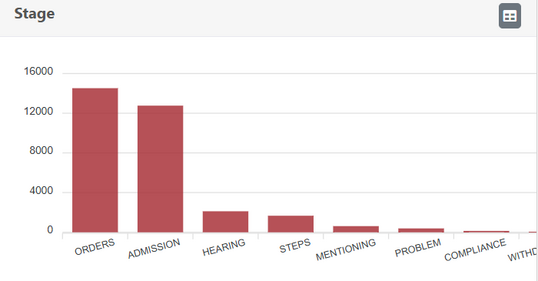

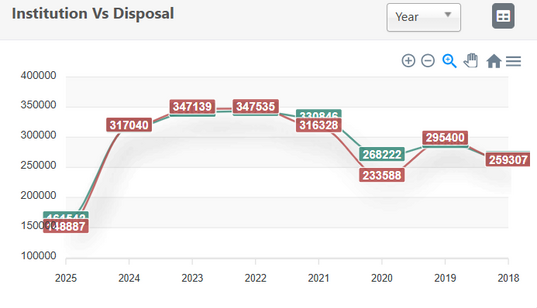

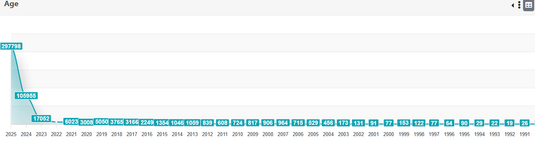

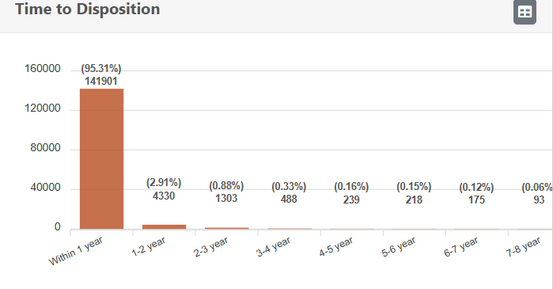

The National Judicial Data Grid (NJDG) (High Courts of India) mentions data for pending bail applications: High Court wise, bench wise and year wise classified into matter-type, age-wise and institution v. disposal.

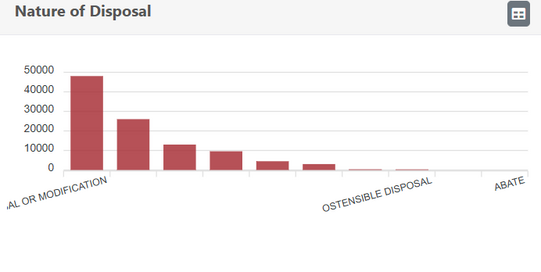

Similarly, the data is available in the Disposed Dashboard of NJDG (High Courts) for the bail applications classified as Matter type, age-wise, nature-wise and time to disposition.

The National Judicial Data Grid (District and Taluka Courts of India) showcase the data for pending and disposed off bail applications district-wise and year-wise under different categories. The information on pending bail applications are categorised as matter-type, age-wise, stage-wise and Institution v. Disposal.

The data is also available for disposed off bail applications district wise and year wise classified as matter type disposal, age-wise disposal, nature-wise disposal and time to disposition.

E-Courts Website

Bail as a case type also features in E-Courts-District Court website as a search filter as ‘Bail Matters-Bail Case Type.

At the District Court level, there is a practice of uploading final order sheets without reflecting the outcome against it. However, some courts like Lucknow District Court upload final order sheets reflecting their outcomes.

High Courts

As Case Type

- High Courts like that of Delhi, Jammu and Kashmir, Kerala, Meghalaya and Sikkim mention “bail application” in their case types.

- High Courts of Bombay, Gauhati, Manipur, Orissa, Tripura and Jharkhand mention two heads as case type for bail matters- Bail and Anticipatory Bail.

- Allahabad High Court has three case types finding mention of bail: Criminal Miscellaneous Anticipatory Bail Application under Section 438 Cr.P.C, Criminal Miscellaneous Bail Application and Criminal Miscellaneous Bail Cancellation Application.

- Rajasthan High Court mentions three case types relating to bail matters: Criminal Bail Cancellation Application, Criminal Miscellaneous Bail Application and Criminal Revision Bail (regular bail).

- Calcutta High Court has an elaborate scheme for bail matters as case types: Anticipatory Bail Applications under Section 438 Cr.P.C., Criminal Miscellaneous Case (Bail Application), Bail applications where sentence may exceed imprisonment for seven years, All bail applications pertaining to FEMA, All bail applications pertaining to FERA, All bail applications pertaining to NDPS Act, All bail applications where sentence does not exceed imprisonment for seven years, and All bail applications pertaining to TADA Act.

- Uttarakhand HC has an even more elaborate scheme for bail matters as case type. It mentions bail as case type under the heads of Anticipatory bail application, Anticipatory bail cancellation application, Bail cancellation First bail application, Second bail application….. upto Tenth bail application, etc.

- Punjab and Haryana HC, Madras HC, Andhra Pradesh, Chhattisgarh HC, Madhya Pradesh HC, Karnataka HC, Patna HC, Telangana HC, Gujarat HC and Himachal Pradesh HC do not have a separate case type pertaining to bail matters,

As Case Category

- Delhi HC lists bail matters under the head of Criminal Revisions, Criminal Miscellaneous Cases and Bail Applications;

- Jammu and Kashmir HC as Criminal Appeal and Bail Application;

- Allahabad HC identifies the bail matters under the category of Application;

- Bombay HC elaborately categorises bail matters as Writ Petition-Fresh Bail Application Pending Investigation of Trial, Writ Petition- Bail, including Anticipatory Bail, Revision-Fresh Bail Application Pending Investigation of Trial, Revision- Bail, including Anticipatory Bail, Revision- Bail, including Anticipatory Bail, Appeal- By Persons Convicted (Against Conviction) on Bail, Application- Fresh Bail Application Pending Investigation of Trial, Application-Anticipatory Bail, For Bail, For Temporary Bail, Jail Application for Bail, Cancellation of Bail, Appeal- By Persons Convicted (Against Conviction) on Bail (By Appointed Advocate), ABA- Cancellation of Anticipatory Bail.

- Madhya Pradesh HC categorises bail matters as Bail Matters:- i. Bail applications u/s 438 Cr.P.C. ii. Bail applications u/s 439 Cr.P.C. iii. Suspension of Sentence u/s 397 Cr.P.C., iv. Suspension of Sentence u/s 389 Cr.P.C., v. u/s 53 Juvenile Justice Act, 2000 / Sec. 102 Juvenile Justice Act,2015 vi. U/s 14A SC/ST Act, 1989 as amended by Amendment Act, 2015;

- Gauhati HC, Manipur HC, Meghalaya HC mention bail matters under the category of Criminal Revisions and Other Cases: (i) Cancellation of Bail (ii) Bail Application under Section 439 Cr.P.C (iii) Anticipatory Bail application under Section 438 Cr. P.C.

DAKSH Database

- The High Court Bail Dashboard by DAKSH analyses data from bail cases in high courts sheds light on the vexing issue of undertrial detention and its burden on the criminal justice system. It analyses the data from bail cases in High Courts and provides insights on types of bail cases, subject matter of bail cases, duration of bail cases, and outcomes of bail cases.

The image is retrieved from https://database.dakshindia.org/bail-dashboard/?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email

Research that engages with Bail

Confused Purposes and Inconsistent Adjudication: An Assessment of Bail Decisions in Delhi's Courts [Cambridge University Press, 2024]

This book by Anup Surendranath and Galen Andrew explores the inconsistencies in bail decisions in Delhi Courts. It highlights how varying interpretations of legal principles and the subjective nature of judicial discretion lead to unpredictable outcomes. The paper argues that these inconsistencies undermine the rule of law and the right to liberty, calling for clearer guidelines and reforms to ensure more uniform and just bail adjudication.[27]

Re-imagining Bail Decision Making [Centre for Law and Policy Research, 2015]

The collaboration of the Azim Premji Philanthropic Initiative and the Centre for Law and Policy Research in their report “Re-imagining Bail Decision Making” analyses bail practice in Karnataka and makes recommendations for reform. The report shows that a staggering 2/3rd proportion of the prison population are undertrial prisoners and points towards better Bail Decision Making process to curb this issue. The study also covers effects of monetary bail system on detainees from marginalized socio-economic backgrounds. It is a comprehensive report on the staggering number of undertrial prisoners, policy reforms and suggestions.[28]

A Study on Bail and Extent of its Abuse Including Recidivism [Tata Institute of Social Sciences, 2017]

This empirical study by Tata Institute of Social Sciences has been carried out to explore the use and potential abuse of bail in the criminal justice system and its impact on recidivism. It also discusses the interface between recidivism and the bail system is stressing the importance of bail in the restorative justice process. A comparative study of recidivism in different countries is also included which provides framework to understand the criminal justice system and the law and order in India. It analyses sociological and legal aspects of the bail system as it operates on the ground level and also breaks some popular assumptions.[29]

Bail Reforms in the Context of Undertrial Women Prisoners: An Action-Oriented Research with Special Reference to Sabarmati Central Jail in the State of Gujarat [Gujarat National Law University, 2021]

This study by Dr. Jagadeesh Chandra and Dr. Saurabh Anand covers the situation faced by women undertrial prisoners in India and the various policy reforms which can bring a change. It points out that overcrowding in prisons has reached a chronic stage and as the prison system is collapsing, the greatest hardship is being faced by women. Due to their gender women often face discrimination due to lack of prison infrastructure or discrimination due to resultant social stigma caused by imprisonment, and they also find it difficult to secure bail or even get a surety when bail is granted to them. As a result, their right of getting a fair trial is hindered and they often suffer imprisonment without following the due process of law.[30]

How the Supreme Court speaks in contradictory voices on bail [Vineet Bhalla, 2024]

The article by Vineet Bhalla discusses the Supreme Court of India's inconsistent approach to granting bail, highlighting contradictory rulings and the resulting unpredictability in bail decisions. It points out that different benches of the court have issued conflicting orders regarding similar bail conditions, leading to a "judicial lottery" where outcomes heavily depend on the individual judges' discretion. The inconsistency extends to cases under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act and notable examples of selective liberty, affecting both political figures and activists. The article calls for standardized guidelines to ensure fair and uniform bail decisions.[31]

Inconsistent and Unclear: The Supreme Court of India on Bail [NUJS Law Review, 2013]

This paper by Vrinda Bhandari analyzes the legal framework surrounding bail and pre-trial detention in India, focusing on how judicial decisions align with the principle of the presumption of innocence. It contrasts two Supreme Court rulings - Pappu Yadav v. CBI and Sanjay Chandra v. CBI, the analysis being limited to bail provisions under the Criminal Procedure Code, excluding any special laws.[32]

Handbook on Principles of Bail Conditions [Law and Equity Foundation, Jharkhand, 2024]

This Handbook released by Law and Equity Foundation is comprehensive reference guide for lawyers practicing at the criminal trial and appellate levels, equipping them with an overview of the evolving jurisprudence surrounding bail conditions, The Handbook is currently organized in seven broad categories of case law i.e. general principles of bail conditions, extremely onerous bail bonds, onerous conditions on type and number of sureties, restrictions on travel/movement (including location sharing), payment of compensation, and restrictions on speech and behavior of accused.[33]

State of the Indian Judiciary [Daksh, 2016]

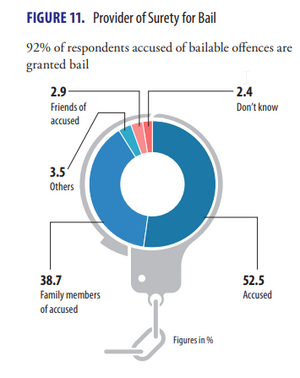

The Report by Daksh involves an Access to Justice Survey (Access to Justice Survey : Introduction, Methodology, and Findings [pg. 138]), the first systematic study in India to explore the needs and expectations of the users of the judicial system—the litigants. The survey assesses how justice is being delivered in courts across the country. It maps litigants’ perceptions on several issues relevant to their experiences in the judicial system, such as the factors that influence the ease with which they can access the system, their ability to use the court system to resolve disputes effectively, the quality of judicial services, and the socio-economic fallout of judicial delay. The survey also gathers essential information about the background of litigants, nature of cases they are involved in, relationship between opposing litigants, and previous litigation experience. [34]

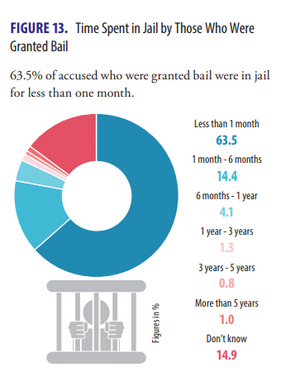

Following data reflects upon the aforementioned:

International Experiences

United States of America

In American law, Bail is the money a defendant pays as a guarantee to be present in court when called upon. A failure to present in court triggers the bond obligation allowing the court to keep the money given as security. According to the American Bar Association, the judge or magistrate decides the amount of bail by weighing many factors, including the risk of the defendant fleeing, the type of crime alleged, the "dangerousness" of defendants, and the safety of the community among others.[35]

Different states have different bail practices, but most follow the common method of determining whether to jail the person without the possibility of release until the case is over. A person may be detained pretrial only if there is a high risk that the person will not appear in court or will be a danger to the community. The Eighth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution prohibits “excessive bail,” but it does not require courts to allow bail.[36]

The Federal Pretrial Risk Assessment (PTRA) is a scientifically based instrument created by the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts (AO) and used by the probation and pretrial services officers to assist in determining a defendant’s risk of failure to appear, new criminal arrests, or technical violations that may lead to revocation while in the pretrial services system.[37]

Pretrial risk assessment tools include characteristics of the defendant, their social environments, or their circumstances. These typically include the defendant's age, substance use, criminal history, pending/current charge(s), employment stability, education, housing/residential stability, family/peer relationships, and community ties.

Risk factors are characteristics that increase the likelihood of failure to appear and/or rearrest, while protective factors are characteristics that decrease the likelihood of failure to appear and/or rearrest. State laws authorize, require, encourage, or regulate court use of pretrial risk assessment tools.[38]

Several states utilize pretrial risk assessment tools in varying ways and with different mandate. For instance, New Jersey has a statewide pretrial services program that administers pretrial risk assessments and offers recommendations to courts. Utah has no law addressing pretrial risk assessment, but the state courts have implemented a tool in many cases. Colorado requires that courts should consider the results of the tool whenever possible. While Vermont allows judges to request a risk assessment in particular cases, the defendant's participation is voluntary. Idaho and New York do not require or encourage the use of a risk assessment tool but instead offer guidelines and requirements that all jurisdictions must follow if they choose to use one. Nevertheless, judges still have their discretion along with using risk assessment tools, and no state requires courts to adhere to the results.[39]

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom enacted a special Bail Act in 1976, which follows a “simple procedure” and provides for bail to all those to whom it is applicable, except as provided in Schedule 1 of the Act. Schedule 1 provides for different contingencies and factors, including the nature and continuity of the offence. Bail can be either unconditional or conditional. Conditional bail means that restrictions and conditions are imposed on defendants. This may mean the defendant can’t contact a complainant or go to a certain location. While unconditional bail means that there are no restrictions and conditions imposed on defendants. It is usually granted when there is no flight risk and it is unlikely that the defendant will reoffend or interfere with victims and witnesses.[40] In the UK, bail is based on cash deposits and specified restrictions on individual liberty.[41]

The bail can be of three types -

- Pre-charge bail or police bail - The police can impose this bail when they have arrested and detained a suspect but do not have the evidence to charge them, the suspect must be released. They can be released either on pre-charge bail (also known as police bail), “under investigation” (RUI), or with “no further action”. Pre-charge bail may be imposed by the police for several reasons. This includes instances where there is insufficient evidence to charge the suspect, and they are released pending further investigation. Additionally, pre-charge bail may be imposed when the police believe there is enough evidence to charge, but the matter needs to be referred to the CPS for a charging decision. Finally, pre-charge bail may be imposed when it is no longer necessary to detain the suspect for questioning, but the police are unable to charge the suspect. However, It is for the police to decide whether a suspect is released with or without bail and if released on bail, whether any conditions of bail should be imposed.[42]

- Post-charge bail - This kind of bail is imposed by the police where there is sufficient evidence against an individual who has been charged. It is at the discretion of the police to keep them in detention or release them on bail to appear at court on a future date and may also impose conditions on that bail.

- Court bail - This kind of bail is imposed by the courts when an individual has been charged.

Australia

The Australian state of New South Wales in 2013 enacted a comprehensive Bail Act to replace a 1978 law. The new legislation introduced the concept of “unacceptable risk” in bail, which considers whether the accused would pose a threat by failing to show up in court, committing a serious crime, or endangering the victim, society, or evidence while granting bail.

On the federal level, Australia has similar specific legislation, which allows for the grant of bail except in certain cases, such as specific offences or while serving a jail sentence. The law also outlines conditions and undertakings for the one who is given bail.[41]

Related Terms

The distinction between the “bail” and “bond” is unclear in light of the reading of Sections 436 and 436A which use these terms interchangeably. Section 436 deals with release of the accused on bail by furnishing a bond for bailable offences and Section 436A poses a condition for release of an undertrial on personal bond. It seems that since bail is always accompanied by some kind of bond whether personal or monetary with or without surety, the legislation dilutes the difference between the two in legalese.

This distinction, however, has been drawn by the BNSS which defines bail, bail bond and bond distinctively under Section 2(1). Accordingly, bail is granted to an accused person or suspected of commission of an offence from the custody of law upon certain conditions imposed by an officer or Court on execution by such person of a bond or a bail bond. A bail Bond means an undertaking for release with surety while a Bond means a personal bond or an undertaking for release without surety.

References

- ↑ Black's Law Dictionary 177 (Revised 4th ed.)

- ↑ Halsbury's Law of England, Vol 11 para 166 (4th ed.)

- ↑ Wharton’s Law Lexicon 105 (14th ed.)

- ↑ State of Maharashtra v. Sitaram Popat Vital, 2004 Supp(3) SCR 696

- ↑ Satender Kumar Antil v. CBI & Anr., (2021) 10 SCC 773

- ↑ https://cdnbbsr.s3waas.gov.in/s3ec05abdeb6f575ac5c6676b747bca8d0/uploads/2024/01/2024010535.pdf

- ↑ https://districts.ecourts.gov.in/sites/default/files/Communication_guidelines%20_Satendar%20Kumar%20Anil%20Vs%20CBI.pdf

- ↑ In Re Policy Strategy for Grant of Bail v. Mr Gaurav Agrawal, SMWP (Criminal) No. 4/2021

- ↑ Munnesh vs State of Uttar Pradesh, Appeal (Crl.) No(s). 1400/2025

- ↑ Dolat Ram v. State of Haryana, (1995) 1 SCC 349

- ↑ Deepak Yadav v. State of U.P, (2022) 8 SCC 559

- ↑ Kunal Kumar Tiwari v. State of Bihar, (2018) 16 SCC 74

- ↑ Munish Bhasin v. The State, (2009) 4 SCC 45

- ↑ Aparna Bhat v. State of M.P., 2021 SCC OnLine SC 230

- ↑ State of A.P. v. Challa Ramkrishna Reddy, [2000] 3 S.C.R. 644

- ↑ Frank Vitus v. Narcotics Control Bureau & Ors., [2024] 7 S.C.R. 97 : 2024 INSC 479

- ↑ Sunil Fulchand Shah v. Union Of India And Ors, 2000 (3) SCC 409.

- ↑ Moti Ram v. State of Madhya Pradesh, AIR 1978 SC 1594.

- ↑ Moti Ram v. State of Madhya Pradesh, AIR 1978 SC 1594.

- ↑ Kamalapati Trivedi v. State of West Bengal, AIR 1979 SC 777.

- ↑ Public Prosecutor v. George Williams alias Victor, AIR 1951 MADRAS 1042.

- ↑ Satendra Kumar Antil v. Central Bureau of Investigation & Anr. (2021) 10 SCC 773.

- ↑ Supreme Court Legal Aid Committee (Representing Undertrial Prisoners) v. Union of India (1994) 6 SCC 731.

- ↑ State v. Captain Jagjit Singh, AIR 1962 SC 253

- ↑ Nikesh Tarachand Shah v. Union of India, AIR 2017 SUPREME COURT 5500

- ↑ Ashish Mittal Vs Serious Fraud Investigation Office ,BAIL APPLN. 251/2023

- ↑ Surendranath, Anup and Andrew, Gale. 2024. "Confused Purposes and Inconsistent Adjudication: An Assessment of Bail Decisions in Delhi's Courts." Cambridge University Press, April 24. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/asian-journal-of-comparative-law/article/abs/confused-purposes-and-inconsistent-adjudication-an-assessment-of-bail-decisions-in-delhis-courts/D3DF8ED4B9F910A8BDAE44D15D6FB70E

- ↑ Jacob John, Neelima Karath, Sudhir Krishnaswamy, Jayna Kothari, et al. 2015. “RE-IMAGINING BAIL DECISION MAKING.” CENTRE FOR LAW & POLICY RESEARCH. https://clpr.org.in/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/BailReport_AW_Web_Final.pdf

- ↑ Tiwari, Aravind. 2017. "A Study on Bail and Extent of Its Abuse including Recidivism." Tata Institute of Social Sciences. https://www.svpnpa.gov.in/static/gallery/docs/28_bailandextension.pdf

- ↑ Chandra, Dr. Jagadeesh and Anand, Dr. Saurabh. 2021. "Bail Reforms in the Context of Undertrial Women Prisoners: An Action-Oriented Research with Special Reference to Sabarmati Central Jail in the State of Gujarat." Gujarat National Law University. https://cdnbbsr.s3waas.gov.in/s35d6646aad9bcc0be55b2c82f69750387/uploads/2021/11/2021112337.pdf

- ↑ Vineet Bhalla. 2024. "How the Supreme Court speaks in contradictory voices on bail." Scroll, June 14. https://scroll.in/article/1070530/how-the-supreme-court-speaks-in-contradictory-voices-on-bail

- ↑ Vrinda Bhandari. 2013. "Inconsistent and Unclear: The Supreme Court of India on Bail". 6 NUJS L. Rev. 549. https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/nujslr6&div=32&id=&page=

- ↑ Vibha Swaminathan, Shailesh Poddar. 2024. "Handbook on Principles of Bail Conditions." Law and Equity Foundation, Jharkhand. https://www.lawandequity.in/_files/ugd/951abe_6357b4caa8a84594a970c34024dc1636.pdf

- ↑ Daksh. 2016. "State of the Indian Judiciary" https://www.dakshindia.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/State-of-the-Judiciary.pdf

- ↑ ‘Bail’ (Legal Information Institute) <https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/bail> accessed 28 May 2024

- ↑ ‘Bail, Bonds, and Relevant Legal Concerns’ (Justia, 15 October 2023) <https://www.justia.com/criminal/bail-bonds/> accessed 28 May 2024

- ↑ ‘Pretrial Risk Assessment’ (United States Courts) <https://www.uscourts.gov/services-forms/probation-and-pretrial-services/supervision/pretrial-risk-assessment#:~:text=The%20federal%20Pretrial%20Risk%20Assessment,new%20criminal%20arrests%2C%20or%20technical> accessed 28 May 2024

- ↑ (Pretrial risk assessment tools) <https://www.safetyandjusticechallenge.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Pretrial-Risk-Assessment-Primer-February-2019.pdf> accessed 27 May 2024

- ↑ ‘Summary Pretrial Release: Risk Assessment Tools’ (National Conference of State Legislatures) <https://www.ncsl.org/civil-and-criminal-justice/pretrial-release-risk-assessment-tools#:~:text=Based%20on%20available%20information%2C%20the,the%20length%20of%20the%20defendant’s> accessed 28 May 2024

- ↑ ‘Bail’ (His Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire & Rescue Services) <https://hmicfrs.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/glossary/bail/> accessed 28 May 2024

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Jain A, ‘How US & UK Made Bail the Rule, Jail the Exception, and Why SC Wants Specific Law in India’ (ThePrint, 17 July 2022) <https://theprint.in/judiciary/how-us-uk-made-bail-the-rule-jail-the-exception-and-why-sc-wants-specific-law-in-india/1038612/> accessed 28 May 2024

- ↑ ‘Bail’ (Bail | The Crown Prosecution Service) <https://www.cps.gov.uk/legal-guidance/bail> accessed 28 May 2024