Child in conflict with law

This page is now open for community updates

"Children in Conflict with Law" (CCL) refers to individuals under the age of eighteen who become involved in the legal system due to their alleged involvement in criminal activities. The Juvenile Justice System assumes that a child offender is a product of unfavorable environment and is entitled to a fresh chance to begin his life. The offences may have been committed without any criminal intent on certain occasions. The child probably lacks foresight on the repercussions/consequences of his actions. It is accepted that a child offender should not be given punishment based on the kind of offence he /she has committed but should be given an individual treatment which is reformative in nature and which is based on his /her need, psychological and social background.

Official definition of child in conflict with law

The Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015, which repealed the 2000 Act has dropped the differential usage of Juvenile and Child. The term Juvenile in Conflict with Law has been replaced by Child in Conflict with Law to remove the negative connotations associated with the former term. It aims to address the apprehension, detention, prosecution, punishment, rehabilitation, and social reintegration of children in conflict with the law. This is indeed an important recognition of the rights of all children. Further, while the erstwhile 2000 Act defined a juvenile who is alleged to have committed an offence and has not completed eighteenth year of age as on the date of commission of such offence; the 2015 Act not only mentions ‘alleged’, but has also added ‘or found’ to have committed an offence’ to ensure a child-centred and rights-based approach to all programming and action for children, even if they were found guilty for having committed an offence.

Child in conflict with law as defined in legislation(s)

The Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015 lays down that notwithstanding anything contained in any other law in force, it is the provisions of only the JJ Act that will apply to a child who has offended including apprehension (the law has done away with the term arrest in its effort to be child sensitive); detention; prosecution; penalty; imprisonment, rehabilitation and social integration of CICL.[1]

The Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015

Section 2 (13) of The Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015 defines “child in conflict with law” as a child who is alleged or found to have committed an offence and who has not completed eighteen years of age on the date of commission of such offence.

Section 74 - 89 of Chapter IX of the Act provides offences against the children in a detailed format. It includes crimes like disclosing information about a child who is a victim of a crime, in need of care, or in conflict with the law,[2] assault, abandonment, abuse, and neglect likely to cause mental or physical suffering. Other offences include employing a child for begging[1], giving intoxicating substances such as alcohol or drugs without a doctor's order[3], and using children to sell or smuggle such substances[4]. Additionally, engaging children in bondage for employment, withholding their earnings, or using them for one's benefit[5] is considered an offense. Illegal adoption procedures[6], the sale or purchase of children[7], corporal punishment in child care institutions[8], and the recruitment of children by militant groups[9] are also criminalized. Kidnapping, abduction [10]and crimes committed against disabled children[11] are recognised as severe offences.

If a child commits any of these offenses, they will be considered a child in conflict with the law under the Juvenile Justice Act[12].

A child who is alleged or found to have committed an offence and who has not completed the eighteenth year of age on the date of commission of such offence is considered a “Child in Conflict with Law” Sec. 2 (13). For determining applicability of JJ Act over a person, relevant date is “Date of Commission of Offence”. Considerable confusion arises in dealing with cases where a person who was a child at the time of commission of offence but turns adult subsequently. Section 5 and Section 6 of the JJ Act 2015 deal with situations where (1) a child completes the age of 18 years during the pendency of inquiry and (2) a person is apprehended for committing an offence when such person was below the age of 18 years. The law is abundantly clear that persons mentioned above shall continue to be treated as children and orders will be passed as if such person continues to be a child, irrespective of such person having turned adult. Additionally, there is confusion regarding the placement of a person or a child - who may have crossed the age of 18 years at the time of apprehension or in the course of the inquiry - in an institution. The JJ Act is very clear on this. It states (section 49 of JJ Act 2015) that for such persons or children (if apprehended after the age of 18 years) the State Government shall set up at least one place of safety in a state, duly registered under section 41, in which such persons or children shall be placed. A CICL, who is between the age of sixteen to eighteen years and is accused of or convicted for committing a heinous offence shall also be placed in a Place of Safety.[4]

Legal provisions relating to child in conflict with law

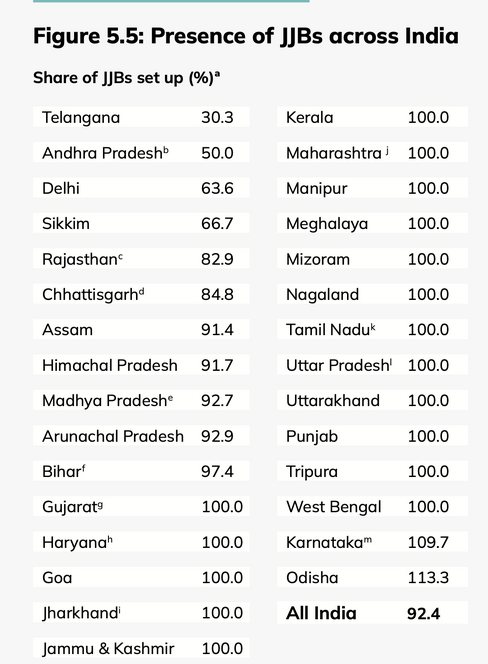

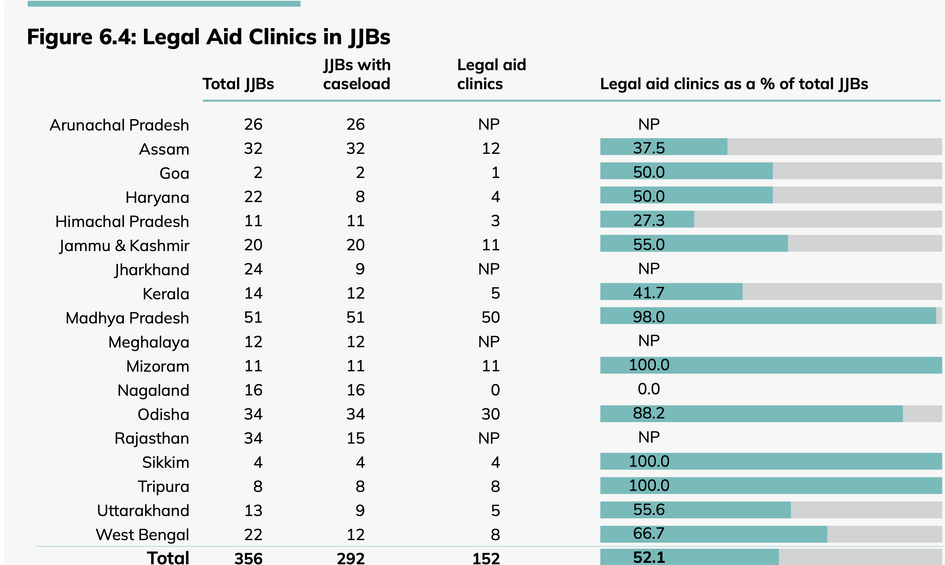

Juvenile Justice Board

Juvenile Justice Board is the concerned authority with a primary motive to deal with Children in conflict with Law[13]. It acts as a separate court for juveniles accused of petty, serious, or heinous crimes as they cannot be taken to a regular criminal court. The main responsibility of the board is to provide care, treatment, protection, developmental needs, inquiry, and final order for the ultimate rehabilitation of juveniles in conflict with the law. JJB consists of a Chief Judicial Magistrate or Metropolitan Magistrate (experience of at least 3 -years) and two social workers, provided that at least one of them should be a woman[14]. A child in conflict with law may be produced before an individual member of the Board, when the Board is not in sitting[15].

The Board ensures to keep the accused juvenile’s parents or guardians informed at every step of the process[16]. Also, they ensure that all the rights of the child are protected as well as legal aid via legal service institutions should be made available for juveniles[17].The Board should provide an interpreter or translator for the child if they are unable to understand the language used during the proceedings[18]. It may request the submission of a social investigation report by the officers within fifteen days of the child's production before the court to determine the circumstances of the case[19]. The Board should also collaborate with the Child Welfare Committee when a Child in Conflict with the Law (CCL) is identified as a Child in Need of Care and Protection (CNCP)[20]. The final order should emphasize rehabilitation, with continued support and follow-up by a Probation Officer, the District Child Protection Unit, or a member of a non-governmental organization, as required[21].

Classification of Offences

Petty Offences

Defined under Section 2(45) as offences for which the maximum punishment under the Indian Penal Code or any other law is up to three years of imprisonment. Such cases are resolved by the Board through summary proceedings as per the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973.

Serious Offences

Defined under Section 2(54) as offences punishable with imprisonment between three to seven years. These cases are handled by the Board following strategic procedures for preliminary trials in summons cases under the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973.

Heinous Offences

Defined under Section 2(33) as offences for which the minimum punishment under the Indian Penal Code or any other law is imprisonment for seven years or more.

Procedures in relation to Child in Conflict with Law

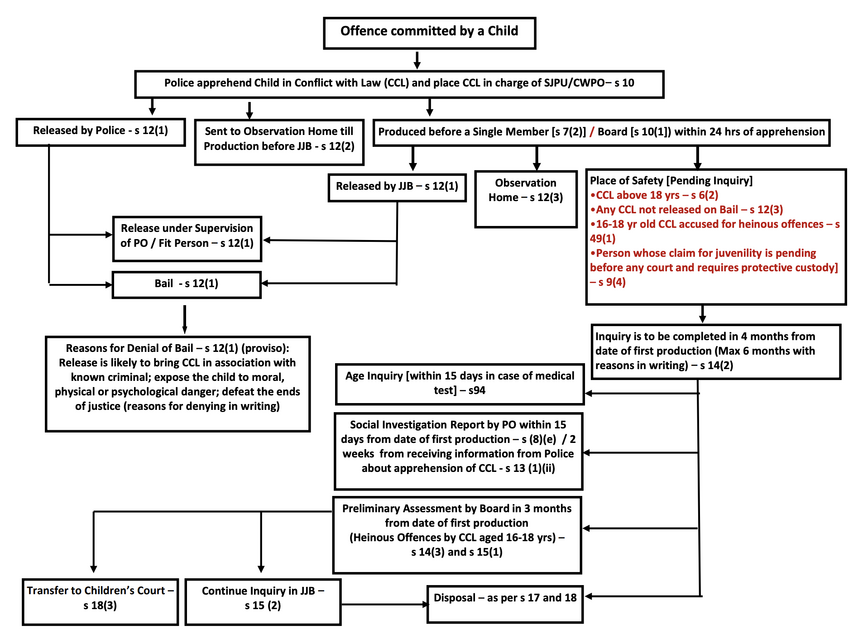

Apprehension

Section 10 defines the procedures to be followed If a child alleged to be in conflict with the law is apprehended by the police. The child will be placed under the charge of the special juvenile police unit or designated child welfare police officer, and the child will be produced in court within 24 hours of apprehension. The child cannot be placed in a lockup or lodged in jail[22].The person in charge of the child assumes responsibility for their welfare, and the child remains with them for the time specified by the Board, unless released by appropriate legal proceedings[23]. Where a child alleging to be in CCIL is apprehended, the designated officer should inform the parent or guardian to be present before the court, and a social investigation report should be submitted within 2 weeks by the child welfare officer. They should be informed about the status of bail for the child[24]. When a child alleged to be in conflict with the law is apprehended, the officer designated as Child Welfare Police Officer of the police station, or the special juvenile police unit shall, as soon as possible, inform the parent or guardian of the apprehension. The probation officer or a Child Welfare Officer shall be informed to prepare and submit a "Social Investigation Report" to the Board within two weeks of apprehension.

Bail

A child alleged to be in conflict with law should be released on bail with or without surety or placed under the supervision of a probation officer or under the care of any fit person. If there is any reasonable ground to believe that the release is likely to bring that person into association with any known criminal or expose the child to moral, physical, or psychological danger, or if the person’s release would defeat the ends of justice, the bail can be denied and can be kept at the observation home. When a child in conflict with the law is unable to fulfil the conditions of the bail order within seven days of the bail order, such child shall be produced before the Board for modification of the conditions of bail.[25]

Inquiry

Inquiry should be completed within 4 months from the first production and unless extended to max 2 more months. A preliminary assessment in case of heinous offences shall be disposed of by the Board within a period of three months, provided that extension can be asked in serious or heinous crimes. If the inquiry for petty offences remains inconclusive even after the extended period, the proceedings shall stand terminated[26]. If the child is found not to have committed an offence, they are released, and if in need of care and protection, they may be referred to the Child Welfare Committee.[27].

Preliminary Assessment

In cases of heinous offences allegedly committed by a child aged 16 or older, the Juvenile Justice Board must conduct a preliminary assessment of the child's mental and physical capacity to commit the crime. This includes evaluating the child's ability to understand the consequences of the offence and the circumstances surrounding the incident. Section 15 describes the method of analysis for the preliminary assessment of the child alleged to be in conflict with the law in the case of heinous offences.[28] it lays down that a child, who has completed or is above the age of 16 years, will be put through a preliminary assessment test with regard to the mental and physical capacity to commit such offence and the ability to understand the consequences of the offence and the circumstances under which the child allegedly committed the offence.

After the receipt of preliminary assessment from the Board under section 15, the Children's court may decide that there is no need trial of the child as an adult as per the provisions of the Code of Criminal Procedure.[29] While the Children's court is to decide on the need for trial of the child as an adult, its powers cannot extend to determining the mental or physical capacity of the child to commit the crime and understand its consequences.

Claim of juvenility

A claim of juvenility may be raised at any stage of a criminal proceeding, even after final disposal, either before a Court or a JJ Board. An abstract formula for age determination is neither feasible nor desirable, and a hyper-technical approach should be avoided. If two interpretations are possible based on the same evidence, the Court should lean toward holding the accused as a juvenile in borderline cases.

The age determination process is provided under Section 94 of the Juvenile Justice Act of 2015.The Committee or Board may observe the individual to assess their age[30]. In cases where there are reasonable doubts regarding the age, the Committee or Board may seek evidence under by collecting[31]:

- the date of birth certificate from the school, or the matriculation or equivalent certificate from the concerned examination board,

- the birth certificate issued by a corporation, municipal authority, or panchayat,

- in the absence of both of the above, the age shall be determined through an ossification test or any other latest medical age determination test ordered by the Committee or Board.

These tests should be completed within 15 days from the order of the authorities, and the age thus recorded will be deemed the true age of the person for the purposes of this Act.

Child Welfare Committee

The state government appoints one or more Child Welfare Committees for exercising the powers and to discharge the duties conferred on such committees in relation to children in need of care and protection. The powers of the committee extend to disposal of cases for the care, protection, development and rehabilitation of children in need of care and protection, as well as to provide for their basic needs and protection.

Other Provisions

A child cannot be sentenced to death or life imprisonment without the possibility of release[32]. A child in conflict with the law will be tried separately from adults[33], and no proceedings under preventive detention laws shall be initiated against them[34]. There is no disqualification for a child who has committed an offence under this Act, and relevant records will be destroyed after a reasonable time[35]. If a child escapes from a special home, observation home, place of safety, or from the care of a person or institution, they may be taken back into custody and produced before the Board within 24 hours for appropriate measures to be determined[36].

Institutional measures for CCL

Chapter 7 of the Act explains the rehabilitation and social reintegration of CCL, defining institutional facilities and other provisions. Rehabilitation can be undertaken in observation homes, special homes, places of safety, or any other suitable facility according to the situation[37]. All institutions housing CNCP and CCL, whether government-run, voluntary, or NGO-run, must be registered under the Act, regardless of whether they are receiving grants from the Centre/State, in the prescribed manner[38]. Violation of this requirement can attract a penalty of imprisonment for up to one year, a fine of not less than one lakh rupees, or both[39].The three types of stay for children in conflict with law at child care institutions include: protective custody during the pendency of the inquiry; overnight protective stay, which provides shelter to the child and prevents them from being kept overnight at a police station or any unsuitable place (such stays may only be between 20:00 hrs at night and 14:00 hrs the following day); and rehabilitation stay, where the child may be sent to a children’s home, special home, or place of safety.

The institutional facilities under the JJ Act includes :

Observation Homes

The State Government must establish and maintain observation homes, directly or through NGOs, for the temporary care and rehabilitation of children alleged to be in conflict with the law during inquiries. These homes must be registered, and if other institutions are deemed suitable, they may also be registered as observation homes. Rules will guide the management, standards, and services provided, with children segregated based on age, gender, and offense severity[40].

Special Homes

Special homes may be set up for CCL who are found to have committed an offense under the order of the Juvenile Justice Board. These homes focus on rehabilitation and social reintegration, with management and monitoring standards regulated by government rules. Segregation will be based on age, gender, offense type, and the child's mental and physical condition[41].

Place of Safety

“Place of safety” means any place or institution, not being a police lockup or jail, established separately or attached to an observation home or a special home, as the case may be, to receive and take care of the children alleged or found to be in conflict with law, by an order of the Board or the Children’s Court, both during inquiry and ongoing rehabilitation after having been found guilty for a period and purpose as specified in the order. [42]

Aftercare

Support provided to children leaving child care institutions after turning eighteen, helping them reintegrate into society with financial assistance[43].

The child is transferred to their home district's Committee or Board after inquiry and consultation, considering the best interest of the child, if they are from outside the jurisdiction. The transfer of a CCL occurs only after the inquiry, and inter-state transfers involve coordination between the child’s home district Committee and Board. An escort, including a female officer for girl children, will accompany the child within 15 days, with travel allowances provided. The receiving Board or Committee will then focus on the child's restoration, rehabilitation, or social reintegration[44]. A child in a Children's Home or special home can be released to live with a parent, guardian, or authorized person for rehabilitation based on a report from a probation officer or social worker. If the child or guardian fails to meet the release conditions, the child may be returned to the institution. Temporary release periods are counted towards the child's overall stay, but failure to fulfill conditions may lead to an extended stay equivalent to the lapse[45]. A child placed in an institution may be granted leave for special occasions or emergencies for up to seven days under supervision. This time away is counted as part of the child's stay in the home. If a child in conflict with the law fails to return to the special home after the leave period is exhausted, or if permission is revoked or forfeited, the Board may extend the child’s stay for a period equivalent to the time lapsed due to such failure[46].

Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Rules

The Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Rules, 2016, governs the treatment and rehabilitation of children in conflict with the law in India. These rules were developed under the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015, which replaced the previous Juvenile Justice Act of 2000.

The rules explain community service rendered by CCL above age of 14 years[47] and the importance of social background report by Child Welfare Police Officer[48]. The rules also give importance to the fact that sittings of the boards should be only held either at an observation home, near its location, or at an appropriate facility within a Child Care Institution designated for children in conflict with the law under the Act. Under no circumstances is the Board allowed to function within courtrooms or jail premises[49]. The Act also provides institutions like The District Child Protection Unit and Special Juvenile Police Unit which play crucial roles in safeguarding children's rights. The District Child Protection Unit maintains reports on children in conflict with law[50] and provides follow-up care for those who committed heinous offenses[51]. The Special Juvenile Police Unit coordinates police functions related to children[52], ensures no contact between accused and victim, and handles cases of juveniles in conflict with law[53]. Additionally, pending cases are addressed with priority, ensuring all children receive benefits under the Act regardless of age during inquiry or trial, and time spent in custody counts towards sentence or detention period. These measures aim to protect vulnerable children and provide support for those in need[54].

Child in conflict with law as defined in International instruments

The rights of juvenile offenders are defined by a wide range of international instruments, which indicates that there is a need to devote special attention to these juveniles and ensure minimum guarantees of the protection of their rights[55]

Convention of the Rights of the Child (CRC)

Article 40 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989) maintains that State Parties are to recognise the right of every child alleged as, accused of, or recognised as having infringed the penal law are to be treated in a manner consistent with the promotion of the child's sense of dignity and worth. Further, every child alleged as or accused of having infringed the penal law has the following guarantees: presumption of innocence until guilt is proven,[56] a speedy trial by a competent, independent and impartial legal authority,[57] not to be compelled to confess guilt or provide testimony,[58] free assistance of an interpreter in the presence of a language barrier,[59] and complete privacy throughout the proceedings.[60]

UN Standard Minimum Rules for the Administration of Juvenile Justice, Beijing Rules (1985)

The United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Administration of Juvenile Justice ("The Beijing Rules") establish a comprehensive, welfare-oriented framework stipulating that juvenile justice must be an integral part of broader social justice, prioritising the well-being and personal development of the juvenile over punitive measures. Its core principles are parallel with the provisions of the Convention of Child Rights. "Principle of Proportionality" is used as an instrument for curbing punitive sanctions, mostly expressed in terms of just deserts in relation to the gravity of the offence.[61]

UN Guidelines for the Prevention of Juvenile Delinquency (The Riyadh Guidelines)

The UN Guidelines for the Prevention of Juvenile Delinquency (The Riyadh Guidelines) believes in a progressive delinquency prevention approach that focuses on education,[62] care and social support. It also recognises that labelling children as delinquent often has a counter productive effect and reinforced negative behaviour. The legal provisions propose the establishment of an office of ombudsman or similar independent organ who would ensure that the rights and interests of young persons are being upheld.[63]

United Nations Rules for the Protection of Juveniles Deprived of their Liberty, 1990

The United Nations Rules for the Protection of Juveniles Deprived of their Liberty, 1990 set global standards to safeguard the rights and dignity of juveniles in detention. It emphasises that imprisonment should be the last resort and for the shortest possible duration and the focus should stay on rehabilitation and reintegration into society.[64] The rules also call for qualified personnel, regular inspections, and mechanisms for juveniles to make complaints or appeals about their treatment.

Guidelines for the Treatment of Juveniles within Juvenile Justice, Vienna Guidelines (1997)

The Guidelines for the Treatment of Juveniles within Juvenile Justice, Vienna Guidelines (1997) largely goes along the lines of the Convention of the Rights of the Child alongside specific targets such as accurate birth registration,[65] fair age determination, and comprehensive child-centred juvenile justice systems that prioritise rehabilitation over punishment.[66] It urges the governments to provide free legal aid,[67] protect vulnerable groups,[68] prohibit corporal punishment,[69] ensure independent monitoring of custodial facilities,[70] and train all officials in child rights and juvenile justice standards.[71] It also identifies one of the obvious tenets in juvenile delinquency prevention and juvenile justice, the need to address root causes to bring about long term change.[72]

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights - ICCPR (1966)

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights – ICCPR (1966) highlights the need to separate juvenile offenders form adults and be accorded treatment appropriate to their age and legal age with a desirability of promoting their rehabilitation.[73]

Council of Europe Social Reaction to Juvenile Delinquency, 1987

The Council of Europe Social Reaction to Juvenile Delinquency, 1987 (CER(87)20) pushes for a rehabilitative and integrative approach to juvenile delinquency. States are encouraged to prioritise prevention through social policies, education, and support programmes for at-risk youth,[74] while developing diversion and mediation measures to avoid formal criminal proceedings.[75] Juvenile Justice systems must ensure speedy trials and interventions that happen within the child's natural environment.[76] It highlights alternative measures like community service, probation along with a special sentencing regime promoting rehabilitation, semi liberty and post-release support.[77]

Council of Europe Social Relation to Juvenile Delinquency of Juveniles from Migrant Families, 1989

The Council of Europe Social Reaction to Juvenile Delinquency of Juveniles from Migrant Families, 1989 (CER(88)6) provides guidelines for juvenile delinquents from migrant families. Although the substantive and procedural aspects stay the same for migrants and non migrants, social integration would require specialised programmes with a tailored approach for groups with integration challenges. It also emphasises the need for non-discrimination and recognition of specific vulnerabilities.[78]

Unlike legally binding treaties such as the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, the European Convention on Human Rights, and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, rules and guidelines fall under "soft law." Though not enforceable, soft law offers valuable direction for states in shaping their juvenile justice systems.

CCL as defined in Case laws

Evidentiary Standards and Judicial Approach in Juvenility Claims

Numerous case laws delve into the nuances and technicalities of the age determination process and the claim of juvenility.

Ranjeet Goswami v. State of Jharkhand and Others, 2014

In Ranjeet Goswami v. State of Jharkhand and Others, the Supreme Court ruled that if a School Leaving Certificate is available, there is no need for a medical examination by a medical board.[79] It was also noted that medical professionals generally provide an age range rather than a precise age due to the limitations of medical science. When such a range is given, the lower end of the spectrum should be presumed to be the age, aligning with the principle of the “best interest of the child”[80].

Om Parkash v. State of Rajasthan, 1998

In Om Parkash v. State of Rajasthan, however, the Supreme Court adopted a slightly different stance, emphasizing the necessity for courts to exercise extreme caution when scrutinising claims of juvenility in cases involving heinous crimes.[81] This measure ensures that claims of juvenility are not used to evade punishment. Where age records in school documents are questionable, a medical opinion should take precedence. The Court clarified that while medical evidence, such as an ossification or radiological examination, is not definitive proof, it is regarded as significant corroborative evidence in age determination.

Parag Bhati v. State of UP, 2016

Similarly, in Parag Bhati v. State of UP, the Supreme Court expressed caution regarding the benefit of doubt in cases where the age of the accused is uncertain, especially when the accused is involved in severe crimes executed with premeditation, indicating maturity rather than juvenile innocence.[82] The Court held that if documents or certificates appear fabricated or manipulated, then the Juvenile Justice Board (JJB) or Child Welfare Committee (CWC) may rely on medical age assessment reports. However, if the documents are genuine, they serve as conclusive proof of age.

Bhoop Ram v. State of UP, 1989

In Bhoop Ram v. State of UP, the Court determined that in cases of conflict between documentary evidence and a medical report, documentary evidence should be given precedence.[83] This implies that documentary proof alone may be sufficient to establish juvenility. However, in practice, documentary evidence can sometimes be easily obtained through means that may not accurately reflect an individual’s age. Although medical examinations offer additional support, they too are not entirely conclusive, as even medical experts recognize limitations in the accuracy of these tests.

Pratap Singh v. State of Jharkhand, 2005

In Pratap Singh v. State of Jharkhand, the Supreme Court ruled that the relevant date for determining a juvenile's age is the date of the offense, not the date of production before the authority or the court.[84]

In Re: Right to Privacy of Adolescents v. For, 2025

The Supreme Court, in the case of In Re Right to Privacy of Adolescents, 2025, upheld the conviction of a man under the POCSO Act and IPC for engaging in a sexual relationship with a 14-year-old girl, but opted not to impose a sentence.[85] Acknowledging the absence of legal recognition for a minor's consent, the Court considered the exceptional circumstances such as the girl's continued cohabitation with the accused, the birth of their child, and failures of family and state institutions. This led to the granting of extraordinary relief under Article 142 of the Constitution. Stressing that the ruling should not set a precedent, the Court instructed the State of West Bengal to provide support to the victim and her child in terms of shelter, education, and welfare measures. This judgment is a rare example of justice focused on the victim within the stringent parameters of the POCSO Act, underscoring the necessity for a nuanced approach in cases involving adolescents.

Appearances in Database

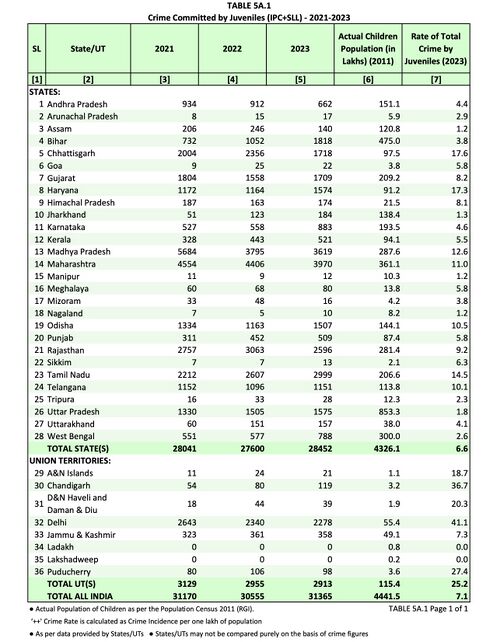

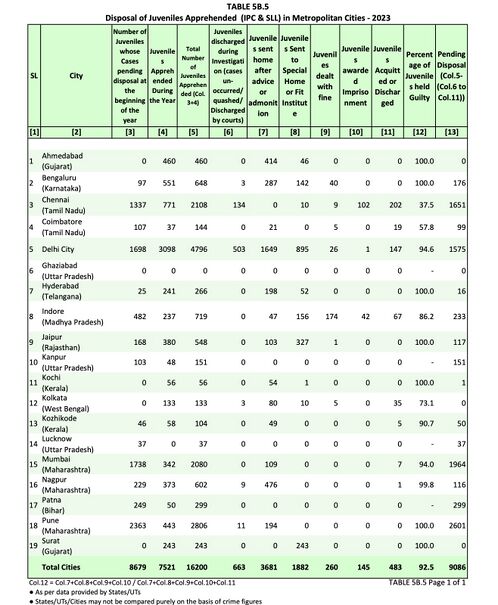

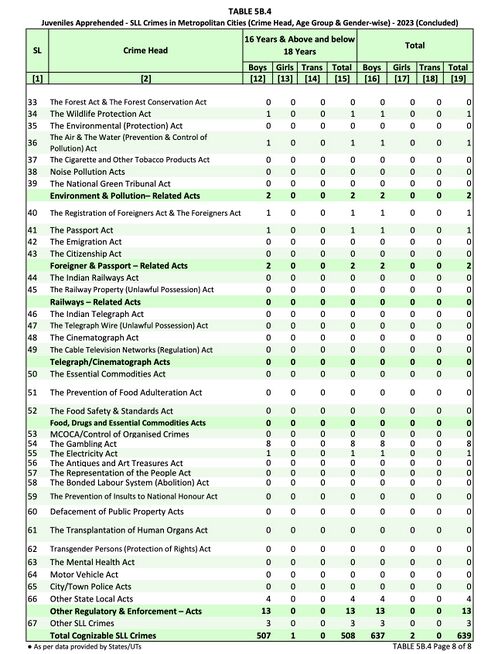

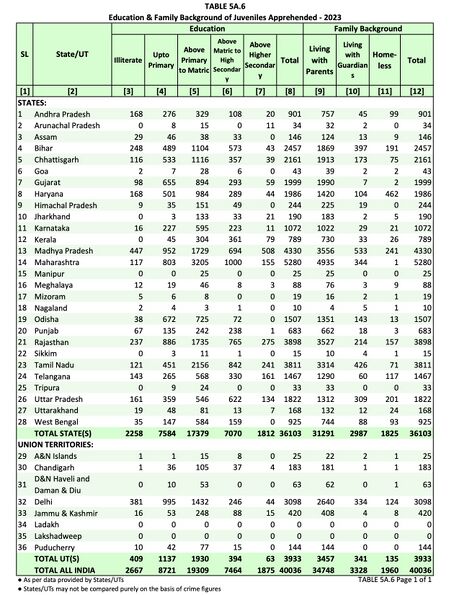

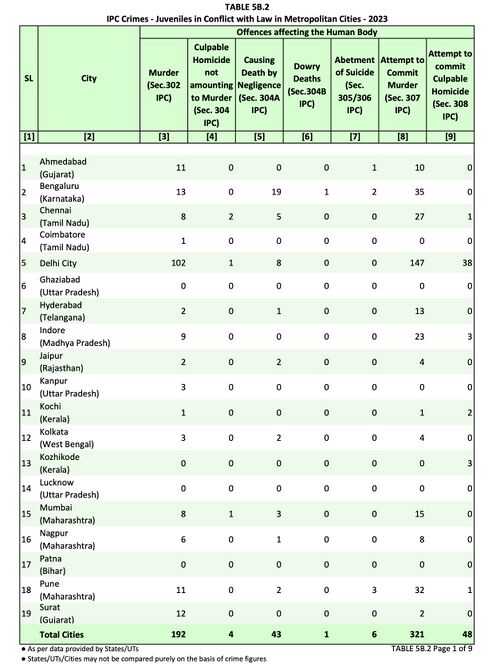

The National Crime Records Bureau, Crime in India Report, 2023

The National Crime Records Bureau Crime in India 2023 report provides various data on juveniles in conflict with the law under IPC and SLL offenses in metropolitan areas. It includes the disposal of juveniles apprehended under different crime heads, along with state-wise and city-wise lists, and statistics on crimes against children[86].

Research that engages with CCL

Pathways and Possibilities for Restorative Justice in India's Juvenile Justice System

The document titled "Pathways and Possibilities for Restorative Justice in India's Juvenile Justice System" by Swagata Raha deeply explores how restorative justice (RJ) principles can transform the juvenile justice system in India, particularly for children in conflict with law (CCLs) and children in need of care and protection (CNCP). It highlights that meaningful rehabilitation of CCLs requires recognition and practice of RJ’s core elements—accountability, victim involvement, dignity, and community participation. The paper critiques the current Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015, especially provisions that allow trial of children aged 16-18 as adults in heinous offences, contrasting this with international child rights standards under the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) which emphasize reintegration and child-centric approaches. The document provides evidence from global jurisdictions where RJ has lowered recidivism, increased victim satisfaction, and facilitated offender accountability through non-adversarial dialogues like victim-offender mediation and family group conferencing. It recommends operationalizing RJ in India by incorporating it as a diversion measure, embedding it within Individual Care Plans (ICP), enhancing safeguards for voluntary participation, reducing stigma, and fostering multi-stakeholder collaboration for rehabilitation. It also calls for systemic reforms for training facilitators and developing protocols aligned with international and regional standards to strengthen India's juvenile justice framework while addressing both victim and child offender needs sensitively and effectively.[87]

Crimes by Children in Conflict with the Law: Heinousness, Acceptability, and Age of Adulthood—A Comprehensive Critique of the Present Juvenile Justice System (NLSIR)

This document titled "Crimes by Children in Conflict with the Law: Heinousness, Acceptability, and Age of Adulthood—A Comprehensive Critique of the Present Juvenile Justice System," published in the National Law School of India Review (2020), critically evaluates India's juvenile justice framework post the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015. It highlights that the shift from a rehabilitative to a retributive model, including provisions to try children as adults for heinous offences, contradicts both international standards and the core objectives of juvenile justice. The authors argue that empirical research questions the scientific basis of assessing maturity and responsibility in children between 7 and 18 years, emphasizing that most children lack the emotional and cognitive maturity required for adult culpability, thus advocating for an increased age of criminal responsibility (MACR) to at least twelve years. The critique underscores procedural deficiencies, inadequate rehabilitation infrastructure, and the need for reforms such as case diversion, community-based solutions, and procedural safeguards to ensure that juvenile justice aligns with international human rights standards and the best interests of children.[88]

New Root Causes of Juvenile Crimes: A Study (ECHO-Center for Juvenile Justice)

This study, "Root Causes of Juvenile Crimes: A Study" by ECHO-Center for Juvenile Justice, Bangalore," conducted in collaboration with the Department of Women and Child Development, District Child Protection Unit, and UNICEF, examines the underlying causes leading children—particularly adolescents—to criminal and anti-social activities, and identifies factors and agents that abet this process. The study, based on 2,500 profiles of juveniles in conflict with law and stakeholder interviews, reveals that most crimes are committed by boys aged 14-18, predominantly from marginalized backgrounds such as families of daily wage laborers, drivers, and petty shop owners, with a significant proportion lacking formal education or parental care. Key findings include: neglect and broken homes, absence of parental supervision, and adverse socio-economic conditions as primary drivers; poor awareness and implementation of juvenile justice mechanisms among police, lawyers, and community workers; frequent police mistreatment and lack of diversion principles; and significant challenges in reintegration due to stigma, lack of family support, and inadequate rehabilitation resources. The study highlights the urgent need for legislative improvements, better capacity building for stakeholders, greater involvement of NGOs, and strengthened community monitoring to provide effective support and rehabilitation for children in conflict with law.

Challenges faced by children in conflict with law and scope for social work interventions

The paper titled Challenges faced by children in conflict with law and scope for social work interventions explores the issues faced by juvenile offenders in India and identifies factors for criminal behavior. The paper highlights that these children encounter stigmatization, disrupted education, and systemic barriers and how social work interventions, such as career guidance, family counseling, and stakeholder sensitization, aids in rehabilitation and reintegration[89].

Study on Rehabilitation of children in conflict with law in India

The paper Study on Rehabilitation of children in conflict with law in India emphasizes the importance of vocational training and psychological intervention for juveniles within the juvenile justice system in India. It highlights that vocational training should be aligned with the interests of juveniles to enhance their employability and foster a sense of responsibility. The need for psychological treatment is also addressed, as many juveniles come from dysfunctional backgrounds requiring support for their emotional and mental health challenges[90].

Reference

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Sec1(4) The Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015

- ↑ S 74 JJ Act 2015

- ↑ S 77 JJ Act 2015

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 S 78 JJ Act 2015

- ↑ S 79 JJ Act 2015

- ↑ S 80 JJ Act 2015

- ↑ S 81 JJ Act 2015

- ↑ S 82 JJ Act 2015

- ↑ S 83 JJ Act 2015

- ↑ S 84 JJ Act 2015

- ↑ S 85 JJ Act 2015

- ↑ S 89 JJ Act 2015

- ↑ S 4(1) JJ Act 2015

- ↑ S 4 (2) JJ Act 2015

- ↑ S 7 (2) JJ Act 2015

- ↑ S 8 (2) (a) JJ Act 2015

- ↑ S 8 (2) (c) JJ Act 2015

- ↑ S 8 (2) (d) JJ Act 2015

- ↑ S 8 (2) (e) JJ Act 2015

- ↑ S 8 (2) (g) JJ Act 2015

- ↑ S 8 (2) (g) JJ Act 2015

- ↑ S 10 JJ Act 2015

- ↑ S 11 JJ Act 2015

- ↑ S 13 JJ Act 2015

- ↑ S 12 JJ Act 2015

- ↑ S 14 JJ Act 2015

- ↑ S 17 JJ Act 2015

- ↑ S 15 JJ Act 2015

- ↑ S 19 JJ Act 2015

- ↑ S 94(1) JJ Act 2015

- ↑ S 94(2) JJ Act 2015

- ↑ S 21 JJ Act 2015

- ↑ S 23 JJ Act 2015

- ↑ S 22 JJ Act 2015

- ↑ S 24 JJ Act 2015

- ↑ S 26 JJ Act 2015

- ↑ S 39(2) JJ Act 2015

- ↑ S 41(1) JJ Act 2015

- ↑ S 42 JJ Act 2015

- ↑ S 42 JJ Act 2015

- ↑ S 42 JJ Act 2015

- ↑ S (46) of JJ Act 2015

- ↑ S 46 JJ Act 2015

- ↑ S 95 JJ Act 2015

- ↑ S 97 JJ Act 2015

- ↑ S 98 JJ Act 2015

- ↑ S 2(vi) JJ rules 2016

- ↑ S 2 (xvi) JJ rules 2016

- ↑ S 6(1) JJ rules 2016

- ↑ S 85 (1)(i) JJ Rules 2016

- ↑ S 85 (1)(iii) JJ Rules 2016

- ↑ S 86 (1) JJ Rules 2016

- ↑ S 86 (9) JJ Rules 2016

- ↑ S 90 JJ Rules 2016

- ↑ Juvenile Justice Reform Commission, THE RIGHTS OF CHILDREN IN CONFLICT WITH THE LAW (2007), https://www.unicef.org/montenegro/media/7931/file/MNE-media-MNEpublication391.pdf

- ↑ Article 40(2)(b)(i)

- ↑ Article 40(2)(b)(iii)

- ↑ Article 40(2)(b)(iv)

- ↑ Article 40(2)(b)(vi)

- ↑ Article 40(2)(b)(vii)

- ↑ Clause 5.1

- ↑ Clause 21

- ↑ Clause 57

- ↑ Clause 1

- ↑ Clause 12

- ↑ Clause 14

- ↑ Clause 16

- ↑ Clause 17

- ↑ Clause 18

- ↑ Clause 21

- ↑ Clause 24

- ↑ Clause 41

- ↑ Article 10(2)(b)

- ↑ Clause I, Prevention

- ↑ Clause II, Diversion-mediation

- ↑ Clause III, Proceedings against minors

- ↑ Clause IV, Interventions

- ↑ Clause II, Police, Clause IV, Interventions and Measures

- ↑ Ranjeet Goswami v. State of Jharkhand and Others 2014 (1) SCC 588, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/166387368/

- ↑ Dr. Malvika Singh, CLAIM OF JUVENILITY: A SECURITY FOR EVER, 2 The Haryana Police Information (2019), https://haryanapolice.gov.in/policejournal/pdf/CLAIM_JUVENILITY.pdf.

- ↑ Om Parkash v. State of Rajasthan 1998 SCC(CRI) 696, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1389578/

- ↑ Parag Bhati v. State of UP (2016) 12 SCC 744, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/85936912/

- ↑ Bhoop Ram v. State of UP (AIR 1989 SC 1329), https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1161696/

- ↑ Pratap Singh v. State of Jharkhand (AIR 2005 SC 2731), https://indiankanoon.org/doc/254131/

- ↑ In Re Right to Privacy of Adolescents, 2025 LiveLaw (SC) 617, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/128730453/

- ↑ National Crime Records Bureau, Crime in India 2022 Vol 1, https://www.ncrb.gov.in/uploads/nationalcrimerecordsbureau/custom/1701607577CrimeinIndia2022Book1.pdf

- ↑ Raha, Swagata. "Pathways and Possibilities for Restorative Justice in India's Juvenile Justice System," 2025. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/50088662/Pathways_and_Possibilities_for_Restorative_Justice_in_Indias_Juvenile_Justice_System

- ↑ Kabra, Aanchal and Panigrahi, Pratyay, "Crimes by Children in Conflict with the Law: Heinousness, Acceptability, and Age of Adulthood — A Comprehensive Critique of the Present Juvenile Justice System," National Law School of India Review, Vol. 32, Issue 1, 2020, Article 4. available at: https://repository.nls.ac.in/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1078&context=nlsir

- ↑ Rachel.S & Gunavathy J.S, Challenges Faced by Children in Conflict with Law and Scope for Social Work Interventions, 18 EBJSW 37 (2022), https://bcmcollege.ac.in/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Challenges-faced-by-children-in-conflict-with-law-by-Rachel-S-and-Gunavathy-J-S.pdf

- ↑ Panduranga B & Dr. Pavitra R Alur, Study on Rehabilitation of Children in Conflict with Law in India, 6 JETIR (2019), https://www.jetir.org/papers/JETIR1904C10.pdf