Civil Appeal

What is a Civil Appeal?

A civil appeal in Indian law is a legal process where a party to a civil case seeks a higher court's review and reversal of a lower court's decision. This mechanism allows for the examination and potential correction of any errors that may have occurred during the initial trial. Civil appeals can be broadly categorized into first and second appeals.

Official Definition of Civil Appeal

‘Civil Appeal’ as defined in Code of Civil Procedure (CPC)

The Code of Civil Procedure does not define Civil Appeal per se but the legislative scheme provides for Appeals from Original Decrees, Appeals from Orders, and General provisions (applicable to both Original Decree and Orders). It primarily deals with two types of Appeals- first appeal and second appeal.

First Appeal

First Appeal lies from the subordinate court to the higher court and is generally understood to be the right to appeal. The right to appeal has been provided under Section 96 of the Code and Order XLI primarily and is available in higher courts including the High Court and the Supreme Court, based on the statute under which the right to appeal is provided.

Nature and Extent of First Appeal

The right to appeal i.e. the first appeal has been provided for in the section 96 of the CPC. The extent of the first appeal, as provided under section 96 of the Code, is limited to decree passed by a subordinate court as defined under section 2(2) of the Code. Furthermore, there are certain exceptions to this rule which are either to be expressly provided for in the code itself or any other law for the time being in force.[1] Section 96, however, is to be read in light of Order XLIII which mentions appeals in case of orders. It must be mentioned that an order that is passed by an authority other than a court of law is not appealable under this provision[2].

Furthermore, an appeal may only be brought by an aggrieved party to the suit[3], but it may extend to a person who was not a party to the original decree if such person is bound by the decision of the court in such a decree or order or aggrieved by it in any other manner[4].

Salient features of first appeal

- An appeal lies from a decree by a court exercising original jurisdiction - An appeal under section 96 lies from a decree as defined under the Section 2(2) of the Code. It is a general rule that the decrees are appealable unless barred by the law. This includes deemed decrees as well. Furthermore, the phrase ‘any court exercising original jurisdiction’ has been interpreted by the honorable court mean a decree passed by a court in the exercise of its original jurisdiction[5].

- An Appeal lies to a court authorized to hear appeal - A court which has not been expressly authorized by law to hear appeals may not entertain any such appeals presented before it. Such a jurisdiction includes the right to hear appeals from the courts in question generally, as well as in particular cases as mentioned under the statute[6].

- An appeal lies against an order passed ex parte - An appeal against an ex parte order/decree cannot be converted into a proceeding to set aside the ex parte decree under Order 9 Rule 13. But the appellant can rely on any ground affecting the merits of the case, i.e. a defect, error or irregularity which has affected the decision of the case[7].

- Limitation period of First Appeal - The limitation period for the right to appeal has been provided under the Limitation act to be ninety days from the date of decree and appeals presented after limitation, for condonation of delay, are dealt with under Rule 3-A of the Order XLI.

- Grounds of first appeal - As per the Rule 2 of the Order XLI, the appellant may only urge such grounds as have been raised in the memorandum of appeal without the leave of the court. However, the courts have the power to decide a matter on any ground which has not been raised by the party in the memorandum. The court has discretionary power with respect to new plea being raised in the appeal, after recording such reasons for allowing the same.

Limitations in First Appeal

- Decree passed with the consent of parties - aThe section 96(3) of the Code states that “No appeal shall lie from a decree passed by the Court with the consent of parties.” It is based on the waiver of the right to appeal by the parties, which is allowed since the right to appeal is merely a statutory and not an inherent right bestowed with the parties. No appeal is maintainable in view of the specific bar that has been contained in the aforementioned provision[8].

2. No appeal in cases where the amount does not exceed ten thousand rupees in cases of Small Cause Courts

Another limitation imposed upon the first appellate court with regards to the admission of the first appeal is that in cases, except where the issues relate to a question of law, that in cases of a decree from any suit under the court of small causes, where the amount does not exceed ten thousand rupees, no appeal shall lie before the appellate court[9].

3. Appeal from final decree where no appeal from first decree

It has been stated in the section 97 of the code that “where any party aggrieved by a preliminary decree passed after the commencement of this Code does not appeal from such decree, he shall be precluded from disputing its correctness in any appeal which may be preferred from the final decree.”

The appeal from an appellate court is termed as second appeal. It is generally not construed within the meaning of right to appeal as understood by various honorable judges, leading to conflicting views on its necessity. There are fairly limited grounds on which a second appeal is allowed before the High Court. The process followed is similar to that of first appeals. The concept of second appeal has been discussed under Section 100 and Order XLII of the Code.

Nature and Extent of Second Appeal

The concept of second appeal, that is the appeal to the decision of an appellate court itself in the first instance, is discussed in the Section 100 of the Code. It is to be noted that a second appeal, in any and every case, lies only to the High court and not any other superior court such as the Supreme Court. Similar to the first appeal, an aggrieved person, which includes a person who is party to the suit or even any other person aggrieved by the decree of the first appellate court in certain cases, may file a second appeal before the High court. “Aggrieved person” has been defined to mean a person who has a genuine grievance against the decree passed by the court which has affected the rights of such person in a prejudicial manner[10].

It can be understood from the text of the code itself that the ambit of the second appeal is limited to cases “involving substantial question of law”, which excludes the questions based on facts. The appellant under the second appeal is not permitted to urge any ground other than that of a question law without the leave of the court. If an appeal is still admitted without a substantial question of law being framed by the court, it can frame such question at any point of time before the hearing of the second appeal[11].

Furthermore, the ambit of such appeals is limited to the plea raised in the lower courts by the party. However, there are certain exceptions to this rule which include a pure question of law or jurisdiction which does not have any connection with the facts of the case in any manner whatsoever as well as thorough study of the matter.

Salient features of Second Appeal

1. Second Appeal involves a “Substantial Question of Law”

“The existence of a substantial question of law is a sine qua non for the exercise of jurisdiction under the provisions of Section 100 of the Code.[12]” Therefore, the jurisdiction provided to the High courts under the Section 100 is limited to the appeal which involve a substantial question of law not merely pure questions of facts[13]. The concept of substantial question of law has been duly explained by the honorable Supreme Court as“

"'Substantial questions of law' means not only substantial questions of law of general importance, but also substantial question of law arising in a case as between the parties. In the context of section 100 CPC, any question of law which affects the final decision in a case is a substantial question of law as between the parties. A question of law which arises incidentally or collaterally, having no bearing in the final outcome, will not be a substantial question of law. Where there is a clear and settled enunciation on a question of law, by this Court or by the High Court concerned, it cannot be said that the case involves a substantial question of law. It is said that a substantial question of law arises when a question of law, which is not finally settled by this court (or by the concerned High Court so far as the State is concerned), arises for consideration in the case.[14]”

2. Formulation of question by the court

It would not be wrong to render a judgment of the High court if a judgment appealed against in such a second appeal is reverse without the formulation of a substantial question of law[15]. The failure of the court to admit second appeal without the formulation of a substantial question of law has been stated to be an error on the part of the court by the honorable Supreme Court[16].

3. Limitation period:

A second appeal before the High court may be filed by the aggrieved person within a period of ninety days from the date of the passing of the decree by the first appellate court.

4. Power of High Court to determine issue of fact

The power of the high court to determine an issue of fact has been discussed under the section 102 of the code which provides two circumstances in which the court may determine such an issue if the evidence on record is sufficient:

a) Firstly, where such question has not been determined by the court of first instance and first appellate court or the first appellate court individually

b) Secondly, where the issue has been wrongly determined by incorrect application of a question of law. Thus, it may not be challenged if the decision of the court was based on proper consideration of evidence and there is no error or defect in the procedure itself[17]. Where a ‘legal’ conclusion has been drawn from the set of facts, it is permitted to file a second appeal on the grounds of erroneous conclusion[18].

Limitations in second appeal: Grounds of Rejection

1. Plea not raised or abandoned

In such cases where a particular plea has not been raised and therefore, abandoned in the lower court, such plea cannot be raised by the party at the stage of appeal, whether first or second appeal[19]. Furthermore, it was seen in another case that where the plea for the abatement of first appeal due to the death of one of the respondents was not raised in the first appeal itself, it cannot be subsequently raised in the second appeal[20]. An appellant is forbidden under law to set up a complete new case in the second appeal[21].

2. Letters Patent Appeal

As provided under the section 100A of the Code, “where any appeal from an original or appellate decree or order is heard and decided by a Single judge of a High Court, no further appeal shall lie from the judgment and decree of the single judge.” It may thus be inferred from the provision that no letters patent Appeal with lie before the High Court in such cases[22].

3. Recovery of money not exceeding twenty-five thousand

It has been stated in the section 102 of the code that “no appeal shall lie from any decree, when the subject matter of the original suit is for the recovery of money not exceeding twenty-five thousand rupees.”

4. Erroneous findings of fact

It has been stated by the honorable court that the use of words “substantial question of law” in the section 100 and subsequently, the provision under section 101 where the it has been stated that a second appeal is not admissible for any other ground purely reflects the intent of the legislature to prohibit second appeal from becoming “third trial on facts” or “one more dice in the gamble.[23]”

Comparison between first and second appeal

There are various differences between the first and the second appeal. However, it would be sufficient to mention the following primary differences between the two:

1. Decision against which an appeal lies

The first appeal lies against decree passed by any court exercising its original jurisdiction. On the other hand, in the case of second appeals, such decree must be passed by an appellate court.

2. Court where the appeal lies

One of the primary points of difference between the first and second appeals is the court where the appeal lies. First appeal under section 96 may be brought before any higher appellate court. However, a second appeal under the section 100 of the Code may only be brought before a High Court and not any other appellate court.

3. Position regarding Letters Patent Appeal

A letters patent appeal can be filed against a ‘judgment’ of a single judge of a High Court before a division bench of the same court. On the other hand, in case of second appeal, no Letters Patent Appeal is maintainable against a judgment rendered by a single judge of the high court in exercise of appellate jurisdiction under Section 100 of the Code.

4. Grounds of appeal

First appeal is maintainable before the court on the grounds not only of a question of law but also a question of fact and a mixed question of law and fact. On the other hand, a second appeal may only be filed before the court in cases where a substantial question of law has arisen.

It was observed in the case of Chacko & Anr. v. Mahadevan[24] that “It may be mentioned that in a first appeal filed under Section 96 CPC, the appellate court can go into questions of fact, whereas in a second appeal filed under Section 100 CPC the High Court cannot interfere with the findings of fact of the first appellate court, and it is confined only to questions of law.”

5. Limitation period for first and second appeal

The limitation period for the right to appeal has been provided under the Limitation act to be ninety days from the date of decree and appeals presented after limitation, for condonation of delay, are dealt with under Rule 3-A of the Order XLI. On the other hand, a second appeal before the High court may be filed by the aggrieved person within a period of ninety days from the date of the passing of the decree by the first appellate court.

6. Valuation of Subject Matter

In the case of first appeals, no appeal lies from small cause courts where the amount does not exceed ten thousand rupees. On the other hand, in the case of second appeal, no appeal lies in cases where the amount awarded in the decree by the appellate court does not exceed twenty-five thousand rupees.

Regional Variations

| Name of District/State | Appeal to District Court | Appeal to High Court |

|---|---|---|

| Andhra Pradesh | From the Court of Civil Judge (Junior Division) - No Limit;

From the Court of Civil Judge (Senior Division) - Rs.50 lakhs[25] |

From District Court - No limit;

From the Court of Civil Judge (Senior Division) - Exceeding Rs. 50 lakhs[26] |

| Maharashtra | Rs. 10 Crores[27] | No limit[28] |

| Goa | All appeals up to Rs. 20 lakhs[29]

From Civil Judge (Special Law) - Rs. 10,000[30] |

From Civil Judge - Exceeding Rs. 20 lakhs[31]From Civil Judge (Special Law) - Up to Rs. 10,000[32] |

| Gujarat | From Senior Civil Judge - Rs. 5 lakhs

From Civil Judge - No limit[33] |

From District Judge - No limit

From Senior Civil Judge - Exceeding Rs. 5 lakhs[34] |

| Karnataka | From Senior Civil Judge - Rs. 10 lakhs[35] | From District Court - No limit[36]

From Senior Civil Judge - Exceeding Rs. 10 lakhs[37] |

| Kerala | From Munsiff’s Court or Subordinate Judge's Court - Rs. 2 lakhs[38] | From District Court or Subordinate Judge's Court - No limit[39] |

| Madhya Pradesh | Appeals from Civil Judges, Junior Division or Civil Judge - No limit[40] | No limit[41] |

| Orissa | From Subordinate Judge - Rs. 1 lakh[42]

From Munsif - No limit[43] |

From District Judge or Additional District Judge - No limit[44]

From Subordinate Judge - Exceeding Rs. 1 lakh[45] |

| Puducherry | From Subordinate Judge or Munsif - Rs. 10,000[46] | From District Judge - No limit

From Subordinate Judge or Munsif - Exceeding Rs. 10,000[47] |

| Sikkim | From Civil Judge - Rs. 5,000[48] | From Civil Judge - Exceeding Rs. 5,000;

From District Judge - No limit[49] |

| Telangana | From Junior Civil Judge - No Limit;

From Senior Civil Judge - Rs. 35 lakhs[50] |

From District Court - No limit;

From Senior Civil Judge - Exceeding Rs. 35 lakhs[51] |

Appearance of 'Civil Appeal' in Database

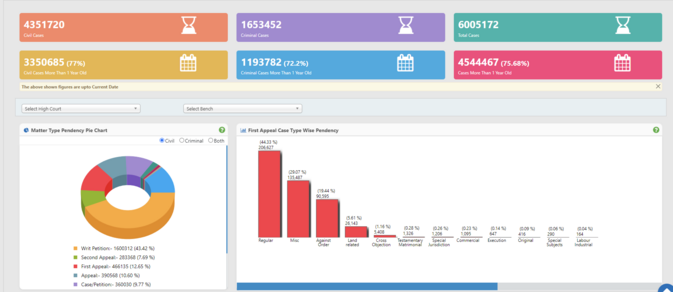

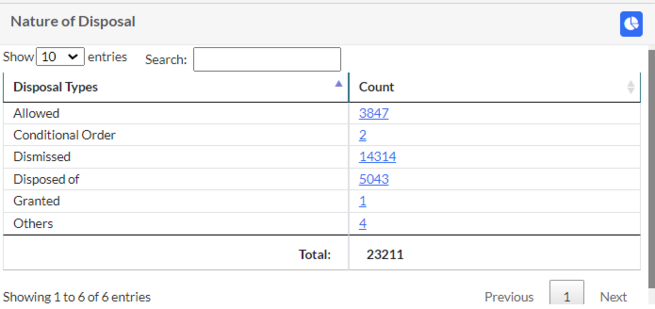

The statistics Civil Appeals appear in National Judicial Data Grid (NJDG) where the statistics of pendency and disposal can be tracked. District Courts, High Courts, and the Supreme Court have separate databases within NJDG.

Database District and Subordinate Courts

Database for High Courts

Database for Supreme Court

Research that engages with 'Civil Appeal'

The Supreme Court of India is grappling with a pressing crisis: an overwhelming backlog of cases and unequal access to justice. These issues are holding the court back from its essential role as the guardian of the Constitution. Today, a huge portion of the court’s time is spent on appeals, particularly Special Leave Petitions (SLPs), which have flooded its docket. As a result, only a small fraction of its workload is dedicated to cases of constitutional importance. For instance, in 2014, only 7% of its judgments dealt with constitutional issues, as routine appeals increasingly took precedence. This imbalance highlights a serious disparity in access. Cases from high courts closer to Delhi—such as those in Punjab & Haryana, Delhi, and Uttarakhand—and from wealthier regions are more likely to reach the Supreme Court. This reality reflects how one’s location and financial resources can impact access to justice at the highest level, affecting citizens from remote or economically disadvantaged areas and underscoring the challenges of delivering equal justice across India[52].

The idea of creating a National Court of Appeal has been discussed for over three decades as one solution to these challenges[53]. Under Article 32, any Indian citizen can approach the Supreme Court, and Article 136 gives it the power to hear appeals from high courts and tribunals. As far back as 1984, the Law Commission suggested dividing the Supreme Court into a Constitutional Division and a Legal Division to make it more accessible and affordable. In 1986, in the case of Bihar Legal Support Society vs. Chief Justice of India[54], the Supreme Court endorsed the idea of a National Court of Appeal to handle routine civil, criminal, revenue, and labor cases, so that the Supreme Court could focus on major constitutional and public law matters. However, some concerns have also been raised; for example, in 2010, then-Chief Justice K.G. Balakrishnan expressed worry that regional benches might erode the court’s unity and public trust.

Despite such concerns, support for regional benches has grown. Figures like Vice President Venkaiah Naidu and Attorney General K.K. Venugopal has advocated for regional benches to make the court more accessible, with proposals for four benches across the country. In 2016, the Supreme Court even considered a petition for a National Court of Appeal, although the government opposed it, calling it a “self-defeating exercise.” Currently, a constitutional bench of the Supreme Court is reviewing these ideas, considering how best to uphold citizens’ fundamental right to judicial access. The recent shift to virtual courtrooms, accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic, has already shown the potential of remote hearings to improve access for rural advocates and litigants, pointing toward a future where virtual regional benches or a National Court of Appeal might bridge the access gap. In addition to this broader vision, several targeted reforms have been proposed to address the Supreme Court’s backlog and refocus its work on constitutional issues. A central recommendation is to create specialized benches within the court to handle specific areas like tax law, criminal law, service law, and land law. By assigning judges with relevant expertise to these benches, the court could manage complex cases more efficiently, freeing up time for its core constitutional responsibilities[55].

Enhancing technology is also crucial. Expanding e-filing and video conferencing options would reduce costs and make it easier for people from remote areas to access the court’s services without needing to travel to Delhi. Setting clearer guidelines for accepting SLPs could help limit the docket to cases of significant public importance, while appointing retired judges on a temporary basis under Article 128 could offer short-term relief from the backlog without expanding the bench size permanently. Improving the court’s internal operations is another step that could make a big difference. Streamlining hiring processes for judicial clerks, involving interdisciplinary experts for cases that require specialized knowledge, and refining administrative processes would enhance the court’s efficiency and help it stay focused on its core mission. By adopting these reforms[56], the Supreme Court could become a more accessible, efficient institution, fulfilling its duty to uphold constitutional values and ensure that justice is available to all citizens, regardless of where they live or their financial means.

Challenges

Addressing the following issues will require urgent reforms focused on equitable judge allocation, streamlined listing procedures, and prioritizing older cases to expedite disposals[57]. Such improvements are essential to restore public trust and ensure that the court system delivers fair and timely outcomes for all litigants.

- Judges are often tasked with multiple types of cases, reducing the time they can dedicate specifically to civil appeals. This limited allocation leads to fewer cases being listed for hearing each day and contributes to slower case disposal rates.

- There is no consistent system for scheduling appeals, and often, less than 2% of pending cases are listed for hearing each day. This inconsistency in listings means that some cases, especially older ones, are repeatedly postponed.

- Lengthy delays often impose financial and emotional strains on litigants, diminishing the value of the eventual judgments they receive and undermining the principle of timely justice.

- The court appears to prioritize other case types, such as writ petitions, over First Appeals and Second Appeals. This disparity exacerbates the backlog of civil appeals, as these cases are continuously delayed in favor of other matters.

- The assignment of cases and judges lacks a strategic approach that would ensure more efficient handling of civil appeals. Judges are often burdened with a mixed caseload, which divides their attention and leads to inconsistent case clearance rates for First Appeals and Second Appeals.

- The presence of long-pending cases—some lingering for two decades or more, demonstrates a failure to address the backlog effectively. These long delays underscore the challenge of delivering timely justice, as litigants face protracted waits that undermine confidence in the judicial system.

References

- ↑ Wishwambhar v. Prabhakar, ILR 8 Bom 269.

- ↑ Janardan Prasad v. Kalindri Prasad, 1963 All LJ 59.

- ↑ State of Punjab v. Amar Singh, (1974) 2 SCC 70.

- ↑ Adi Pherozshah v. H.M. Seervai, (1970) 2 SCC 484.

- ↑ Namdev Devangan v. Seeta Ram AIR 1998 MP 148.

- ↑ Bandiram v. Purna 43 IC 758.

- ↑ Laxmibai v. Keshrimal Jain AIR 1995 MP 178.

- ↑ Pushpa Devi Bhagat v. Rajinder Singh, AIR 2006 SC 2628.

- ↑ Section 96(4), Code of Civil Procedure, 1908

- ↑ Adi Pherozshah Gandhi v. H.M. Seervai, (1970) 2 SCC 484.

- ↑ Malkiyat Kaur v. Hardev Singh, AIR 2011 P&H 93.

- ↑ Municipal Committee, Hoshiarpur v. Punjab SEB, (2010) 13 SCC 216.

- ↑ C.A. Sulaiman vs. State Bank of Travancore, Alwayee (2006) 6 SCC 392.

- ↑ State Bank of India vs. S.N. Goyal (2008) 8 SCC 9215.

- ↑ Umerkhan v. Bismillabi, (2011) 9 SCC 684.

- ↑ State Bank of India vs. S.N. Goyal (2008) 8 SCC 9215.

- ↑ Raja of Pittapur v. Secretary of State (1929) 56 LA 223.

- ↑ Ram Gopal v. Shamskaton, (1893) ILR 20 Cal 93.

- ↑ Mahesh Chand v. Raj Kumari, AIR 1996 SC 869.

- ↑ Chaya v. Bapusaheb (1994) 2 SCC 41.

- ↑ Gopal v. Hanumant (1882) ILR 6 Bom 107.

- ↑ Chander Kanta Sinha v. Oriental Insurance Co. Lts. (2001) LRI 1251.

- ↑ Gurdev Kaur v. Kaki AIR 2006 SC 1975.

- ↑ Chacko & Anr. v. Mahadevan, (2007) 7 SC 363

- ↑ Section 16(1) of Andhra Pradesh Civil Courts Act, 1972

- ↑ Id.

- ↑ Bombay City Civil (Amendment) Act, 2023, the Amendment enhanced pecuniary jurisdiction from one crore to ten crores, Section 3 of the Bombay City Civil Court Act, 1948 https://www.livelaw.in/pdf_upload/bombay-city-civil-amendment-act-2023-505619.pdf

- ↑ Bombay City Civil Court Act, 1948, Section 15

- ↑ Appeals valued up to ₹20,00,000 (transferred from High Court as per Goa Amendment Act, 2009), Goa Civil Courts Act, 1965, Section 20-A

- ↑ Goa Civil Courts Act, 1965, Section 25; Appeals from orders under special law - To District Court if subject matter is up to ₹10,000

- ↑ Goa Civil Courts Act, 1965, Section 22

- ↑ Goa Civil Courts Act, 1965, Section 25; Appeals from orders under special law - To High Court if subject matter is exceeding ₹10,000

- ↑ Gujarat Civil Courts Act, 2005, Section 15(2)

- ↑ Id.

- ↑ Karnataka Civil Courts Act, 1964, Section 17

- ↑ Karnataka Civil Courts Act, 1964, Section 18

- ↑ Karnataka Civil Courts Act, 1964, Section 19

- ↑ Kerala Civil Courts Act, 1957, Section 13

- ↑ Kerala Civil Courts Act, 1957, Section 12

- ↑ Madhya Pradesh Civil Courts Act, 1958; Section 13

- ↑ Id.

- ↑ Orissa Civil Courts Act, 1984, Section 16(2)(a)

- ↑ Orissa Civil Courts Act, 1984, Section 16(3)

- ↑ Orissa Civil Courts Act, 1984, Section 16(1)(a)

- ↑ Orissa Civil Courts Act, 1984, Section 16(2)(B)

- ↑ Puducherry Civil Courts Act, 1966, Section 9

- ↑ Id.

- ↑ Sikkim Civil Courts Act, Section 18(2)

- ↑ Id.

- ↑ Telangana Civil Courts Act, 1972, Section 17

- ↑ Id.

- ↑ Prasanna, Alok, et al. EFFECTIVE SUPREME COURT: ADDRESSING ISSUES of BACKLOG and REGIONAL DISPARITIES in ACCESS. 2016.

- ↑ “The Pandemic Provides Answers to How the Supreme Court Can Be Taken beyond New Delhi.” Article-14.com, home, 2024, article-14.com/post/the-pandemic-provides-answers-to-how-the-supreme-court-can-be-taken-beyond-new-delhi--6191d28ac710b. Accessed 5 Nov. 2024.

- ↑ Kumar Kartikeya. “It’s Time to Revamp the Structure of the Supreme Court.” The Hindu, 27 Nov. 2023, www.thehindu.com/opinion/op-ed/its-time-to-revamp-the-structure-of-the-supreme-court/article67579914.ece. Accessed 5 Nov. 2024.

- ↑ Id 28

- ↑ Id 28

- ↑ Aishwarya K, and Aishwarya K. “Unraveling Karnataka High Court Appeals: Challenges & Reforms.” Daksh, 29 May 2024, www.dakshindia.org/karnataka-high-court-appeals-challenges-reforms/. Accessed 5 Nov. 2024.