Competition Commission of India

What is the Competition Commission of India?

The Competition Commission of India (CCI) is a statutory body established by the Central Government under the Competition Act, 2002 (‘the Act’).[1] Although the Act came into effect in a staggered manner starting from 2003,[2] it became fully operational only in 2007 .[3] CCI is the national regulator that keeps markets fair by preventing and punishing, as the case may be, anti-competitive conduct, reviewing mergers, and promoting healthy rivalry for the benefit of consumers and businesses. The Competition Act, 2002 tasks it with sustaining competition, protecting consumer interests (see consumer welfare), eliminating practices that harm competition, and ensuring freedom of trade in India.[4][5] The Commission is also required to give opinion on competition issues on a reference received from a statutory authority established under any law and to undertake competition advocacy, create public awareness and impart training on competition issues.[4]

The CCI replaced the Monopolies and Restrictive Trade Practices Commission (MRTP Commission) after the enactment of the Competition Act, 2002. In a number of ways, CCI marked a more open, market-trusting, and competition promoting approach in its transition from the MRTP Commission. Key distinctions include the CCI’s focus on promoting competition and preventing anti-competitive practices, whereas the MRTP Commission focused largely on curbing monopolistic and restrictive trade practices. While MRTP was size/concentration-based (control) and lacked a merger control framework, CCI/Competition Act is conduct-focused (promotion of competition) and includes ex-ante merger review and conduct remedies.

Official definitions of Competition Commission of India

Competition Commission of India as defined in legislation(s)

The Competition Act, 2002

According to section 2(e) of the Competition Act, 2002, Competition Commission of India is the Commission appointed for the purposes of the said Act under section 7(1). Section 7 provides for the establishment of the Commission. The Commission shall be: a body corporate by the name aforesaid having perpetual succession and a common seal with power, subject to the provisions of this Act, to acquire, hold and dispose of property, both movable and immovable, and to contract and shall, by the said name, sue or be sued.[6] The head office of the Commission shall be at such a place as the Government may decide from time to time.[7]

Composition of CCI

The Commission consists of a Chairperson and a minimum of two members.[8] The maximum number of members is six, all of which are appointed by the Central Government.[9] They are appointed on recommendation by a Selection Commission composed of the Chief Justice of India, the Secretary in the Ministry of Corporate Affairs amongst others. The members appointed are required to be person of ability, integrity and standing and who has special knowledge of, and such professional experience of no less than fifteen years in international trade, economics, business, commerce, law, finance, accountancy, management, industry, public affairs or competition matters, including competition law and policy, which in the opinion of the Central Government may be useful for the Commission.[8]

Duties and Functions of the Commission

Section 18 of the Competition Act provides the major duties of CCI, which include:

- eliminate practices having adverse effect on competition

- promote and sustain competition

- protect the interests of consumers

- ensure freedom of trade carried on by other participants, in markets in India

In addition to these duties, the CCI also acts towards competition advocacy in India and also undertakes its own market studies on different aspects of competition in various sectors in India. CCI has previously undertaken market studies on the mining sector and cab aggregator industries amongst others, which are publicly accessible on the CCI website.[10][11]

Powers of the Commission

- The Commission has the power to inquire into certain agreements and the dominant position of enterprise and any alleged contravention of the provisions contained in section 3(1) and section 4(1).[12] Section 3(1) prohibits any enterprise from entering into any agreement which causes or is likely to cause an appreciable adverse effect on competition within India. Section 4(1) prohibits any enterprise from abusing its dominant position.

- The Commission shall, while determining whether an agreement has an appreciable adverse effect on competition under section 3, have due regard to factors such as- a) creation of barriers to new entrants in the relevant market; (b) driving existing competitors out of the relevant market; (c) foreclosure of competition by hindering entry into the relevant market.[13]

- The Commission shall, while inquiring whether an enterprise enjoys a dominant position or not under section 4, have due regard to factors such as:- (a) market share of the enterprise; (b) size and resources of the enterprise; (c) size and importance of the competitors.[14]

- The Commission may, upon its own knowledge or information relating to acquisition referred to in Section 5, inquire into whether such a combination has caused or is likely to cause an appreciable adverse effect on competition in India.[15]

- Where in the course of a proceeding before any statutory authority an issue is raised by any party that any decision which such statutory authority has taken or proposes to take is or would be, contrary to any of the provisions of this Act, then such statutory authority may make a reference in respect of such issue to the Commission. On receipt of a reference, the Commission shall give its opinion, within sixty days of receipt of such reference, to such statutory authority.[16]

- On receipt of a reference from the Central Government or a State Government or a statutory authority or on its own knowledge or information received under section 19, if the Commission is of the opinion that there exists a prima facie case, it shall direct the Director General to cause an investigation to be made into the matter.[17]

- Where after inquiry the Commission finds that any agreement referred to in section 3 or action of an enterprise in a dominant position, is in contravention of section 3 or section 4, as the case may be, it may pass orders such as imposition of penalty or direction to discontinue such agreement.[18]

- The Commission also has powers to direct division of an enterprise enjoying dominant position,[19] conduct investigation of combinations,[20] issue interim orders, and power to regulate its own procedure.[21]

- The Commission shall have, for the purposes of discharging its functions under this Act, the same powers as are vested in a Civil Court under the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 (5 of 1908), while trying a suit.[22]

- The Commission may direct the Director General to assist the Commission in investigating into any contravention of the provisions of the Act or any rules or regulations made thereunder. [23]

- The Chairperson shall have the powers of general superintendence, direction and control in respect of all administrative matters of the Commission. [23]

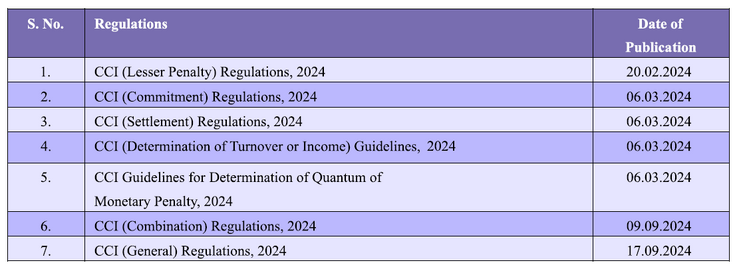

The commission, in exercise of its rule making powers, has notified a number of rules and regulations over the years in response to various amendments, changing market dynamics, and in pursuance of its objectives. In 2024 alone, as the MCA Annual Report indicates, the CCI notified seven different regulations. (See Table below)

Investigations and Inquiries Ordered by the Commission

The Competition Commission of India (CCI) in its Annual report 2023-24 investigates potential violations of Sections 3 (anti-competitive agreements), 4 (abuse of dominant position), and 42 (non-compliance) of the Competition Act. These investigations may be initiated Suo motu (on its own motion), based on information from individuals, consumers, or trade associations under Section 19(1)(a) and on a reference from the Central/State Government or a statutory authority under Section 19(1)(b). After examining the complaint, the Commission determines whether there is a prima facie case. If yes, it orders an investigation by the Director General under Section 26(1) else, it closes the case under Section 26(2).

Between May 20, 2009, to November 30, 2024, a total of 1,300 cases were registered under Section 19 of the Competition Act, 2002. Of these, the Commission has disposed of 1,163 cases. In addition, three cases were quashed by the Hon'ble Supreme Court and in two cases order for investigation has been set aside by the Hon'ble Delhi High Court. Furthermore, 516 cases were referred to DG for investigation including those cases in which orders under Section 26(1) have not been passed but have been clubbed with similar matters and directed by various courts. DG has submitted investigation report in respect of 484 cases. The investigation is underway in various other cases.[24]

Appeals

Competition Appellate Tribunal (COMPAT) was constituted following the passage of the Competition (Amendment) Act, 2007. It was established on 15th May, 2009, authorized to hear appeals from the orders of CCI and pass relevant judgments. It amended the Competition Act by deleting Section 40 and introducing Chapter VIIIA titled “Appellate Tribunal''. Prior to the amendment, any person aggrieved by any decision or order of the Competition Commission of India would have to directly file an appeal with the Supreme Court asking for necessary relief. It ceased to be in effect following the amendments made by section 171 of the Finance Act, 2017 which designated the National Company Law Appellate Tribunal (NCLAT), constituted under section 410 of the Companies Act, 2013, as the appellate authority for CCI orders. Post-amendment, according to Section 53A, The National Company Law Appellate Tribunal shall hear and dispose of appeals against any direction issued or decision made or order passed by CCI.[25] Some of the recent literature, however, point out that NCLAT might not be well-equipped to handle the appellate jurisdiction over the CCI, owing particularly to its lack of relevant technical expertise, among other factors.[26][27]

The Central Government or any State Government or the Commission or any statutory authority or any local authority or any enterprise or any person aggrieved by any decision or order of the Appellate Tribunal may file an appeal to the Supreme Court within sixty days from the date of communication of the decision or order of the Appellate Tribunal to them.[28]

Recently, the Competition Law Review Committee[29] has made recommendations regarding the functioning and institutional structure of the CCI and bodies related to the Competition Act. The committee was set up on 1st October, 2018 to review the Competition Act and Rules and Regulations framed thereunder. The Committee has been tasked with the responsibility to review and recommend a robust competition regime, by taking the inputs of key stakeholders, and suggesting changes in both the substantive and procedural aspects of the law. Some of its recommendations with respect to the CCI include creation of a governing body and subsuming Director General within the CCI. The Committee recommended that the Act be amended to provide for a governing body, to strengthen the accountability of the CCI. The governing body will consist of a Chairperson, six whole time members, and six part-time members. It will perform quasi-legislative functions, drive policy decisions, and perform a supervisory role.

Competition Commission of India as defined in official government report(s)

Ministry of Corporate Affairs, Annual Report (2024-25)

The annual reports of the Ministry of Corporate Affairs, Government of India reports the updates regarding competition rulemaking, amendments, enforcements, and adjudications on an annual basis, the latest one being the 2024-25 report. The Report gives a synoptic view of the organizational structure, functions and activities of the Ministry undertaken during the previous financial year and the first three quarters of the current financial year.[30] The report covers activities related to the CCI from pages 31 to 36, and covers the recent regulations notified by the Commission, enforcement activities, merger control activities, various initiatives, and advocacy activities.

Report of the Standing Committee on Finance (2024-25)

The 25th Report of the Standing Committee on Finance (2024-25), presented to the 18th Lok Sabha in August 2025 under the chairpersonship of Shri Bhartruhari Mahtab examines the evolving role of the Competition Commission of India in light of structural changes in the economy, especially digital markets. The report defines the CCI as a statutory regulator under the Competition Act 2002 tasked with maintaining fair and efficient markets, preventing anti-competitive conduct, and safeguarding consumer interest. It situates the CCI within India's shift from a controlled economy to a market-based one and notes that while markets generate dynamism, they are not self-correcting, which justifies a capable competition authority.

The Committee presents the CCI as an institution adapting to complex digital market structures shaped by network effects, data advantages, platform ecosystems, and zero-price services. It welcomes recent reforms, including deal-value thresholds, settlement and commitment mechanisms, revised penalty tools, and creation of a Digital Markets Division. The report ultimately portrays the CCI as a regulator in transition, one that must strengthen domain expertise and analytical capacity to address digital dominance while continuing to uphold competitive freedom, innovation, and consumer welfare.[31]

Report of the Committee on Digital Competition Law

The Committee on Digital Competition Law has also released a Report of the Committee on Digital Competition Law[32] in 2024, recommending an ex-ante competition framework for digital markets in India. The Competition Act as well as the Commission in antitrust matters adopt an ex post approach (wherein regulatory intervention happens after the occurrence of an anti-competitive conduct) in prohibiting anti-competitive agreements (Section 3) and abuse of dominance (Section 4). The committee strongly advised that the CCI must strengthen the capacity of its Digital Markets and Data Unit with experts from the field of technology to keep pace with the rapid evolution of digital markets. Further, the Committee recommended instituting a separate bench within the National Company Law Appellate Tribunal to ensure timely disposal of appeals filed against the CCI’s orders, particularly those relating to digital markets.

Report of the Standing Committee on Finance (2022-23)

The sixtieth report of the Standing Committee on Finance (2022-23), seventeenth Lok Sabha, highlights the actions taken by the Government on the observations recommendations contained in the fifty-third report on anti-competitive practices by Big Tech companies. In addition to the role of other stakeholders, the report highlights the role of CCI not only as a regulator but also as a stakeholder.

Report of the Competition Law Review Committee

The 2019 report by the Competition Law Review Committee places CCI as an expert-regulator established under the Competition Act, 2002, with investigatory, regulatory, adjudicatory and advocacy functions. The Committee notes that while the CCI has discharged its mandate, the evolving complexity of markets, particularly new age technology-based models, requires structural reforms.[33]

OECD’s Annual Report on Competition Policy Developments in India

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development releases an annual report[34] on the work carried out by CCI. It traces changes to competition laws and policies, proposed or adopted and enforcement of competition laws. It highlights important decisions and orders of CCI under various sections of the Act. In its 2022 report, it also compiled data to record sector-wise distribution of combinations notices of mergers received by CCI. The data available is as follows:

Appearance in official databases

CCI’s Annual Reports

The CCI releases its annual report[35] to share a comprehensive review of all activities undertaken by or brought before CCI. These reports contain information such as landmark decisions of the Commission, the number of complaints filed, and actions undertaken by the CCI including notices issued and penalties imposed. It also has details of budgets and number of selections, vacancies and recruitments.

Investigations and Inquiries Ordered by the Commission

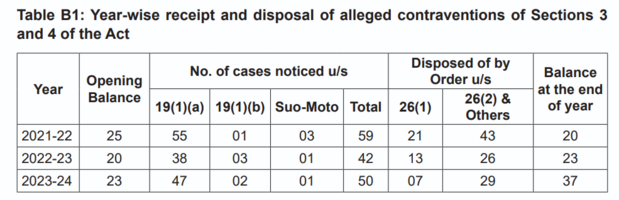

Details of investigation and inquiries ordered and their outcomes are summarized in Table B1 below:[36]

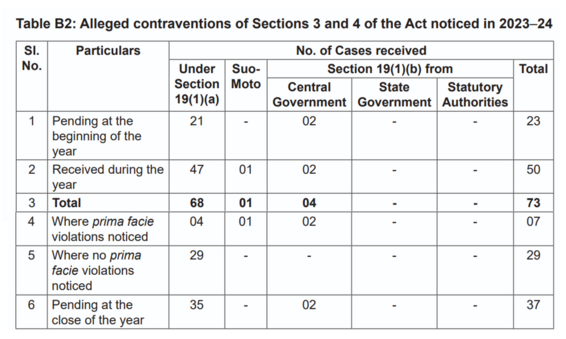

Table B2 of the CCI Annual Report 2023–24 highlights the Commission’s scrutiny of alleged contraventions of Sections 3 and 4 of the Competition Act. It outlines how cases were initiated, whether based on information from individuals or associations, Suo moto action, or references from the government, and tracks their progression through the year. The table reflects the Commission’s process of examining cases for prima facie violations, closing those without merit, and carrying unresolved matters forward. Overall, it showcases the CCI’s enforcement activity and its commitment to addressing anti-competitive practices and abuse of dominant position in the market.[36]

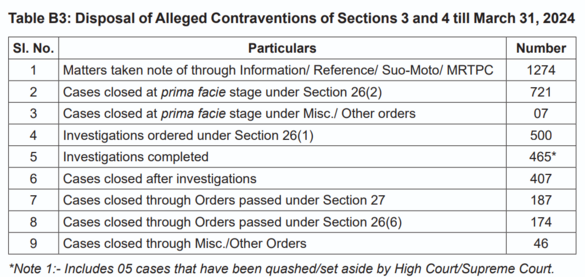

This section outlines that the Director General investigates alleged violations of the Competition Act when directed by the Commission. Based on the investigation and fair hearings, the Commission issues final orders. Table B3 presents the disposal of such cases under Sections 3 and 4 as of March 31, 2024.[36]

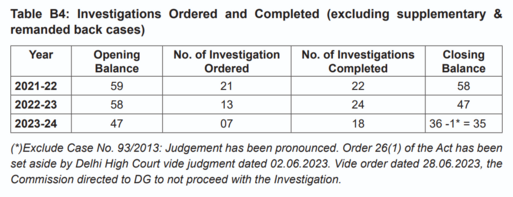

Year-wise details of investigations Ordered by the Commission and their disposal by the DG are presented in Table B4.[36]

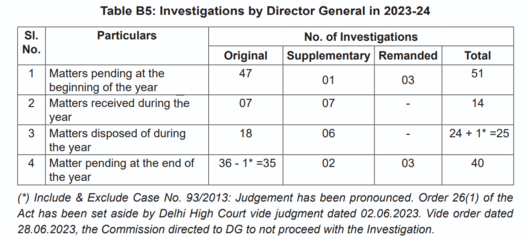

In some cases, after receipt of the DG report, if the Commission is of the opinion that further investigation is called for, it may direct the DG to do so and submit a supplementary report on specific issues. Details of investigations by the DG in 2023–24 are given in Table B5.[36]

Appeals

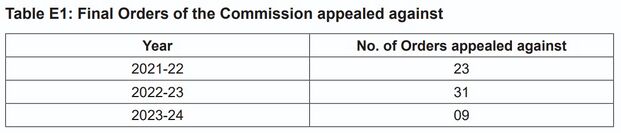

This section explains the appellate process under the Competition Act. Any person aggrieved by specific orders or decisions of the Commission can appeal to the National Company Law Appellate Tribunal (NCLAT) under Section 53B. This review by the NCLAT ensures fairness and accountability in the Commission’s functioning. Further, appeals against NCLAT orders can be made to the Supreme Court under Section 53T. The incidence of Orders of the Commission being appealed against is presented in Table E1.[36]

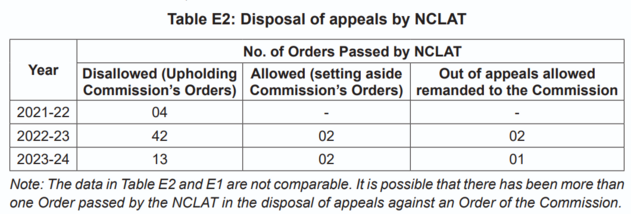

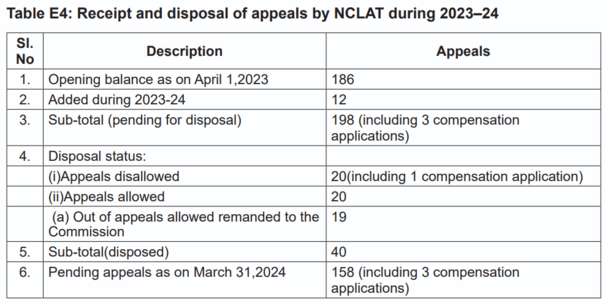

The disposal of appeals by the NCLAT over the year is presented in Table E2. It is observed that during 2023-24, the NCLAT has disposed of 40 appeals against 15 Orders of the Commission till March 31, 2024.[36]

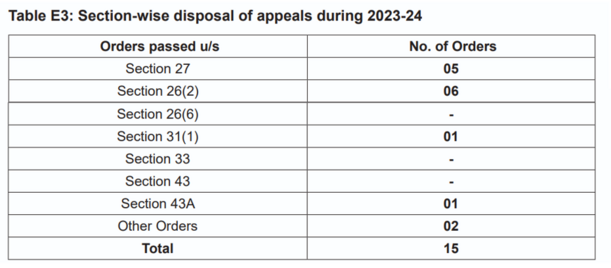

Table E3 presents Section-wise details of disposal of appeals during 2023–24[36]

Details of disposal of appeals by the NCLAT during 2023–24 are presented in Table E4. The NCLAT disallowed 20 appeals (including 1 compensation application) in 13 CCI Orders.[36]

Matters Received Regarding Combination

This section outlines the legal framework for regulating combinations (mergers, acquisitions, and amalgamations) under the Competition Act, in effect since June 1, 2011. It explains that combinations meeting certain asset or turnover thresholds must be notified to the CCI for competition analysis. Although the 2023 Amendment introduced a deal value threshold, it is yet to be notified. The Act prohibits combinations likely to cause an appreciable adverse effect on competition (AAEC), but allows modifications to address such concerns. The Commission can also initiate inquiries Suo moto. The Green Channel route, introduced in 2019 for automatic approval of eligible combinations, continues to be used, with 100 filings made under it so far.

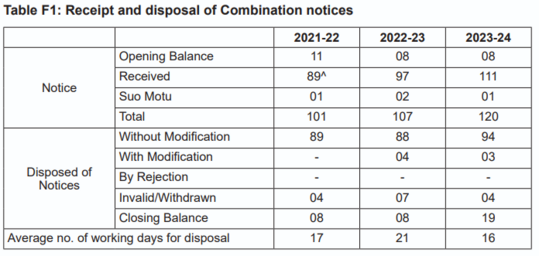

Table No. F1 presents the details of notices received and disposed of till March, 2024[36]

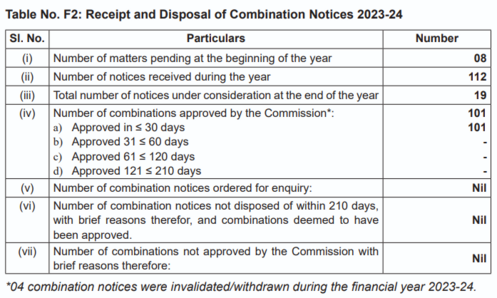

Details regarding the notices received and disposed of in 2023-24 are presented in Table No. F2.

Research engaging with CCI

Research engaging with the CCI portrays it as an expert regulator steadily maturing in its enforcement role while grappling with economic-analysis capacity, institutional design, and digital-market complexity.

Research on the evolution of CCI's enforcement

Merger Control in India by G Chhabra & S Nathani (2015)

Merger Control in India: Is There A Long Road Ahead by Gauri Chhabra and Suhail Nathani in World Competition charts the evolution of the post-2011 merger regime,[37] and discusses the role of the Competition Commission of India in its evolution. It notes that while the Commission has made significant inroads in streamlining and simplifying the merger control process in India, there remain considerable uncertainties and complexities in relation to the application of merger control provisions in India.

Competition law enforcement in India: issues and challenges by DK Sikri (2017)

This article by ex-CCI chairperson DK Sikri, which also served as the opening statement for the issue on Indian competition law by the Journal of Antitrust Enforcement, stresses that CCI’s institutional evolution has been shaped by the legacy of the MRTP era and the transition to a competition-promoting regime, with early years marked by capacity-building, nascent jurisprudence, and significant delays due to appellate bottlenecks and High Court interventions.[38]

Anti-cartel enforcement in India by A Bhattacharjea & O De (2017)

This paper by Aditya Bhattacharjea and Oindrila De in the Journal of Antitrust Enforcement tracks the foundational enforcement against cartels[39] including the cement cartel case, and highlights deterrence potential of the Commission while also emphasising difficulties in evidence and penalty calibration.

Patents and Competition Law in India by Y Pai and N Daryanani (2017)

This paper titled Patents and competition law in India: CCI's reductionist approach in evaluating competitive harm by Yogesh Pai and Nitesh Daryanani in the Journal of Antitrust Enforcement highlights the reductionist approach taken by the Competition Commission of India in regulating the concerns of abuse of dominance in the IP sector, including patents. It warns that reductionist antitrust reasoning in patent disputes may chill innovation, urging calibrated, dynamic-efficiency-oriented standards.[40]

Vertical restraints under Indian Competition Law by V Kathuria (2022)

Vertical restraints under Indian Competition Law: whither law and economics by Vikas Kathuria notes uncertainty in standards, timelines, and effects-based reasoning.[41] By highlighting legal ambiguities in the interpretation of the legislation, the incoherence of the economic analysis, and a visible overreliance on the EU jurisprudence without conforming to the legislative scheme of the Indian Competition Act, the author draws out lessons for the Commission for effect-based analysis under Indian competition law.

State of Tribunals Report by Daksh (2025)

The State of Tribunals in India is a 2025 report by Daksh attempting to map, analyse, and evaluate the functioning of India's tribunal ecosystem, with a focus on commercial tribunals. The report covers a detailed review of NCLAT's time as the competition law appellate tribunal, and highlights various issues and challenges therein. Among other issues, it highlights NCLAT's emphasis on procedure over substance, lack of subject-matter expertise and composition challenges, procedural bottlenecks, prolonged timelines etc. The key recommendations include remand over dismissal on procedural issues, capacity building and structural reforms, dedicated bench and institutional support infrastructure, long-term institutional review etc.

Research on reforms and initiatives

Recalibrating India’s competition law by R Kaur (2025)

Ravneet Kaur’s article Recalibrating India’s Competition Law: A New Era of Regulation and Enforcement traces how the 2023 amendments to the Competition Act transformed India’s competition regime into a more agile and forward-looking framework. It outlines key reforms such as the introduction of a deal value threshold for merger control, a broader definition of 'control', shorter approval timelines, and stricter penalties. Antitrust enforcement has been modernized through mechanisms like settlement and commitment, leniency plus, and global turnover based penalties, while the scope of anti-competitive agreements now extends to hub-and-spoke cartels. Complementary regulations issued in 2024–25 strengthen transparency, proportionality, and predictability in penalty determination and enforcement.[42]

Market studies by CCI

The Commission uses market studies as a key research tool to better understand competitive conditions across various sectors. These studies analyze how particular markets function, the regulatory frameworks that govern them, and the implications for competition. They also assess patterns of consumer and business behavior relevant to market dynamics. The insights generated from these market studies enable the CCI to engage in competition advocacy by making evidence-based recommendations to governments, sector regulators, businesses, and business associations. This proactive approach helps in identifying competition issues and shaping regulatory and policy interventions to foster competitive markets in India. CCI’s market studies are accessible through a dedicated archive on its website, showcasing research projects focused on different sectors.

Journal on Competition Law and Policy by CCI

The Competition Commission of India (CCI) Journal on Competition Law and Policy is a biannual publication aimed at fostering rigorous interdisciplinary research in competition law, economics, and related fields. Established by CCI, the journal seeks to stimulate informed debate on contemporary competition issues in the Indian context and apply research insights to enforcement and advocacy efforts. It welcomes original high-quality research papers, case studies, and book reviews on themes such as cartels, market power, mergers, platform markets, intellectual property rights, and recent developments in competition policy.

Research on jurisdiction competition

A small but sharp body of scholarship now examines the emerging competition among various sectoral regulators for India's competition jurisprudence, where institutional turf and judicial deference shape the trajectory of antitrust doctrine.

Competition for India’s antitrust jurisdiction by M Singh (2023)

Madhavi Singh’s article, The Competition for India’s Antitrust Jurisdiction: Competition Commission versus Sectoral Regulators examines how Indian courts have progressively curtailed the Commission's authority by requiring it to defer to sectoral regulators before exercising its own jurisdiction. The paper traces the statutory framework and landmark judgments such as Ericsson v CCI and CCI v Bharti Airtel, arguing that the judiciary’s deference to sectoral expertise has effectively weakened the CCI’s mandate and delayed enforcement. Singh contends that the rationale for deferral fails under scrutiny, as the CCI’s ex post competition oversight is distinct from sectoral regulators’ ex ante supervision. The author highlights inconsistencies and inefficiencies in the judicial test for jurisdictional overlap, warning that such deferrals may de facto divest the CCI of its powers.[43]

International Experiences

Competition regulators have become central to the architecture as well as efficient functioning of modern market economies.[44] As markets grow more data driven and networked, the task of safeguarding competitive conditions has moved from the periphery of policy to a core governance function.[45] Most major jurisdictions now maintain specialised competition authorities to oversee market conduct, address anti-competitive practices, and preserve contestability. The United States and the European Union have long served as reference points, given the depth of their enforcement histories and the richness of their jurisprudence. Yet the experience is increasingly plural. Countries adapt competition principles to their own policy trajectories, industrial priorities, and developmental contexts, which leads to variation in institutional design and enforcement philosophy. Scholarship has noted this pattern of convergence in aims combined with divergence in methods.[46] The Competition Commission of India operates within this wider global field, learning from established regimes while shaping approaches that reflect national economic priorities.

USA

In the US, two federal agencies are primarily responsible for enforcing antitrust laws: the Antitrust Division of the US Department of Justice (DoJ) and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC). The DoJ is part of the executive branch of the government, while the FTC is an independent administrative agency similar to the Competition Commission of India (CCI). The Sherman Act, the oldest federal antitrust statute enacted in 1890, addresses anti-competitive agreements and monopolistic practices. The Clayton Act of 1914 deals with specific business practices, including mergers, price discrimination, tying arrangements, and exclusive supply agreements. Both the DoJ and FTC enforce the Sherman Act and the Clayton Act independently, but the DoJ has exclusive authority to prosecute criminal violations. Additionally, most states have their own antitrust laws enforced by state attorneys general. However, the majority of antitrust litigation in the US comes from private enforcement, where competitors, suppliers, and customers seek damages for injuries caused by anti-competitive conduct.

European Union

The competition law of the European Union[47] is detailed in Articles 101 to 109 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU). This treaty covers prohibitions on agreements that restrict competition, abuse of dominant positions, and state aid. In addition to the main treaty, various rules, guidelines, and notices have been issued to regulate areas such as mergers and concentrations.[48] The European Commission is the primary enforcer of these rules, responsible for tasks like fact-finding, taking action against infringements, and imposing penalties. Challenges to Commission decisions in competition cases are first brought before the General Court,[49] with appeals heard by the Court of Justice.[50] EU competition law is often applied by the Commission and EU courts with consideration for the integration of the single European market. Member states also have their own domestic competition laws, modeled after Articles 101 and 102 of the TFEU, and enforcement activities are conducted by the 27 National Competition Authorities.[51]

Data Challenges

Serious research on CCI is constrained by multiple recurring gaps. First, primary filings, DG reports, and evidence are often unavailable or heavily redacted because of the CCI's confidentiality regime,[52] which the Commission itself had flagged for review, limiting reproducibility and external auditing of decisions. Second, there is no unified, machine-readable case-level database that links CCI matters with subsequent appellate outcomes in NCLAT and the Supreme Court; orders are scattered across websites and PDFs with inconsistent metadata. Comparative open-data work in Indian justice reform shows why standardised, API-friendly formats and dashboards matter for transparency and research use.[53] Third, appellate churn and stays complicate impact evaluation. The coherence and capacity of NCLAT as an appellate tribunal also introduces further delays, uncertainties, and nuances into the already complex competition enforcement process.[26] As pointed out by the 25th Report of the Standing Committee on Finance, as of April 30, 2025, out of the total imposed penalty of Rs 20,350 crore by CCI, Rs 18,512 crore has been stayed or dismissed by the Appellate Courts.[31] Fourth, institutional capacity and coordination issues create information asymmetries. The Committee records high vacancy levels, funding constraints, and calls for formal protocols with sectoral regulators and for a national competition policy, all of which bear directly on data flows, timeliness of disclosures, and consistency of market studies.[31]

References

- ↑ Section 7, Competition Act, 2002, Available at: https://www.cci.gov.in/images/legalframeworkact/en/the-competition-act-20021652103427.pdf

- ↑ See Gazette Notification S.O. 715(E) dated 19th June, 2003. Available at: https://www.mca.gov.in/Ministry/notification/Notifications_2003/noti_19062003.html

- ↑ INTRODUCTION TO COMPETITION LAW (Part 1- Basic Introduction), CCI, Available at:http://164.100.58.95/sites/default/files/advocacy_booklet_document/CCI%20Basic%20Introduction_0.pdf

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 About Us, CCI, Available at: https://www.cci.gov.in/about-us#:~:text=Competition%20Commission%20of%20India,-The%20objectives%20of&text=It%20is%20the%20duty%20of,in%20the%20markets%20of%20India.

- ↑ Section 18, Competition Act, 2002, Available at: https://www.cci.gov.in/images/legalframeworkact/en/the-competition-act-20021652103427.pdf

- ↑ Section 7(2), Competition Act, 2002, Available at:https://www.cci.gov.in/images/legalframeworkact/en/the-competition-act-20021652103427.pdf

- ↑ Section 7(3), Competition Act, 2002, Available at: https://www.cci.gov.in/images/legalframeworkact/en/the-competition-act-20021652103427.pdf

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Section 8, Competition Act 2002, Available at: https://www.cci.gov.in/images/legalframeworkact/en/the-competition-act-20021652103427.pdf

- ↑ Section 9, Competition Act, 2002, available at: https://www.cci.gov.in/images/legalframeworkact/en/the-competition-act-20021652103427.pdf

- ↑ Market Studies and Research, CCI. Available at: https://www.cci.gov.in/economics-research/market-studies

- ↑ Market Study Report on Dynamics of Competition in the Mining Sector in India with a Focus on Iron Ore, CCI, Available at: https://www.cci.gov.in/economics-research/market-studies/details/44/0

- ↑ Section 19, Competition Act 2002, Available at: https://www.cci.gov.in/images/legalframeworkact/en/the-competition-act-20021652103427.pdf

- ↑ Section 19(3), Competition Act 2002, Available at: https://www.cci.gov.in/images/legalframeworkact/en/the-competition-act-20021652103427.pdf

- ↑ Section 19(4), Competition Act 2002, Available at: https://www.cci.gov.in/images/legalframeworkact/en/the-competition-act-20021652103427.pdf

- ↑ Section 20, Competition Act, 2002, Available at: https://www.cci.gov.in/images/legalframeworkact/en/the-competition-act-20021652103427.pdf

- ↑ Section 21, Competition Act, 2002, Available at: https://www.cci.gov.in/images/legalframeworkact/en/the-competition-act-20021652103427.pdf

- ↑ Section 26, Competition Act, 2002. Available at: https://www.cci.gov.in/images/legalframeworkact/en/the-competition-act-20021652103427.pdf

- ↑ Section 27, Competition Act, 2002, Available at: https://www.cci.gov.in/images/legalframeworkact/en/the-competition-act-20021652103427.pdf

- ↑ Section 28, Competition Act, 2002, Available at: https://www.cci.gov.in/images/legalframeworkact/en/the-competition-act-20021652103427.pdf

- ↑ Section 29, Competition Act, 2002, Available at: https://www.cci.gov.in/images/legalframeworkact/en/the-competition-act-20021652103427.pdf

- ↑ Section 36(1), Competition Act, 2002, Available at: https://www.cci.gov.in/images/legalframeworkact/en/the-competition-act-20021652103427.pdf

- ↑ Section 36(2), Competition Act, 2002, Available at: https://www.cci.gov.in/images/legalframeworkact/en/the-competition-act-20021652103427.pdf

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Section 13, Competition Act, 2002, Available at: https://www.cci.gov.in/images/legalframeworkact/en/the-competition-act-20021652103427.pdf

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 See Ministry of Corporate Affairs, Govt. of India, Annual Report 2024-25, page 32.

- ↑ Section 53A, Competition Act, 2002, Available at: https://www.cci.gov.in/images/legalframeworkact/en/the-competition-act-20021652103427.pdf

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 See The State of Tribunals Report, Daksh (September 2025). Available at: https://www.dakshindia.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/State-of-Tribunals-PDF-Digital.pdf

- ↑ Analysis of NCLAT’s Functioning as Competition Law Appellate Tribunal, N S Suhag et al (2021). Available at: http://doi.org/10.54425/ccijoclp.v2.36

- ↑ Section 53T, Competition Act, 2002, Available at: https://www.cci.gov.in/images/legalframeworkact/en/the-competition-act-20021652103427.pdf

- ↑ Report Of Competition Law Review Committee July, 2019, Available at: https://www.ies.gov.in/pdfs/Report-Competition-CLRC.pdf

- ↑ See Annual Reports, MCA, GoI. Available at: https://www.mca.gov.in/content/mca/global/en/data-and-reports/reports/annual-reports/annual-report.html

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 25th Report of the Standing Committee on Finance, 18th Lok Sabha (August 2025). Available at: https://sansad.in/getFile/lsscommittee/Finance/18_Finance_25.pdf?source=loksabhadocs

- ↑ REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE ON DIGITAL COMPETITION LAW – 2024 New Delhi, 27 February, 2024, Available At: https://www.mca.gov.in/bin/dms/getdocument?mds=gzGtvSkE3zIVhAuBe2pbow%253D%253D&type=open

- ↑ Report of Competition Law Review Committee (2019). Available at: https://www.ies.gov.in/pdfs/Report-Competition-CLRC.pdf

- ↑ Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Annual Report on Competition Policy Developments in India (2022), Available At:https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/COMP/AR(2023)45/en/pdf

- ↑ CCI's Annual Reports, Available at: https://www.cci.gov.in/annual-report

- ↑ 36.00 36.01 36.02 36.03 36.04 36.05 36.06 36.07 36.08 36.09 Annual Report 2023-24, CCI, Available at: https://www.cci.gov.in/annual-report

- ↑ G Chhabra & S Nathani, Merger Control in India: Is There A Long Road Ahead?, 38 World Competition 281 (2015). https://doi.org/10.54648/woco2015019

- ↑ DK Sikri, Competition law enforcement in India: issues and challenges: Opening statement from the Competition Commission of India, 5 JAE 163 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1093/jaenfo/jnx008

- ↑ A Bhattacharjea & O De, Anti-cartel enforcement in India, 5 JAE 166 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1093/jaenfo/jnx001

- ↑ Y Pai & N Daryanani, Patents and competition law in India: CCI’s reductionist approach in evaluating competitive harm, 5 JAE 299 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1093/jaenfo/jnx004

- ↑ V Kathuria, Vertical restraints under Indian Competition Law: whither law and economics, 10 JAE 194 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1093/jaenfo/jnab002

- ↑ R Kaur, Recalibrating India’s competition law: a new era of regulation and enforcement, JAE (2025). https://doi.org/10.1093/jaenfo/jnaf027

- ↑ M Singh, The competition for India’s antitrust jurisdiction: Competition Commission versus sectoral regulators, 11 JAE 91 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1093/jaenfo/jnac012

- ↑ G Nicoletti, C Vitale, & C Abate, Competition, regulation, and growth in a digitized world (OECD Economics Department Working Papers, 2023). https://doi.org/10.1787/1b143a37-en

- ↑ T Raychaudhuri & R Chandrashekhar, The Growing Necessity of Interim Measures to Preserve Competition in Rapidly Changing Digital Markets, 17 IJLT 3 (2021). http://doi.org/10.55496/EGKA1263

- ↑ T K Cheng, Competition Law in Developing Countries (OUP, 2020). https://doi.org/10.1093/law-ocl/9780198862697.001.0001

- ↑ Consolidated versions of the Treaty on European Union and the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union 2012/C 326/01, Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A12012E%2FTXT

- ↑ Eurpoean Commission, Departments and executive agencies, Competition, Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/info/departments/competition_en

- ↑ Court of Justice of the European Union, General Court, Available at: https://curia.europa.eu/jcms/jcms/Jo2_7033/en/

- ↑ Court of Justice of the European Union, Court of Justice, Available at: https://curia.europa.eu/jcms/jcms/Jo2_7024/en/

- ↑ European Commission, Antitrust & Cartels, European Competition Network, National Competition Authorities, Available at:https://ec.europa.eu/competition-policy/antitrust/national-competition-authorities_en

- ↑ See the earlier regime at Regulation 35, CCI General Regulations, 2009. Available at: https://www.cci.gov.in/images/legalframeworkregulation/en/cci-general-regulations-20091652176202.pdf However, the regime now stands updated under Regulation 36, Competition Commission of India (General) Regulations, 2024. Available at: https://cci.gov.in/images/stakeholderstopicsconsultations/en/gazette-notification-published-on-17-sep-2024-regarding-the-competition-commission-of-india-gene1726597052.pdf

- ↑ See Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy, Open Courts in the Digital Age: A Prescription for an Open Data Policy (2019). Available at:https://vidhilegalpolicy.in/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/OpenCourts_digital16dec.pdf See also Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy, Implement India (2024). Available at: https://vidhilegalpolicy.in/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Implement-India-1.pdf