Death Penalty

What is 'Death Penalty'

The death penalty refers to the legal process by which a person is put to death by the state as punishment for a serious crime. It represents the most severe form of punishment prescribed by law, typically reserved for the gravest offenses such as murder, terrorism, or treason. It is distinct from extrajudicial killings, which occur without judicial oversight or due process. The term “capital punishment” is often used interchangeably with “death penalty”; however, technically, the former refers to the actual execution, while the latter denotes the legal sentence itself. In the Indian context, capital punishment remains the highest form of legal penalty under the country’s primary criminal legislation—the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (previously the Indian Penal Code)—and certain special laws. Executions in India are primarily carried out by hanging.

Official Definition of ‘Death Penalty’

‘Death Penalty’ as Defined in Legislation(s)

There is no single, codified definition of capital punishment or death penalty under any Indian statute. However, the term is implicitly recognized as the sentence of death imposed by a competent court of law under various penal provisions. In legislative usage, the expression “punishable with death” or “liable to be punished with death” signifies the imposition of the death penalty as an authorized form of punishment under Indian criminal law.

The Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023 (which replaced the Indian Penal Code, 1860) retains capital punishment as the highest form of penal sanction. Various provisions employ the phrase “punishable with death” to prescribe it as a potential punishment for crimes of extreme gravity, such as murder, terrorism, or aggravated sexual violence.

Similarly, several special statutes, such as the Army Act, 1950, The Commission of Sati (Prevention) Act, 1987, and the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act, 1985, also authorize the death penalty for specific offences, thereby reinforcing its continued legal recognition within India’s criminal justice framework.

Legal Provision(s) Relating to the ‘Death Penalty’

(A) Substantive Legal Provisions:

Under the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023,[1] the following sections prescribe the death penalty as a punishment for specific offences of exceptional gravity:

| Section (BNS) | Nature of Offence |

|---|---|

| § 65(2) | Rape of a child below 12 years of age |

| § 66 | Rape causing death or persistent vegetative state |

| § 70(2) | Gang rape of a child under 18 years of age |

| § 71 | Repeat offences in the context of rape |

| § 103(1) | Murder |

| § 103(2) | Lynching resulting in death |

| § 104 | Murder by a life convict |

| § 107 | Abetment of suicide of a child or person of unsound mind |

| § 109(2) | Attempt to murder by a life convict |

| § 111(2)(a) | Organized crime resulting in death |

| § 113(2)(a) | Terrorism resulting in death |

| § 140(2) | Kidnapping or abduction for ransom or murder |

| § 147 | Treason against the Government of India |

| § 160 | Abetment of mutiny, if mutiny is committed |

| § 230(2) | Fabricating false evidence leading to wrongful execution |

| § 232(2) | Threatening to give false evidence resulting in execution of an innocent person |

| § 310(3) | Dacoity or banditry resulting in death (felony murder) |

Comparable provisions existed in the Indian Penal Code, 1860,[2] under sections such as §§ 120B(1), 121, 132, 194, 302, 305, 307 (2nd para), 364A, 376A, 376AB, 376DB, 376E, and 396, which have now been consolidated and restructured under the BNS.

(B) Death Penalty under Special Laws:

Death Penalty is also authorized under numerous other statutes, including but not limited to:

- Army Act, 1950[3] (e.g., §§ 34, 37, 38) — offences relating to mutiny, desertion, and acts against the enemy.

- The Commission of Sati (Prevention) Act, 1987,[4] § 4(1) — abetment of sati.

- The Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act, 1985,[5] § 31A(1) — repeat offences involving commercial quantities.

- The Defence of India Act, 1971,[6] § 5 — acts intended to wage war or aid external aggression.

- The Maharashtra Control of Organised Crime Act, 1999[7] and The Karnataka Control of Organised Crime Act, 2000,[8] § 3(1)(i) — organized crime resulting in death.

- The Geneva Convention Act, 1960,[9] § 3 — grave breaches of international humanitarian obligations.

(C) Procedural Provisions under the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023 (BNSS):

The BNSS, 2023[10] outlines procedural safeguards and mechanisms governing the imposition and execution of the death penalty.

- § 392–394 BNSS (analogous to §§ 366–371 CrPC) mandate confirmation of death sentences by the High Court.

- § 472 BNSS governs mercy petitions, allowing the condemned person or their relatives to petition the Governor and the President within prescribed timelines.

- § 474 BNSS authorizes suspension or remission of sentences by the appropriate government.

(D) Categories of Persons Exempted from Capital Punishment

Certain categories of individuals are exempted from the imposition or execution of the death penalty under Indian law and judicial interpretation. These are as follows:

- Juveniles: Under Section 21 of the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015,[11] no person who was under 18 years of age at the time of commission of the offence shall be sentenced to death.

- Persons with Mental Illness: In Shatrughan Chauhan v. Union of India (2014), the Supreme Court held (paras 79–87) that executing prisoners with mental illness or insanity would violate Articles 21 and 14 of the Constitution. The Court emphasised that mental illness impairs comprehension and responsibility, thereby rendering the execution unconstitutional.

Term as Defined in International Instrument(s)

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights[12] (ICCPR, 1966)

Article 6(2) of the ICCPR permits the use of the death penalty as a mode of punishment in countries where it is still legal. However, its application is strictly limited to the most severe crimes, as defined by the law at the time the offense was committed. Execution can only occur after a final verdict by a competent court, ensuring due process. Importantly, Article 6 emphasizes that the death penalty must not violate principles of other international agreements, such as the Convention on Genocide.

While Article 6 allows for capital punishment in limited circumstances, it also clarifies that nothing in the article should prevent or delay the abolition of the death penalty by any State Party. This reflects the international movement towards restricting or eliminating the death penalty over time.

UN Safeguards and Resolutions

In 1984, the United Nations Economic and Social Council adopted the Safeguards guaranteeing protection of the rights of those facing the death penalty. These safeguards established procedural protections for individuals sentenced to death, including fair trial standards and access to legal counsel, aiming to prevent arbitrary or discriminatory application of capital punishment.[13]

At Italy’s instigation, and with the European Union’s sponsorship, a resolution calling for a moratorium on the use of the death penalty was introduced in the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) in 2007. The resolution, supported by New Zealand as a key facilitator, urged states retaining the death penalty to restrict its application, respect the rights of those on death row, and move progressively toward abolition. It also called upon abolitionist states not to reintroduce capital punishment. While not legally binding, the resolution marked an important political and moral milestone.

Since the adoption of Resolution 62/149 on 18 December 2007 (approved by 104 votes to 54, with 29 abstentions), the UNGA has reaffirmed the moratorium every two years, with steadily increasing support:

- 2008 (A/RES/63/168): 106 in favour, 46 against, 34 abstentions.

- 2010 (A/RES/65/206): 109 in favour, 41 against, 35 abstentions.

- 2012 (A/RES/67/176): 111 in favour, 41 against, 34 abstentions.

- 2014 (A/RES/69/186): 117 in favour, 38 against, 34 abstentions.

- 2016 (A/RES/71/187): 117 in favour, 40 against, 31 abstentions.

- 2018: 121 in favour, 35 against, 32 abstentions.

- 2020: 123 in favour, 38 against, 24 abstentions.

- 2022: 125 in favour, 37 against, 22 abstentions.

- 2024: 130 in favour, 32 against, 22 abstentions.

This growing trend reflects the progressive consolidation of international consensus against the death penalty, reaffirming the UN’s commitment to advancing human dignity, due process, and the right to life.[14]

Second Optional Protocol to the ICCPR[15] (1989)

The Second Optional Protocol to the ICCPR marked a decisive step towards abolition. States that ratify the Protocol undertake a binding commitment not to execute anyone within their jurisdictions. While India has not ratified this Protocol, it represents a key international legal instrument that sets a global standard for the elimination of the death penalty.

'Death Penalty' as defined in official government report(s)

35th Law Commission Report[16] (1967)

The 35th Law Commission Report undertook a detailed examination of the legal framework governing the death penalty in India, including eligibility criteria, procedural safeguards, and systemic shortcomings in enforcement. The report emphasized that capital punishment should be reserved only for the most serious offences, aligning with emerging international human-rights standards. It highlighted significant disparities in the imposition of death sentences across different states and a lack of uniform data on executions. Additionally, the report drew attention to the “death row phenomenon”, wherein prisoners spend prolonged periods awaiting the disposal of appeals and mercy petitions, leading to considerable psychological suffering.

The report also stressed the need for procedural reforms to ensure fair administration of justice and compliance with Article 21 jurisprudence. These reforms include ensuring legal representation at all stages, setting clear timelines for appeals and clemency, improving record-keeping, and enhancing transparency in the disposal of mercy petitions.

Policy Proposals: The Commission recommended restricting the death penalty to crimes involving loss of life with exceptional aggravating circumstances. It called for publishing anonymised, state-wise data on death sentences and executions to improve transparency. The report also proposed streamlining the mercy petition process to prevent undue delays and reduce the psychological strain of prolonged uncertainty. It suggested establishing independent advisory boards to assist the executive in clemency decisions, thereby reducing arbitrariness. Finally, it recommended that mitigating factors such as socio-economic background, age, mental health, gender, and minority status should be duly considered to prevent discriminatory application.

187th Law Commission Report[17] (2003)

The 187th Law Commission Report addressed the issue of the death penalty focusing on the mode of execution and related procedural matters. The Commission undertook this study suo motu in light of advancements in science, technology, medicine, and anaesthetics. It did not engage with the broader debate on the abolition or retention of the death penalty, instead concentrating on whether the existing mode of execution met standards of humanity and decency.

The report highlighted the need for more humane methods of execution and recommended developing standardized procedures and oversight mechanisms to ensure uniformity and dignity in the execution process. The Commission’s focus was procedural rather than normative, aiming to align the method of execution with evolving technological and medical standards.

262nd Law Commission Report[18] (2015)

The 262nd Law Commission Report, under the chairmanship of Justice A.P. Shah, revisited the subject of the death penalty in India in the context of contemporary judicial developments, such as Santosh Kumar Satishbhushan Bariyar v. State of Maharashtra (2009) and Shankar Kisanrao Khade v. State of Maharashtra (2013). The report critically examined the penological purpose of capital punishment, evaluating whether it effectively serves as a deterrent and whether its application is consistent and constitutionally valid.

The Commission concluded that the death penalty does not act as a greater deterrent than life imprisonment and noted the inconsistent application of the “rarest of rare” doctrine established in Bachan Singh v. State of Punjab (1980), which leads to arbitrariness and violates principles of equality. The report highlighted systemic weaknesses, including outdated investigative methods, overburdened police forces, inefficient prosecution, and inadequate legal aid, which increase the risk of wrongful convictions. It criticized the use of the death penalty as symbolic victim justice, arguing that it neglects restorative and rehabilitative justice.

The Commission recommended abolishing the death penalty for all offences except terrorism-related crimes, while reforming sentencing practices to ensure consistency and fairness. It advocated for strengthening institutional capacity in investigation, prosecution, and legal aid, and for prioritizing restorative justice mechanisms over retributive punishment. Although it recognized national security concerns as a factor for retaining the death penalty in terrorism cases, the report emphasized that there is no compelling penological justification for capital punishment in general.

'Term' as defined in case law(s)

Constitutional Legitimacy of the Death Penalty

Jagmohan Singh v. State of Uttar Pradesh[19] (1973)

The Supreme Court upheld the constitutional validity of the death penalty, holding that the “deprivation of life” is lawful when carried out according to a “procedure established by law” under Article 21. The Court observed that capital punishment was not unreasonable or contrary to public interest, noting that the legislature had chosen not to abolish it despite prolonged debate. This decision established that the judicial process of sentencing under the CrPC was itself sufficient procedural safeguard against arbitrariness.

Interpretation of “Special Reasons” under Section 354(3) CrPC

Rajendra Prasad v. State of Uttar Pradesh[20] (1979)

The Court interpreted the requirement of “special reasons” for imposing a death sentence under Section 354(3) of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973. It held that such reasons must relate to the offender rather than the offence alone. The judgment emphasized that capital punishment should be imposed only when reformation is impossible, marking a shift towards a reformative and humanistic philosophy of punishment. The Court cautioned against awarding the death penalty based solely on the brutality of the act unless it revealed an irreparable depravity or chronic criminal tendency.

Doctrine of the “Rarest of Rare”

Bachan Singh v. State of Punjab[21] (1980)

In this landmark case a Constitution Bench upheld the constitutional validity of the death penalty under Section 302 IPC and Section 366(2) CrPC by a 4:1 majority. The Court laid down the “rarest of rare” doctrine, limiting the imposition of capital punishment to exceptional cases where life imprisonment is “unquestionably foreclosed.” It held that sentencing courts must balance aggravating and mitigating factors concerning both the crime and the criminal. The judgment constitutionalized sentencing discretion, requiring individualized consideration before awarding the death penalty.

Invalidation of Mandatory Death Sentences

Mithu v. State of Punjab[22] (1983)

The Supreme Court struck down Section 303 of the IPC—which mandated the death penalty for life convicts committing murder—as unconstitutional. The Court reasoned that such a mandatory provision violated Articles 14 and 21, as it excluded judicial discretion and failed to consider mitigating circumstances. This judgment reinforced that every convict, regardless of the nature of the offence, must have an opportunity for individualized sentencing based on personal and situational factors.

Scope of Presidential Power under Article 72

Kehar Singh v. Union of India[23] (1989)

The Court examined the scope of the President’s power to grant mercy under Article 72. It held that the President may scrutinize the evidence, re-examine the case on merits, and reach conclusions independent of the judiciary. However, this exercise of power is distinct from judicial review, as the President acts under a constitutional prerogative rather than judicial authority. This decision clarified that executive clemency serves as a final humanitarian safeguard within the constitutional framework.

Contemporary Validity and Reformative Approach

Channulal Verma v. State of Chhattisgarh[24] (2018)

The continuing constitutionality of the death penalty was questioned in light of the principles of reformative justice. Although the majority upheld the sentence, the Court acknowledged the need for reconsidering the moral and legal justifications for capital punishment in a modern rights-based framework. Ultimately, the death sentence was commuted to life imprisonment, considering the convict’s good conduct in prison and potential for reform. This case reflects the judiciary’s increasing discomfort with the irrevocable nature of capital punishment.

International variations:

Global Trends and Data (2024)

In 2024, the highest number of executions occurred in China, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, and Yemen, in that order. China remains the world’s leading executioner, but the exact extent of executions is unknown because the government classifies death penalty data as a state secret. Amnesty International recorded at least 1,518 executions in 15 countries globally, a 32% increase from 2023, excluding China’s unreported figures. Excluding China, 87% of reported executions took place in Iran and Saudi Arabia, indicating a regional concentration in the use of capital punishment.

Globally, at least 2,087 death sentences were recorded in 46 countries in 2024, and 28,085 individuals were under sentence of death by the end of the year. These figures highlight both the continuing retention of the death penalty in certain countries and the challenges of accurate global data collection, particularly in jurisdictions where executions are classified as state secrets.[25]

Abolition and Moratoriums

Since 1976, more than 85 countries have abolished the death penalty for all crimes, while others have abolished it for ordinary crimes. For example, Brazil, Argentina, Poland, and South Africa abolished capital punishment for ordinary crimes, whereas Portugal, Denmark, France, Australia, and New Zealand abolished it for all crimes. In 2022, Papua New Guinea, Central African Republic, Equatorial Guinea, and Zambia became the latest countries to abolish the death penalty for all offenses.

Deviation from Indian practice: India remains a retentionist state, maintaining capital punishment for the “rarest of rare” cases, unlike many jurisdictions that have eliminated or restricted the death penalty entirely.[26]

Country-Specific Practices and Operationalisation

China

China continues to carry out the highest number of executions, with the death penalty applicable to 46 offenses, including some non-lethal crimes, which diverges from the international standard of restricting it to the “most serious crimes.” In 2007, the Supreme People’s Court assumed responsibility for reviewing all death sentences, improving oversight. Reforms, including eliminating the death penalty for 13 nonviolent crimes in 2011 and prohibiting execution for individuals aged 75 and above, indicate gradual alignment with procedural safeguards. The Code of Criminal Procedure (2012) requires final appeals to be heard by the Supreme People’s Court, representing a best practice in centralized judicial review.

Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan has had a moratorium on executions since 2003. The country ratified the Second Optional Protocol to the ICCPR in 2020, entering into force in 2022, formally abolishing the death penalty for all crimes and replacing it with life imprisonment. Kazakhstan demonstrates progressive operationalisation by combining legislative reform, moratoriums, and international treaty obligations.

United States of America

The U.S. Supreme Court has shaped the operationalisation of the death penalty through constitutional interpretation. Furman v. Georgia (1972) struck down existing laws as unconstitutional, but Gregg v. Georgia (1976) reinstated the death penalty with safeguards, allowing it only when retribution and deterrence purposes were met. Coker v. Georgia (1977) further emphasized proportionality, while intellectual or developmental disability and juvenile status prohibit capital punishment. These cases exemplify a structured judicial framework ensuring compliance with constitutional safeguards, a model for embedding procedural justice and proportionality in death penalty administration.

Official Database

Project 39A: Death Penalty India Report (DPIR) Database[27]

Project 39A, affiliated with the National Law University, Delhi, maintains the Death Penalty India Report (DPIR) Database, which is a comprehensive repository of death penalty cases in India. The database captures legal, demographic, and procedural information for individuals sentenced to death, drawing primarily from Supreme Court and High Court judgments, appeals, and mercy petition outcomes.

The database includes various data fields such as personal details (name, age, gender, socio-economic background), legal information (case number, court, date of sentencing, appellate history), offense type (e.g., murder, terrorism), execution status (death sentence, commuted sentence, or pending), and procedural indicators (trial dates, appeals, mercy petitions).

The DPIR portal provides a searchable interface and downloadable records for researchers.

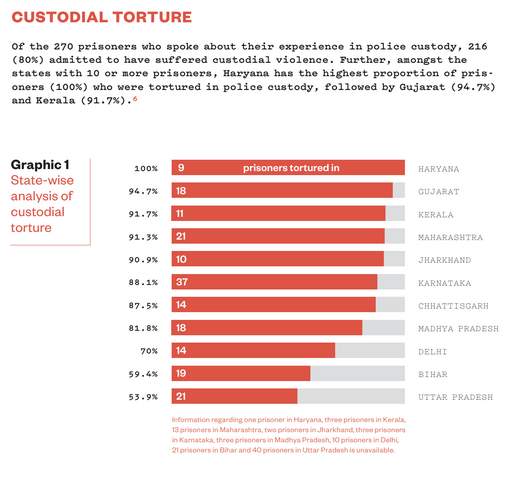

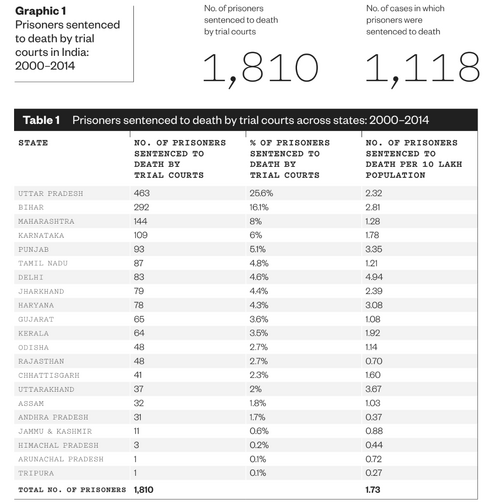

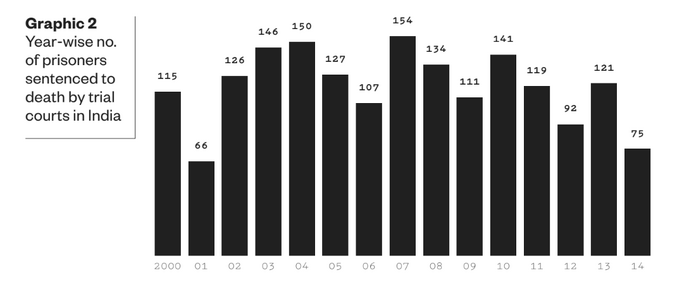

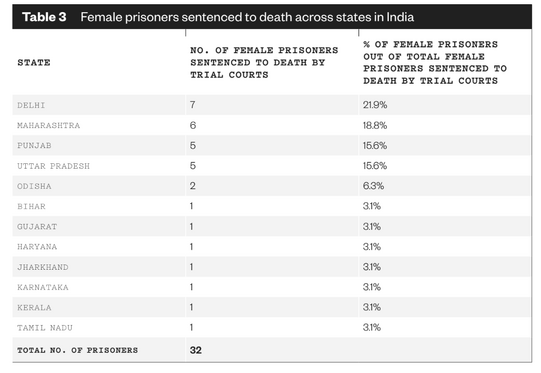

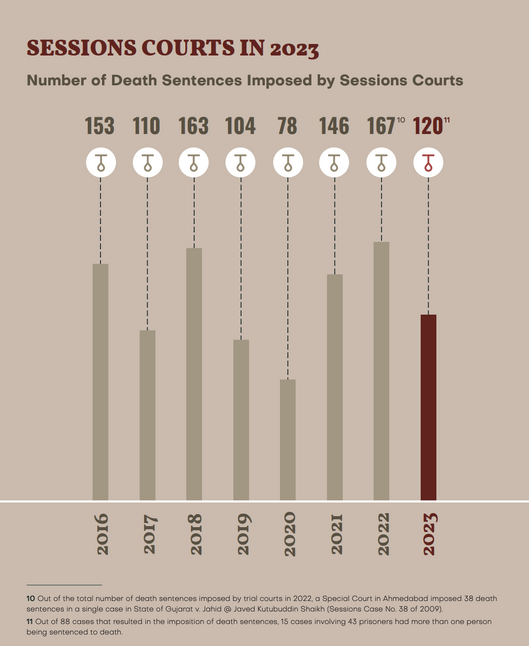

Statistics from Volume 2 of the Death Penalty India Report

Project 39A: Annual Statistics Report[28]

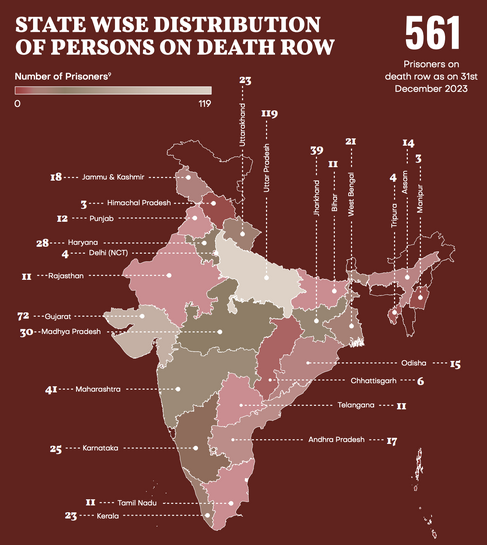

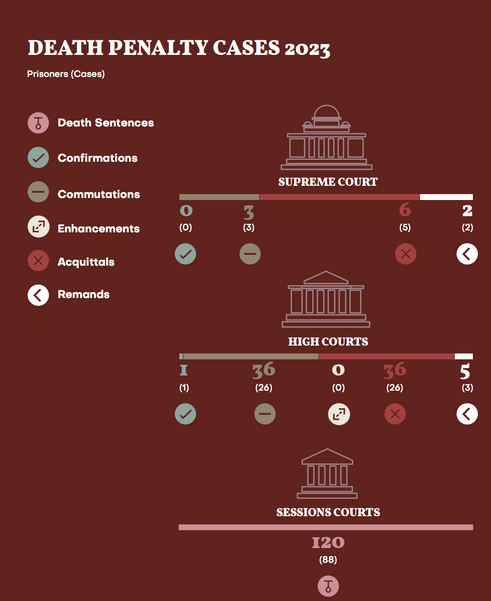

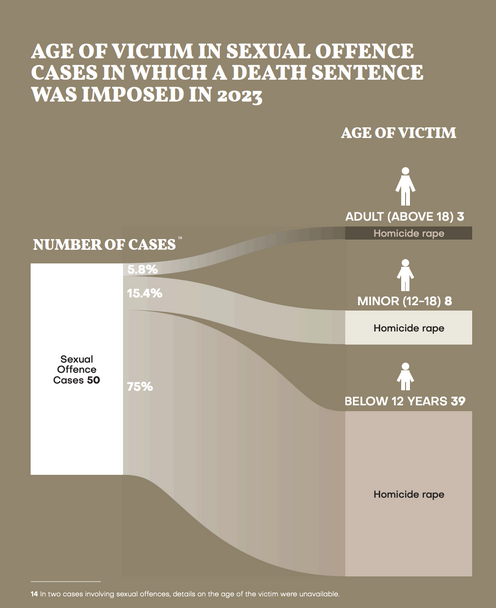

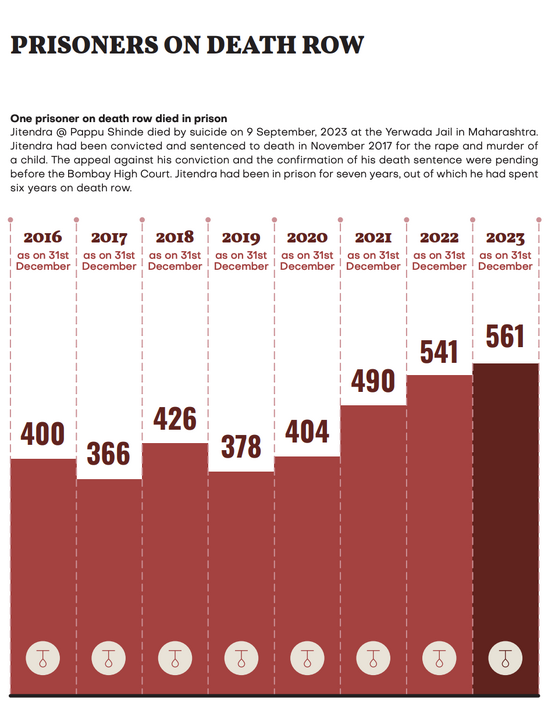

The Annual Statistics Report consolidates quantitative data on death penalty trends in India for the reporting year. It emphasizes aggregated statistics, including case counts, demographic distributions, and procedural outcomes across the country.

Data fields include aggregate counts of death sentences, commutations, and executions, as well as demographic variables such as age, gender, caste, and region. The report also tracks judicial process indicators, like the number of appeals filed and pending mercy petitions, and categorizes crimes into murder, terrorism-related offenses, and other offenses.

The Annual Statistics Report has been released annually since 2016, making it one of the most consistent and comprehensive datasets on the administration of the death penalty in India. Each edition is publicly accessible through their website and available for download in PDF format, presenting data through detailed tables, charts, and graphs for clarity and ease of analysis.

Statistics from the Annual Statistics Report 2023[29] - the most recent one

Research that engages with 'Death Penalty'

Lethal Lottery: Death Penalty in India by Amnesty International & People’s Union for Civil Liberties[30] (2008)

This report analyzes over 700 Supreme Court judgments spanning 1950–2006 and highlights the arbitrariness and inconsistencies in the Indian death penalty system. It argues that the “rarest of rare” principle is frequently ignored, legal representation is often inadequate, and sentencing is prone to administrative and judicial errors. The research emphasizes that capital punishment has been applied in an imprecise and abusive manner, undermining constitutional values such as fairness, equality, and due process.

Prisoner Voices from Death Row: India Experience by Reena Mary George[31] (2015)

This study documents the demographic profile of death row prisoners and traces the procedural journey from arrest to sentencing. It highlights the impact of capital punishment on prisoners’ families and shows how socio-economic marginalization, poverty, and social exclusion correlate with death sentences. The research provides qualitative insight into the human cost of the death penalty and the psychological and social ramifications for convicts and their families.

Death Penalty India Report (DPIR), Project 39A, NLU Delhi[32] (2016)

This report presents extensive quantitative and qualitative data on death row prisoners in India. Out of 385 prisoners and their families interviewed, the report found that 74% were economically vulnerable, 76% belonged to backward communities, and a significant proportion lacked secondary education. Of over 1,700 death sentences from 2000–2015, appellate courts confirmed only 4.5%, with ~30% acquitted and ~65% commuted to life imprisonment. The report also documents experiences with police investigation, trial, appeal, incarceration, and family relationships, revealing systemic flaws in legal representation, trial procedures, and administrative safeguards.

Matters of Judgment, Project 39A, NLU Delhi[33] (2017)

An opinion study of 60 former Supreme Court judges who collectively adjudicated 208 death penalty cases (1975–2016). It investigates judicial attitudes toward sentencing, trial processes, and the application of the “rarest of rare” doctrine. The study finds significant variability in judicial interpretation, reflecting systemic inconsistency and the lack of uniform standards in death penalty sentencing.

Death Penalty Sentencing in Trial Courts, Project 39A, NLU Delhi[34]

This research analyzed 215 trial court judgments from Delhi, Madhya Pradesh, and Maharashtra (2000–2015) to uncover procedural and normative gaps in death penalty sentencing. It demonstrates the challenges in applying the Bachan Singh framework consistently and the legacy of systemic inconsistencies originating from trial court levels.

Death Penalty Annual Statistics Report, Project 39A, NLU Delhi[28] (2016–present)

These annual reports provide updated data on death row populations, new death sentences, and execution trends in India. For instance, trial courts imposed 162 death sentences in 2018, the highest since 2000, decreasing to 102 in 2019. The reports track both legal and socio-political developments affecting capital punishment and facilitate longitudinal study of systemic patterns.

Challenges

The death penalty faces significant challenges across moral, legal, and practical dimensions. It is criticized for its brutality, as execution (regardless of the method) inflicts irreversible physical harm and reflects a continuation of inhumane punishment practices. Questions of dignity arise because the deliberate taking of life by the state is seen as degrading to human worth and inconsistent with the principle of respecting individual rights.The effectiveness of the death penalty as a deterrent remains unproven. Studies show no clear link between executions and lower homicide rates, suggesting that certainty of punishment, not severity, is what deters crime. Moreover, human rights concerns have intensified globally, as capital punishment is viewed as incompatible with modern democratic values and the right to life. Many nations have abolished it in recognition of its potential for arbitrariness, wrongful conviction, and violation of human dignity.[35]

Way Ahead

Related Terms

Capital Punishment · Execution · Mercy Petition · Clemency · Death Row.

References

- ↑ https://www.mha.gov.in/sites/default/files/250883_english_01042024.pdf

- ↑ https://www.indiacode.nic.in/repealedfileopen?rfilename=A1860-45.pdf

- ↑ https://mod.gov.in/dod/sites/default/files/TheArmyAct1950.pdf

- ↑ https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/1814/1/aA1988-03.pdf

- ↑ https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/18974/1/narcotic-drugs-and-psychotropic-substances-act-1985.pdf

- ↑ https://www.indiacode.nic.in/SpentActFileOpenServlet?sfilename=A1962-51.pdf

- ↑ https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/16362/3/maharashtra_control_of_.pdf

- ↑ https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/8190/1/1_of_2002_%28e%29.pdf

- ↑ https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/1559/3/a1960-6.pdf

- ↑ https://prsindia.org/files/bills_acts/bills_parliament/2023/Bharatiya_Nagarik_Suraksha_Sanhita,_2023.pdf

- ↑ https://cara.wcd.gov.in/pdf/jj%20act%202015.pdf

- ↑ https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/international-covenant-civil-and-political-rights

- ↑ https://www.unodc.org/pdf/criminal_justice/Safeguards_Guaranteeing_Protection_of_the_Rights_of_those_Facing_the_Death_Penalty.pdf

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Resolutions_concerning_death_penalty_at_the_United_Nations

- ↑ https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/international-covenant-civil-and-political-rights

- ↑ https://cdnbbsr.s3waas.gov.in/s3ca0daec69b5adc880fb464895726dbdf/uploads/2022/08/2022080828-1.pdf

- ↑ https://cdnbbsr.s3waas.gov.in/s3ca0daec69b5adc880fb464895726dbdf/uploads/2022/08/2022081073.pdf

- ↑ https://cdnbbsr.s3waas.gov.in/s3ca0daec69b5adc880fb464895726dbdf/uploads/2022/08/2022081670.pdf

- ↑ https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1837051/

- ↑ https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1309719/

- ↑ https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1235094/

- ↑ https://admin.caseguru.in/storage/uploads/judgement_pdf/Mithu%20vs%20State%20oF%20Punjab.pdf

- ↑ https://digiscr.sci.gov.in/view_judgment?id=MjM5NTM=

- ↑ https://indiankanoon.org/doc/122892663/

- ↑ https://www.amnesty.org/en/what-we-do/death-penalty/

- ↑ https://www.amnesty.org/en/what-we-do/death-penalty/

- ↑ https://www.project39a.com/dpir

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 https://www.project39a.com/annual-statistics-reports

- ↑ https://www.project39a.com/annual-statistics-report-2023

- ↑ https://www.amnesty.org/en/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/asa200072008eng.pdf

- ↑ https://books.google.co.in/books/about/Prisoner_Voices_from_Death_Row_Indian_Ex.html?id=6CPmsgEACAAJ&redir_esc=y

- ↑ https://www.project39a.com/dpir

- ↑ https://www.project39a.com/moj

- ↑ https://www.project39a.com/dpsitc

- ↑ https://www.indianbarassociation.org/death-penalty-contemporary-issues/