Dishonour of Cheque

What is Dishonour of Cheque

Dishonour of a cheque refers to the situation where a bank refuses to honour a cheque presented for payment. This typically occurs due to insufficient funds in the drawer's account, discrepancies in the cheque such as a mismatch in signature, or the closure of the drawer’s account. The dishonouring of a cheque is not only a financial inconvenience but also a legal issue that can result in criminal liability under the Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881.

Official Definition of Dishonour of Cheque

Dishonour of Cheque as defined in legislations

Negotiable Instruments Acts, 1881

The dishonour of a cheque is primarily addressed under Section 138 of the Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881[1], which makes it an offence if a cheque is dishonoured due to insufficient funds, among other reasons. This provision has been a significant tool in regulating financial transactions and combating cheque-related fraud.

Legal provisions relating to Dishonour of Cheques

What is a Negotiable Instrument?

Section 13 of the Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881[2] defines a "negotiable instrument" as a promissory note, bill of exchange, or cheque that is payable either to order or to bearer. Explanation (i) clarifies that such instruments are payable to order when explicitly stated or payable to a specific person without words prohibiting transfer or indicating non-transferability. Explanation (ii) states that an instrument is payable to bearer when explicitly expressed or when the only or last endorsement is in blank. Explanation (iii) provides that an instrument payable to the order of a specified person is still payable to that person or their order at their option. Furthermore, negotiable instruments can be made payable to two or more payees jointly or alternatively to one or more payees.

What is a Cheque?

A cheque, as defined under Section 6 of the Negotiable Instruments Act,[3] is a type of bill of exchange drawn on a specific banker, with the condition that it is payable only on demand. The definition also encompasses modern forms of cheques, including the electronic image of a truncated cheque and a cheque in electronic form.

Ingredients:

Section 138 of the Negotiable Instruments Act penalises the dishonour of a cheque; however, the dishonour itself does not constitute an offence unless specific conditions are met. The essential ingredients of the offence under Section 138 are as follows: (a) The cheque must be issued by the drawer to the payee/complainant from a bank account maintained by the drawer. (b) It must be issued for the discharge of a legally enforceable debt or liability, either wholly or partially. (c) The cheque is dishonoured by the bank due to insufficient funds or because it exceeds the agreed payment limit with the bank. (d) The cheque must be presented within three months from the date it was drawn or within its validity period. (e) The payee or holder must issue a demand notice within 30 days of receiving information about the dishonour from the bank. (f) The drawer must fail to make the payment within 15 days of receiving the notice. (g) The debt or liability for which the cheque was issued must be legally enforceable. (h) If the drawer fails to make the payment within the 15-day period, the offence is established. These requirements are highlighted in the case of Kusum Ingots and Alloys Ltd. v. Pennar Peterson Securities Ltd.[4]

Time Frame

The time frame for the offence under Section 138 is as under:

Presentation of the Cheque: The cheque must be presented to the bank within three months from the date it is drawn or within its validity period, whichever is earlier, as per the Reserve Bank of India's notification reducing the validity period from six months to three months. [Section 138 proviso (a)]

Demand Notice: The payee or holder in due course must issue a written demand notice to the drawer within 30 days of receiving information from the bank about the dishonour of the cheque. [Section 138 proviso (b)]

Payment by Drawer: The drawer must fail to make the payment within 15 days of receiving the notice. [Section 138 proviso (c)].

Filing of Complaint: The complaint must be filed within one month from the date on which the cause of action arises under clause (c) of the proviso to Section 138. [Section 142][5]

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) issued a notification on November 4, 2011, highlighting concerns over the misuse of cheques, drafts, pay orders, and banker’s cheques being circulated like cash during their six-month validity period. To address this issue, the RBI announced a reduction in the validity period of such instruments from six months to three months.

This directive, issued under Section 35A of the Banking Regulation Act, 1949, mandated that banks should not honor cheques, drafts, pay orders, or banker’s cheques if presented beyond three months from the date of issuance. The new rule came into effect from April 1, 2012, to ensure greater control and prevent the misuse of negotiable instruments.

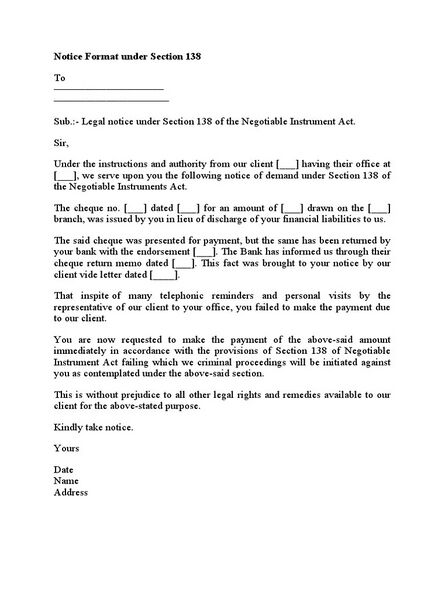

What is a Demand Notice?

The demand notice must be issued in writing within 30 days of receiving information from the bank regarding the dishonor of the cheque. While calculating this period, the date of receipt of information is excluded. The Supreme Court in K. Bhaskaran v. Sankaran and Dalmia Cement (Bharat) Ltd. v. M/s Galaxy Traders[6] clarified that the offense under Section 138 arises only after the accused receives the notice, as the cause of action depends on its receipt. Additionally, in cases where the notice is returned with postal remarks like "refused" or "not available," courts have held that such notices are deemed served (State of M.P. v. Hira Lal and Jagdish Singh v. Nathu Singh). In C.C. Alavi Haji v. Palapetty Muhammad[7], the Court noted that under Section 27 of the General Clauses Act[8], service is presumed when a notice is sent by registered post to the correct address, unless proven otherwise. Moreover, a drawer who fails to pay within 15 days of receiving summons cannot later claim improper service of the notice.

Issuance of a second demand notice - Courts have discouraged issuing a second demand notice for the same dishonored cheque. In Sumitra Sankar Dutta v. Biswajit Paul[9], the Gauhati High Court held that if the first notice is deemed served, a second notice cannot be issued. Similarly, the Supreme Court in Tameeshwar Vaishnav v. Ramvishal Gupta stated that a payee who fails to act within the prescribed period after the first notice cannot send a fresh notice for the same cheque.

Content of the demand notice - In Suman Sethi v. Ajay K. Churiwal[10], the Supreme Court emphasized that the notice must demand the "said amount" (i.e., the cheque amount). If additional claims like interest or damages are included, they must be specified separately. Any vague or omnibus demand that fails to specify the amount due under the dishonored cheque may render the notice legally invalid. However, in M.M.T.C. Ltd. v. Medchal Chemicals and Pharma (P) Ltd.[11], the Court clarified that the complainant is not required to explicitly allege the existence of a legally enforceable debt in the notice. The burden of proving the absence of such a debt lies on the accused.

Cognizance

Section 142 of the Negotiable Instruments (NI) Act governs cognizance of offences under Section 138. Complaints must be filed in writing by the payee or holder of the cheque within one month of the cause of action arising. Courts may condone delays if sufficient cause is shown. Only a Metropolitan Magistrate or Judicial Magistrate First Class can try offences under Section 138. Jurisdiction is determined based on:

The bank branch where the payee maintains the account (if the cheque is delivered for collection). The drawer’s bank branch (if the cheque is presented directly for payment).

Time Limits

The NI Act prescribes strict time limits for prosecuting offences under Section 138: 1. Cheques must be presented within their validity (3 months). 2. Notice demanding payment must be sent within 15 days of dishonour. 3. Complaints must be filed within one month of the cause of action (16th day after the notice period).

Liability of Guarantor Under Section 138 of the Negotiable Instruments Act

The question of whether a guarantor can be held liable for prosecution under Section 138 of the Negotiable Instruments Act (N.I. Act) if a cheque issued on behalf of the principal debtor gets dishonoured is significant. The answer is affirmative, as the liability of the guarantor and the principal debtor is coextensive.

In Don Ayengia v. State of Assam & Another[13], The Gauhati High Court deliberated on whether a guarantor could be held liable under Section 138 of the N.I. Act for indemnifying the principal debtor’s liability. The Court concluded in the negative, stating that a guarantor could not be prosecuted unless they entered into an agreement with the cheque holder.

In I.C.D.S. Ltd. v. Beena Shabbir & Anr.[14], The Supreme Court provided definitive clarity on the legislative intent of Section 138, emphasising the expressions "any cheque" and "other liability." The judgment noted that the statute does not impose restrictions based on whether the debt or liability arises from a guarantee or any other context, reaffirming that Section 138 applies wherever a cheque is dishonoured in the discharge of a liability. The Court stated: "Any interpretation restricting the guarantor’s liability would defeat the legislative intent and purpose of the statute."

Interim Compensation and its Recovery under Section 143A of the Negotiable Instruments Act

Section 143A of the Negotiable Instruments Act (N.I. Act) grants the court the discretion to award interim compensation during the pendency of proceedings in cheque bounce cases. While this power is discretionary, the Supreme Court has issued guidelines to clarify how this discretion should be exercised, as seen in the case of Rakesh Ranjan Shrivastava v. The State of Jharkhand & Anr.[15] The Supreme Court held that the provision under Section 143A is discretionary, as indicated by the use of the word “may” in the statute. This contrasts with the mandatory nature of similar provisions, such as those under Section 148 of the N.I. Act, which involves post-conviction compensation. In the case of Rakesh Ranjan Shrivastava, the complainant filed a case under Section 138 of the N.I. Act, alleging dishonour of a cheque issued for business ventures. The complainant sought interim compensation under Section 143A, which was granted by the trial court and upheld by the Jharkhand High Court. The appellant challenged this decision before the Supreme Court, arguing that the provision's discretionary nature meant that the court should not have ordered compensation.

Dishonour of Cheque as defined in official government report

213th Law Commission Report on Fast Track Magisterial courts for Dishonoured Cheque Cases

The '213th Report On Fast Track Magisterial Courts For Dishonoured Cheque Cases'[16] addresses the challenges faced by India's judicial system, specifically focusing on the delay in the disposal of cases and the need for reforms to ensure speedy justice. The report emphasises the constitutional promise of providing all citizens with equal access to justice, particularly for the poor and needy. However, delays in the court system hinder this goal, with the judiciary, executive, and legislature needing to cooperate more effectively to address the issue. The establishment of Fast Track Courts, especially for criminal cases like dishonoured cheques, is proposed as a solution. These courts would have modern infrastructure and ad hoc judges, with a performance-based approach to future promotions. However, challenges such as adjournments, lack of coordination between law enforcement agencies, and insufficient resources for courts have led to prolonged trials. This delays the justice process, causing hardship to both the accused and the victims.

The report stresses that while speedy trials are essential, they must be fair, and the judiciary must adapt to changing circumstances. The report also advocates for better infrastructure, such as court buildings and facilities for witnesses, to improve the justice delivery system. Furthermore, it highlights the importance of a fair and speedy trial as a constitutional right, with the Supreme Court emphasising the need for the state to ensure timely trials for undertrial prisoners. Finally, the report calls for ongoing modernisation and the setting up of more courts to handle the growing caseload and reduce case backlogs.

Dishonour of Cheque as defined in case laws

Msr Leathers vs. S. Palaniappan and Anr., 2016

In this case, the court extensively analysed the conditions necessary for an offence to be committed under Section 138 of the Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881 (hereinafter "the Act"). The offence of dishonour of a cheque is conditional on three key requirements being met: 1. The cheque must be presented within six months of being drawn, or within its validity period, whichever comes first. 2. The payee or holder in due course must give written notice within thirty days of receiving information from the bank that the cheque has been dishonoured. 3. The drawer must fail to pay the cheque amount within fifteen days of receiving the notice. If these conditions are fulfilled, an offence under Section 138 is committed.[17]

M/S East-West Fire v. M/S Vasu Infosec, 2015

In this case, the court ruled that the term "security cheque" is not defined in the Negotiable Instruments Act (N.I. Act). The court emphasised that a defence claiming the dishonoured cheque was a security cheque would not absolve the drawer from liability under Section 138. This was supported by the judgment in Suresh Chandra Goyal v. Amit Singhal (2015), which defined a security cheque as one used to honour debts that may arise in the future. Regarding interim compensation, Section 143A, introduced through the 2018 amendment, allows courts to grant compensation during the pendency of proceedings under Section 138. If the drawer has not pleaded guilty, they must pay interim compensation, which cannot exceed 20% of the cheque amount.[18]

S.R. Muralidhar v. G.Y. Ashok, 2010

When a blank cheque is issued, where the drawer signs the cheque but leaves the other details, such as the payee's name, date, and amount, to be filled in later, it remains valid in law. Section 20 of the Negotiable Instruments Act addresses this by allowing a signed cheque to be filled in as agreed by the parties. If such a cheque is dishonoured, Section 138 applies, and the drawer can be held liable for the dishonour.[19]

Modi Cements Ltd. v. Kuchil Kumar Nandi,1998

What is the Effect of Issuing 'Stop Payment' Instructions? No, the liability of the drawer is not absolved by issuing ‘stop payment’ instructions to the bank or notifying the payee not to present the cheque. If the cheque was issued in discharge of an existing debt or liability, issuing stop payment instructions does not remove the liability of the drawer. As clarified in this case, the drawer's obligation remains, and penal liability persists even with the stop payment instructions.[20]

Dhanasingh Prabhu vs Chandrasekar, 2025

The Supreme Court addressed the issue, whether a complaint under Section 138 of the Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881 is maintainable against the partners of a partnership firm, even if the firm itself is not named as an accused or served with a statutory notice under Section 138.[21] held that in cheque bounce cases under Section 138 read with Section 141 NI Act, partners of a firm are “personally, jointly and severally liable” along with the firm, even if the firm itself is not named in the complaint or served notice. The Court clarified that a partnership firm lacks juristic personality separate from its partners, so serving notice on or prosecuting the partners equates to serving the firm. It was observed that “Notice to partners is notice to the firm”, and the omission of the firm as an accused is not fatal or uncurable for the complaint’s maintainability.

Stages in a Cheque Bounce Case.

The process for handling a dishonoured cheque involves several stages. First, the complainant must file a complaint within 30 days of the cheque being dishonoured, after which the magistrate reviews the case and, if deemed appropriate, issues summons to the accused. The complainant then provides a sworn statement, and based on this, the magistrate decides whether to proceed further. If satisfied, summons are issued. The accused must appear in court, and failure to do so may result in an arrest warrant; bail is required, either with surety or cash security. During the recording of the plea, the accused is asked to plead guilty or not guilty. If guilty, sentencing occurs immediately; otherwise, the case proceeds to evidence presentation. The complainant presents evidence and undergoes cross-examination, with additional witnesses testifying if needed. The accused is then given an opportunity to provide their statement and present defence evidence, which is also subject to cross-examination. Both parties then submit final arguments, often supported by case law. Finally, the court delivers its judgment. If the accused is found guilty, punishment is imposed, and they may appeal within 30 days. If acquitted, the case concludes.

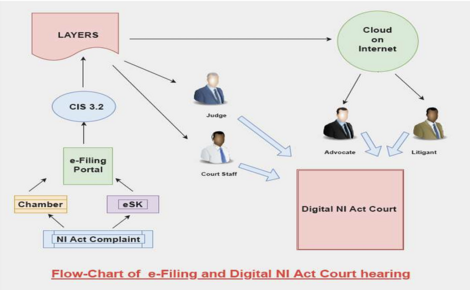

Digital Transformation:

In the case Makwana Mangaldas Tulsidas v. State of Gujarat and Another[22], a Bench of the Hon’ble Supreme Court, led by Chief Justice of India (CJI) Hon’ble Justice SA Bobde and Hon’ble Justice L Nageshwara Rao, issued important directions on 05.03.2020 concerning the establishment and enhancement of Exclusive Negotiable Instruments Act (N.I. Act) Courts. These directions aim to address the growing pendency of cheque dishonour cases and expedite the adjudication process. The key directions issued are summarized as follows:

1. High Courts are to consider the establishment of dedicated courts solely for the N.I. Act cases (Cheque Bounce Cases). This move aims to streamline the process of adjudication and reduce the delays caused by the mixing of N.I. Act cases with other criminal or civil cases.

2. The High Courts are to ascertain and set standard figures for the pendency of N.I. Act cases in district courts across the state. These standards will help in benchmarking the expected case load and will act as a guideline to assess whether additional courts are needed.

3. Where the pendency of N.I. Act cases exceeds the standard figures, the High Courts are instructed to set up Exclusive N.I. Act Courts. This step will target jurisdictions with high numbers of pending cheque bounce cases and ensure that these cases are handled more efficiently.

4. Special norms for work assessment are to be formulated for Exclusive N.I. Act Courts. These norms will focus on evaluating the performance and effectiveness of these specialized courts in handling cases under the N.I. Act, particularly in terms of speed and accuracy of adjudication.

International Experience

Countries around the world approach the issue of dishonoured cheques in varying ways, with each nation developing distinct definitions, operational processes, and methods of collecting data regarding dishonoured cheques. In the United States, the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC)[23] defines a dishonoured cheque as one that is returned due to insufficient funds in the drawer's account. Operationally, the UCC mandates that banks notify the payee of a dishonoured cheque, and the payee can pursue legal action if the issue is not resolved. Criminal charges may be brought against the drawer if fraud is suspected. In terms of data collection, organisations like the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB)[24] monitor and report on incidents of dishonoured cheques, especially in cases related to fraud.

How other countries have sought to define and operationalise regarding Dishonour of Cheque

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, cheques are legal instruments subject to regulations under the Bills of Exchange Act 1882[25] and the Cheques Acts of 1957 and 1992. Despite the digital evolution of payment systems, approximately 0.5% of cheques are still returned or bounced daily. A bounced cheque typically occurs when the drawer's bank account does not have sufficient funds to cover the cheque amount. According to Section 48 of the Bills of Exchange Act 1882, upon receiving notice of dishonour from the drawee bank, where the cheque is marked as "refer to drawer," the cheque bearer must promptly notify the drawer of the dishonour. The drawee bank may also charge a fee for the bounced cheque, which is subject to the bank’s policy. After seven days, the claimant has the option to initiate legal proceedings for the recovery of the cheque amount. This may include applying for summary judgment or issuing a bankruptcy petition against the drawer, if insolvency is suspected. However, the legal procedure can be costly and time-consuming, particularly when claims exceed £10,000, although this threshold allows for the recovery of fixed legal costs. Defences against a claim for dishonoured cheques are limited, typically revolving around issues like fraud, duress, misrepresentation, or complete incapacity. Crucially, there is no defence against cancelling a cheque once it has been issued because the drawer has essentially promised payment upon presenting the cheque.

United States of America

In the United States, the legal consequences of bouncing a cheque vary across states, but several general principles apply. Many states have introduced Bad Cheque Restitution Programs (BCRPs)[26], allowing recipients of bad cheques to recover the funds through local district attorney offices, irrespective of the cheque's value. If the cheque is paid within a certain period, usually sixty days, the associated criminal charges may be dismissed. However, for criminal prosecution to proceed, the cheque must typically involve fraudulent intent, such as issuing a cheque knowing there are insufficient funds to cover it. In some states, a warning from the cheque writer that the cheque will not be cleared immediately can prevent criminal prosecution, as it negates the element of fraud. Post-dated cheques, too, are usually not subject to bad cheque laws, since they promise payment at a future date rather than immediately. The penalties for issuing a bad cheque can be severe. For example, in New York, a person may face up to three months in jail and a fine of up to $750, while in Texas, bad cheque issuance is treated as a felony, punishable by imprisonment and fines.

Qatar

Cheque bouncing is treated as a criminal offense under Qatar’s Penal Code. Those who issue cheques without sufficient funds or with the intent of dishonoring the payment can face:

- Imprisonment for up to 3 years and/or a fine.

- The court may also order the withdrawal of the issuer's cheque book, preventing them from acquiring a new one for up to 1 year.

Additionally, a bounced cheque can severely damage the issuer’s credit, impacting their ability to obtain loans or credit in the future.

A travel ban can be imposed in Qatar due to a cheque bounce. This would prevent the individual from leaving the country until the outstanding debt is settled. The travel ban is an additional consequence, alongside the criminal penalties, which could affect employment and mobility. Note that complaints must be filed within three years from the date the cheque was dishonored.

Learnings

In the UK, a bounced cheque may lead to a civil claim for payment, and criminal cases are only pursued when fraud or intent to deceive is proven. However, the consequences are generally swift, with an emphasis on quick resolution through civil processes. India can learn from the UK’s efficient handling of cheque bounce cases through civil recovery processes, aiming for quicker resolution of cases, especially for non-fraudulent dishonor, to reduce court congestion.

Research that engages with Dishonour of Cheque

Get them to the court on time: bumps in the road to justice (The LEAP blog)

References

- ↑ Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881, Section 138.

- ↑ Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881, Section 13. https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?actid=AC_CEN_2_33_00042_00042_1523271998701§ionId=45588§ionno=13&orderno=13

- ↑ Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881, Section 6.https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?actid=AC_CEN_2_33_00042_00042_1523271998701§ionId=45581§ionno=6&orderno=6

- ↑ Kusum Ingots & Alloys Ltd. v. Pennar Peterson Securities Ltd., (2000) 2 SCC 745.https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1327885/

- ↑ Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881, Section 142.https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?actid=AC_CEN_2_33_00042_00042_1523271998701&orderno=147

- ↑ K. Bhaskaran v. Sankaran, (1999) 7 SCC 510.https://indiankanoon.org/doc/529907/

- ↑ C.C. Alavi Haji v. Palapetty Muhammad, (2007) 6 SCC 555 (Supreme Court of India). https://indiankanoon.org/doc/272690/

- ↑ General Clauses Act, 1897, Section 27

- ↑ Sumitra Sankar Dutta v. Biswajit Paul, (2004) 13 SCC 659 (Supreme Court of India).https://main.sci.gov.in/jonew/cl/advance/2024-02-20/M_J.pdf

- ↑ Suman Sethi v. Ajay K. Churiwal, (2003) 7 SCC 453 (Supreme Court of India).

- ↑ M.M.T.C. Ltd. v. Medchal Chemicals and Pharma (P) Ltd, 2006 (4) SCC 185.https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1438532/

- ↑ Scribd. https://www.scribd.com/document/638397229/LEGAL-DEMAND-NOTICE-format

- ↑ Don Ayengia v. State of Assam & Another, Cri. Apl. No. 10 of 2012 (Gauhati High Court).https://indiankanoon.org/doc/101920649/

- ↑ I.C.D.S. Ltd. v. Beena Shabbir & Anr., AIR 2002 SC 3014.https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1623811/

- ↑ Rakesh Ranjan Shrivastava v. The State of Jharkhand & Anr., (2020) 1 SCC 68. https://indiankanoon.org/doc/110578401/

- ↑ 213th Report of the Law Commission of India on Fast Track Magisterial Courts for Dishonoured Cheque Cases. https://indiankanoon.org/doc/72803968/

- ↑ Msr Leathers v. S. Palaniappan and Anr., (2006) 4 SCC 773. https://indiankanoon.org/doc/132373854/

- ↑ M/S East-West Fire v. M/S Vasu Infosec, (2015) 12 SCC 479. https://indiankanoon.org/doc/107100680/

- ↑ S.R. Muralidhar v. G.Y. Ashok, (2010) 4 SCC 276. https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1409258/

- ↑ Modi Cements Ltd. v. Kuchil Kumar Nandi, (1998) 1 SCC 91. https://indiankanoon.org/doc/975556/

- ↑ Dhanasingh Prabhu vs. Chandrasekar and Ors. (14.07.2025 - SC) : MANU/SC/0889/2025. https://indiankanoon.org/doc/113169443/#:~:text=It%20was%20therefore%20held%20that,mandated%20by%20Section%20141%20of

- ↑ Makwana Mangaldas Tulsidas v. State of Gujarat, (1976) 1 SCC 133.https://indiankanoon.org/doc/41019885/

- ↑ Uniform Commercial Code (UCC), U.S. Code. https://www.uniformlaws.org/acts/ucc#:~:text=The%20Uniform%20Commercial%20Code%20(UCC,the%20interstate%20transaction%20of%20business.

- ↑ Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, 12 U.S.C. § 5491 (2010). https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/12/5491

- ↑ Bills of Exchange Act, 1882, 45 & 46 Vict. c. 61 (UK).https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/Vict/45-46/61

- ↑ https://fotislaw.com/public/lawtify/laws-governing-bounced-cheques-in-uk-and-us