Domestic violence

What is Domestic Violence?

Domestic violence, often referred to as domestic abuse or family violence, involves abusive behavior by one person against another in a domestic setting, typically between individuals who share a familial or intimate relationship. It can take various forms, including physical, emotional, sexual, psychological, and economic abuse. Domestic violence can occur in marriages, cohabitations, or even between family members or intimate partners.[1] Despite its commonality, domestic violence remains an underreported and pervasive issue globally, often hidden behind closed doors. Victims are frequently trapped by fear, emotional bonds, or financial dependency, which can make it difficult to seek help or escape.[2]

Official definition of domestic violence

Domestic Violence as defined in Legislation(s)

Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005 (PWDVA)

In India, the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005 (PWDVA) plays a crucial role in safeguarding women against domestic violence.

Section 3 of the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005 (PWDVA) defines Domestic Violence as-

“Any act, omission or commission or conduct of the respondent shall constitute domestic violence in case it—

(a) harms or injures or endangers the health, safety, life, limb or well-being, whether mental or physical, of the aggrieved person or tends to do so and includes causing physical abuse, sexual abuse, verbal and emotional abuse and economic abuse; or

(b) harasses, harms, injures or endangers the aggrieved person with a view to coerce her or any other person related to her to meet any unlawful demand for any dowry or other property or valuable security; or

(c) has the effect of threatening the aggrieved person or any person related to her by any conduct mentioned in clause (a) or clause (b); or

(d) otherwise injures or causes harm, whether physical or mental, to the aggrieved person.”

As per Explanation - I of section 3 of D.V. Act, 2005

“Physical Abuse" means any act or conduct which is of such a nature as to cause bodily pain, harm, or danger to life, limb, or health or impair the health or development of the aggrieved person and includes assault, criminal intimidation and criminal force

“Sexual Abuse" includes any conduct of a sexual nature that abuses, humiliates, degrades or otherwise violates the dignity of woman;Harassment or injury caused due to unlawful demand of any dowry or other property or valuable security.

“Verbal and Emotional Abuse" includes

(a) insults, ridicule, humiliation, name calling and insults or ridicule specially with regard to not having a child or a male child; and repeated threats to cause physical pain to any person in whom the aggrieved person is interested;

“Economic Abuse" includes—

(a) deprivation of all or any economic or financial resources to which the aggrieved person is entitled under any law or custom whether payable under an order of a court or otherwise or which the aggrieved person requires out of necessity including, but not limited to, house hold necessities for the aggrieved person and her children, if any, stridhan, property, jointly or separately owned by the aggrieved person, payment of rental related to the shared house hold and maintenance;(b) disposal of household effects, any alienation of assets whether movable or immovable, valuables, shares, securities, bonds and the like or other property in which the aggrieved person has an interest or is entitled to use by virtue of the domestic relationship or which may be reasonably required by the aggrieved person or her children or her stridhan or any other property jointly or separately held by the aggrieved person; and (c) prohibition or restriction to continued access to resources or facilities which the aggrieved person is entitled to use or enjoy by virtue of the domestic relationship including access to the shared household

Bharatiya Nyay Sanhita, 2023

The newly enacted Bharatiya Nyay Sanhita, 2023 (formerly the Indian Penal Code) addresses domestic violence and cruelty within marital relationships. Section 85 deals specifically with cruelty by a husband or his relatives towards a woman, with punishments that include imprisonment of up to three years and fines[3]. This section is a direct continuation of the protection offered under the now-repealed Section 498A of the Indian Penal Code.[4] Section 86 further defines cruelty as conduct that could drive a woman to suicide, or inflict grave harm or danger to her physical or mental health, or coercive actions related to dowry demands.

Legal Provisions relating to Domestic Violence

Reliefs and Remedies under the Domestic Violence Act, 2005

The PWDVA provides a robust framework of remedies for victims of domestic violence, addressing their safety, financial stability, and well-being. Key reliefs include:

Protection Orders: As per Section 18, orders are aimed at ensuring the safety of the victim. A magistrate can issue a protection order prohibiting the abuser from committing further acts of violence, contacting the victim, or entering her place of employment or residence. The respondent can also be prohibited from alienating joint property or causing harm to dependents or others assisting the victim.[5]

Residence Orders: According to Section 19 of the Act recognizes the victim's right to reside in the shared household, preventing the respondent from dispossessing her or disturbing her possession. In cases where continued cohabitation with the respondent is unsafe, the court can order the respondent to vacate the household or provide alternative accommodation for the victim.[6]

Monetary Relief: Section 20 of the Act provides for, financial independence is critical for victims of domestic violence, especially those who may be economically dependent on the abuser. The court can order the respondent to provide monetary relief to cover expenses related to loss of earnings, medical treatment, or damage to property. This includes compensation for emotional distress, allowing victims to regain stability.[7]

Custody Orders: Section 21 stipulates that, in cases where children are involved, the magistrate can grant temporary custody to the aggrieved person, ensuring that their welfare is protected. Visitation rights for the respondent can be restricted if deemed harmful to the children.[8]

Breach of Protection Orders: Section 31 of the Act addresses the consequences of breaching protection orders. A breach is treated as a cognizable and non-bailable offence, punishable with up to one year of imprisonment or a fine of Rs. 20,000, or both. The aggrieved person can report the breach to the Protection Officer, who will forward it to the Magistrate or police for further action.[9]

Protection Officers

Protection Officers are pivotal in ensuring that victims of domestic violence receive timely relief and support. Their appointment and duties are outlined under Sections 2(n), 4, 8, and 9 of the PWDVA, as well as the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Rules, 2006.

a) Appointment and Role of Protection Officers (Section 8)[10] - Protection Officers are appointed by the State Government. Their primary function is to assist the Magistrate and the victim in the discharge of responsibilities under the Act.

b) Duties of Protection Officers (Section 9[11] & Rule 8[12])

The Protection Officer’s responsibilities include:

Filing Domestic Incident Reports (DIRs): On receiving a complaint, the Protection Officer prepares a DIR (Form I) and submits it to the Magistrate.

Legal assistance: They help the victim access legal aid, file applications for protection orders, and assist in ensuring the implementation of orders for monetary relief.

Shelter and medical aid: Protection Officers ensure that the aggrieved person has access to a shelter home and medical facilities.

Coordinating with service providers: Protection Officers liaise with service providers, such as shelters, counselors, and legal aid services, to offer support to the victim.

Domestic Incident Reports (DIRs)

The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005 (PWDVA) introduces a crucial document known as the Domestic Incident Report (DIR). Section 2(e) of the Act defines a DIR as "a report made in the prescribed form on the receipt of a complaint of domestic violence from an aggrieved person."[13] This prescribed form, detailed in Form I of the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Rules (PWDVR), provides a clear and convenient format for recording incidents of domestic violence.

A DIR serves a function similar to that of a First Information Report (FIR) in criminal law, acting as a public record of a complaint. Protection Officers (POs) are mandated to record a DIR upon receiving a domestic violence complaint. The process of recording a DIR is designed to be accessible and supportive of the aggrieved person. In cases where the complainant is illiterate or otherwise incapacitated, the PO must assist in filling out the DIR, explain its contents, and obtain the person's signature or thumb impression. The PO is required to provide a free copy of the original DIR to the aggrieved person in all cases.

For individuals capable of filling out the DIR independently, POs are advised to offer guidance on its content and proper information recording. It's important to note that a DIR is intended to be an accurate record of the complaint, not an investigative report. While POs aren't required to conduct inquiries when recording a DIR, they must ensure that it is completed meticulously and accompanied by all relevant supporting documents.

The recording of a DIR does not automatically initiate judicial or investigative processes. It serves primarily as a public record of a domestic violence complaint. Judicial proceedings only commence if the aggrieved person chooses to pursue them by filing an application under Section 12 of the PWDVA in court.[14] The DIR must be attached to any such application.

Even if no application is filed, POs are obligated to forward all recorded DIRs to the Magistrate with jurisdiction over the area where the alleged domestic violence occurred. Magistrates are required to consider all DIRs received from a PO before issuing any orders under the PWDVA. This consideration may include not only the DIR filed with an application but also any DIRs forwarded by the PO on previous occasions. As a public record, the DIR serves as valuable evidence of past incidents of domestic violence.

It's worth noting that an aggrieved person has the option to approach the court directly with an application under Section 12, without a DIR. In such cases, the Magistrate may instruct the PO to record and file a DIR if the application lacks sufficient details or if no DIR has been previously recorded and forwarded. However, in some instances, the Magistrate may proceed with the case without a DIR if deemed unnecessary.

The PWDVA also empowers registered Service Providers (SPs) and notified medical facilities to receive domestic violence complaints and record DIRs. In these cases, both SPs and medical facilities must forward a copy of the DIR to the PO.

A DIR should be recorded whenever an aggrieved person approaches a PO with a domestic violence complaint, regardless of whether they intend to file a PWDVA application. Furthermore, an aggrieved person has the right to record separate DIRs for each distinct incident of domestic violence if they choose to do so.

This comprehensive approach to documenting domestic violence incidents through DIRs aims to create a robust system of record-keeping, ensuring that all complaints are properly documented and considered in any subsequent legal proceedings. By providing multiple avenues for recording DIRs and making the process accessible to all, the PWDVA seeks to empower victims of domestic violence and facilitate their access to justice.[15]

Criminal Provisions Complementing Domestic Violence Laws

Apart from the PWDVA, the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS),2023 contains several provisions aimed at preventing domestic violence and providing justice for victims:

Cruelty by Husband or Relatives: Section 85 of BNS criminalizes cruelty towards women in marital relationships, particularly those related to dowry demands or actions that endanger the victim’s life or health. The husband or relative of the husband subjecting a woman to cruelty can be punished with imprisonment up to three years and a fine. Cruelty is defined as: a) Willful conduct likely to drive the woman to suicide or cause grave injury or danger to her life, limb, or health (mental or physical) b) Harassment related to demands for dowry or property.[16]

Dowry Death: Section 80 of BNS presumes the guilt of the husband or his relatives in cases where a woman dies under suspicious circumstances within seven years of marriage following dowry-related harassment. When a woman dies from burns, bodily injury, or under unnatural circumstances within seven years of marriage, and there's evidence of cruelty or harassment related to dowry demands shortly before her death, it's considered a "dowry death." The husband or relative is deemed to have caused her death. The punishment is imprisonment for a minimum of seven years, which may extend to life imprisonment.[17]

Presumption as to abetment of suicide by a married women: Section 117 of Bharatiya Sashay Adhiniyam (BSA) establishes a presumption of abetment of suicide if a woman commits suicide within seven years of marriage and has been subjected to cruelty by her husband or in-laws. This presumption places a burden on the accused to prove their innocence, providing additional protection to the victim.[18]

Criminal provisions within Indian law significantly complement domestic violence legislation by providing legal remedies for various forms of abuse, neglect, and violence within familial relationships. These provisions are integral in ensuring justice for victims of domestic violence, particularly women, by offering both civil and criminal recourse. Below is a detailed discussion of how different provisions from the Code of Criminal Procedure, Indian Penal Code, and the Indian Evidence Act align with domestic violence laws to ensure comprehensive protection and enforcement.

Maintenance (Section 125 of the CrPC)

Under Section 125[19] of the CrPC, the law addresses the economic neglect of wives, children, and parents by providing them with a legal avenue to seek maintenance. This provision is crucial in cases where domestic violence victims, particularly women, face economic deprivation after leaving their abusive households or while still living in a shared household. Section 125(1) allows a Magistrate of the first class to order a person who has sufficient means but neglects or refuses to maintain his wife, children, or parents to provide financial support. This provision includes legitimate or illegitimate minor children and adult children who, due to physical or mental disabilities, are unable to support themselves. Notably, the law also extends to the maintenance of aged parents who are unable to maintain themselves.

A significant aspect of this provision is that it allows for interim maintenance while proceedings are ongoing, ensuring that the victim is not left destitute during lengthy court procedures. The maintenance provided under this section is not solely confined to final orders but can be granted as interim relief, ensuring timely assistance. Furthermore, the section also allows for expedited disposal of maintenance applications, mandating that these applications be addressed within 60 days of receiving notice.

This maintenance provision serves as a complementary remedy to the monetary reliefs granted under the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005. While the DV Act provides for economic relief specifically in cases of domestic violence, Section 125 CrPC serves a broader purpose, addressing general neglect within familial relationships. Both frameworks work in tandem to ensure that women and children who are victims of neglect or abuse receive the necessary financial support to maintain themselves.

Domestic Violence as defined in Case Laws

Several landmark cases in India have shaped the judicial understanding of domestic violence and expanded the protection offered under the PWDVA:

Sandhya Manoj Wankhade v. Manoj Bhimrao Wankhade, 2011

In Sandhya Manoj Wankhade v. Manoj Bhimrao Wankhade, the Supreme Court clarified that domestic violence complaints can be filed against both male and female relatives, making it clear that the scope of the term "relative" is inclusive and not restricted to males.[20]

D. Velusamy v. D. Patchaiammal, 2010

D. Velusamy v. D. Patchaiammal was a pivotal case in defining "relationships in the nature of marriage" under the PWDVA. The Court emphasized that not all live-in relationships qualify for protection under the Act. To determine whether a relationship resembles a marriage, the couple must present themselves as spouses to society, cohabit for a significant period, and meet the legal age and criteria for marriage. The court specifically excluded casual relationships from this definition, focusing on those that exhibit permanency and mutual intent to form a life together.[21]

Indra Sarma v. VKV Sarma, 2013

In Indra Sarma v. VKV Sarma, the Supreme Court laid out further guidelines to assess whether a live-in relationship qualifies as one "in the nature of marriage." The court considered factors like the duration of cohabitation, financial arrangements, and whether the parties intended to share a household and life as partners. The existence of children and public socialization as a couple were also seen as important indicators of a relationship’s legitimacy. However, the Court also clarified that if one party is already married, the relationship cannot be considered as akin to marriage, thereby denying the aggrieved person relief under the PWDVA in such cases.[22]

Satish Chandra Ahuja v. Sneha Ahuja, 2021

In Satish Chandra Ahuja v. Sneha Ahuja, the Supreme Court redefined the concept of a "shared household." The court expanded the understanding of what constitutes a shared household to include any property where the woman has lived with her husband or in-laws, broadening the scope of protection available to women in domestic relationships. This judgment overruled previous restrictive interpretations and allowed women more security in asserting their rights to residence.[23]

International Experience

Internationally, several conventions and agreements have set the standard for combating domestic violence. The Council of Europe’s Istanbul Convention defines domestic violence as all acts of physical, sexual, psychological, or economic violence within the family or between partners, regardless of whether they share a residence. It emphasizes the need for protective measures that ensure the safety and dignity of victims.

Another key international instrument is the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), which India ratified in 1993. CEDAW’s Recommendation No. 12 outlines the obligations of member states to enact laws and policies aimed at preventing violence against women. This includes protecting women not only within the family but also in other social environments such as workplaces. States are urged to provide support services, collect data on violence, and report on their efforts to curb such abuse.

Appearance in official databases

National Commission for Women

The National Commission for Women on its official website receives complaints for various crimes committed against women. The statistics relating to the complaints received by the National Commission for women are also available on the website. This includes various types of crimes including cases filed under the Protection of Women against Domestic Violence Act.

National Crime Records Bureau

Another body which provides extensive data related to the case filed under the Protection of Women against Domestic Violence Act is the National Crime Records Bureau. The NCRB publishes a yearly publication called Crime in India. One of the issues covered are the cases under the Protection of Women against Domestic Violence Act. The publication studies various data points relating to domestic violence ranging from the number of cases being investigated to the number of cases being reported to the police and cases pending before the various courts.[24]

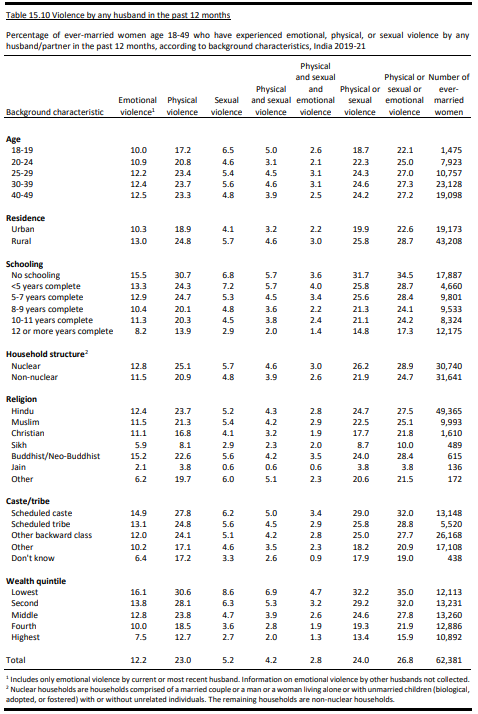

2019-21 India National Family Health Survey

Chapter 15 of the National Family Health Survey (NFHS) focuses on domestic violence, providing a detailed analysis of its prevalence and impact on women in India. It covers key areas such as the measurement of violence, women’s experiences of physical and sexual violence, and identifies the perpetrators of these acts. The chapter examines various forms of violence, including spousal violence, detailing both the physical and emotional abuse women face. It also explores marital control by husbands and the injuries women suffer due to spousal violence. Additionally, it acknowledges violence initiated by women against husbands, offering a broader view of domestic violence dynamics. The survey also looks into help-seeking behaviors among women, investigating how many seek support and where they turn for help, including both informal sources (family, friends) and formal institutions (police, NGOs).[25]

Research that engages with domestic violence

Research on domestic violence in India has garnered significant attention, with several research centers and organizations dedicating their efforts to exploring its prevalence, causes, risk factors, and intervention strategies. Various projects are also focused on assessing the effectiveness of legal frameworks, especially the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005 (PWDV Act), in combating this issue. The following are key research centers and their notable contributions to understanding domestic violence in India.

Status Report Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act 2005 (UP) (AALI)

A Status Report compilation of case studies on violence against women who have asserted their right to choose their relationships. The case studies document the experiences and struggles of women and their partners trying to navigate familial violence and the justice system.[26]

Securing Justice: Status of Implementation of the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005 in Uttar Pradesh (Years 2015 to 2019) (AALI)

The research report attempts to assess the effectiveness of the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005 (PWDV Act, 2005) in the state of Uttar Pradesh between the years 2015 and 2019. A prior study to assess the status of implementation of the PWDV Act, 2005 in Uttar Pradesh was undertaken by AALI in the year 2010 which was updated in the year 2014. While some headway was made in terms of improving infrastructure support, training-capacity building, and stakeholder convergence based on the recommendations made in the previous report, the progress has been much slower than expected. The findings in this report suggest that while the usage of the law has grown manifold since we conducted the last status study, its effectiveness remains limited because fundamental, structural, and procedural issues remain unaddressed. The findings also capture voices of women survivors of domestic violence who have used the PWDV Act, 2005 to seek relief and have experienced the challenges of the justice system first-hand. The report makes actionable recommendations for the state and the judiciary to take steps that can address existing gaps and lead to complete realization of women’s rights as envisioned in the law.[27]

Realizing Rights: Status of Implementation of the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005 in Jharkhand (Years 2015 to 2019) (AALI)

The research report attempts to assess the effectiveness of the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005 (PWDV Act, 2005) in the state of Jharkhand between the years 2015 and 2019. It has been more than fifteen years since the law was brought into effect during which no large-scale studies have been undertaken to evaluate the effectiveness of the law in the state. Findings of the study show that the support systems remain divergent and dysfunctional, the process of filing DIRs and passing orders is bogged down by systemic lag, and execution of orders remains poor. The report aims to document these gaps and challenges in implementation of the special law in the state. Findings capture voices of women survivors of domestic violence who have used the PWDV Act, 2005 to seek relief and have experienced the challenges of the justice system first-hand. The report makes actionable recommendations for the state and the judiciary to take steps that can address existing gaps and lead to complete realization of women’s rights as envisioned in the law.[28]

A Study on the Status of Implementation of Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005 in Odisha (CLAP India)

In collaboration with Oxfam India, CLAP- Legal Service Institute conducted an in-depth study titled "A Study On Status Of Implementation Of Protection Of Women From Domestic Violence Act, 2005 In Odisha."[29] This research was aimed at unraveling the realities faced by women who are victims of domestic violence in Odisha. It focuses on understanding the on-ground functioning of various institutions established under the PWDV Act, such as Protection Officers, Magistrates, Lawyers, NGOs, Service Providers, Police, and Shelter Homes. By including the perspectives of key stakeholders, as well as the aggrieved women themselves, the study provides a comprehensive view of the practical challenges and gaps in service delivery and law enforcement at the field level.

Domestic Violence in India Series (ICRW)

The ICRW has conducted extensive studies on domestic violence, particularly through a three-year research program in collaboration with Indian academic institutions and non-governmental organizations. This program included a household study conducted in rural Gujarat, which explored trends of domestic violence, as well as intervention studies that documented the responses to this issue. ICRW's research plays a pivotal role in understanding the broader social and cultural factors influencing domestic violence in India, while also assessing the effectiveness of various interventions aimed at addressing these problems. The five research studies under taken under this program are

- Summary Report Part 1: This report summarises three studies: a household study by Leela Visaria that enumerates and elucidates trends of domestic violence in rural Gujarat and provides a backdrop to the intervention studies;[30] and two studies, one by Nishi Mitra and the other by Veena Poonacha and Divya Pandey, that document and analyze the range of organized responses to domestic violence against women being implemented by the state and non-governmental sectors in India.[31]

- Summary Report Part 2: This report summarizes four studies that examined hospitals, nongovernmental organizations, law enforcement and judicial systems, which are all key entry points for women experiencing domestic violence. The studies examine institutional discourse and also provide data about patterns and trends of domestic violence in India. These studies are:

- Summary Report Part 3: This report summarises the large multi-site household survey conducted by the International Clinical Epidemiologists Network to estimate domestic violence prevalence in India and to increase understanding of domestic violence correlates and outcomes.

- Summary Report Part 4: This report summarizes four studies exploring the links between masculinity and domestic violence as well as an aggregate analysis undertaken by ICRW on these linkages. These studies are:

- Masculinity and Violence Against Women in Marriage: An Exploratory Study in Rajasthan[36]

- Masculinity and Domestic Violence in a Tamil Nadu Village[37]

- Gender Violence and Construction of Masculinities: An Exploratory Study in Punjab[38]

- Masculinity and Violence in the Domestic Domain: An Exploratory Study Among the MSM Community[39]

- Links Between Masculinity and Violence: Aggregate Analysis[40]

- Summary Report part 5: This report summarizes three studies documenting and assessing the impact of three innovative women-initiated community-level responses to domestic violence. These studies are:

- The Shalishi in West Bengal: A Community Response to Domestic Violence

- Women-Initiated Responses to Domestic Violence in Uttar Pradesh A Study of the Nari Adalat and Sahara Sangh

- Women-Initiated Responses to Domestic Violence in Gujarat: A Study of the Nari Adalat and Mahila Panch

Guides and Manuals

Ending Domestic Violence Through Non-Violence: A Manual for PWDVA Protection Officers. (LCWRI)

The Lawyers Collective Women’s Rights Initiative has published a comprehensive manual titled "Ending Domestic Violence Through Non-Violence: A Manual for PWDVA Protection Officers." This manual aims to equip Protection Officers with the necessary tools and knowledge to effectively carry out their duties under the PWDV Act.[41] Designed for a non-legal audience, it simplifies the procedures and processes under the Act, making it easier for Protection Officers and other stakeholders to navigate the legal system. LCWRI's efforts in creating user-friendly resources have significantly improved the capacity of Protection Officers to deliver services effectively and in a timely manner.

Safety support and solutions - a guide to support survivors of domestic violence. (iProbono)

The guide "Safety, Support, and Solutions: A Comprehensive Resource for Empowering Domestic Violence Survivors" is a valuable tool for both survivors and the individuals or organizations supporting them.[42] Created by iProbono, it addresses legal, social, and emotional aspects of survivor assistance, focusing on providing rights-based and trauma-informed care. This guide offers detailed guidance on how to seek help from protection officers, access shelters or legal assistance, and navigate legal procedures outlined in laws such as the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act of 2005. In addition, it clarifies the responsibilities of various stakeholders including police officers, protection officers, shelter facilities, counselors, and legal aid providers. This resource is designed not only for survivors but also for community workers, attorneys, and members of civil society.

References

- ↑ Emery, Clifton R.(2011) Disorder or deviant order? Re-theorizing domestic violence in terms of order, power and legitimacy: A typology, Aggression and Violent Behavior, Volume 16, Issue 6.

- ↑ See Domestic Violence, Office on Violence Against Women, US Department of Justice available at https://www.justice.gov/ovw/domestic-violence.

- ↑ See Section 85, Bharatiya Nyay Sanhita, 2023.

- ↑ See Section 498A of the Indian Penal Code, 1862.

- ↑ See Section 18, The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005

- ↑ See Section 19, The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005.

- ↑ See Section 20, The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005.

- ↑ See Section 21, The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005.

- ↑ See Section 31, The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005.

- ↑ See Section 8, The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005.

- ↑ See Section 9, The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005.

- ↑ See Rule 8, The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Rules, 2006.

- ↑ See Section 2(e), The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005.

- ↑ See Section 12, The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005.

- ↑ See Chapter VI, Ending Domestic Violence Through Non-Violence: A Manual for PWDVA Protection Officers, Protection of Women from Domestic Violence, The Lawyers Collective Women’s Rights Initiative available at Ending Domestic Violence Through Non-Violence: A Manual for PWDVA Protection Officers.

- ↑ See Section 498A, Indian Penal Code, 1860.

- ↑ See Section 304B, Indian Penal Code, 1860.

- ↑ See Section 113A, The Indian Evidence Act, 1872.

- ↑ See Section 125, Criminal Procedure Code, 1973.

- ↑ See Sandhya Manoj Wankhade v. Manoj Bhimrao Wankhade, (2011) 3 SCC 650, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/134989405/

- ↑ See D. Velusamy v. D. Patchaiammal, (2010) 10 SCC 469, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1521881/

- ↑ Indra Sarma v. V.K.V. Sarma, (2013) 15 SCC 755, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/192421140/

- ↑ See Satish Chandra Ahuja v. Sneha Ahuja, 2021 1 SCC 414, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/62368827/

- ↑ See Chapter15 of the Crime in India 2022, Statistics Vol 1, National Crime Records Bureau.

- ↑ International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ICF. 2021. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5), 2019-21: India. Mumbai: IIPS

- ↑ See Status Report, Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005- Uttar Pradesh (2006-2012), Association For Advocacy and Legal Initiative.

- ↑ See Securing Justice: Status of Implementation of the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act,2005 in Uttar Pradesh (Years 2015 to 2019), Association For Advocacy and Legal Initiative

- ↑ See Realizing Rights: Status of Implementation of the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005 in Jharkhand (Years 2015 to 2019), Association for Advocacy and Legal Initiatives Trust.

- ↑ See A Study On Status Of Implementation Of Protection Of Women From Domestic Violence Act, 2005 In Odisha, CLAP- Legal Service & Oxfam India. available at: https://www.clapindia.org/pdf/Research%20Report%20on%20DV%20Act%202005.pdf

- ↑ Violence against Women in India: Evidence from Rural Gujarat Leela Visaria Gujarat Institute of Development Studies Best Practices among Responses to Domestic Violence in Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh

- ↑ Nishi Mitra Women’s Studies Unit Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai Responses to Domestic Violence in Karnataka and Gujarat Veena Poonacha and Divya Pandey Research Centre for Women’s Studies (RCWS), and SNDT Women’s University, Mumbai

- ↑ Health Records and Domestic Violence in Thane District, Maharashtra; Surinder Jaswal, Department of Medical and Psychiatric Social Work Tata Institute of Social Sciences

- ↑ Domestic Violence: A Study of Organizational Data; Sandhya Rao, Indhu S., Ashima Chopra, and Nagamani S.N., Researchers Dr. Rupande Padaki, Consultant Hengasara Hakkina Sangha (HHS)

- ↑ Special Cell for Women and Children: A Research Study On Domestic Violence; Anjali Dave and Gopika Solanki Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai

- ↑ Patterns and Trends of Domestic Violence in India: An Examination of Court Records; V. Elizabeth Centre for Women and Law National Law School of India University, Bangalore

- ↑ Masculinity and Violence Against Women in Marriage: An Exploratory Study in Rajasthan; Ch. Satish Kumar S.D. Gupta George Abraham Indian Institute of Health Management Research, Jaipur

- ↑ Masculinity and Domestic Violence in a Tamil Nadu Village; Anandhi. S. J. Jeyaranjan Institute for Development Alternatives (IDA), Chennai

- ↑ Gender Violence and Construction of Masculinities: An Exploratory Study in Punjab; Rainuka Dagar Institute for Development Communication, Chandigarh

- ↑ Masculinity and Violence in the Domestic Domain: An Exploratory Study Among the MSM Community; P.K. Abdul Rahman The Naz Foundation (I) Trust, New Delhi

- ↑ Links Between Masculinity and Violence: Aggregate Analysis; Nata Duvvury Madhabika Nayak Keera Allendorf International Center for Research on Women, Washington, D.C.

- ↑ Lawyers Collective Women’s Rights Initiative (LCWRI) (n.d.) Ending Domestic Violence Through Non-Violence: A Manual for PWDVA Protection Officers. Lawyers Collective, https://lawyerscollective.org/index.php/womens-right/

- ↑ iProbono (n.d.) Safety, Support and Solutions: A Guide to Support Survivors of Domestic Violence. https://i-probono.in/download/?id=8572