Election Petition

What is an 'Election Petition'?

An election petition is the legal process to challenge the validity of an election. The Constitution of India under Article 329(b) prescribes that an election to either House of the Parliament or of a state legislature can be challenged in a manner provided by the law. Pursuant to the constitutional mandate, necessary provision for election petitions have been made under the Representation of the People Act, 1951[1] and Presidential and Vice Presidential Elections Act, 1952.

An election petition is the sole legal remedy available to a voter or candidate who believes there has been malpractice in an election to the Parliament, state legislature, or local government. To challenge the result, the individual must file an election petition with the High Court of the state where the constituency is located. This petition must be submitted within 45 days from the date of the poll results; courts will not entertain petitions filed after this period and these petitions shall ideally be disposed within the six months of filing.[2] Election Petitions under Part III of the Presidential and Vice Presidential Elections Act, 1952 are filed directly in the Supreme Court.

Official Definition of 'Election Petition'

Election Petition as defined in Legislations

Article 329(b) of the Constitution of India as amended by the Constitution (19th Amendment) Act, 1966, provides that notwithstanding anything in the Constitution, no election to either House of Parliament or the Legislature of a State shall be called into question except by an election petition presented to such authority and in such manner as may be provided for by or under any law made by the appropriate Legislature.

The Representation of the People Act, 1951, furthers this clause as it empowers the high courts to hear and decide election petitions. Section 80 of the Representation of the People Act, 1951, states that “no election shall be called in question except by an election petition presented in accordance with the provisions of Part VI of the Act, that deals with Disputes regarding Elections”. Section 80, which is drafted in almost the same language as Article 329(b), provides that “no election shall be called in question except by an election petition presented in accordance with the provisions of this Part”. Section 100 provides for the grounds on which an election may be called in question. An election petition, as defined by the The Representation of the People Act, 1951, is the exclusive legal method to challenge election results. Article 329 of the Constitution prohibits any other form of proceedings to set aside an election. Thus, only an election petition, filed according to the prescribed manner and authority, is allowed for contesting election outcomes.

The Constitution (19th Amendment) Act, 1966, abolished the jurisdiction of Election Tribunal over election disputes. The Amendment has vested this power in the High Courts. The effect of vesting the power in the High Courts was to expedite decision in election disputes.

The Representation of the People Act, 1951

Jurisdiction

The authority to try election petitions is vested on the High Court. The jurisdiction is typically exercised by a single Judge of the High Court. The Chief Justice has the power to assign one or more Judges to handle election petitions. In High Courts with only one Judge, that Judge will try all election petitions. The High Court has the discretion to try an election petition, wholly or partially, at a location other than the seat of the High Court if it serves the interests of justice or convenience.[3]

Procedure

An election petition challenging an election can be presented to the High Court by any candidate or elector within forty-five days from the date of election of the returned candidate.[4] A "returned candidate" is someone whose name has been published as a duly elected candidate. The term "elector" includes anyone entitled to vote at the election, whether they voted or not. The petition must be accompanied by as many copies as there are respondents mentioned, each attested by the petitioner as true copies.

Parties to the Election Petition

A petitioner must include all contesting candidates, except themselves if seeking a declaration that any returned candidate's election is void and simultaneously claiming another candidate's election. Alternatively, if solely seeking to void a returned candidate's election, all returned candidates must be included as respondents. Any candidate implicated in allegations of corrupt practices must also be joined as a respondent.[5]

Contents of the Election Petition

An election petition must contain a concise statement of material facts and full particulars of any corrupt practice alleged. It should include names, dates, and places relevant to the corrupt practices, be signed by the petitioner, and verified as per the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908. If corrupt practices are alleged, the petition must be accompanied by an affidavit supporting these allegations and particulars.[6] In terms of relief, the petitoner can seek an declaration that the election of all or any of the returned candidates is void, claim a further declaration that he himself or any other candidate has been duly elected.[7]

Trial of Election petition

Section 86 of the The Representation of the People Act, 1951 outlines the procedural framework for the trial of election petitions before the High Court:

- Dismissal Criteria: The High Court shall dismiss any election petition that fails to comply with the procedural requirements specified in sections 81, 82, or 117 of the Act. Such dismissals are deemed as orders under section 98(a).[8]

- Assignment of Judge: Upon presentation, the election petition is promptly assigned to a Judge designated by the Chief Justice for election petition trials under section 80A(2).[9]

- Consolidation of Petitions: If multiple petitions arise from the same election, they are consolidated and tried together by the same Judge, who may choose to handle them separately or in groups.[10]

- Joining of Respondents: Any candidate not initially named as a respondent has the right to apply within fourteen days from the trial's commencement to be included, subject to the High Court's orders on costs.[11]

- Amendment of Allegations: The High Court may permit amendments to the particulars of alleged corrupt practices in the petition to ensure a fair trial, provided such amendments do not introduce new corrupt practices not previously alleged.[12]

- Trial Continuity: The trial of an election petition is to be conducted continuously from day to day, unless adjournment beyond the next day is necessary, with reasons recorded.[13]

- Trial Timeline: Every effort is made to conclude the trial within six months from the date the election petition is presented to the High Court, aiming for expeditious resolution.[14]

The trial of an election petition by the High Court should follow, as closely as possible, the procedure for the trial of suits under the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908. The High Court has the discretion to refuse to examine any witness if their evidence is not material to the decision of the petition or if it appears the witness is being presented frivolously or to delay proceedings. The provisions of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872, apply to the trial of election petitions.[15]

Procedural and Evidentiary Rules

The evidentiary requirements under election petitions are relaxed, allowing court consideration of public records and electoral roll entries as evidence of their stated facts.[16] The secrecy of voting is strictly upheld, prohibiting compulsory disclosure of one's vote except in cases involving accusations of electoral bribery.[17] Witnesses who may incriminate themselves by their testimony are protected from prosecution, except for perjury, and courts may grant certificates of immunity to these witnesses.[18] Additionally, the court can order reasonable expenses for witnesses summoned to testify.[19]

Substantive Judicial Powers and Grounds for Annulment

The High Court has broad authority in election petitions, including permitting the declared candidate to challenge claims made by petitioners or other candidates.[20] At the conclusion of the trial, the court must either dismiss the petition, declare the election void, or declare an alternative candidate duly elected along with voiding the election.[21] When corrupt practices are established, the court must specify the nature of the offence, name all guilty parties (including non-parties who were notified), and provide those named an opportunity to respond.[22]

Grounds for Declaring Election Void and Related Procedures

Section 100 of the The Representation of the People Act, 1951 enumerates several critical grounds upon which the High Court may declare an election void. The election of a particular candidate can be declared void under section 100 of the Representation of People Act, 1951, if the High Court is of the opinion that -

- a) On the date of his election a returned candidate was not qualified or was disqualified to be chosen to fill the seat.

- b) Any corrupt practice (under Section 123) has been committed by a returned candidate or his election agent or by any other person with the consent of a returned candidate or his election agent.

- c) By improper acceptance of any nomination.

- d) By any improper reception, refusal or rejection of any vote or the reception of any vote which is void.

- e) By any non-compliance with the provisions of the Constitution or RPA or any rules or orders made under this act.

Furthermore, the court has power to declare a candidate other than the returned candidate duly elected if it is satisfied that such candidate received the majority of the valid votes cast[23] i.e. parties to election petition can request a declaration that they or another candidate be duly elected if they received a majority of valid votes, or if, after excluding votes obtained by corrupt practices, they would have received the majority of valid votes.

In cases where there is a tie in votes between candidates during the trial of an election petition, Initially, any decision on the tie made by the returning officer under electoral laws will be considered binding for the petition's purposes. If the returning officer's decision does not resolve the tie completely, the High Court will then decide between the tied candidates by lots.[24] In cases where the votes for two or more candidates are equal, the law prescribes procedures for determining the successful candidate, including the possibility of drawing lots, unless the High Court orders a fresh election. Finally, the High Court is required to communicate the orders passed in an election petition to the Election Commission and other appropriate authorities to ensure further necessary action and publication of the decision.[25]

Withdrawal, Abatement, and Appeals in Election Petitions

Petitions can be withdrawn only with the High Court’s permission, following a prescribed procedure, and the withdrawal is reported to the Election Commission for record-keeping.[26] The law also deals with abatement of petitions in cases such as death of petitioners, with provisions for substitution to continue proceedings where possible.[27]

Section 116A provides that appeals on High Court decisions can be made to the Supreme Court on questions of law or fact. Appeals must be filed within thirty days of the High Court's order, with the Supreme Court having the discretion to allow appeals filed after this period if there is sufficient cause. Under Section 116B applications can be made to the High Court for a stay of operation of its order before the expiration of the appeal period. The Supreme Court can also stay the operation of such orders if an appeal is preferred. A stay order renders the High Court's order ineffective until further notice, and the stay must be communicated to the Election Commission and relevant parliamentary or legislative authorities.

Security for Costs and Costs Orders

Security for costs is a mandatory requirement in election petitions to ensure that parties pay the costs of the process, with provisions authorizing the High Court to order further security from respondents when necessary. When a petitioner presents an election petition, they are required to deposit a sum of two thousand rupees as security for costs.[28] The amount of two thousand rupees serves as an initial deposit, but the High Court retains the authority to demand additional security at any point during the trial if deemed necessary to cover anticipated costs.

Costs incurred in election petition proceedings are at the discretion of the court, including provisions for payment of such costs out of security deposits and appropriate enforcement mechanisms for cost orders.[29]

Election Petition as defined in case law(s)

Scope of Eection petiton

Hari Vishnu Kamath v. Syed Ahmad Ishaque

In the case of Hari Vishnu Kamath v. Syed Ahmad Ishaque (1954) 2 SCC 881, it was held that, "on a plain reading of the article (Article 329 of the Constitution), what is prohibited therein is the initiation of proceedings for setting aside an election otherwise than by an election petition presented to such authority and in such manner as provided therein. A suit for setting aside an election would be barred under this provision." An election petition is a legal mechanism provided under the RP Act, to challenge the validity of an election on specific grounds. It allows a voter or candidate to contest the election results if there are allegations of malpractice, such as the improper rejection of a nomination paper. The definition of "election" in this context can be interpreted broadly, covering the entire electoral process, or narrowly, focusing on the final selection of a candidate. This petition must be filed within a specified timeframe (45 days from the poll results), and only through this legal channel can an election be questioned.

N.P. Ponnuswami v. Returning Officer, Namakkal Constituency

In the case of N.P. Ponnuswami v. Returning Officer, Namakkal Constituency[30] , it was held that, “As we have seen, the most important question for determination is the meaning to be given to the word "election" in Article 329(b). That word has by long usage in connection with the process of selection of proper representatives in democratic institutions, acquired both a wide and a narrow meaning. In the narrow sense, it is used to mean the final selection of a candidate which may embrace the result of the poll when there is polling or a particular candidate being returned unopposed when there is no poll. In the wide sense, the word is used to connote the entire process culminating in a candidate being declared elected.”[31]

"The next important question to be considered is what is meant by the words “no election shall be called in question”. A reference to any treatise on elections in England will show that an election proceeding in that country is liable to be assailed on very limited grounds, one of them being the improper rejection of a nomination paper. The law with which we are concerned is not materially different, and we find that in Section 100 of the RP Act, one of the grounds for declaring an election to be void is the improper rejection of a nomination paper."

Senthilbalaji V. v. A.P. Geetha

In Senthilbalaji V. v. A.P. Geetha,[32] The Supreme Court observed that “The consensus of judicial opinion is that the failure to plead material facts concerning alleged corrupt practice is fatal to the election petition. The material facts are the primary facts which must be proved on trial by a party to establish the existence of a cause of action.” It was further said in the case that, “Before we consider various paragraphs of the election petition to determine the correctness of the High Court order we think it necessary to bear in mind the nature of the right to elect, the right to be elected and the right to dispute election and the trial of the election petition. Right to contest election or to question the election by means of an election petition is neither common law nor fundamental right, instead it is a statutory right regulated by the statutory provisions of the Representation of People Act, 1951.

“Section 83 lays down a mandatory provision providing that an election petition shall contain a concise statement of material facts and set forth full particulars of corrupt practice. The pleadings are regulated by Section 83 and it makes it obligatory on the election petitioner to give the requisite facts, details and particulars of each corrupt practice with exactitude. If the election petition fails to make out a ground under Section 100 of the Act it must fail at the threshold. Allegations of corrupt practice are in the nature of criminal charges, it is necessary that there should be no vagueness in the allegations so that the returned candidate may know the case he has to meet. If the allegations are vague and general and the particulars of corrupt practice are not stated in the pleadings, the trial of the election petition cannot proceed for want of cause of action. The emphasis of law is to avoid a fishing and roving inquiry. It is therefore necessary for the Court to scrutinize the pleadings relating to corrupt practice in a strict manner.”

K. Venkatachalam v. A. Swamickan

In K. Venkatachalam v. A. Swamickan[33], the Supreme Court has held that article 329(b) which bars interference of courts in electoral matters does not come into play in a case which falls under articles 191 and 193 which provides for disqualification of membership and penalty for sitting and voting when disqualified and the whole of election process is over. In such case, the High Court can interfere under article 226 and declare that he was not entitled to sit in the State Assembly.

Parties to Election Petition

Joyti Basu and Others vs. Debi Ghosal and Others

The Supreme Court of India, in the case of Joyti Basu and Others vs. Debi Ghosal and Others (Civil Appeal No. 1553 of 1980), delivered a significant judgment on the scope of parties in election petitions under the RP Act. In 1980, Mohammad Ismail, backed by the Communist Party of India (Marxist), won the parliamentary seat for 19-Barrackpore in West Bengal. Debi Ghosal, a rival candidate, filed an election petition alleging collusion and corrupt practices involving Ismail, Chief Minister Jyoti Basu, and two other West Bengal ministers. The High Court of Calcutta initially allowed Basu and the ministers to be joined as respondents in the petition, despite objections that they were not candidates in the election. Basu and the ministers appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing that under the Representation of the People Act, only candidates could be respondents to an election petition. The Supreme Court upheld their appeal, ruling that according to Section 82 of the RP Act, only candidates could be joined as respondents in an election petition. The Court emphasized that the Act provided a specific framework for election disputes, restricting parties to those directly involved in the electoral process. It noted that allowing non-candidates to be joined as respondents could lead to misuse and unnecessary legal complications, undermining public officials' ability to perform their duties effectively. This decision clarified the legal standing under Indian election law, ensuring that election petitions focus solely on candidates and adhere strictly to statutory provisions.

Election Petition as defined in official Government Reports

National Commission to review the working of the Constitution (NCRWC) Report

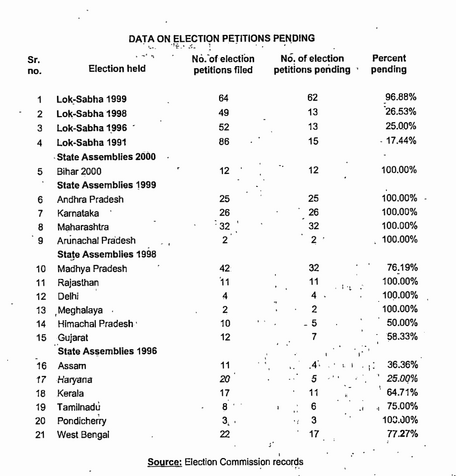

The NCRWC report noted that High Court is expected to give judgement on all election petitions within 6 months, but in actual practice, it takes much longer and often the petitions remain pending for years and in the meantime even the full term of the House expires. It relied on the data below and recommended that special court or special election benches designated for election petitions only should be formed in the High Court; For deciding the cases, these Courts should take evidence through Commissioners.[34]

Administrative Reform Commission (ARC) Report

The second ARC report on Ethics in Governance also recommended that Special Election Tribunals should be constituted at the regional level under Article 323B of the Constitution to ensure speedy disposal of election petitions and disputes within a stipulated period of six months. Each Tribunal should comprise a High Court Judge and a senior civil servant with at least 5 years of experience in the conduct of elections (not below the rank of an Additional Secretary to Government of India/Principal Secretary of a State Government). Its mandate should be to ensure that all election petitions are decided within a period of six months as provided by law. The Tribunals should normally be set up for a term of one year only, extendable for a period of 6 months in exceptional circumstances.[35] These tribunals, composed of a High Court Judge and a senior civil servant with extensive election experience, would ensure the speedy disposal of election petitions within six months. This dedicated judicial setup would alleviate the High Courts' burden, provide specialized expertise, and enhance the credibility and efficiency of the electoral justice system. Such tribunals, set up for one year with possible extensions in exceptional cases, would significantly improve the timely resolution of election disputes, reinforcing public confidence in the democratic process[36].

Law Commission Report

255th Report of the Law Commission

In Report No.255, on “Electoral Reforms” (2015) the Law Commission noted that the current system of filing election petitions in India has several drawbacks: the non-uniform and formalistic procedure for presenting petitions, inordinate delays in trial, and a system of appeals that makes an appeal almost automatic. Firstly, the procedure varies among High Courts, causing inconsistencies, particularly in states with shared High Courts or multiple benches. Secondly, Section 82 requires petitioners to include all contesting candidates, even those with no realistic chance of being declared elected, wasting time and resources. Thirdly, Section 86 mandates summary dismissal for non-compliance with Section 117's security deposit requirements, despite such non-compliance not necessarily hindering the trial's progression. Fourthly, election petitions often face significant delays, as noted by the 4th ARC Report on Ethics, which can render the petitions ineffective by the time they are resolved.

It suggested amendments to Sections 80A, 82, 86, and 117 of the RP Act to address these issues, including raising the security deposit from Rs. 2000 to Rs. 10,000 to reflect inflation. The current system of handling election petitions in India suffers from severe delays and procedural inefficiencies. Instances like the dissolution of the 15th Lok Sabha in 2014 led to the dismissal of 25 pending petitions, some of which had been languishing for nearly five years despite statutory provisions for expeditious resolution. The process is marred by continuous adjournments, low prioritization by High Courts, and automatic appeals that further stall proceedings, exemplified by cases like Sushma Swaraj's and P. Veldurai's. These delays undermine the purpose of election petitions, eroding voter trust and rendering the right to challenge electoral outcomes ineffective. Recommendations include strict adherence to the six-month trial timeline mandated by the RP Act, establishment of dedicated "election benches" in High Courts, and amendments to limit appeals to the Supreme Court to ensure timely resolution. Introducing time limits for passing orders post-argument and reforming appeal procedures under Section 116A are crucial to expediting justice in electoral disputes and restoring faith in the democratic process.[37]

Civil Society Reports

As part of National Consultation on Electoral Reforms initiated by the Ministry of Law and Justice, Government of India, in late 2010, the Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR), and National Election Watch (NEW)[38] submitted its recommendations for electoral reforms. It recommended taht the time provided for filing election expenses by contesting candidates should be reduced to 20 days so that the time available for filing election petitions would increase to 25 days. It also highlighted a need of legal sanction against losing candidates also for filing an election petition who are guilty of corrupt practice in terms of Section 123 of the The Representation of the People Act, 1951 .

Official Databases

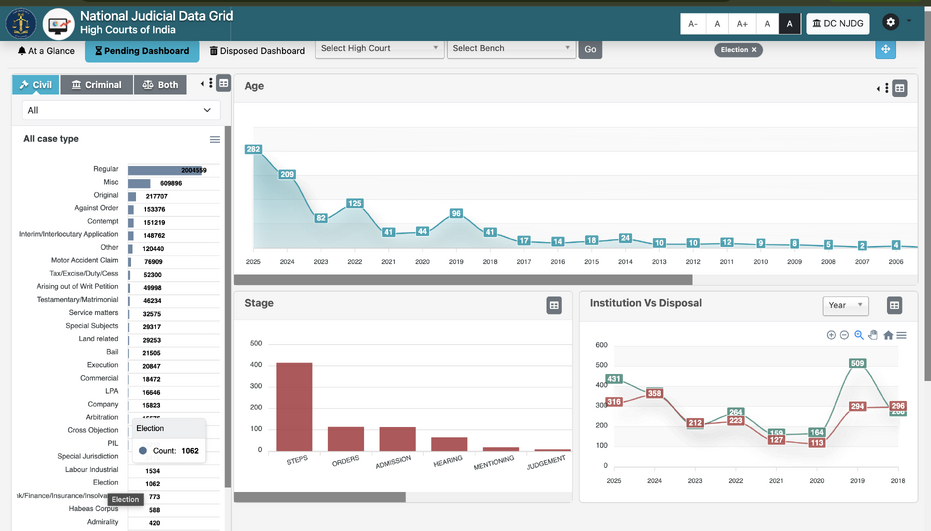

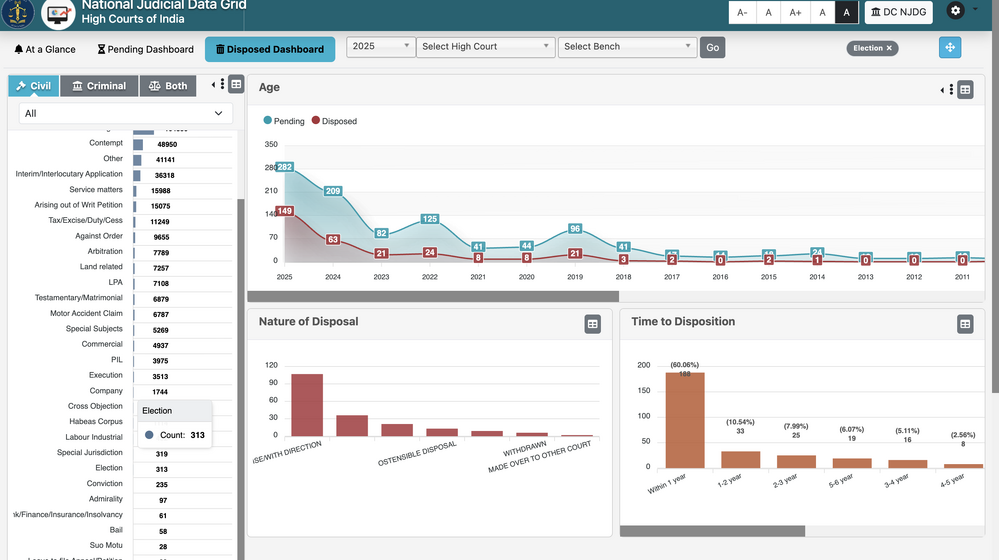

National Judicial Data Grid (NJDG) - High Courts

The National Judicial Data Grid (NJDG) (High Courts of India) maintains data for election petitions for each High Court, bench, and year. Election Petition is classified as a case type and the information related to pendency and disposal of election petition can be filtered accordingly for all High Courts or any particular High Court.

PENDING DASHBOARD

The data is further classified into age, stage, and institution v. disposal.

Disposed Dashboard

The data is further classified into age, nature of disposal, and time to disposition.

Case Types

Election Petitons are denoted through different accronyms across High Courts. Some of these include:

- EP - Punjab and Haryana High Court, Karnataka High Court

- E.P. - Patna High Court

- ELEP - Allahabad High Court

- EL. PET. - Delhi High Court

International Experiences

United States

State laws in the United States vary significantly regarding who can request and challenge vote counts and file election contests, as well as the circumstances and timeframes for these actions[39]. The laws specify who can request recounts, which often includes candidates, voters, or a designated number of voters within a specific jurisdiction. The grounds for requesting recounts commonly include a close vote margin, suspected errors in the count, or allegations of fraud or misconduct. States have specific deadlines by which recounts must be requested, often within a few days to a few weeks after the election. Similarly, the laws dictate who can file election contests, usually candidates or a specified number of voters, and the grounds for these contests might include fraud, errors, ineligible voters, or other irregularities affecting the outcome. Each state provides detailed procedures for filing and adjudicating election contests, including which courts or bodies have jurisdiction.

Candidates or electors must file a formal complaint or petition within the legal timeframe specified by the state. This typically requires presenting evidence of irregularities or violations of election laws that could have impacted the election outcome.[40] Once the complaint is filed, it is reviewed by the appropriate electoral or judicial authority. If the complaint is deemed credible, an investigation may be initiated to verify the claims. This process can involve recounts, audits, and hearings where evidence is presented and examined. If the investigation confirms significant irregularities or violations, the authority may take actions such as ordering a recount, annulling the election results, or even calling for a new election. The specific remedies available depend on the laws and regulations of the jurisdiction in question[41].

United Kingdom

The authors, Caroline Morris and Stuart Wilks-Heeg looked into “the Continuing Role and Relevance of Election Petitions in Challenging Election Results in the UK[42]”, examining the main criticisms of the current election petition process which include legal and financial barriers facing petitioners, the inability of returning officers to initiate petitions, and the assumption that election challenges are a private concern rather than a matter of public interest. The process is often lengthy, with even straightforward counting errors taking two to three months to be officially recognized and corrected. The high legal costs incurred by petitioners, often in the tens of thousands of pounds, can be a significant deterrent. These criticisms have been highlighted by various reviews and proposals for reform, including those by the Electoral Commission and the Law Commission, which have called for a more streamlined and accessible process for addressing administrative errors and electoral offenses.

Research that engages with 'Election Petition'

Adjudication of Election Petitions: How have courts fared (Justice Frustrated (2020))

This research article by Ritwika Sharma and Titiksha Mohanty[43] critically examines the functioning of Indian courts in adjudicating election petitions, focusing on statutory and judicial frameworks, their efficacy, and practical challenges. Its scope encompasses the legal foundations under the Representation of the People Act, 1951 and Article 329 of the Constitution, judicial roles in maintaining democratic integrity, and procedural bottlenecks in the trial and disposal of election petitions. The methodology combines statutory analysis and empirical data drawn from judicial orders of four High Courts and the Supreme Court, including quantification of disposal timelines, types of adjournments, and reasons for delays. Key findings indicate persistent systemic delays well beyond the statutory six-month period, frequent adjournments on insubstantial grounds, inefficient witness examination, and non-uniform procedures, all of which undermine the objective of timely justice; the article recommends enforceable statutory timelines and greater institutional discipline as crucial reforms to restore faith and effectiveness in electoral adjudication.

Review of Facts by the Supreme Court in Election Cases: A Tale of Two Norms (JILI (1976))

The adjudication of election disputes by the Supreme Court of India stands at the intersection of legal scrutiny and democratic integrity. Central to this judicial role is the delicate balance between respecting lower court judgments and ensuring electoral fairness in cases fraught with allegations of corrupt practices. The article "Review of Facts by the Supreme Court in Election Cases: A Tale of Two Norms[44]" examines this dual normative framework guiding the Supreme Court's approach to reviewing factual findings in election disputes. This examination is crucial as it navigates the court's adherence to legal finality while addressing the profound implications of electoral malpractice allegations on democratic processes. While the Court typically upholds trial court judgments to ensure judicial continuity and efficiency, the article underscores the complexity of election cases, particularly those alleging corrupt practices. These cases, involving allegations that strike at the heart of democratic processes, demand a nuanced and vigilant approach from the judiciary. In ordinary circumstances, the Supreme Court refrains from re-evaluating factual findings made by lower courts unless there are glaring errors or procedural irregularities. This practice aims to maintain respect for trial courts' expertise in assessing witness credibility and evaluating evidence, thus promoting legal finality and judicial economy. However, when election disputes arise, especially those involving accusations of bribery, undue influence, or electoral malpractice, the stakes are high. The integrity of the electoral process and public trust in democratic institutions are directly impacted. In such contentious cases, the Supreme Court must balance the imperative of respecting trial court judgments with the duty to ensure electoral fairness and uphold the rule of law. This dualistic approach involves carefully scrutinizing whether the lower court's findings were based on a thorough and unbiased assessment of evidence. If there are substantial grounds to suspect a miscarriage of justice or a failure to consider crucial evidence, the Supreme Court intervenes to safeguard the electoral process's integrity. By adopting this balanced approach, the Supreme Court aims to reinforce public confidence in the judiciary's ability to adjudicate election disputes fairly and impartially. It acknowledges the gravity of electoral allegations and the need for thorough scrutiny while also recognizing the practical constraints and expertise of trial courts. This nuanced jurisprudence strikes a delicate balance between judicial restraint and judicial oversight, ensuring both legal certainty and electoral probity in the democratic framework.

Challenges and Way Ahead

- When an election petition is not concluded within the specified six-month period and is dismissed after the office's tenure is completed, it raises serious concerns. Delays render petitions pointless, leaving potential wrongdoing unaddressed and the elected individual unaccountable. This undermines the electoral process, erodes public trust, and highlights the need for timely resolution mechanisms. N. L. Rajah, in his article “Don’t dismiss those election petitions,[45]” argues that instead of dismissing petitions as infructuous, the judiciary should take these cases to their logical end. He discusses the issue of election petitions often remaining unresolved beyond the term of office. The Representation of the People Act, 1951, mandates resolution within six months, but delays are common. Following the 2009 Lok Sabha elections, none of the 110 filed petitions were resolved within the stipulated time, and 25 were still pending after the five-year term. These delays lead to dismissals as infructuous, treating issues as no longer relevant. The author cites the Supreme Court's ruling in Sheodhan Singh vs. Mohan Gautam, which emphasized that election disputes are public concerns, not just private grievances. The Court highlighted that election petitions contest the integrity of the electoral process. Even if the petitioner loses interest, the court can continue proceedings with other parties. The author asserts that the judiciary should resolve these petitions to maintain electoral integrity, serving the public interest and preserving democratic processes.

- While High Courts are designated as the authority to hear election petitions, their powers are circumscribed by the specific provisions of the Representation of the People Act and the Constitution. The article[46] by S. Rahul and P.B.V. Nageswara Rao delves into the precise jurisdictional boundaries of High Courts in adjudicating election disputes under Article 329(b) of the Constitution and Section 80-A of the Representation of the People Act, 1951. It argues that while High Courts are designated as the authorities for hearing election petitions, their powers are strictly defined by legislative provisions rather than inherent judicial authority. The authors assert that the framework established by the RP Act, and Supreme Court rulings like N.P. Ponnuswami v. Returning Officer, create a self-contained system for resolving election disputes. This system restricts High Courts from assuming rule-making powers beyond those expressly granted by statute. They emphasize that any rule-making by High Courts must derive from explicit legislative authorization, as seen in cases like Nawab Khan v. Vishwanath Shastri, where the court allowed High Courts to frame rules only when statutory provisions were silent. The authors caution against interpreting the designation of High Courts under Section 80-A as conferring blanket judicial or administrative powers, stressing that their role in election disputes is narrowly defined by the Representation of the People Act and constitutional provisions. They examined the implications of High Courts' jurisdiction to handle contempt matters during election petition trials, as established in T. Deen Dayal v. High Court of A.P. This precedent, while recognizing contempt powers, underscores the need for High Courts to exercise restraint within the confines of their designated roles under electoral laws. Conclusively, the article advocates for a strict adherence to statutory mandates and constitutional limitations in defining the High Courts' authority and jurisdiction in election dispute resolution.

References

- ↑ https://www.eci.gov.in/election-laws

- ↑ ADR, FAQ on Election Petitionhttps://adrindia.org/sites/default/files/FAQ%20on%20What%20is%20an%20election%20petition_English.pdf

- ↑ Section 80A of The Representation of the People Act, 1951

- ↑ Section 81 of The Representation of the People Act, 1951

- ↑ Section 82 of The Representation of the People Act, 1951

- ↑ Section 83 The Representation of the People Act, 1951

- ↑ Section 84 The Representation of the People Act, 1951

- ↑ Section 86(1) of the The Representation of the People Act, 1951

- ↑ Section 86(2) of the The Representation of the People Act, 1951

- ↑ Section 86(3) of the The Representation of the People Act, 1951

- ↑ Section 86(4) of the The Representation of the People Act, 1951

- ↑ Section 86(5) of the The Representation of the People Act, 1951

- ↑ Section 86(6) of the The Representation of the People Act, 1951

- ↑ Section 86(7) of the The Representation of the People Act, 1951

- ↑ Section 87 of the The Representation of the People Act, 1951

- ↑ Section 93 of the The Representation of the People Act, 1951

- ↑ Section 94 of the The Representation of the People Act, 1951

- ↑ Section 95 of the The Representation of the People Act, 1951

- ↑ Section 96 of the The Representation of the People Act, 1951

- ↑ Section 97 of the The Representation of the People Act, 1951

- ↑ Section 98 of the The Representation of the People Act, 1951

- ↑ Section 99 of the The Representation of the People Act, 1951

- ↑ Section 101 of the The Representation of the People Act, 1951

- ↑ Section 102 of the The Representation of the People Act, 1951

- ↑ Section 103 of the The Representation of the People Act, 1951

- ↑ Section 109-111 of the The Representation of the People Act, 1951

- ↑ sections 112 and 116 of the The Representation of the People Act, 1951

- ↑ Section 117 and 118 of the The Representation of the People Act, 1951

- ↑ Section 119, 121, and 122 of the The Representation of the People Act, 1951

- ↑ (1952) 1 SCC 94

- ↑ https://ceojk.nic.in/pdf/LandmarkJudgementsVOLI.pdf

- ↑ 2023 SCC OnLine SC 679

- ↑ (1999) 4 SCC 526

- ↑ Para 4.12. Chapter IV Election Process and Political Parties (NCRCW Report) available at https://legalaffairs.gov.in/volume-1

- ↑ Para 2.1.6.3; Ethics in Governance; Fourth Report; Ethics in Governance (availabe at: https://darpg.gov.in/sites/default/files/ethics4.pdf )

- ↑ “Ethics in Governance.” Second Administrative Reforms Commission, January 2007 https://darpg.gov.in/sites/default/files/ethics4.pdf

- ↑ Law Commission of India, Electoral Reforms, Report No.255 (March 2015) https://cdnbbsr.s3waas.gov.in/s3ca0daec69b5adc880fb464895726dbdf/uploads/2022/08/2022081635.pdf

- ↑ ADR/NEW Recommendations for Electoral Reforms, April 2011 https://adrindia.org/sites/default/files/ADR_and_NEWs_recommendations_for_electoral_and_political_reforms_Final_April_20_2011.pdf

- ↑ “Stanford-MIT Healthy Elections Project.” Web.mit.edu, 10 Mar. 2021, web.mit.edu/healthyelections/www/final-reports/recounts-election-contests.html.

- ↑ Correll, Gary Robert. "Elections--Election Contests in North Carolina" North Carolina Law Review, vol. 55, no. 6, September 1977, pp. 1245-1246. HeinOnline https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/nclr55&div=67&id=&page=

- ↑ Douglas, Joshua A. "Procedural Fairness in Election Contests." Indiana Law Journal, vol. 88, no. 1, Winter 2013, pp. 1-82. HeinOnline. https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/indana88&div=4&id=&page=

- ↑ Morris, C. and Wilks-Heeg, S. (2019). ‘Reports of My Death Have Been Greatly Exaggerated’: The Continuing Role and Relevance of Election Petitions in Challenging Election Results in the UK. Election Law Journal: Rules, Politics, and Policy, 18(1), pp.31–46. doi:https://doi.org/10.1089/elj.2018.0510.

- ↑ Ritwika Sharma and Titiksha Mohanty, ‘Adjudication of Election Petitions: How have courts fared’ in Shruti Vidyasagar, Shruthi Naik and Harish Narasappa (eds), Justice Frustrated: The Systemic Impact of Delays in Indian Courts (Bloomsbury India 2020) 119-131; available at: https://dakshindia.org/Justice-Frustrated/section-three-2.xhtml

- ↑ Joseph Minattur, ‘Review of Facts by the Supreme Court in Election Cases: A Tale of Two Norms’, 17 JILI (1975) 76. Available at: http://14.139.60.116:8080/jspui/handle/123456789/16405

- ↑ Rajah, N.L. (2014). Don’t dismiss those election petitions. The Hindu. [online] 18 May. Available at: https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/op-ed/Don%E2%80%99t-dismiss-those-election-petitions/article11640697.ece

- ↑ Rahul, S. and Rao, P.B.V.N. (n.d.). Eastern Book Company - Practical Lawyer. [online] ebc-india.com. Available at: https://ebc-india.com/lawyer/articles/2001v8a2.htm