Environment Impact Assessment

What is Environment Impact Assessment

Environmental Impact Assessment (“EIA”), broadly, is an effort to “anticipate, measure and weigh the socio-economic and biophysical changes that may result from a proposed project.[1] The concept is based on the idea that the possible environmental impacts of a project should be evaluated before it receives approval. Beyond informing authorities about the environmental consequences of a proposal and its possible alternatives, the EIA process also ensures that those who may be affected have a chance to be heard. It can recommend ways to reduce environmental damage or propose less harmful options. Essentially, EIA aims to predict and understand the potential negative effects of major developments, justify them in social and ecological terms, and design measures to reduce or prevent harm.

EIA systematically examines both beneficial and adverse consequences of the project and ensures that these effects are taken into account during project design. It helps to identify possible environmental effects of the proposed project, proposes measures to mitigate adverse effects and predicts whether there will be significant adverse environmental effects, even after the mitigation is implemented. By considering the environmental effects of the project and their mitigation early in the project planning cycle, environmental assessment has many benefits, such as protection of environment, optimum utilisation of resources and saving of time and cost of the project.[2]

According to the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC), “Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) is an important managerial tool adopted for proactively managing development projects which seeks to assess the potential impacts of a project on the environment”. In the same manner, EIA incorporates environmental consideration into development planning and, thus, contributes to the achievement of sustainable development.

A beginning in this direction was made in our country with the impact assessment of river valley projects in 1978-79 and the scope has subsequently been enhanced to cover other developmental sectors such as industries, thermal power projects, mining schemes etc. To facilitate collection of environmental data and preparation of management plans, guidelines have been evolved and circulated to the concerned Central and State Government Departments. EIA has now been made mandatory under the Environmental Protection Act, 1986 for 29 categories of developmental activities involving investments of Rs. 50 crores and above.

Official Definition of Environment Impact Assessment

Legal provisions relating to Environment Impact Assessment

As defined in the Environmental Protection Act, 1986

On 27 January 1994, the Union Ministry of Environment and Forests (MEF), Government of India, under Section 6 of the Environmental (Protection) Act 1986, which grants the Central Government the power to make rules to regulate environmental pollution. These rules can cover various aspects, such as setting standards for air, water, and soil quality, defining maximum allowable limits for pollutants, and establishing procedures for handling hazardous substances. Under this, it promulgated an EIA notification making Environmental Clearance (EC) mandatory for expansion or modernisation of any activity or for setting up new projects listed in Schedule 1 of the notification. Since then there have been 12 amendments made in the EIA notification of 1994.

As defined in the EIA Notification, 2006

According to the EIA Notification, 2006: - “Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) is the overall process of identifying, predicting, evaluating and communicating the biophysical effects of proposed activities on the natural environment”. The EIA process identifies whether a project calls for more detailed environmental assessment before it is given the green light. The purpose of an EIA is to make sure that any environmental effects that might come with a proposed project, are considered from the start.

The EIA Notification of 2006 updated and expanded upon previous regulations:

Mandatory Requirement: EIA has now become compulsory for more than 30 types of projects the investment proposal of which is to be more than ₹50 crores.

Categorization of Projects: Projects are subdivided into Category A (Projects where the DPR prepares a national-level appraisal) and Category B (Projects where no more than state level appraisal is prepared). Category A projects are appraised through Impact Assessment Agency (IAA) and the Expert Appraisal Committee (EAC) while Category B projects are appraised by the State Level Environment Impact Assessment Authorities (SEIAA) and the State Level Expert Appraisal Committees (SEAC).

Process Stages: Principal activities of EIA include the screening, scoping, public hearing, and appraisal stages.

As defined in the EIA Notification, 2020

In March 2020, the MoEF&CC inserted Appendix IX into the EIA Notification, exempting several types of activities from prior environmental clearance. Among them was Item 6, which allowed the extraction or borrowing of ordinary earth for linear projects, now defined under Appendix-XIV as projects of slurry pipelines, oil and gas transportation pipeline, highways or laying of railway lines, which require extraction or sourcing or borrowing of ordinary earth above the threshold of 20,000 cubic metre and does not require prior environment clearance under this notification

The rationale behind this exemption was ostensibly to ease procedural delays and facilitate swift infrastructure development. However, the language used in the exemption was vague, “linear projects” was not defined and no thresholds or conditions were placed on the volume or method of earth extraction. It made no distinction between ecologically sensitive areas and degraded lands, nor did it outline whether excavation near wetlands, forests, or water bodies required separate clearance. These gaps have resulted in misuse, as developers have exploited the exemption to circumvent clearance processes, even in areas where significant ecological disruption has occurred.

The March 2025 amendment to the EIA Notification, 2006, introduces a layer of procedural discipline that many developers had grown unaccustomed to since 2020, when the exemption was introduced. Excavation for ordinary earth, once a routine and often unregulated aspect of project execution, must now conform to a defined legal framework with clear environmental safeguards. As a result, developers must reassess project timelines, permitting strategies, and even financial allocations to accommodate these newly formalised requirements.

As defined in official reports

As defined in the Annual Report of the Ministry of Environment, Forest, and Climate Change

The Annual Report of 2024-25 defines Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) as a planning tool designed to integrate environmental considerations into development from the earliest stages. Introduced in India in 1978 for river valley projects, it became formally regulated through the EIA Notification, 1994, which mandated clearance for 29 (later 32) categories of projects. A major reform came with the EIA Notification, 2006, which created a more transparent, efficient, and decentralized system, expanded mandatory clearance to 39 project categories, and shifted the basis of regulation from investment size to environmental impact potential. Public participation and early-stage safeguards also became central features.

Both the EIA Notification, 2006 and CRZ Notification, 2011 have been periodically amended to streamline clearances. Environmental safeguards such as air and water quality protection, biodiversity conservation, greenbelt development, and wildlife management are imposed on all approved projects to minimize ecological harm during construction and operation.

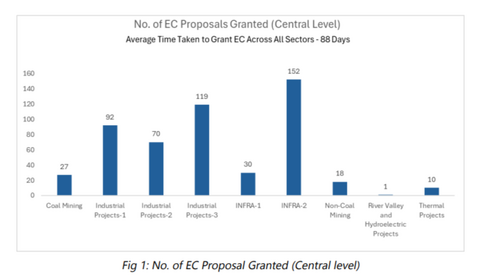

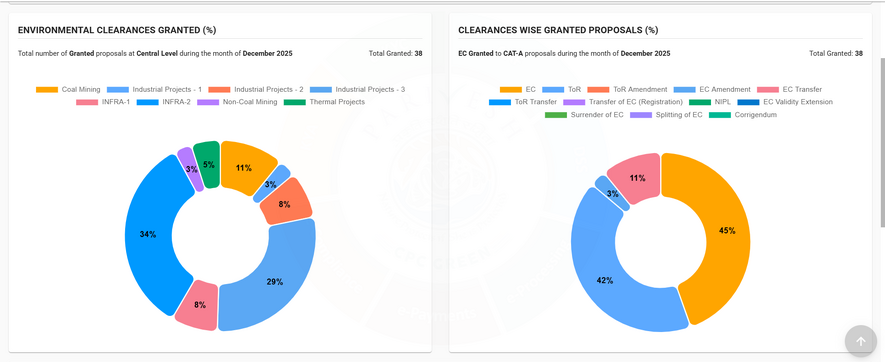

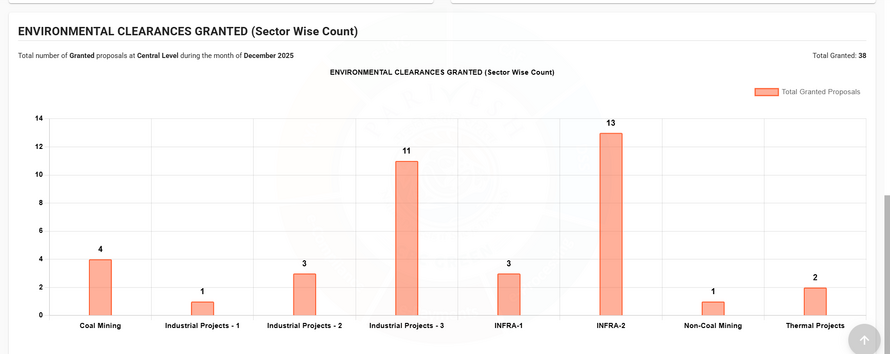

In 2024, various sectoral Expert Appraisal Committees (EACs) reviewed Category “A” projects across industries including thermal power, mining, river valley, hydroelectric, infrastructure, nuclear, and defence. Committees also conducted site visits when necessary. A total of 519 projects received Environmental Clearance (EC) between 1 January and 31 December 2024, with an average processing time of 88 working days, well within the allotted 105 days.

To support decentralized environmental governance, the Ministry has established 34 State/UT-level Environment Impact Assessment Authorities (SEIAAs) under the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986. These bodies are responsible for granting ECs to Category “B” projects appraised by the corresponding State Expert Appraisal Committees (SEACs).

As defined in the Forest (Conservation) Amendment Bill, 2023 Report

i) Scope of Applicability: EIA regulations apply to land which was officially classified as forest and registered in government records following October 25 1980. The exclusion applies to areas that transitioned to non-forest utilization by December 12, 19967.

ii) Exemptions: Some projects hold exception status which allows for less stringent EIA requirements. The bill permits strategic linear projects constructed near border areas along with security infrastructure and selected roadside developments and public utility installations. These projects hold exemptions which require compensatory afforestation as one possible condition.

iii) Non-Forest Activities: Under this bill the term "non-forest purpose" now covers additional forest-related conservation activities and management programs which leads to efficient project processing while needing simplified EIA assessments.8

iv) Survey Activities: When considering survey activities the Central Government has authority to establish conditions that determine their status regarding "non-forest purposes" and how it affects the EIA review process.

v) Centralized Oversight: Through the Act's provisions the Central Government received authority to direct implementation practices toward unified EIA procedures.

As defined in the National Green Tribunal report

According to this report EIA is the decision making tool that identifies the environment , economic and social impact of the project before its approval. The project involves mining of Building Stone, Khandas & Gitti, Boulder over an area of 2.0 hectares with a production capacity of 20,000 m³ per year.

Environmental Impacts and Mitigation Measures: Regular water sprinkling and plantation activities along roads to reduce dust. Mining will not go beyond the groundwater depth to avoid contamination. Use of well-maintained vehicles and machinery to reduce noise levels. Proper management of topsoil and overburden to prevent erosion.

Important Environmental Impact Assessment Notifications and Amendments

Notification dated 01.12.2009 – Overhaul of Construction & Township Projects

This amendment substantially revised the regulatory thresholds for Building & Construction and Township & Area Development projects, which had earlier been ambiguously defined. It introduced clearer criteria based on built-up area and land area, separating large construction projects into Category A (requiring appraisal at the Central level) and Category B (requiring SEIAA appraisal). The amendment improved predictability for urban development by specifying when public consultation was needed and when it could be exempted. Overall, it shifted India’s construction sector from an investment-based to an impact-based regulatory model.

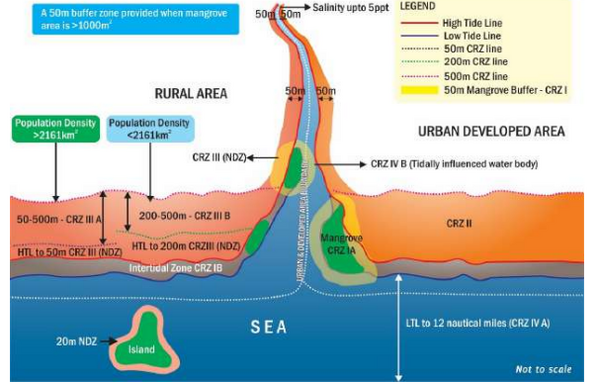

Notification dated 04.04.2011 – Alignment with the CRZ Notification, 2011

After the Coastal Regulation Zone (CRZ) Notification, 2011 came into force, this amendment harmonised EIA requirements for activities taking place in coastal and ecologically sensitive shorefront areas. It clarified that certain activities such as construction in CRZ-II, port and harbour expansion, and tourism infrastructure would require prior EC under the EIA Notification in addition to CRZ clearance. By aligning both frameworks, it ensured that development along India’s coastline adhered to uniform environmental safeguards and avoided conflicts between the two regulatory regimes.

Notification dated 13.12.2012 – Tightening of General Conditions (GC)

This amendment strengthened the “General Condition,” which triggers mandatory appraisal by the Centre (Category A) for projects located within 10 km of protected forests, wildlife sanctuaries, national parks, critically polluted areas, eco-sensitive zones, or interstate boundaries. It made district authorities responsible for verifying distances and removed discretionary loopholes. As many projects automatically got upgraded from Category B to Category A, this became one of the most impactful changes in ensuring that ecologically sensitive locations received higher scrutiny and stricter environmental safeguards.

Notification dated 22.08.2013 – Scoping & Terms of Reference (ToR)

It also implements recommendations of a High-Level Committee constituted in 2012 to review EC requirements for highways, buildings, and SEZ projects. Specifically, it exempts certain highway expansion projects from the scoping stage, allowing their EIA and Environment Management Plan (EMP) to be prepared based on model Terms of Reference (ToR) provided by the Ministry. Projects now requiring full appraisal are limited to National Highway expansions exceeding 100 km or involving additional land acquisition beyond 40 meters on existing alignments and 60 meters on realignments or bypasses. The amendment clarifies that smaller highway expansions, state highways (except in ecologically sensitive or hilly areas), and construction/township projects under Category B will be appraised on the basis of Form 1/Form 1A or conceptual plans, streamlining EC procedures and reducing delays for routine highway works.

Notification dated 14.08.2018 – Expansion of Public Hearing Exemptions

This amendment carved out several categories of projects that no longer required a public hearing. These included projects involving expansion of existing capacity by less than 50% without an increase in pollution load, certain pipeline and highway projects, and some offshore/onshore oil and gas exploration activities. The rationale was to speed up approval processes for low-impact or strategic infrastructure, but critics argued that it weakened public participation which is a core feature of the 2006 notification.

Notification dated 16.01.2020 – Increase in Validity of Environmental Clearance (EC)

This amendment extended the validity periods of Environmental Clearances across various sectors to better reflect project life cycles. Validity for mining projects was increased to 50 years, for river valley projects to 13 years, and for most other projects to 10 years. This reduced the frequency of renewal applications and brought stability for long-term projects such as mining and hydropower. The change was justified on the basis that many delays in project commissioning were beyond the proponent’s control, and frequent renewals created unnecessary administrative burdens.

It provides exemptions from prior environmental clearance for certain changes in production or product mix. Specifically, it allows sugar mills, distilleries, and synthetic organic chemical units to increase ethanol production or modify raw material/product mix without obtaining fresh EC, provided there is no increase in total pollution load and the production increase does not exceed 50% of the previously approved capacity. Project proponents must obtain a “No Increase in Pollution Load” certificate from the relevant State or UT Pollution Control Board. This amendment also extends similar exemptions for onshore and offshore oil and gas exploration drilling, simplifying compliance for incidental production or process changes while maintaining environmental safeguards.

Notification dated 17.02.2020 – Streamlining the Scoping Stage

This streamlines the scoping stage by introducing sector-specific Standard Terms of Reference (ToR) and enabling online issuance of ToR for certain projects. Under the amendment, Category B2 projects do not require scoping, while projects such as highway projects in border states, those in approved industrial estates, and expansion proposals of existing projects can receive Standard ToR automatically within seven working days without referral to the EAC or SEAC. Other projects are to be referred to the relevant appraisal committees within 30 days, after which the Standard ToR is issued if no action is taken. The committees may recommend additional project-specific ToR, and the validity of issued ToR is four years for most projects and five years for river valley and hydroelectric projects. This amendment aims to expedite the EC process, reduce delays, and ensure uniformity across project proposals while maintaining environmental oversight.

Notification dated 18.01.2021 – Framework for Violation / Post-Facto Environmental Clearance Cases

This amendment to the EIA Notification, 2006 was issued due to disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and nationwide lockdowns, which hindered the implementation of projects and delayed compliance with statutory timelines. Recognising widespread requests from project proponents, the Central Government temporarily excluded the period from 1 April 2020 to 31 March 2021 from the calculation of validity for both Terms of Reference (ToR) and Prior Environmental Clearances (ECs). This means that the “lost time” during COVID lockdowns would not reduce or exhaust the validity period granted under the EIA framework. Importantly, any project-related activities carried out during this period would still be treated as valid. The amendment was issued under Section 3 of the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986, and the requirement of prior public notice was waived in public interest.

Technological Transformation & Initiatives

Official Database for Environmental Impact Assessment

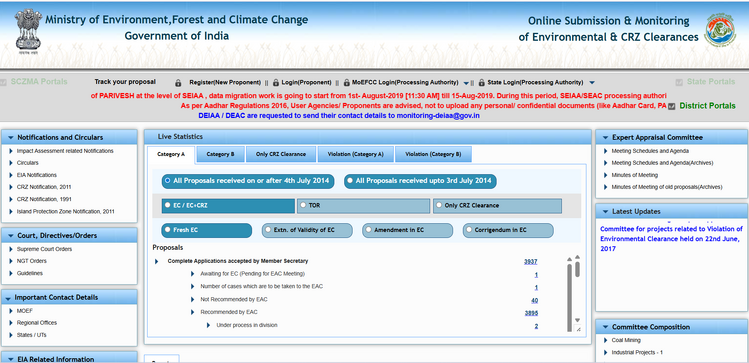

- The portal is the official online platform for submission and monitoring of environmental clearances and CRZ (Coastal Regulation Zone) clearances for projects across India.

- It is part of the government’s e-Governance efforts to make environmental clearance procedures transparent, streamlined, and accessible digitally, replacing or supplementing offline/manual processes.

- The portal helps standardize and digitise the environmental clearance process across India, increasing efficiency and reducing delays. By making clearance data, notifications, and status accessible publicly, it strengthens transparency and accountability of environmental governance. It supports better implementation of legal and regulatory safeguards for environmental protection, by integrating EIA/CRZ procedures into a unified, accessible platform.

Coastal Regulation Zone (CRZ) Framework

The Coastal Regulation Zone (CRZ) framework was first introduced in 1991 to protect coastal ecosystems while ensuring livelihood security for fishing and coastal communities. It set out rules on categorisation of coastal areas, activities permitted or prohibited within them, and the preparation of Coastal Zone Management Plans (CZMPs). After multiple amendments and evolving concerns from coastal states and stakeholders, the CRZ Notification, 2011 replaced the 1991 norms to provide a more updated regulatory structure.

Growing demands for further reform led to the constitution of the Shailesh Nayak Committee in 2014, which undertook extensive consultations and submitted recommendations in 2015. Based on these recommendations and public feedback on a 2018 draft, the Union Cabinet approved the CRZ Notification, 2019, issued in January 2019. The new notification aims to balance conservation with economic development, improve the quality of life of coastal communities, and promote sustainable use of coastal resources.

The 2019 notification becomes fully operational only after each coastal state updates its CZMP in alignment with the new norms. The Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC) issued guidelines for this transition, and CZMPs of Odisha, Karnataka, Maharashtra, and Kerala have been approved. For island territories, the earlier IPZ Notification, 2011 has similarly been superseded by the Island Coastal Regulation Zone (ICRZ) Notification, 2019, with updated plans approved for Great Nicobar and Little Andaman.

Recent progress includes the reconstitution of Coastal Zone Management Authorities for Tamil Nadu and Lakshadweep, and ongoing work for Andhra Pradesh. Kerala’s CZMP under the 2019 framework has also received approval. In 2024, the National Coastal Zone Management Authority convened to address key management issues, and the Ministry granted 61 CRZ clearances for various developmental projects, ensuring adherence to conservation safeguards under the regulatory framework.

IPZ (Island Protection Zone) Notification, 2011

- The IPZ Notification, 2011 was issued to provide a regulatory and management regime specific to islands — especially the islands of Andaman & Nicobar Islands and Lakshadweep Islands, recognizing that their ecology, social structure, and vulnerability to natural hazards differ significantly from mainland coastal areas.

- The objectives include: ensuring livelihood security for local communities (such as fisherfolk and tribal populations), conserving and protecting island ecosystems, and facilitating sustainable, scientifically-informed development that accounts for hazards like sea-level rise, erosion, tsunamis, etc.

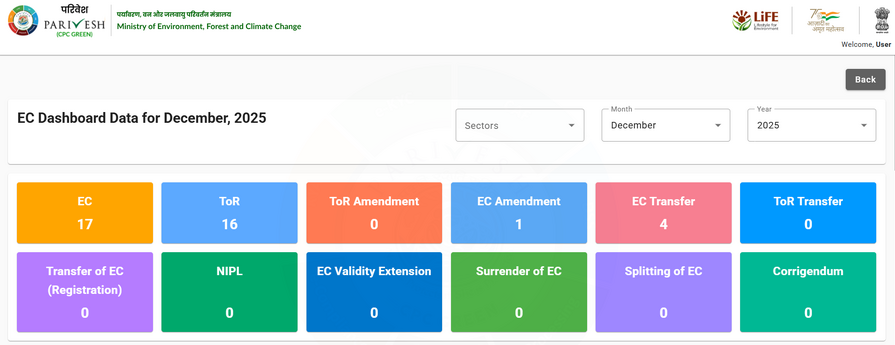

PARIVESH 2.0

It was launched in 2018 as a single-window platform for Environment, Forest, Wildlife, and Coastal Regulation Zone (CRZ) clearances, PARIVESH (Pro-Active and Responsive facilitation by Interactive, Virtuous and Environmental Single-window Hub) aimed to improve e-governance and ease of doing business. By 2019, it was operational across all States/UTs, Regional Offices, and MoEFCC. The upgraded PARIVESH 2.0 integrates modern technologies such as GIS, data analytics, and automation to enhance decision-making, transparency, and efficiency in granting and monitoring environmental clearances. Key modules include:

- Know Your Approval (KYA): Helps project proponents assess environmental sensitivity for better planning and reduced costs.

- Decision Support System (DSS): GIS-enabled tool aiding in informed decision-making for environmental clearances.

- End-to-End Online Processing: Ensures paperless clearance management, transparency, accountability, and reduced carbon footprint.

In 2024, PARIVESH 2.0 marked a major step forward in India’s digital environmental governance by enhancing efficiency, transparency, and sustainability in the clearance process. The upgraded system introduced end-to-end online processing for faster decision-making, reducing the average time for granting Environmental Clearances to about 88 days. It also enabled online submission of compliance reports, extended the processing of Category B projects to state authorities, and strengthened post-clearance monitoring through a dedicated Compliance and Monitoring Division. New modules such as the Accredited Compensatory Afforestation system, CAMPA Digital APO, and improved CRZ clearance workflows streamlined environmental management and resource planning. Together, these reforms reflect the Ministry’s commitment to digital transformation, sustainable development, and effective implementation of the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986.

Compliance & Monitoring Division (C&MD): It was established in July 2023 to strengthen post-clearance monitoring under the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986. It ensures adherence to clearance conditions, audits SEIAA (State Environment Impact Assessment Authority)/CZMA functioning, and takes corrective actions in case of non-compliance through show-cause notices and legal directives.

Accreditation of EIA Consultants: Only consultants accredited with QCI/NABET can prepare EIA/EMP reports. As of December 2024, there are 224 accredited EIA consultant organizations ensuring quality and reliability in environmental appraisals.

Policy Reforms:

- Standalone pellet plants categorized under item 2(c) and delegated to SEIAA.

- Low-pollution metallurgical processes delegated to SEIAA.

- Standalone rolling mills (except pickling and melting) exempted from clearance requirements.

Process of conducting Environment Impact Assessment

Stages and Application

1. Screening

This initial stage determines whether a proposed project or activity falls within the categories listed under the notification and whether a full EIA report is required. Projects are divided into Category A (central-level appraisal) and Category B (state-level appraisal). Category A projects automatically require clearance and the full EIA process, while Category B projects are further divided into B1 (which requires an EIA report) and B2 (which does not require a full EIA) based on size, location, and potential impact. This screening step thus filters out projects with lower environmental risk from going through the full EIA cycle.

2. Scoping

Once screening has established that a detailed assessment is needed, the next stage is scoping. At this stage, the relevant appraisal committee (the Expert Appraisal Committee (EAC) at central level for Category A, or the State Level Expert Appraisal Committee (SEAC) for Category B1) sets the Terms of Reference (ToR) for the EIA study. The ToR define which environmental issues must be evaluated (such as air quality, water resources, biodiversity, social impacts), what baseline data must be collected, what methodologies should be used, and what mitigation or alternatives must be considered. The ToR are issued within 60 days of the application for most cases; if they are not issued, the proponent’s proposed ToR are deemed approved.

Process for Determining Terms of Reference (TOR):

The EAC or SEAC will determine the TOR based on:

The prescribed application Form 1/Form 1A provides information needed for the assessment together with the terms of reference proposed by the applicant. A subgroup of EAC or SEAC members conducts site visits if necessary. An additional Terms of Reference (TOR) submitted by the applicant serves as the basis. Any additional information available with the EAC or SEAC.

3. Public Consultation

After the draft EIA report (covering baseline data, impact prediction, mitigation measures, alternatives, etc.) is prepared, the next key stage involves public consultation. This consists of two components: a public hearing at or near the project site (for most Category A and B1 projects), and written responses from other stakeholders who might be affected. The purpose is to enable local communities and other interested parties to express their concerns, and for those concerns to be addressed in the final EIA report. The public consultation aims to increase transparency, ensure socially inclusive decision-making, and improve the substantive quality of the assessment.

SPCB/UTPCC carries out this hearing process at or near the project site according to Appendix IV's format. The authorized body receives approved proceedings of the hearing within 45 days.

Written Responses:

The SPCB/UTPCC website together with other designated methods functions as the channel for stakeholder participation. State agencies keep secret project information protected from general access.

Special Arrangements:

In case SPCB/UTPCC does not carry out the hearing within specified time limits the regulatory authority possesses the right to choose another organization. Under challenging circumstances the regulatory authority can bypass the requirement to organize a hearing.

Post-Consultation:

All applicants need to resolve found issues following consultations before updating their Draft EIA and EMP. The regulatory authority finalizes the Revised documents that initially come from public hearings. When additional concerns arise the regulatory authority allows parties to present supplementary reports instead of updates to the Draft EIA and EMP.

4. Appraisal

At this stage a Expert Appraisal Committee or State Level Expert Appraisal Committee examines the application and the final EIA report and public hearing and consultation. This EIA process is done on even new projects, if not, on expansion or even on the modernization of a certain project. In the last formal stage, the final EIA report (incorporating public consultation outputs) is submitted to the appraisal committee (EAC or SEAC) along with the project application. The committee reviews the findings, examines whether the assessment is sufficiently robust, whether mitigation measures are adequate, and whether the alternatives have been considered. On the basis of this appraisal it recommends to the regulatory authority that the environmental clearance be granted, granted with conditions, or refused. The regulatory authority then issues the Environmental Clearance (EC) which sets out conditions the project must comply with.

Steps of the Appraisal Process:

(i) Transparent Scrutiny: EAC/SEAC evaluates applications through assessment of supporting documentation which incorporates the Final EIA report together with public consultation results. The responsible representative of the applicant can join the process to deliver explanations.

(ii) Recommendations

(iii) Approval: Grant EC with specific conditions.

(iv) Rejection: Clearly state the reasons.

Timelines:

Appraisal completion: The completion of EIA appraisal takes 60 days after obtaining the final EIA report and documentation.

Competent authority decision: 15 days post-recommendation.

Categories of Appraisal:

With EIA/Public Consultation: A detailed examination examines EIA reports together with public hearings and submitted documents.

Exempt from EIA/Public Consultation: This category requires evaluation from Form 1, Form 1A, validated data alongside site visits (when required).

Expansion or Modernization (7(ii)) applies to:

Expansion plans which entail higher production volumes or larger lease territory subscription.

Process or technology upgrades.

Changes made to product mixes that exceed pre-established limitations.

The review of Form I applications takes 60 days to analyze EIA reports together with public consultations when needed.

5. Post-Clearance Monitoring, Compliance & Follow-up

While not always explicitly framed as a separate stage in the notification, in practice the EIA regime requires that once clearance is granted, the project proponent implement the mitigation and environmental management measures (EMPs) set out in the clearance conditions. Monitoring requirements (e.g., periodic environmental reports, audits), compliance with conditions, and enforcement mechanisms ensure the EIA’s predictions and mitigation commitments are realised. Failure to comply may result in suspension or revocation of clearance.

International Experiences

United States of America

On January 1, 1970, the US government signed into law the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) with the intention of establishing a national policy for the “protection, maintenance, and enhancement of the environment” with regard to federal projects. Specifically, federal agencies were to implement consideration of the environment into their decision-making protocol by way of preparation of an environmental statement that assessed both the potential impacts of a proposed project and those of reasonable project alternatives. NEPA also established the range of topics for analysis, the agencies that were expected to provide feedback into the process and the body that would oversee this effort.

NEPA was, and continues to be, broad level guidance that affects only a subset of projects (generally those funded by federal agencies). As such, many states have taken to implementing more restrictive environmental regulations. For example, the state of California implemented the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). While retaining the general principles of NEPA, CEQA introduced a legal requirement for all public and private planning applications go through a screening process and established more detailed thresholds by which to determine impact significance.

The 1985 Directive has since been amended to: increase the type of projects that require EIA; establish screening criteria and the type of information required in EIA; and to bring the analytical standards more in line with the EU., Many of these changes have been paralleled by amendments to NEPA in the US. While still similar to NEPA, one notable difference in EU and UK EIA legislation is that there does not exist a single agency to oversee the EIA process, as well as the multiple and varied directives.

Similar to the way in which the EIA Directive was initially based on NEPA, it appears that the most recent draft of the proposed revised EIA Directive is closing in on the example set by CEQA by trying to create more practical and informative EIA documents.

This is particularly true with regard to:

- the range of projects that require screening;

- the need for project scoping and consultation, as well as established timeframes;

- the need to renew EIA requirements with ever-changing infrastructure, technology, and social pressures; and

- the quality of data considered necessary in an EIA.

At its root, EIA is as much a public information process as it is one to identify and mitigate the potential environmental impacts of development. However, it is often difficult to measure in a meaningful way if legislation has been transformed in a manner that advances both ideals evenly.[3]

People's Republic of China

It has been nearly 20 years since the Law of the People's Republic of China on Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) formally came into effect in 2003. The development of China's EIA system has gone through the stages of exploration, practice and reform. The evaluation objects have expanded from construction projects to planning, and then to policies, forming an EIA system with Chinese characteristics.

China introduced the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) system in the 1970s. In 2003, China formally promulgated the EIA Law, which established the legal status of the EIA system and, for the first time, set out clear provisions for planning EIA. Since then, China has started to build up its EIA system around project EIA and planning EIA. Unlike some European countries which included Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) in the early stage of the establishment of the EIA system, SEA in China has gone through a process of starting from scratch. Since 2003, SEA in China mainly includes planning EIA, and its concept is also proposed relative to project EIA. It was not until 2015 that policy EIA was included in the scope of SEA in China. In the 20 years since the promulgation of the EIA Law, the EIA system has effectively improved the quality of China's ecological environment by giving full play to its characteristics of preventing ecological damage and environmental pollution at the source.

China has reformed the EIA system by revising the EIA Law twice and improving the supporting technical guidelines for EIA for the betterment of both management system and technical system. By continuously consolidating and enhancing the status of the EIA system in China's environmental management system and making full use of its advantages in preventing pollution at source, China gives full play to the role of the EIA system in balancing high-quality economic development and high-standard protection of the ecological environment. [4]

European Union

The European Union implements EIA through Directive 2014/52/EU, which updated and replaced the earlier 2011 EIA Directive. This directive mandates that all major infrastructure, industrial, energy, and waste management projects undergo a thorough environmental assessment before approval. EU law emphasizes public consultation, transparency, and transboundary environmental effects, requiring member states to harmonize their national EIA procedures with EU standards. Projects likely to have significant cross-border impacts must also undergo transboundary EIA processes to consult neighbouring countries.

In 2012 the Commission adopted a proposal to amend Directive 2011/92/EU based on a thorough impact assessment. The aim was to lighten unnecessary administrative burdens, reinforce the decision-making process and make it easier to assess potential impacts without weakening existing environmental safeguards. Following amendments introduced by the European Parliament and the Council, the revised Directive entered into force on 15 May 2014. Member States had 3 years to transpose the Directive. The Commission drafted an informal checklist to help Member States when transposing the Directive. Under the EIA Directive, EU Member States must provide statistics to the Commission on how the Directive is implemented in their countries every six years. This includes the numbers of projects assessed under the two annexes of the Directive, average length of time the EIA process takes, and the costs involved.

An EIA is required for the various projects such as:

- nuclear power stations

- long-distance railways

- motorways

- express roads

- waste disposal installations for hazardous waste

- dams of a certain capacity

For other projects, including urban or industrial development projects, roads, tourism development and canalisation and flood relief works, it is up to individual EU Member States to decide if there will be an EIA on a case-by-case basis or by setting specific criteria (such as the location, size or type of project). There are also strict rules about how the public is informed of the project and the fact that it is subject to an EIA procedure and how those affected can participate in the decision-making process. The public is also informed of the decision afterwards and can then challenge before the courts.[5]

United Kingdom

The Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) system in the UK is a legal process designed to ensure that proposed developments likely to have significant environmental effects are properly assessed before planning consent is granted. Governed mainly by the Town and Country Planning (Environmental Impact Assessment) Regulations 2017, which implement the EU EIA Directive into domestic law, the process involves screening (to determine whether an EIA is required), scoping (identifying key issues to be assessed), preparing an Environmental Statement, and public consultation, after which the planning authority makes a decision informed by environmental considerations. Projects listed in Schedule 1 automatically require EIA, while Schedule 2 projects require assessment only if they meet set thresholds or are likely to significantly affect the environment, particularly in sensitive areas. The purpose of EIA is to integrate environmental protection and public participation early in planning, improve transparency, and identify mitigation measures, though critiques include inconsistent screening practices, limited influence on final decisions, and future uncertainty following Brexit.

In the UK case R (Finch) v. Surrey County Council (2024 UKSC 20), the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom held by a 3-2 majority that an environmental impact assessment (EIA) under the Town and Country Planning (Environmental Impact Assessment) Regulations 2017 must include downstream (“Scope 3”) greenhouse-gas emissions if extraction projects make combustion of the extracted fossil fuel inevitable, in that case the oil would inevitably be refined and burned, so the emissions were sufficiently causally linked and “likely” to occur, hence the planning authority’s decision to omit them was unlawful.[1]

Canada

Canada’s EIA framework is established under the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act (2012), which applies to projects that may affect federal lands or federal interests. The law emphasizes sustainable development and requires project proponents to identify potential environmental impacts, mitigation measures, and alternatives. A distinctive feature of Canada’s system is the focus on cumulative effects and the requirement for Indigenous consultation, ensuring that local communities and traditional land users are meaningfully involved in decision-making processes.

Australia

Australia regulates EIA primarily through the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act, 1999, which requires assessment of projects affecting matters of national environmental significance, such as World Heritage sites, wetlands, and endangered species. The system incorporates public participation and provides opportunities for stakeholders to comment on assessments. Each state and territory also has its own environmental assessment laws which allows for a dual-layered review system, where both federal and state approvals may be required for a project.

Other Notable Countries

Countries such as Japan, South Korea, China, Brazil, South Africa, and New Zealand have well-established EIA regimes, often modelled on international best practices. Japan and South Korea focus on industrial and urban projects, China integrates EIA into its development planning, while Brazil and South Africa incorporate strong social and biodiversity safeguards. In many developing countries, EIA is now mandatory for large infrastructure, mining, and energy projects that reflects a global trend toward integrating environmental considerations into the planning process.

What India can take away from these International Experiences

India’s EIA system can benefit greatly from enhanced public participation and transparency, lessons drawn from countries like the United States, Canada, and the EU. In these nations, communities, NGOs, and stakeholders are actively involved from the earliest stages of project planning, with public hearings, comment periods, and easy access to draft EIA reports. India could adopt similar practices by making EIA documents and monitoring reports widely accessible online, in regional languages, and by institutionalizing early-stage consultations, ensuring that environmental concerns of local populations are genuinely considered before approvals are granted.

Another area of improvement lies in strategic and cumulative impact assessment, as practiced in Canada and the EU. Instead of evaluating projects in isolation, these countries assess the combined environmental impacts of multiple projects in a region and consider ecosystem-level effects. India could implement this approach in coastal zones, industrial corridors, river basins, and mining areas, integrating EIA with broader land-use planning, urban development, and industrial zoning to prevent environmental degradation and ensure sustainable development at a landscape or regional scale.

Finally, India could strengthen post-clearance monitoring, compliance, and technology integration, drawing inspiration from Australia, China, and Canada. These countries employ GIS mapping, satellite imagery, and real-time monitoring systems to track project impacts, enforce environmental safeguards, and take corrective action when necessary. By adopting such technologies, India can move from reactive to proactive environmental management, ensuring stricter enforcement, better protection of vulnerable communities, and faster, more predictable clearance processes without compromising environmental integrity.

Research that engages with Environmental Impact Assessment

Review of Indian studies on environmental impact assessment (2025)[6]

This paper by Kritika and Anjali Sharma shows that while EIA remains the primary legal instrument for environmental clearance in India, there are consistent concerns about its effectiveness. Studies point to weak public participation, variable quality of EIA reports, and uneven compliance across sectors. The authors argue that while procedural aspects (clearance, documentation) are mostly followed, the effectiveness in terms of environmental protection and sustainable development is mixed.

The progress and prospect of environmental impact assessment system in India: from 1994 to 2020 notification by Ziaul Islam and Shuwei Wang[7]

The authors argue that though EIA was originally designed to ensure public participation and environmental protection, over time there has been a decline in participatory safeguards particularly after the 2006 and 2020 notifications. They note that decision‑making appears increasingly oriented toward facilitating development, often at environmental or social cost.

Evaluating EIA systems' effectiveness: A state of the art (2018) by John J. Loomis and Mauricio Dziedzic[8]

The authors categorise “effectiveness” into four dimensions that are procedural, substantive, transactive, and normative. They show that most research focuses on procedural effectiveness (whether required steps are followed), while substantive effectiveness (actual environmental protection, mitigation) and normative effectiveness (whether EIA aligns with broader sustainability goals) are often neglected. They argue for more multidimensional and long-term studies.

The effectiveness of environmental impact assessment systems in São Paulo and Minas Gerais States (2017) (Brazil Case Study) by Maria E Almeida and Marcelo Montano[9]

The study finds that the EIA systems in these states are relatively effective on procedural aspects (licensing, paperwork, compliance). But they perform poorly on substantive aspects like public participation, exploring locational alternatives, and assessing cumulative environmental impacts. As a result, EIA often ends up enabling only minor design adjustments or mitigation rather than influencing project decisions fundamentally.

Related terms

EIS (Environmental Impact Statement)

SEA (Strategic Environmental Assessment)

Risk (Risk Assessment)

EC (Environmental Clearance)

EMP (Environmental Management Plan

Participation (Public Participation)

Appraisal (Environmental Appraisal)

Consultant (Accredited Consultant)

Eco-sensitivity (Eco-Sensitive Areas)

References

- ↑ Shyam Divan and Armin Roseneranz, Environmental Law and Policy in India: Cases, Materials, and Statutes, 417 (Oxford University Press, India, 2001).

- ↑ Centre for Science and Environment, “Understanding EIA,” Centre for Science and Environment, accessed August 30, 2025, https://www.cseindia.org/understanding-eia-383

- ↑ The Institute of Sustainability and Environmental Professionals, “EIA in the US, the UK and Europe,” ISEP, accessed August 30, 2025, isepglobal.org/articles/eia-in-the-us-the-uk-and-europe.

- ↑ Yang, Y. “The Evolution of China’s Environmental Impact Assessment.” Environmental Impact Assessment Review 95 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2023.106843

- ↑ European Commission, “Environmental Impact Assessment,” Environment – Law and Governance – Environmental Assessments, European Commission, accessed August 30, 2025, environment.ec.europa.eu/law-and-governance/environmental-assessments/environmental-impact-assessment_en

- ↑ Kritika, Anjali Sharma, Review of Indian studies on environmental impact assessment, Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management, Volume 21, Issue 1, January 2025, Pages 117–130, https://doi.org/10.1093/inteam/vjae004

- ↑ Islam, Z., & Wang, S. (2022). The progress and prospect of environmental impact assessment system in India: from 1994 to 2020 notification. EQA - International Journal of Environmental Quality, 50(1), 20–25. https://doi.org/10.6092/issn.2281-4485/15427

- ↑ John J. Loomis, Maurício Dziedzic, Evaluating EIA systems' effectiveness: A state of the art, Environmental Impact Assessment Review, Volume 68, 2018, Pages 29-37, ISSN 0195-9255, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2017.10.005.

- ↑ https://doi.org/10.1590/1809-4422ASOC235R2V2022017