Human Rights Commission

Human Rights Commissions in India, comprising the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) and the various State Human Rights Commissions (SHRCs), are statutory bodies constituted under the Protection of Human Rights Act, 1993.[1] They do not derive their existence from the Constitution but from parliamentary legislation, which outlines their structure, powers and functions. Their establishment was intended to create independent institutions capable of monitoring, investigating and addressing violations of human rights within the country.

Under section 2(1)(d) of the Act, “human rights” refers to the rights relating to life, liberty, equality and dignity of the individual as guaranteed by the Constitution of India or embodied in the International Covenants and made enforceable by the courts in India.[2]

Together, the NHRC and SHRCs function as oversight mechanisms intended to strengthen the protection of individual rights by conducting inquiries into human rights violations, monitoring governmental compliance, advising on policy reforms, and promoting awareness of human rights norms. Their statutory nature ensures autonomy from routine executive control, while their investigative and recommendatory powers position them as key institutions within India’s broader human rights architecture.

What is NHRC?

The National Human Rights Commission is a statutory body established under the Protection of Human Rights Act,1993.[3] It was further amended in the year 2006 and 2019[4] The purpose of establishing the National Human Rights Commission was to give effect to the UN Declaration on Human Rights 1948[5] and ensure the protection of citizens from cruelty, torture, indignity, and inhuman treatment.

Such an organisation not only protects and promotes human rights but also plays an important role in guiding how people think about these issues. By creating awareness and encouraging discussion, it helps shape public opinion, which can eventually influence how the government makes and implements policies. It also works closely with NGOs, activists, and other groups to ensure that human rights remain an important part of the national agenda. In addition to helping resolve complaints and disputes, the organisation carries out trustworthy studies, surveys, and research projects on human rights. These activities help provide reliable information, support better decision-making, and strengthen efforts to safeguard people’s rights.[6]

The NHRC's main functions include raising awareness through various means, intervening in human rights violations by government officials and armed forces, and advocating for justice in delayed cases[7]. It also holds the authority to direct the court in cases of delayed justice, ensuring compensation for victims and addressing major human rights violations. Additionally, it plays a crucial role in combating violations against marginalized groups such as women, children, religious and caste minorities, people with disabilities, prisoners, refugees, and the LGBTQ+ community.

Official Definition of NHRC

A definition for the term “National Human Rights Commission” has not been codified but the NHRC's official website defines it as the “embodiment of India’s concern for the promotion and protection of human rights”[8]. The Protection of Human Rights Act defines “Human Rights” as the rights relating to life, liberty, equality and dignity of the individual guaranteed by the Constitution or embodied in the International Covenants and enforceable by courts in India[9].

The Protection of Human Rights Act of 1993 delineates the function and powers[10]. The Act serves as a crucial framework for addressing human rights violations and promoting the protection of fundamental rights. As per Section 12 of the Protection of Human Rights Act, 1993, the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) in India has significant functions and powers. It can investigate complaints related to Human Rights violations, intervene in judicial processes involving such allegations, and inspect state-controlled institutions, making recommendations based on its observations. The NHRC is authorized to scrutinize constitutional articles protecting human rights, suggest punitive measures, and examine hindrances to the enjoyment of human rights, offering recommendations for appropriate remedies, including those related to acts of terrorism.

Mandate of NHRC

The mandate of the National Human Rights Commission derives from the Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, which establishes the Commission as the apex national institution responsible for the protection and promotion of human rights in India.[11] The Act entrusts the NHRC with a broad oversight role to ensure that the rights guaranteed by the Constitution and embodied in international human rights instruments are respected by public authorities.[12]

Under the Act, the Commission’s mandate includes the supervision of human rights enforcement, monitoring of safeguards, advising governments on reforms, and providing accessible mechanisms for addressing violations.[13] It acts as a national watchdog over state agencies by examining compliance with human rights standards, reviewing legislative and administrative frameworks, identifying systemic factors that impede rights, and promoting awareness and literacy on human rights across society.[14]

The NHRC is also mandated to contribute to India’s engagement with international human rights obligations, study relevant treaties, and make recommendations for their effective domestic implementation.[15] Through these broad statutory responsibilities, the Commission functions as the central institution tasked with ensuring that human rights protections are integrated into governance, law enforcement, and public administration at the national level.

Statutory functions of NHRC

The National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) is vested with a wide range of statutory functions under the Protection of Human Rights Act, 1993. The Commission may inquire into complaints of human rights violations or abetment, either on its own motion, on a petition filed by a victim or any person on their behalf, or pursuant to a direction of a court.[16] It may also examine cases involving negligence by public servants in preventing such violations.[17] The Commission is empowered to intervene in court proceedings relating to allegations of human rights violations, subject to the court’s approval.[18]

The Commission may visit any jail or institution under State control where individuals are detained, housed, or treated, in order to study living conditions and recommend improvements to the Government.[19] It also reviews constitutional and legal safeguards for the protection of human rights and recommends measures to strengthen their implementation.[20] Additionally, the Commission examines factors such as terrorism that hinder the enjoyment of human rights and suggests appropriate remedial steps.[21]

The NHRC studies human rights treaties and other international instruments and advises on their effective implementation.[22] It undertakes and promotes research in the field of human rights,[23] and works to spread human rights awareness through education, publications, media outreach, seminars, and related means.[24] The Commission also encourages and supports non-governmental organisations and institutions engaged in the protection of human rights.[25] It may perform any additional functions it considers necessary for the promotion of human rights.[26]

Powers to inquire

The National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) possesses extensive powers while conducting inquiries under the Protection of Human Rights Act, 1993. During an inquiry, the Commission has all the powers of a civil court under the Code of Civil Procedure, including summoning and examining witnesses under oath,[27] ordering the discovery and production of documents,[28] receiving evidence on affidavits,[29] requisitioning public records from courts or government offices,[30] and issuing commissions for the examination of witnesses or documents.[31] The Commission may also exercise any other functions prescribed by law.[32]

The Commission may require any person to furnish information relevant to an inquiry, subject to lawful claims of privilege.[33] Anyone so required is deemed legally bound to provide information within the meaning of sections 176 and 177 of the Indian Penal Code.[34] The Commission, or an authorised gazetted officer, may enter any building where relevant documents may be located and may seize or copy such documents, subject to the safeguards of the Code of Criminal Procedure.[35] The Commission is deemed to be a civil court for the purposes of prosecuting certain offences committed in its presence, such as those described in sections 175, 178, 179, 180 and 228 of the Indian Penal Code, and may forward such cases to a magistrate for trial.[36] All proceedings before the Commission are treated as judicial proceedings for the purposes of sections 193, 196 and 228 of the Penal Code, and the Commission is deemed a civil court for the purposes of section 195 and Chapter XXVI of the Code of Criminal Procedure.[37]

The Commission may transfer any complaint to the relevant State Human Rights Commission if it considers such transfer necessary and if the State Commission has jurisdiction over the matter.[38] Complaints transferred in this manner are treated as if they were originally filed before the State Commission.[39]

For investigation purposes, the Commission may utilise officers or investigation agencies of the Central or State Governments with the concurrence of the concerned government.[40] Officers conducting such investigations may summon and examine persons,[41] require the production of documents,[42] and requisition public records.[43] Statements made before such officers are treated the same way as statements made before the Commission for the purposes of protections under section 15.[44] Investigation reports must be submitted to the Commission within the specified period,[45] and the Commission must satisfy itself about the correctness of the findings and may conduct further inquiry if necessary.[46]

Statements made before the Commission cannot be used against a person in civil or criminal proceedings, except in cases of prosecution for giving false evidence, provided the statement was made in response to a question that the Commission required to be answered or was relevant to the inquiry.[47]

The Commission must also provide an opportunity to be heard to any person whose conduct is being examined or whose reputation may be adversely affected by the inquiry.[48] This requirement does not apply when a witness’s credit is being impeached.[49]

Complaint and Inquiry Procedure

The National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) follows a statutory procedure for inquiring into complaints under the Protection of Human Rights Act, 1993. The Commission may call for information or a report from the Central Government, any State Government, or any subordinate authority within a specified period.[50] If no report is received within that period, the Commission may proceed with the inquiry on its own.[51] Upon receiving a report, if the Commission is satisfied that no further inquiry is needed or that appropriate action has already been taken, it may close the matter and inform the complainant.[52] Independently of this mechanism, the Commission may also initiate an inquiry on its own if the nature of the complaint requires it.[53]

During or after an inquiry, if the Commission finds that human rights have been violated, or that there has been negligence or abetment by a public servant, it may recommend that compensation or damages be paid to the victim or their family.[54] It may also recommend prosecution or other suitable action against the responsible officials,[55]along with any additional steps it considers appropriate.[56] The Commission may approach the Supreme Court or a High Court for directions, orders, or writs necessary to enforce human rights protections.[57] It may also recommend interim relief to the victim or their family during any stage of the inquiry.[58]

The inquiry report may be provided to the petitioner or their representative,[59] and must be sent to the concerned government or authority, which is required to submit comments and details of action taken within one month or within such extended time as permitted by the Commission.[60] The Commission then publishes its report, along with the comments of the government or authority and details of the action taken.[61]

For complaints alleging human rights violations by members of the armed forces, a separate procedure applies. The Commission may seek a report from the Central Government either on its own motion or upon receiving a petition.[62] After receiving the report, it may either close the matter or make recommendations to the Central Government.[63] The Central Government must inform the Commission of the action taken within three months or within such extended time as allowed.[64] The Commission is required to publish its report and recommendations along with the action taken by the Government,[65] and to provide a copy to the petitioner or their representative.[66]

The Commission must also submit an annual report to the Central and State Governments, and it may issue special reports on urgent or significant matters at any time.[67] These reports must be laid before Parliament or the relevant State Legislature along with a memorandum detailing action taken or proposed to be taken and reasons for any non-acceptance of the Commission’s recommendations.[68]

Composition of NHRC

The National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) is constituted under section 3 of the Protection of Human Rights Act, 1993. The Commission consists of a Chairperson who has been the Chief Justice of India or a Judge of the Supreme Court, one Member who is or has been a Judge of the Supreme Court, and one Member who is or has been the Chief Justice of a High Court.[69] In addition, the Commission includes three Members appointed from among persons having knowledge of, or practical experience in, matters relating to human rights, of whom at least one must be a woman.[70]

The Act also stipulates that the Chairpersons of several national commissions serve as ex officio Members of the NHRC for functions under section 12. These include the Chairpersons of the National Commission for Backward Classes, the National Commission for Minorities, the National Commission for Protection of Child Rights, the National Commission for the Scheduled Castes, the National Commission for the Scheduled Tribes, the National Commission for Women, and the Chief Commissioner for Persons with Disabilities.[71] This statutory design embeds the NHRC within a wider national human rights architecture, ensuring that concerns relating to caste, gender, children, minorities, and disability are represented at the institutional level.

The composition of NHRC includes a chairperson and 8 other members. The Chairperson of NHRC is the retired Chief Justice of India. Out of the 8 members, 4 are full-time members whereas the other 4 are deemed members.[72] Out of the 4 full-time members of NHRC:

- One member should be a working or retired Judge of the Supreme Court.

- Other member should be working or retired Chief Justice of a High Court

- Two members are selected based on their experience and knowledge of human rights.

Change in composition post 2019 Amendment

Significant reforms were made to Section 3:

- Eligibility for Chairperson: A person who has been Chief Justice of India or a Judge of the Supreme Court may now be appointed Chairperson (earlier only a former CJI).[73]

- Increase in Membership: The number of Members was increased from two to three, with a mandatory inclusion of at least one woman.[74]

- Expansion of Deemed Members: Heads of the NCBC, NCPCR, and the Chief Commissioner for Persons with Disabilities were added as deemed members, alongside the existing statutory bodies.[75]

Appointment process

The Chairperson and Members of the Commission are appointed by the President of India through a warrant under his hand and seal.[76] Appointments are made on the recommendations of a high-level selection committee consisting of the Prime Minister as Chairperson, the Speaker of the Lok Sabha, the Union Home Minister, the Leaders of the Opposition in both Houses of Parliament, and the Deputy Chairperson of the Rajya Sabha.[77] If a sitting Judge of the Supreme Court or a sitting Chief Justice of a High Court is being considered, consultation with the Chief Justice of India is mandatory.[78]

The Act also provides that appointments remain valid even if there is a vacancy in the selection committee.[79] The Chairperson and Members hold office for three years or until they attain the age of seventy years, whichever is earlier, and are eligible for reappointment.[80] They may resign by writing to the President, or may be removed only on grounds of proved misbehaviour or incapacity following an inquiry by the Supreme Court on a reference made by the President.[81]

Structure of NHRC

The NHRC is headed by a Secretary-General, an officer of the rank of Secretary to the Government of India, who functions as the Commission’s Chief Executive Officer.[82] The organisational structure consists of six divisions: the Law Division, the Investigation Division, the Administration Division, the Training Division, the Policy Research, Projects and Programmes Division (PRP&P), and the Information & Public Relations Division.[83]The Law Division receives and processes complaints, prepares case files, and supports benches of the Commission in hearings.[84]The Investigation Division is headed by a Director General of Police and comprises officers of the rank of DIG, SP, DSP and others; it conducts independent inquiries, examines reports from state agencies, and assists in cases of custodial deaths, encounter killings, and other serious violations.[85]

The Administration Division manages personnel, establishment matters, procurement, building maintenance, transport, and financial administration.[86]

The Training Division organises human rights training programmes for government officials, NGOs and civil society organisations.[87]The PRP&P Division undertakes research, coordinates thematic projects, and organises consultations and conferences.[88]The Information & Public Relations Division manages publications, media outreach, the NHRC website, and RTI facilitation.[89]

Additional functionaries

In addition to its permanent staff of around 340 personnel, the NHRC significantly extends its reach through Special Rapporteurs and Core/Expert Groups.[90]Special Rapporteurs are senior experts often retired senior civil servants or police officers appointed to monitor specific thematic areas such as bonded labour, child labour, custodial justice, disability, and refugee rights.[91]

Core Groups and Expert Groups consist of eminent individuals or representatives of specialised organisations. These groups advise the Commission on issues including health, disability, legal reforms, NGOs, right to food, emergency medical care, and unsafe medical devices.[92]Their inputs help shape the Commission’s thematic priorities and policy recommendations.

State Human Rights Commission

State Human Rights Commissions (SHRCs) are statutory bodies established under Chapter V of the Protection of Human Rights Act 1993 to safeguard and promote human rights at the state level.[93] Their creation reflects the legislative intention that human rights protection must operate at both national and sub-national tiers with parallel institutional strength.

Composition and Structure

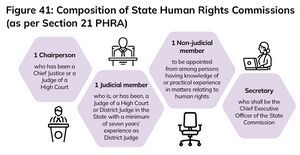

An SHRC consists of:

- A Chairperson who has been a Chief Justice or Judge of a High Court,[94]

- One Member who is or has been a High Court Judge or a District Judge with at least seven years’ experience,[95]

- One Member with knowledge or practical experience relating to human rights.[96]

Each Commission must also have a Secretary acting as the Chief Executive Officer, empowered to exercise administrative and financial functions subject to the control of the Chairperson.[97] The headquarters of every Commission is notified by the respective State Government.[98] SHRCs are empowered to inquire only into matters relatable to State List and Concurrent List subjects.[99]

Appointment Process

The appointment of the Chairperson and Members is made by the Governor based on the recommendations of a high-level committee consisting of

- The Chief Minister (Chairperson),

- The Speaker of the Legislative Assembly,

- The Home Minister,

- The Leader of the Opposition in the Legislative Assembly,[100]

- And where applicable, the Chairman and Leader of the Opposition in the Legislative Council.[101]

- Judicial members cannot be appointed without consultation with the Chief Justice of the High Court.[102]

Functions and powers

SHRCs perform the same core functions as the NHRC, applied mutatis mutandis through section 29 of the Act.[103]

Their responsibilities include:

- Inquiring into complaints of human rights violations or negligence in preventing such violations by public servants.[104]

- Visiting jails and state-run institutions to study living conditions and make recommendations.[105]

- Reviewing constitutional and statutory safeguards and proposing reforms.[106]

- Studying factors inhibiting human rights, including terrorism.[107]

- Promoting research, literacy and awareness on human rights.[108]

They hold civil-court powers when conducting inquiries,[109] may utilise state or central investigative agencies,[110] and may recommend compensation, prosecution, and interim relief.[111]

India Justice Report 2025: State Human Rights Commission

SHRCs were established to be “front line soldiers” for human rights protection with wide powers inquiring into violations, conducting jail visits, reviewing laws, and promoting human rights literacy. But the report notes that they have been chronically weakened from the outset due to lack of resources.

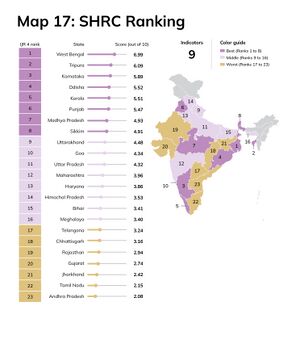

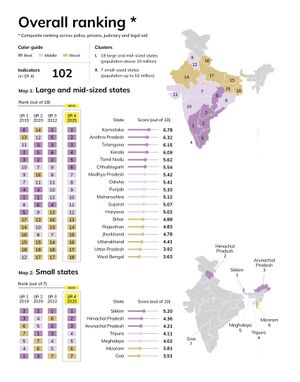

The India Justice Report 2025 presents the most detailed quantitative assessment of State Human Rights Commissions (SHRCs) to date, concluding that these bodies remain severely constrained by structural deficits in staffing, budgets, diversity, transparency, and institutional functioning.[112] Across 23 ranked states, only eight SHRCs reported less than 20 percent staff vacancy, while states such as Uttar Pradesh have had over 60 percent of all sanctioned posts vacant since 2020–21, demonstrating chronic shortages in core personnel required for inquiries and investigations.[113]

Even more concerning are the deficits in investigation wings, which are central to the Commission’s mandate. The Report records that Jharkhand, Sikkim, and Andhra Pradesh do not have separate investigation wings at all, while Goa, Gujarat, Chhattisgarh, Himachal Pradesh and Telangana report vacancy levels above 60 percent in their investigative staff.[114] These gaps critically limit the capacity of SHRCs to conduct independent inquiries, gather evidence, or follow the procedures mandated by the Act.

Leadership positions also remain highly unstable. Haryana, Jharkhand and Telangana reported having no Chairperson and no Members, rendering the Commissions non-functional for long stretches.[115] Chhattisgarh has been headed by an acting Chairperson since 2018, illustrating the long-term nature of appointment delays that weaken statutory oversight.[116]

The Report also highlights severe gender imbalance. No SHRC has ever had a woman Chairperson, and only five states reported even a single woman in their executive staff.[117] Data on women in the investigative units show similar deficits, with many commissions reporting either zero women or providing no data at all.[118]

Financial capacity remains restricted. While overall SHRC budgets increased from ₹105 crore in 2020–21 to ₹142 crore in 2022–23, utilisation remains uneven, with several states spending less than half of their allocated funds.[119] In the indicator-wise budget utilisation table, some states such as West Bengal report utilisation above 100 percent (owing to previous years’ arrears or supplemental grants), whereas others provide no budget data in response to RTIs.[120]

Case disposal data reveal patterns that raise questions about substantive performance. The IJR notes that only 4 percent of all cases before SHRCs nationwide are initiated suo motu, despite the wide scope of the Commission’s powers.[121] Meanwhile, many SHRCs record very high case clearance rates, but the Report clarifies that these stem largely from in limine dismissals summary rejections at the admission stage rather than thorough inquiries.[122] This inflates performance metrics while limiting access to meaningful remedies.

The assessment of SHRC websites reveals structural deficits in transparency and accessibility. The Report documents that six SHRCs have no functioning websites at all, while many others provide only partial or outdated data on complaints, annual reports, or hearings.[123] Several states offer websites exclusively in English or a single regional language, hampering public accessibility.[124] Furthermore, numerous SHRCs failed to disclose key information even to RTI requests filed by the IJR research team.[125]

Despite these limitations, some states showed improvements due to better disclosure and stronger administrative processes. West Bengal rose from the bottom of the rankings to first place, supported by improved staffing, increased representation of women, higher case disposal rates, and better budget utilisation.[126] However, the Report notes that even in West Bengal, more than half of the investigative wing posts remain vacant, underlining the fragility of these gains.[127]

Overall, the India Justice Report 2025 concludes that SHRCs remain “constrained by capacity deficits”, with persistent vacancies, irregular disclosures, and inadequate financial and investigative resources undermining their statutory mandate to provide human rights protection at the state level.[128] Without substantial improvement in staffing, appointments, data transparency, and autonomy, SHRCs are unlikely to function as effective frontline institutions for state-level human rights oversight.[129]

Appearance in Official Databases

National Human Rights Commission – official website

The NHRC website has a clean institutional design with a bilingual interface (English and Hindi). At the top there are accessibility tools (e.g., screen-reader toggle, text size adjustment, colour mode switch) for users with differing needs. The primary navigation menu provides links to key sections including About Us, Mandate, Composition, Organisation Structure, Strategic Plan, Annual Budget, etc. [130]

Website: Key information

Institutional Details

The site contains an About the Organisation section, describing the NHRC’s legal basis under the Protection of Human Rights Act, 1993, its mission, vision, composition, SCA accreditation, and organisational structure.[131]There are links to the Act & Rules (e.g., the 1993 Act, NHRC Procedural Regulations 1997) and to an international human rights framework (such as the UDHR, ICCPR, ICESCR).[132]

Publications and Reports

The website houses a Publications section with newsletters (Monthly, English & Hindi), annual reports, annual accounts, research project outcomes, Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) for specific issues (e.g., collection of forensic evidence in sexual assault), and the NHRC’s journal.[133]

Media, Outreach and Events

Under Media you’ll find press releases, a photo gallery, video interviews, short films, and links to webcasts of NHRC events. The Outreach section lists upcoming/ recent events, camp sittings, open hearings, core group proceedings, etc.[134]

Data and Statistics

- A live graphic / numeric dashboard on complaints: ongoing cases, new registrations, disposals during given months.[135]

- Cumulative case data for longer periods (e.g., registered cases between 2021-22 to October 2025).[136]

- Annual reports and accounts showing institutional financials, budgets, statement of activities for each year.

- Vacancy details / results of recruitment for NHRC staff.[137]

- Research and project data: lists of ongoing and completed research projects, guidelines, frameworks.[138]

HRCnet

HRCNet is an online, integrated complaint-management system developed and maintained by the National Informatics Centre (NIC) for the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) of India and the State Human Rights Commissions (SHRCs).[139] The portal was designed to streamline the handling of human rights violation complaints by providing a standardised digital interface for complainants, Commission officials and other stakeholders. It forms part of NHRC’s broader effort to modernise administrative processes, enhance accessibility and ensure greater transparency in the processing of complaints across jurisdictions.[140]

The platform enables citizens to file complaints online relating to alleged violations of rights guaranteed under the Constitution of India or international human rights covenants enforceable by Indian courts. Users may submit complaints by providing details of the incident, information regarding the victim, and supporting documents, which can be uploaded directly through the interface.[141] The lodging process incorporates OTP-based verification for mobile numbers to ensure authenticity and facilitate communication, and automatically generates a unique diary number upon successful submission. This diary number serves as the primary reference for tracking subsequent action on the complaint.[142]

HRCNet also provides facilities for users to search for complaints already filed with NHRC or SHRCs. Complaints may be searched using a variety of parameters such as diary number, case or file number, the victim’s name, date of incident or the State in which the violation allegedly occurred.[143] The platform additionally allows complainants to check the case status, which displays whether the matter is pending, disposed of, closed, or whether further action has been sought from concerned authorities.[144] Through this mechanism, complainants can monitor the progress of their cases without requiring physical visits to Commission offices.

A significant component of HRCNet is its role-based access system for Commission officials, enabling them to update case details, upload action-taken reports, issue notices, and electronically forward documents to authorities such as police departments, district magistrates and state agencies.[145] The portal facilitates internal workflow management by automating various administrative tasks, thereby reducing delays and improving accountability.

The portal hosts a statistical dashboard presenting real-time and historical data on complaints received by NHRC and SHRCs. These statistics include the number of registered complaints, those pending disposal, cases in which action has been completed, and complaints dismissed at the preliminary stage.[146] By publishing these datasets, HRCNet contributes to institutional transparency and enables researchers, journalists and policymakers to analyse trends in human rights violations and institutional response rates.

HRCNet also uploads public documents such as guidelines for lodging complaints, manuals for Commission officials, circulars and procedural instructions relevant to case management.[147] The complaint system is free to use, and complaints may be filed in any matter involving human rights violations by public servants or negligent acts of public authorities within the jurisdiction of NHRC or the respective SHRC.[148]

Through its integration of digital workflows, public access tools and structured complaint procedures, HRCNet constitutes a central element of India’s institutional framework for the protection and promotion of human rights. It strengthens accessibility for complainants across the country and enhances the efficiency of human rights commissions by reducing administrative bottlenecks, improving documentation practices and supporting coordinated action between national and state-level institutions.[149]

Research that engages with Human Rights Commission

Assessing the effectiveness of the National human rights commission, India, vis-a-vis the Paris principles relating to the status of national human rights institutions[150]

This research paper by Ruchita Kaundal and S. Shantakumar critically examines the effectiveness of India's National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) in line with the Paris Principles governing National Human Rights Institutions (NHRIs). It covers the historical context, the development of human rights law in India, and the establishment of the NHRC through the Protection of Human Rights Act 1993. The paper then conducts a detailed analysis of the NHRC's compliance with the Paris Principles, exploring aspects like representation, selection procedures, financial autonomy, and its overarching mandate. Furthermore, it highlights statutory limitations, encompassing legal and jurisdictional constraints, to provide a comprehensive assessment of the NHRC's efficacy as a national human rights institution.

The Paris principles and GANHRI

National Human Rights Institutions (NHRIs) emerged as part of a broader international effort to strengthen domestic implementation of human rights norms after the creation of the United Nations in 1945. Early debates within the UN highlighted the need for institutions that could operate at the national level to bridge the gap between international human rights obligations and domestic enforcement mechanisms.[151] In 1946, the UN Economic and Social Council formally encouraged Member States to establish local human rights committees, marking the first institutional initiative for national-level bodies dedicated to human rights protection.[152]

Substantial momentum developed in the late twentieth century. The 1978 Geneva Seminar organised by the UN Commission on Human Rights produced the first international guidelines on the structure and functioning of NHRIs, which were subsequently endorsed by both the Commission and the General Assembly.[153] The watershed moment came in 1991, when the first International Workshop on National Institutions held in Paris adopted the Principles Relating to the Status of National Institutions, now universally known as the Paris Principles. These principles established the minimum standards for independence, pluralism, mandate, powers and accountability of NHRIs, and today form the foundational benchmark for assessing institutional credibility.[154]

The global significance of NHRIs expanded further with the 1993 World Conference on Human Rights in Vienna, which expressly recognised NHRIs compliant with the Paris Principles as essential partners in the promotion and protection of human rights. The Vienna Declaration urged all States to establish and strengthen such bodies.[155] Following Vienna, the international community consolidated its institutional architecture through the creation of the International Coordinating Committee of National Institutions for the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights (now GANHRI). The ICC was tasked with accrediting NHRIs based on compliance with the Paris Principles, thereby creating a structured global system for assessing institutional independence and effectiveness.[156]

Since the 1990s, NHRIs have proliferated across all regions. According to UN OHCHR’s global survey, major waves of establishment occurred in the Americas in the early 1990s, Africa in the mid-1990s, and Asia-Pacific in the late 1990s, accompanied by steady development in Europe.[157] This expansion coincided with growing expectations that NHRIs should provide a domestic mechanism for investigating human rights violations, advising governments, monitoring detention practices, engaging with civil society, and supporting democratic governance.[158]

Academic literature underscores that NHRIs emerged as practical institutions for internalizing international human rights obligations within State systems. Scholars note that NHRIs serve as neutral, independent State bodies capable of addressing violations that fall below the threshold of international intervention, thereby enhancing domestic accountability.[159] At the same time, they operate as intermediaries between individuals, governments, and the international human rights system, enabling more effective monitoring and implementation of treaty obligations.[160]

Internationally, NHRIs now participate directly in the UN human rights system, including the Human Rights Council, Universal Periodic Review, and treaty bodies. GANHRI’s accreditation system continues to be central to ensuring that national institutions meet global standards of independence and effectiveness.[161] Together, the UN framework, the Paris Principles, and the ICC/GANHRI accreditation system form the backbone of the modern international regime governing national human rights institutions.

Needed: More Effective Human Rights Commissions in India[162]

This research paper discusses the establishment of India's National Human Rights Commission in 1993 and its evolution in response to national and international concerns about human rights violations. It highlights structural and practical limitations faced by the commissions, including the inability to enforce recommendations, composition criteria issues, time constraints, and challenges related to funding and bureaucratic functioning. The paper emphasizes the need for advocacy to bring about changes in the structure and functioning of human rights commissions for improved efficiency, with proposed reforms including enhancing their authority and addressing practical challenges. Despite the National Human Rights Commission proposing amendments, no significant action has been taken to implement reforms.[163]

International Experiences

United States of America

In the United States, there is no national human rights institution accredited under the Global Alliance of National Human Rights Institutions (GANHRI). Instead, the closest analogue is the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights (USCCR), an independent, bipartisan federal body created by the Civil Rights Act of 1957. The Act empowered the commission to investigate allegations of discrimination based on race, colour, religion, sex, age, disability, or national origin, particularly in areas such as voting rights, public education, housing, and the administration of justice.[164]

The USCCR’s statutory mandate is structured around fact-finding and advisory functions rather than enforcement authority. The commission conducts investigations, holds public hearings, issues subpoenas, compiles research reports, and submits findings and recommendations to the President and Congress. According to its mission statement, the commission “informs the development of national civil rights policy and enhances enforcement of federal civil rights laws” by providing independent, data-driven evaluations of discriminatory practices.[165]

Record-keeping preserved in the U.S. National Archives shows that from its earliest years, the commission played a notable role in shaping federal policy, its reports on voting discrimination in the American South were extensively used by Congress during the formulation of both the Civil Rights Act of 1960 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.[166] Congressional Research Service analyses likewise note that although the commission has no enforcement powers, its investigatory findings have historically influenced legislative developments concerning segregation, justice-system disparities, and civil-rights protections.[167]

The USCCR is composed of eight commissioners appointed in a bipartisan manner by the President and Congress for staggered six-year terms. The commission operates through national investigations and a network of state advisory committees that function as regional fact-finding bodies, providing localised reports on civil-rights issues. These committees contribute substantially to the commission’s nationwide data-collection capacity and offer insights into state-level disparities in civil-rights enforcement.[168]

Although the commission lacks prosecutorial or adjudicatory power, its influence stems from its independence, its authority to issue subpoenas, and its role as a fact-finding institution whose reports often shape congressional oversight, federal civil-rights enforcement priorities, and executive-branch policy initiatives.

Canada

Canada has a well-established national human rights institution in the form of the Canadian Human Rights Commission (CHRC), created under the Canadian Human Rights Act 1977. The CHRC operates as an independent federal body responsible for protecting individuals from discrimination based on race, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, age, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, marital status, family status, disability, and conviction for an offence for which a pardon has been granted.[169] Its mandate includes receiving and assessing discrimination complaints, conducting investigations, facilitating settlement, and referring cases to the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal where adjudication is required.

The CHRC also carries a proactive responsibility to promote equality and prevent discrimination. Its statutory functions include policy development, public education, compliance monitoring and issuing reports to Parliament. The commission may conduct audits of federally regulated employers to ensure compliance with the Employment Equity Act, which obliges employers to identify and remove systemic barriers to equality for women, Indigenous peoples, persons with disabilities and members of visible minorities.[170]

Although the CHRC does not make binding rulings itself, it investigates complaints and prepares cases for the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal, an independent adjudicative body empowered to issue binding decisions and remedies. The commission also represents the public interest in Tribunal proceedings, ensuring that systemic discrimination and broader equity issues are examined beyond the immediate dispute between parties.[171]

The CHRC plays an important role in shaping national equality policy. Its annual reports to Parliament analyse systemic discrimination trends in employment, housing, policing and service delivery. The commission publishes research, guidelines and policy recommendations for federal institutions and regulated industries, contributing to the broader development of human-rights standards in Canada. It also participates in Canada’s reporting obligations to international human rights bodies, including treaty-monitoring mechanisms under the United Nations system.[172]

The CHRC operates in conjunction with a network of provincial and territorial human rights commissions, each constituted under its own statutory framework. These bodies handle discrimination claims arising under provincial jurisdiction, such as housing, education, healthcare and provincially regulated employment. This multi-level system ensures comprehensive human-rights coverage across Canada’s federal structure, with the CHRC responsible for federal matters and provincial commissions addressing local issues. Despite jurisdictional separation, the commissions frequently collaborate on national human rights issues, joint statements and coordinated public policy interventions.[173]

Through its investigative powers, policy work, compliance audits and coordination with provincial and international human rights systems, the CHRC operates as one of the most developed national human rights institutions globally. Its hybrid model, combining complaint handling, public-interest advocacy, research, and systemic monitoring, positions it as a central institution in Canada’s human rights landscape.

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom’s national human rights institution is the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC), established under the Equality Act 2006. The EHRC is an independent statutory body mandated to promote and enforce equality and non-discrimination across England, Scotland and Wales, while also protecting and advancing human rights contained in the Human Rights Act 1998. It succeeded three earlier equality bodies, the Equal Opportunities Commission, the Commission for Racial Equality and the Disability Rights Commission, bringing them under a single institutional framework.[174]

The EHRC’s statutory mandate is broad. It is empowered to monitor and promote compliance with the Equality Act 2010, prevent discrimination across protected characteristics such as sex, race, disability, religion or belief, sexual orientation, age and gender reassignment, and to work towards eliminating systemic inequality in employment, education, policing and public services. The Commission also oversees the implementation of the Human Rights Act 1998, assessing whether public authorities meet standards derived from the European Convention on Human Rights.[175]

The EHRC possesses far stronger enforcement powers than many national human rights institutions. It may conduct formal investigations, issue legally enforceable compliance notices, intervene in legal proceedings, bring judicial review actions, enter into binding agreements with duty-bearers, and conduct inquiries into sectors where systemic discrimination is suspected. These powers enable the Commission to hold public and private bodies accountable and to ensure implementation of equality law through both litigation and regulatory oversight.[176]

In addition to its enforcement and investigatory functions, the EHRC plays a central role in shaping public policy. It publishes statutory Codes of Practice on equality and human rights, provides guidance to employers and public authorities, and issues reports to Parliament on compliance with domestic and international human rights obligations. The Commission also contributes to the United Kingdom’s periodic reporting to UN treaty bodies and acts as the coordinating institution for the UK’s National Preventive Mechanism under the Optional Protocol to the Convention Against Torture.[177]

The EHRC operates primarily across Great Britain (England, Scotland and Wales). Northern Ireland maintains separate bodies, the Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission and the Equality Commission for Northern Ireland, reflecting the unique constitutional arrangements under the Good Friday Agreement. The EHRC nevertheless collaborates with the Northern Irish commissions on cross-jurisdictional issues and participates in the UK-wide equality and rights framework.[178]

Overall, the EHRC is one of the strongest national human rights institutions in Europe, combining regulatory, enforcement, investigative, policy and monitoring powers within a single statutory body.

Challenges

Human Rights Commissions in India, comprising the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) and the State Human Rights Commissions (SHRCs), continue to face deep structural and operational challenges that impede their ability to perform the functions envisaged under the Protection of Human Rights Act 1993. These constraints include chronic deficits in institutional capacity, limited investigative strength, inadequate funding, inconsistent transparency, and uneven public accessibility. Together, these factors prevent the commissions from translating their broad statutory mandate into effective and timely human rights protection.

Severe Capacity and Resource Deficits

The India Justice Report 2025 identifies persistent under-resourcing as one of the most significant obstacles confronting SHRCs, noting that deficits in human resources, infrastructure and budgets “fundamentally shape the structure and efficiency” of justice-sector institutions, including human rights commissions. Vacancies across sanctioned posts, particularly among investigators and administrative personnel, substantially diminish institutional capability and slow down inquiries. These gaps, the report stresses, reflect structural weaknesses rather than temporary shortages, and have long-term impacts on the ability of commissions to carry out independent, rigorous investigations.[179]

High Disposal Rates Concealing Superficial Outcomes

Although disposal rates for SHRCs frequently exceed 80 per cent, the India Justice Report 2025 warns that such figures can be misleading. The report observes that many of these disposals occur in limine, with complaints being rejected at the preliminary stage without substantive examination. As the report explains, the high disposal rate “is mainly made up of complaints that are rejected at the outset rather than reflecting institutional effort at comprehensive and early resolution,” thereby obscuring the limited depth of inquiry and masking the absence of meaningful redressal mechanisms.[180]

Weak Transparency and Limited Public Accountability

The India Justice Report 2025 notes substantial transparency deficits across several SHRCs. Many do not publish timely annual reports, fail to provide detailed case statistics, and offer incomplete information on staffing, diversity, case types or institutional performance. The report further documents instances where SHRCs showed “a reluctance to respond to RTI queries that require little more than access to public data,” inhibiting public scrutiny and weakening institutional accountability.[181]

Limited Accessibility and Digital Infrastructure

According to the India Justice Report 2025, many SHRCs lack functional, user-friendly websites, and several provide little more than basic contact details. Except for a handful of states, online complaint mechanisms are either unavailable or poorly maintained. The report notes that minimal digital integration reduces accessibility, especially for individuals in rural and remote regions who rely on online platforms to file complaints or track case progress. Poor digital infrastructure also undermines transparency and significantly weakens public engagement with human rights institutions.[182]

Inadequate Monitoring and Field-Level Oversight

The India Justice Report 2025 highlights that SHRCs conduct very few visits to custodial institutions, despite statutory obligations to inspect prisons, police lock-ups, juvenile homes and mental health facilities. In 2023–24, only 80 visits were reported across 353 institutions nationwide, indicating minimal on-ground oversight. The report emphasises that such limited monitoring restricts the ability of commissions to detect violations, address systemic problems in detention spaces and hold authorities accountable for custodial conditions.[183]

Budget Constraints and Uneven Utilisation

The India Justice Report 2025 records wide variations in budget allocations to SHRCs across the country. Even when funds are available, many commissions fail to utilise them fully, largely due to staffing shortages, administrative delays and institutional capacity gaps. Low budget utilisation weakens the ability of commissions to conduct investigations, undertake field visits, modernise digital infrastructure or carry out outreach programmes. These fiscal inconsistencies reinforce broader structural weaknesses and prevent SHRCs from fulfilling core statutory functions.[184]

Gender Imbalances and Diversity Gaps

The India Justice Report 2025 highlights persistent disparities in representation across SHRC staffing structures, noting underrepresentation of women, Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, Other Backward Classes and persons with disabilities. Such imbalances weaken the inclusiveness and responsiveness of human rights institutions. The report notes that improving representation across justice-sector agencies is essential for ensuring equal access, institutional legitimacy and greater sensitivity toward marginalised groups.[185]

Way Ahead

Strengthening the future functioning of the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) and State Human Rights Commissions (SHRCs) will require a combination of structural reform, enhanced institutional capacity and improved coordination across the broader justice system. The India Justice Report 2025 emphasises that human rights institutions do not operate in isolation and that meaningful progress depends on reinforcing the collective capacity of all justice-sector bodies. It highlights the need for sustained investment in people, infrastructure and data systems to ensure that human rights protections are accessible, responsive and effective across India.

Enhancing Human and Financial Resources

The India Justice Report 2025 identifies chronic under-resourcing as one of the most persistent obstacles faced by SHRCs and the wider justice network. It notes that many commissions continue to operate with significant vacancies in sanctioned posts, particularly among investigative staff, legal officers and administrative personnel. These shortcomings restrict the capacity of commissions to conduct timely inquiries, carry out field inspections and process complaints efficiently. The report calls for deliberate expansion of staffing strength, systematic recruitment and specialised training designed to build professional expertise in areas such as custodial monitoring, forensic assessment and rights-based investigation.[186]

Improving financial capacity is equally essential. The India Justice Report 2025 observes that inadequate budgets, coupled with delays in fund utilisation, have long impeded institutional performance. It emphasises the need for predictable annual funding, strengthened planning and targeted spending on investigation, digital infrastructure and public outreach.[187]

Improving Transparency and Public Data

A central reform priority highlighted by the India Justice Report 2025 is the establishment of transparent and standardised data practices within human rights commissions. The report notes that publicly available information on complaints, pendency, case outcomes, staff diversity and institutional performance varies widely among SHRCs. It emphasises that regular publication of annual reports, consistent website updates and increased responsiveness to information requests are essential to building public trust and enabling evidence-based policymaking. The India Justice Report 2025 stresses that accessible, disaggregated and reliable data form the foundation of any effective reform strategy, allowing policymakers and researchers to identify structural gaps and evaluate progress. [188]

Strengthening Digital Infrastructure

The India Justice Report 2025 recognises that digital systems remain uneven across SHRCs, limiting public accessibility and administrative efficiency. Strengthening digital infrastructure includes developing fully functional, user-friendly websites, expanding online complaint portals, improving digital archiving of cases and establishing integrated platforms for case monitoring. According to the India Justice Report 2025, deeper technological adoption can reduce administrative delays, enhance inter-institutional coordination and widen access to justice, particularly for geographically remote or marginalised communities .[189]

Expanding Monitoring and Field-Level Oversight

The India Justice Report 2025 highlights that improving oversight of custodial institutions, including prisons and police lock-ups, is essential for fulfilling the statutory mandates of human rights commissions. It notes that many commissions undertake very few institutional visits each year, limiting their ability to detect and prevent violations. Strengthening field-level monitoring requires regular inspections, greater investigative autonomy and the establishment of specialised units dedicated to surprise visits and follow-up action. The India Justice Report 2025 further emphasises that strengthening monitoring is vital for ensuring compliance with human rights standards and improving conditions in closed institutions.[190]

Promoting Diversity and Inclusive Representation

According to the India Justice Report 2025, meaningful institutional reform must also include improving representation within human rights commissions. The report documents persistent disparities in the presence of women, Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, Other Backward Classes and persons with disabilities across the justice system. It argues that enhancing representation within commissions, particularly in investigative and leadership roles, is essential to strengthening institutional legitimacy, improving sensitivity to vulnerable groups and ensuring equal access to justice.[191]

Coordinating System-Wide Reform

The India Justice Report 2025 repeatedly emphasises that progress within human rights commissions is inseparable from broader systemic reform across all justice institutions. It notes that justice delivery “is not accomplished in silos” and requires a coordinated network of functioning institutions that collectively uphold the rule of law.[192] Enhanced cooperation between SHRCs, NHRC, police, judiciary, legal aid authorities and prison departments is therefore essential to ensuring that findings, recommendations and investigations lead to concrete remedial action.

Ensuring Political Commitment and Public Engagement

Finally, the India Justice Report 2025 stresses that long-term institutional transformation requires sustained political will and active public engagement. It describes justice reform as a “societal demand” that must be supported through clear governmental prioritisation, regular public scrutiny and stronger civil-society participation. The report concludes that accessible, predictable and transparent institutions depend on continuous reform efforts rather than sporadic or crisis-driven interventions.[193]

Also known as

National human rights Institutes (NHRIs)

References

- ↑ The Protection of Human Rights Act (PHRA) 1993.

- ↑ The Protection of Human Rights Act (PHRA) 1993, § 2(1)(d).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act, 1993https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/15709/1/A1994____10.pdf

- ↑ The Protection of Human Rights Act, 1993 (with Amendment Act, 2006);The Protection of Human Rights (Amendment) Act, 2019

- ↑ Universal Declaration of Human Rights | United Nations. [online] United Nations. Available at: https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights [Accessed 27 Dec. 2023].

- ↑ Gagandeep Dhaliwal, ‘Organization, Functions and Powers of National Human Rights Commission (NHRC): An Overview’ (2025) 30(10) IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science 68. <<https://www.iosrjournals.org/iosr-jhss/papers/Vol.30-Issue10/Ser-1/H3010016873.pdf>> last accessed on 23 November 2025

- ↑ Vision & Mission | National Human Rights Commission India. [online] Available at: https://nhrc.nic.in/about-us/vision-and-mission [Accessed 27 Dec. 2023].

- ↑ About the Organisation | National Human Rights Commission India. [online] Available at: https://nhrc.nic.in/about-us/about-the-Organisation [Accessed 27 Dec. 2023].

- ↑ The Protection of Human Rights Act (PHRA) 1993, § 2(d).

- ↑ The Protection of Human Rights Act (PHRA) 1993, § 12.

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993 s 3

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993 s 2(d)

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993 ss 11–12

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993 s 12

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993 s 12(f)

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 12(a).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 12(a)(ii).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 12(b).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 12(c).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 12(d).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 12(e).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 12(f).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 12(g).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 12(h).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 12(i).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 12(j).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 13(1)(a).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 13(1)(b).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 13(1)(c).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 13(1)(d).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 13(1)(e).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 13(1)(f).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 13(2).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 13(2).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 13(3).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 13(4).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 13(5).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 13(6).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 13(7).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 14(1).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 14(2)(a).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 14(2)(b).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 14(2)(c).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 14(3).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 14(4).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 14(5).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 15.

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 16.

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 16 proviso.

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 17(i).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 17 proviso (a).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 17 proviso (b).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 17(ii).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 18(a)(i).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 18(a)(ii).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 18(a)(iii).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 18(b).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 18(c).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 18(d).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 18(e).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 18(f).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 19(1)(a).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 19(1)(b).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 19(2).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 19(3).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 19(4).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 20(1).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 20(2).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993 s 3(2)(a)–(c)

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993 s 3(2)(d)

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993 s 3(3)

- ↑ Section 3 of Protection of Human Rights Act, 1993

- ↑ The Protection of Human Rights (Amendment) Bill, 2019, s 3

- ↑ The Protection of Human Rights (Amendment) Bill, 2019, s 3

- ↑ The Protection of Human Rights (Amendment) Bill, 2019, s 3

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993 s 4(1)

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993 s 4(1) proviso

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993 s 4(1) second proviso

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993 s 4(2)

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993 s 6(1)–(2)

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993 s 5

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993 s 3(4)

- ↑ NHRC India Handbook p. 6 <https://nhrc.nic.in/assets/uploads/publication/NHRCindia.pdf>

- ↑ NHRC India Handbook p. 6

- ↑ NHRC India Handbook p. 7

- ↑ NHRC India Handbook p. 6

- ↑ NHRC India Handbook p. 6

- ↑ NHRC India Handbook p. 7

- ↑ NHRC India Handbook p. 7

- ↑ NHRC India Handbook p. 7

- ↑ NHRC India Handbook p. 7

- ↑ NHRC India Handbook p. 7

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 21

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 21(2)(a).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 21(2)(b).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 21(2)(c).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 21(3).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 21(4).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 21(5).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 22(1).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, Proviso to s 22(1).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, Proviso to s 22(1).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 29.

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 12(a).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 12(c).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 12(d).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 12(e).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 12(g)–(i).

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 13.

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 14.

- ↑ Protection of Human Rights Act 1993, s 18.

- ↑ IJR Report 2025 p 141 https://indiajusticereport.org/files/IJR%204_Full%20Report_English%20(1).pdf

- ↑ IJR Report 2025 p 141

- ↑ IJR Report 2025 p 141

- ↑ IJR Report 2025 p 141

- ↑ IJR Report 2025 p 141

- ↑ IJR Report 2025 p 141

- ↑ IJR Report 2025 p 167

- ↑ IJR Report 2025 p 141

- ↑ IJR Report 2025 p 167

- ↑ IJR Report 2025 p 142

- ↑ IJR Report 2025 p 143

- ↑ IJR Report 2025 p 166

- ↑ IJR Report 2025 p 166

- ↑ IJR Report 2025 p 143

- ↑ IJR Report 2025 p 143

- ↑ IJR Report 2025 p 143

- ↑ IJR Report 2025 p 142

- ↑ IJR Report 2025 p 143

- ↑ https://nhrc.nic.in/

- ↑ https://nhrc.nic.in/

- ↑ https://nhrc.nic.in/

- ↑ https://nhrc.nic.in/

- ↑ https://nhrc.nic.in/

- ↑ https://nhrc.nic.in/

- ↑ https://nhrc.nic.in/

- ↑ https://nhrc.nic.in/

- ↑ https://nhrc.nic.in/

- ↑ National Informatics Centre, ‘HRCNet Portal Overview’ (HRCNet) <https://hrcnet.nic.in/hrcnet/public/home.aspx> accessed 24 November 2025.

- ↑ National Human Rights Commission, ‘About HRCNet’ (HRCNet) <https://hrcnet.nic.in/nhrc/> accessed 24 November 2025.

- ↑ National Informatics Centre, ‘User Manual (English): Procedure to Lodge Complaints’ (PDF, HRCNet) <https://hrcnet.nic.in/HRCNet/help/UserManual_English.pdf> accessed 24 November 2025.

- ↑ National Informatics Centre, ‘User Manual (English): Procedure to Lodge Complaints’ (PDF, HRCNet) <https://hrcnet.nic.in/HRCNet/help/UserManual_English.pdf> accessed 24 November 2025.

- ↑ HRCNet, ‘Search Complaint’ (HRCNet) <https://hrcnet.nic.in/HRCNet/public/SearchComplaint.aspx> accessed 24 November 2025.

- ↑ NHRC, ‘Case Status and Case Management Tools’ (HRCNet) <https://hrcnet.nic.in/HRCNet/public/CaseStatus.aspx> accessed 24 November 2025.

- ↑ National Informatics Centre, ‘HRCNet Portal Overview’ (HRCNet) <https://hrcnet.nic.in/hrcnet/public/home.aspx> accessed 24 November 2025.

- ↑ HRCNet, ‘Dashboard’ (HRCNet) <https://hrcnet.nic.in/dashboard/index.aspx> accessed 24 November 2025.

- ↑ National Human Rights Commission, ‘How to File an Online Complaint’ (NHRC) <https://nhrc.nic.in/how-to-file-an-online-complaint> accessed 24 November 2025.

- ↑ NHRC, ‘Guidelines for Complaint Registration’ (PDF, HRCNet) <https://hrcnet.nic.in/HRCNet/help/Guidelines_for_complaint_registration.pdf> accessed 24 November 2025.

- ↑ National Informatics Centre, ‘HRCNet Portal Overview’ (HRCNet) <https://hrcnet.nic.in/hrcnet/public/home.aspx> accessed 24 November 2025.

- ↑ Assessing the Effectiveness of the National Human Rights Commission, India, vis-à-vis the Paris Principles Relating to the Status of National Human Rights Institutions | The Age of Human Rights Journal. [online] Available at: https://revistaselectronicas.ujaen.es/index.php/TAHRJ/article/view/7719/7703 [Accessed 20 Dec. 2023].

- ↑ UN OHCHR, National Human Rights Institutions: History, Principles, Roles and Responsibilities (2010) p 2. https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Publications/PTS-4Rev1-NHRI_en.pdf

- ↑ C Raj Kumar, ‘National Human Rights Institutions: Good Governance Perspectives on Institutionalization of Human Rights’ (2003) 19 American University International Law Review 259, 266.https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?path_info=19_2_2.pdf&&context=auilr&&article=1164&&=&&sei-redir=1&referer=https%253A%252F%252Fwww.google.com%252Furl%253Fq%253Dhttps%253A%252F%252Fdigitalcommons.wcl.american.edu%252Fcgi%252Fviewcontent.cgi%25253Fparams%25253D%252Fcontext%252Fauilr%252Farticle%252F1164%252F%252526path_info%25253D19_2_2.pdf%2526sa%253DU%2526ved%253D2ahUKEwjl94TGwouRAxUnQPUHHZk5BycQFnoECCkQAQ%2526usg%253DAOvVaw2USd5B_OtCCG13xT2oWmHg#search=%22https%3A%2F%2Fdigitalcommons.wcl.american.edu%2Fcgi%2Fviewcontent.cgi%3Fparams%3D%2Fcontext%2Fauilr%2Farticle%2F1164%2F%26path_info%3D19_2_2.pdf%22

- ↑ C Raj Kumar (n 2) 266.

- ↑ UN OHCHR (n 1) p 31.

- ↑ UN OHCHR (n 1) p 7.

- ↑ UN OHCHR (n 1) p 44.

- ↑ UN OHCHR (n 1) p 2.

- ↑ UN OHCHR (n 1) p 4.

- ↑ C Raj Kumar, ‘National Human Rights Institutions: Good Governance Perspectives on Institutionalization of Human Rights’ (2003) 19 American University International Law Review 259, 266.https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?path_info=19_2_2.pdf&&context=auilr&&article=1164&&=&&sei-redir=1&referer=https%253A%252F%252Fwww.google.com%252Furl%253Fq%253Dhttps%253A%252F%252Fdigitalcommons.wcl.american.edu%252Fcgi%252Fviewcontent.cgi%25253Fparams%25253D%252Fcontext%252Fauilr%252Farticle%252F1164%252F%252526path_info%25253D19_2_2.pdf%2526sa%253DU%2526ved%253D2ahUKEwjl94TGwouRAxUnQPUHHZk5BycQFnoECCkQAQ%2526usg%253DAOvVaw2USd5B_OtCCG13xT2oWmHg#search=%22https%3A%2F%2Fdigitalcommons.wcl.american.edu%2Fcgi%2Fviewcontent.cgi%3Fparams%3D%2Fcontext%2Fauilr%2Farticle%2F1164%2F%26path_info%3D19_2_2.pdf%22

- ↑ UN OHCHR (n 1) p 13.

- ↑ UN OHCHR (n 1) p 44.

- ↑ Tiwana, M. (2004). Needed: More Effective Human Rights Commissions in India. [online] Available at: https://www.humanrightsinitiative.org/publications/nl/articles/india/needed_more_effective_hr_comm_india.pdf.

- ↑ Tiwana, M. (2004). Needed: More Effective Human Rights Commissions in India. [online] Available at: https://www.humanrightsinitiative.org/publications/nl/articles/india/needed_more_effective_hr_comm_india.pdf.

- ↑ Civil Rights Act of 1957, Pub L No 85-315, 71 Stat 634 codified at 42 USC §1975.

- ↑ US Commission on Civil Rights, ‘Our Mission’ (USCCR) <https://www.usccr.gov/about/mission> accessed 25 November 2025.

- ↑ US National Archives, ‘Records of the US Commission on Civil Rights’ (Record Group 453) <https://www.archives.gov/research/guide-fed-records/groups/453> accessed 25 November 2025.

- ↑ Congressional Research Service, ‘The US Commission on Civil Rights: Overview and Current Issues’ (CRS Report R47009, 2022) 3–7, available via the US Government Publishing Office: <https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CRS-R47009/pdf/CRS-R47009.pdf> accessed 25 November 2025.

- ↑ US Government Publishing Office, ‘US Commission on Civil Rights: Background and Statutory Authorities’ (GPO, 2021) 4–6 <https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-USCCR-Background/pdf/GPO-USCCR-Background.pdf> accessed 25 November 2025.

- ↑ Canadian Human Rights Act RSC 1985, c H-6, ss 2–3.

- ↑ Employment Equity Act SC 1995, c 44, ss 4–6.

- ↑ Canadian Human Rights Commission, ‘About the Commission’ (Government of Canada) <https://www.chrc-ccdp.gc.ca/en/about-us/about-commission> accessed 25 November 2025.

- ↑ Canadian Human Rights Commission, ‘Reports to Parliament’ (Government of Canada) <https://www.chrc-ccdp.gc.ca/en/resources/reports-parliament> accessed 25 November 2025.

- ↑ Government of Canada, ‘Canada’s Human Rights System’ (Department of Justice) <https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/csj-sjc/hr-dp/index.html> accessed 25 November 2025.

- ↑ Equality Act 2006 (UK) ss 1–3.

- ↑ Equality and Human Rights Commission, ‘Who We Are’ (EHRC) <https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/en/about-us/who-we-are> accessed 25 November 2025.

- ↑ Equality Act 2006 (UK) ss 20–32.

- ↑ Equality and Human Rights Commission, ‘Our Human Rights Work’ (EHRC) <https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/en/human-rights/our-human-rights-work> accessed 25 November 2025.

- ↑ UK Government, ‘Human Rights and Equality Bodies in the UK’ (Government Equalities Office) <https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/government-equalities-office> accessed 25 November 2025.

- ↑ India Justice Report 2025, ‘National Deficits’ 5 <https://indiajusticereport.org/files/IJR%204_Full%20Report_English%20(1).pdf> accessed 24 November 2025.

- ↑ India Justice Report 2025, ‘SHRCs: Constrained by Capacity Deficits’ 8 <https://indiajusticereport.org/files/IJR%204_Full%20Report_English%20(1).pdf> accessed 24 November 2025.

- ↑ India Justice Report 2025, ‘SHRCs: Constrained by Capacity Deficits’ 8 <https://indiajusticereport.org/files/IJR%204_Full%20Report_English%20(1).pdf> accessed 24 November 2025.

- ↑ India Justice Report 2025, ‘SHRCs: Constrained by Capacity Deficits’ 8 <https://indiajusticereport.org/files/IJR%204_Full%20Report_English%20(1).pdf> accessed 24 November 2025.

- ↑ India Justice Report 2025, ‘Visits to Jails & Other Institutions 2023–24’ 144–146 <https://indiajusticereport.org/files/IJR%204_Full%20Report_English%20(1).pdf> accessed 24 November 2025.

- ↑ India Justice Report 2025, ‘National Deficits’ 12 <https://indiajusticereport.org/files/IJR%204_Full%20Report_English%20(1).pdf> accessed 24 November 2025.

- ↑ India Justice Report 2025, ‘Diversity and Disabilities’ 5–6 <https://indiajusticereport.org/files/IJR%204_Full%20Report_English%20(1).pdf> accessed 24 November 2025.

- ↑ India Justice Report 2025, ‘National Deficits’ 5, <https://indiajusticereport.org/files/IJR%204_Full%20Report_English%20(1).pdf> accessed 24 November 2025.

- ↑ India Justice Report 2025, ‘India Justice Report 2025’ iv, <https://indiajusticereport.org/files/IJR%204_Full%20Report_English%20(1).pdf> accessed 24 November 2025.

- ↑ India Justice Report 2025, ‘Conclusion’ 9, <https://indiajusticereport.org/files/IJR%204_Full%20Report_English%20(1).pdf> accessed 24 November 2025.

- ↑ India Justice Report 2025, ‘Introduction’ 7–9, <https://indiajusticereport.org/files/IJR%204_Full%20Report_English%20(1).pdf> accessed 24 November 2025.

- ↑ India Justice Report 2025, ‘Visits to Jails & Other Institutions 2023–24’ 144–146, <https://indiajusticereport.org/files/IJR%204_Full%20Report_English%20(1).pdf> accessed 24 November 2025.

- ↑ India Justice Report 2025, ‘Diversity and Disabilities’ 5–6, <https://indiajusticereport.org/files/IJR%204_Full%20Report_English%20(1).pdf> accessed 24 November 2025.

- ↑ India Justice Report 2025, ‘National Deficits’ 7, <https://indiajusticereport.org/files/IJR%204_Full%20Report_English%20(1)%29.pdf> accessed 24 November 2025.

- ↑ India Justice Report 2025, ‘Conclusion’ 9, <https://indiajusticereport.org/files/IJR%204_Full%20Report_English%20(1)%29.pdf> accessed 24 November 2025.