Information Commission

This page is now open for community updates

What is the Information Commission

Information Commissions are statutory, quasi-judicial bodies established under the Right to Information Act, 2005.[1]They serve as the final appellate authorities to decide on appeals and complaints of citizens who have been denied their right to information under the law.[2] The Central and State Information Commissions (CICs and SICs) are given the power to resolve complaints or appeals, as preferred to it under Sections 18 and 19 of the Act, and to render decisions concerning the same.[3]

Official Definition of the Information Commission

The Central Information Commission (CIC), as defined under section 2(b) of the Right to Information Act, 2005, is the statutory body constituted under section 12(1). At the state level, section 2(k) defines the State Information Commission as the body constituted under section 15(1) of the Act. This provision requires every state government to establish the State Information Commission through notification in the Official Gazette, empowering it to discharge the functions and exercise the powers assigned under the Act.

The Central Information Commission (CIC) is constituted by the central government under section 12 of the RTI Act.[4] It oversees the Act’s application to all central government bodies and agencies, hears complaints and second appeals from citizens, and ensures central agencies comply with the law.Each state has its own State Information Commission (SIC), established under section 15 of the RTI Act.[5] SICs perform the same functions for state government departments and agencies, adjudicating complaints and appeals related to information disclosure within their respective states. Thus, these commissions function together as the protectors of the right to information, thereby maintaining the public's access to the information held by the government at both the central and state levels.

Information Commission as defined in Legislation

Information commissions operate legally as statutory rather than constitutional entities. However, their actions directly safeguard a fundamental right, establishing what academics refer to as a "constitutional umbilical link" to Article 19. The distinction between statutory tribunals and constitutional authority is muddled by their quasi-judicial character and civil court-like powers. The jurisdiction of the Central Information Commission (CIC) and State Information Commissions (SICs) is derived from sections 12 to 15 of the Right to Information Act, 2005. Sections 18, 19, and 20 confer upon these Commissions the status of statutory bodies with quasi-judicial powers. Under section 18, the Commissions are empowered to receive and adjudicate complaints regarding non-appointment of Public Information Officers, failure to provide information within prescribed timelines, or provision of incomplete or misleading information. Section 19 vests appellate jurisdiction to entertain second appeals against orders of the First Appellate Authority.

Section 12(1) mandates the Central Government to establish the Central Information CommissionCommission by notification in the Official Gazette, vesting it with the powers and functions prescribed under the Act.

Composition

Section 12(2) provides for the composition of Central Information Commission, it states that the Central Information Commission shall consist of the Chief Information Commissioner (CIC) and such number of Central Information Commissioners not exceeding 10 as may be deemed necessary. The Chief Information Commissioner and Information Commissioners, as defined in section 2(d), are the officials appointed under sub-section (3) to head and constitute the Commission. Along the same lines, Section 15(2) provides for the composition of State Information Commission, it states that State Information Commission shall consist of the State Chief Information Commissioner, and such number of State Information Commissioners, not exceeding ten, as may be deemed necessary. The State Chief Information Commissioner and State Information Commissioner, as defined in Section 2(k), are the officials appointed under sub-section (3) of section 15.

Information Commissioners

Appointment Process

Section 12(3), which says that the Chief Information Commissioner and Information Commissioners shall be appointed by the President on the recommendation of a committee consisting of—

- (i) the Prime Minister, who shall be the Chairperson of the committee;

- (ii) the Leader of Opposition in the LokSabha ; and

- (iii) a Union Cabinet Minister to be nominated by the Prime Minister.

Section 15(3), which states that the State Chief Information Commissioner and the State Information Commissioners shall be appointed by the Governor on the recommendation of a committee consisting of—

- (i) the Chief Minister, who shall be the Chairperson of the committee;

- (ii) the Leader of Opposition in the Legislative Assembly; and

- (iii) a Cabinet Minister to be nominated by the Chief Minister.

Terms of Office (include salary, tenure, etc.)

In order to provide parity and tenure security, Sections 13(5) and 16(5) initially compared the pay and terms of service of information commissioners to those of Election Commissioners and Supreme Court judges. However, the RTI (Amendment) Act of 2019 gave the Central Government the authority to set executive rules for tenure and compensation.[6] Later regulations shortened the term to three years and set monthly salaries at ₹2.25–2.50 lakh, allowing the Centre to modify or loosen terms as needed. [7]Opponents contend that this modification seriously compromises the commissions' independence and turns them from impartial watchdogs into executive departments.

Powers and Function of Information Commissioner

Section 18 of the RTI Act, 2005, enshrines the power and functions of the information commissioner, both state and central categorically. The function of the information commissioner is to adjudicate and resolve the complaints received by any applicant against any appeal, CPIO, or PIO.

The information commissioner is empowered to receive and inquire into complaints relating to refusal of access to information, inability to file RTI requests, non-response within the prescribed period, unreasonable fee demands, or any other matter relating to seeking information under the Act.[8]The information commissioner will only take action if anyone is allowed to give access to any information, despite that for being there for public usage.

Under the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908, they also have the power to issue a summons or call for evidence to investigate complaints.[9]This includes the authority to require the production of documents, examine witnesses on oath, and conduct hearings as deemed necessary.[10]

The commissioner can also order disclosure, impose penalties for non-compliance, and recommend disciplinary action against errant officials where malafide denial or delay is found.[11]Additionally, the information commissioner can secure compliance of orders and ensure transparency by directing systemic changes within public authorities where needed.[12]

Appeal

The Right to Information Act, 2005 lays down a two-stage appeals framework to safeguard the rights of citizens requesting information. An unsatisfied applicant with the Public Information Officer's (PIO) response or in case of no reply within the stipulated time, may first appeal to the First Appellate Authority of the same public authority, who is senior in rank as compared to the PIO. The applicant, in case of non-satisfaction with the First Appellate Authority’s decision, can make a second appeal to the Central or State Information Commission within ninety days although the delay in filing is allowed for reasonable grounds. The Commission adopts a judiciary-like but less formal approach wherein, it hears the parties before passing the orders. It can order the disclosure of the information, issuance of a correction letter by the PIO to the complainant, or rejection of the application, and the decisions of the commission are conveyed in writing to all the concerned parties.[13]

Penalty

According to Section 20 of the Right to Information Act, 2005, the Information Commissions have the power to hold accountable Public Information Officers (PIOs) for their failures to provide information. When a PIO refuses a request without justification, gives false or misleading information, or in any other way delays the disclosure beyond the time limit set by the law without a good cause, the Commission may impose a monetary penalty of ₹250 per day, up to a maximum of ₹25,000 for each case. Moreover, where there are serious or repeated instances of the violations of the PIO, the Commission can also suggest the initiation of disciplinary proceedings against him/her. Although the existence of this coercive power is meant to serve as a deterrent and hence lead to better compliance of the RTI system, studies and official reports say that penalties are rarely imposed in proportion to the number of violations that have been established.[14]

Reporting

According to Section 25 of the Right to Information Act, 2005, each Central and State Information Commission is required to produce an Annual Report that describes the Act's performance and implementation. This covers the overall quantity of information requests that are received, approved, or denied; the rationale behind the denials; the quantity of appeals that are filed and their results; the sanctions levied against officials; and the actions taken by public authorities to encourage accountability and transparency. [15]The necessary information must be provided by each Ministry and Department in order for this report to be put together. To ensure supervision, review, and remedial action where needed, the Central and State Governments must then present these reports to Parliament and the corresponding State Legislatures.[16]

The competent authority—Parliament, State Legislatures, the Supreme Court, or High Courts—is also authorised by Section 25 to establish regulations for the Act's administration within their respective jurisdictions.[17] These regulations could outline the process for making an information request, the costs involved, the appeals process, and how Information Commissions operate.[18] The Right to Information Bill 2004's democratic goals are supported by these provisions, which taken together institutionalise accountability, encourage administrative flexibility, and institutionalise transparency.[19]

As defined in Official Government Report

Parliamentary Committee Report

The Right to Information Bill, 2004 was reviewed by the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Personnel, Public Grievances, Law, and Justice, which also made important recommendations about the composition and independence of the Central Information Commission. To effectively carry out the goals of the legislation, the Committee stressed that the Commission should operate "with utmost independence and autonomy".[20] The Committee recommended that "the Information Commissioner and Deputy Information Commissioners, status of the Chief Election Commissioner and the Election Commissioner, respectively"be granted in order to elevate the position of Information Commissioners to that of constitutional authorities.[21] The goal of this promotion was to guarantee operational independence free from political meddling. The Committee took note of the Bill's provision for a selection committee that would include the Chief Justice of India, the Leader of the Opposition, and the Prime Minister. [22] It did, however, raise concerns about limitations on eligibility criteria and suggested broadening the scope to include "law, science and technology, social service, management, journalism, mass media" in addition to administration and governance.[23] The Committee also recommended eliminating provisions that limited post-tenure employment and subjected Deputy Information Commissioners to directives from the Central Government, as they were seen as obstacles to true independence.[24] The Committee's vision for an independent, empowered Commission that could implement citizens' right to information was reflected in these recommendations.

The CHRI's Submission Regarding the Recommendations of the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Personnel, Public Grievances, Law and Justice on the Right to Information Bill, 2004 identifies several key issues concerning the design and operation of the Information Commissions under the Right to Information Bill, 2004. It criticizes the lack of clarity in jurisdiction, emphasizing the need to clearly demarcate the authority of Central and State Information Commissions to avoid overlap and confusion. The submission highlights problems with the appointment process, noting the absence of transparent procedures, public consultation, and integrity-based selection criteria, and warns that political or bureaucratic dominance could erode public confidence. It raises concern about the autonomy of Information Commissions, as the Bill allows government interference in office establishment, staffing, and budgeting — thereby compromising independence. The document urges that the Commissions should be empowered to hire their own staff, free from bureaucratic deputation, to ensure impartiality and efficiency. It further points to the failure to include provisions allowing Commissions to initiate suo motu investigations, limiting their ability to address systemic non-compliance. Additionally, the report calls for enhanced penalty powers so that Commissions can impose personal fines for delays or obstruction and recommends requiring their reports to be submitted to Parliament for review by a Standing Committee. Finally, it criticizes the Bill for giving the government control over framing rules for the Commission, arguing that Commissions must have rule-making power to maintain operational independence.[25]

As defined in Case Laws

Anjali Bhardwaj v. Union of India (2019)

In Anjali Bhardwaj v. Union of India,[26] a critical legal issue examined by the Supreme Court was the government’s failure to promptly appoint Information Commissioners, resulting in significant delays and backlogs that undermined the statutory right to information. The petition raised questions about whether the lack of timely appointments violated both the letter and spirit of the RTI Act’s mandate for independent, quasi-judicial oversight. In its decision, the Court underscored that the proper functioning of Information Commissions is fundamental to transparency and accountability in governance. Directing the government to advertise vacancies, disclose selection criteria, and ensure diversity among commission members, the judgment advanced an academic understanding of the commissions as essential institutions for democratic legitimacy. The ruling cautioned that persistent vacancies and opaque appointments contravene citizens’ rights and the statutory design of the RTI regime, thereby significantly weakening the machinery created for public accountability and open governance.

In this case, the Supreme Courtmade strong observations about the tendency of the government to only appoint former or serving government employees as information commissioners, even though the RTI Act states that commissioners should be chosen from diverse backgrounds and fields of experience. The relevant extracts are-

“39. … However, a strange phenomenon which we observe is that all those persons who have been selected belong to only one category, namely, public service, i.e., they are the government employees. It is difficult to fathom that persons belonging to one category only are always be found to be more competent and more suitable than persons belonging to other categories. In fact, even the Search Committee which short-lists the persons consist of bureaucrats only. For these reasons, official bias in favour of its own class is writ large in the selection process.”

Union of India v Namit Sharma (2013)

The Supreme Court in Union of India v. Namit Sharma[27] took cognisance of the functioning of commissions across the country, including the poor quality of orders passed by ICs, directed that chief information commissioners must ensure that matters involving intricate questions of law are heard by commissioners who have legal expertise.

Official Databases on Information Commissioner

Annual Report of CIC

The Annual report publishes data on the number of RTI requests received, amount of penalties imposed, no. of first appeals received and disposed of, and reasons for the rejection of the request. The data is further classified based on ministries and Departments.

Annual Report of SIC

The publication and availability of annual reports, a crucial statutory mechanism for guaranteeing accountability and transparency under the Right to Information Act of 2005, vary greatly amongst State Information Commissions (SICs) in India, according to a recent review. Just a small number of commissions, such as those in Assam, Chhattisgarh, Gujarat, Mizoram, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, West Bengal, and the Central Information Commission (CIC), regularly post current annual reports and statistical data on their websites as of October 2024, allowing for significant public scrutiny of RTI implementation.[28]

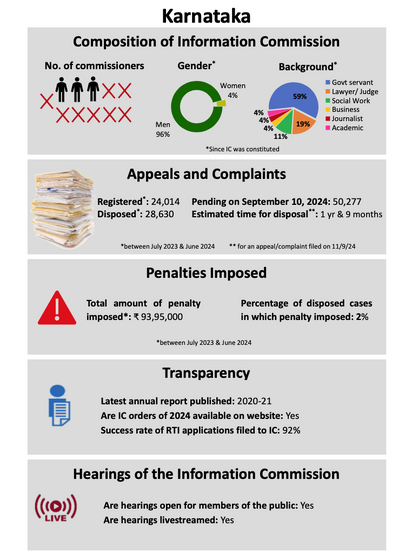

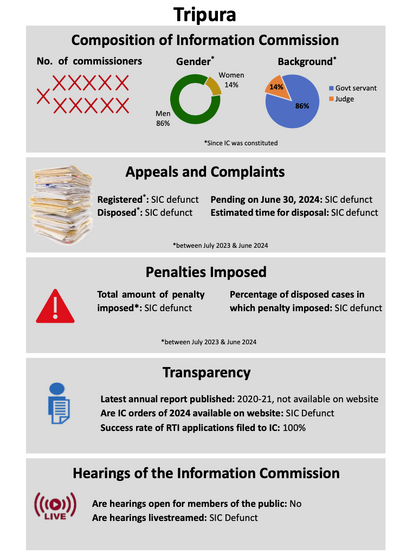

Online databases of annual reports are also kept by states like Karnataka, Odisha, and Sikkim, though some of them are out of date. On the other hand, most SICs exhibit inadequate compliance. While Kerala, Manipur, Nagaland, and Uttarakhand reportedly prepare reports but do not make them publicly available, Andhra Pradesh and Telangana have not released a single annual report since their creation in 2017. Other states have not updated their reports for a number of years, including Bihar (last published 2017–18), Jharkhand (2018), Goa (2020–21), and Tripura (2020–21). Notably, Telangana and Jharkhand have been declared functionally defunct because they did not resolve any cases during the review period.[29]

Moreover, functionality assessments based on the availability of SIC orders and disposal statistics reveal further inconsistencies, even among those that publish reports. Overall, compliance with statutory reporting obligations remains uneven and often superficial—impeding citizen oversight and weakening the transparency framework envisioned by the RTI Act. Independent audits consistently emphasise that digital disclosure, timely publication, and proactive transparency are indispensable best practices that remain far from universally adopted.[29]

Database Maintained by Non- Government Bodies

Peoples’ Assessment of the RTI Regime in India (SNS)

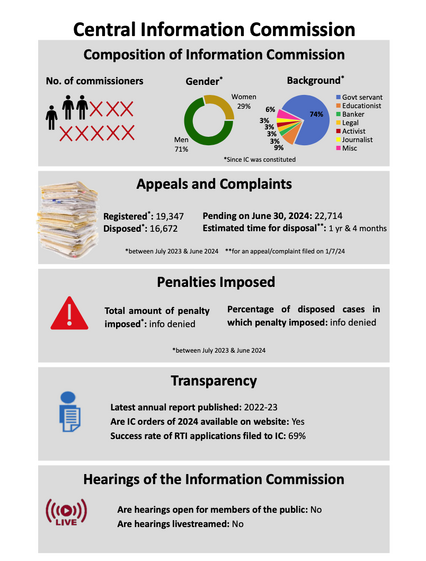

The Satark Nagrik Sangathan (SNS) report card of Information Commissions in India assesses the functioning if Information Commissions by relying on information on the number, qualifications, and length of service of commissioners; the volume of complaints and appeals filed and resolved; the amount of fines and compensation given; and the openness of hearings and the release of yearly reports. Information was gathered until October 2024 and was complemented by official websites, yearly reports, and Supreme Court and High Court rulings that were pertinent to the implementation of RTI. According to Satark Nagrik Sangathan's (SNS) Report Card of Information Commissions in India,Data from 174 RTI applications submitted to 29 information commissions—one central and 28 state commissions—is the main source of SNS's 2023–24 assessment.[30]

Report Card of Central Information Commission

Report card of State Information Commission(s)

International Experiences

United Kingdom

The Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) is the UK’s independent regulator for data protection and information rights law, upholding information rights in the public interest, promoting openness by public bodies and data privacy for individuals. It has its head office in Wilmslow, Cheshire, and regional offices in Edinburgh, Cardiff and Belfast. (Information Commissioner’s Office 2022).[31]

The Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) upholds information rights in the public interest, promoting openness by public bodies and data privacy for individuals. (Gov.Uk, 2024)[32]The ICO enforces the UK General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the Data Protection Act 2018, and the Freedom of Information Act 2000, among other legislation, giving it powers to investigate complaints, issue guidance, conduct audits, and impose monetary penalities for violations of information rights. [33]

In addition to handling public sector transparency and individual privacy, the ICO provides advisory opinions to government, responds to data breaches, and actively supports public educations on rights and responsibilities under relevant laws. [34]The Commissioner is appointed by the Crown and serves independently, accountable directly to Parliament, and regularly submits statutory reports on the state of information rights and data protection compliance in the UK.[35]

United States of America

Freedom of Information Act, 1966 was enacted on July 4, 1966, and has been in effect since 1967. The present act established a statutory right of public access to Executive Branch information in the federal government of the USA. The FOIA provides that any person has a right, enforceable in court, to obtain access to federal agency records subject to the Act, except to the extent that any portions of such records are protected from public disclosure by one of nine exemptions. The United States Supreme Court has explained that "the basic purpose of the FOIA is to ensure an informed citizenry, vital to the functioning of a democratic society, needed to check against corruption and to hold the governors accountable to the governed." (Department of Justice Guide to the Freedom of Information Act, 2020)[36]

Federal agencies are required to respond to FOIA requests within twenty business days, and must justify in writing any withholdings based on specific exemptions.[37]If a request is denied, requesters have a statutory right to appeal administratively and ultimately to seek judicial review in federal court. [38]The FOIA is administered by agency-designated FOIA Officers, and oversight is coordinated by the Office of Information Policy (OIP) in the Department of justice, which issues government - wide interpretations and compliance guidelines. [39]

Since the 1996 E -FOIA amendments, agencies must proactively disclose frequently requested records and administrative staff are encouraged to use electronic means for both requests and disclosures. [40]The Supreme Court’s interpretation in Department of the Air Force v Rose, 425 US 352 (1976), affirms that the Act’s default is disclosure and any exemption must be narrowly constructed. [41]

Commonwealth Of Australia

As per the Australian Government's official website, Office of the Australian Information Commissioner, the Australian Information Commissioner is an Independent agency under the Attorney General’s office. The primary responsibility includes formulating privacy, freedom of information, and government information policy. That also includes the responsibility of conducting investigations, reviewing decisions, handling complaints, and providing guidance and advice.[42]

The Australian Information Commissioner protects the citizens right to access government documents under the Freedom of Information Act, 1982. It carries out strategic information management under the Australian Information Commissioner Act 2010[43].

The OAIC is comprised of the Australian Information Commissioner, the privacy Commissioner, and the freedom of information commissioner — each with distinct statutory roles and powers. [44]

Under the FOI Act 1982, the Commissioner has power to conduct merits review of government agency FOI decisions, investigate breaches, promote proactive publication of information, and issue legally binding guidelines on FOI practice.[45]The OAIC may investigate privacy breaches, data security incidents, and systemic compliance failures in both government and regulated private sector agencies. [46]The OAIC provides for independent dispute resolution, offers public education, and publishes annual reports on FOI and privacy compliance, which are tabled in Parliament for accountability. [47]

Information Commissioner of Canada

As per the Canadian Information Commissioner of the Government of Canada, the same office of the information commissioner was established in 1983 under the Access to Information Act to empower general citizens of the country to present their positions. The current information for Canada is from Caroline Maynard. The role of the Information Commissioner is to investigate the complaint received by the general citizen and to resolve the issue by negotiating with the institutions.

The office of the Information Commissioner of Canada is supported by three deputy commissioners and a staff of approximately 135.[48]The Information Commissioner is an independent Officer of Parliament, reporting directly to the House of Commons and the Senate to ensure government transparency and accountability. [49]The Commissioner investigates complaints about federal institutions’ compliance with the Access to Information Act, and may make recommendations or, if necessary, bring matters before the Federal Court for legal enforcement.[50]

In addition to resolving individual complaints, the Commissioner engages in systemic investigations, public outreach, and issues annual reports to Parliament on the performance of government bodies under the Act.[51]The office can initiate investigations on its own motion, and has the power to compel disclosure of documents, but cannot itself order the release of information—judicial intervention is required if recommendations are not accepted.[52]

Research that engages with Information Commission

Report Cards by SNS

The 2023-24 Report Card finds 2023–2024, that the right to information has become "a dead letter" in many states due to ongoing vacancies, a lack of autonomy, and concerning delays.[53] The CIC, which is the highest appellate authority, was found to be working with only a small part of its authorised staff. As of October 2024, there were only three commissioners, including the Chief, and eight positions were open.[54]There were almost 23,000 cases on the backlog. Even though the Supreme Court told the Union of India to fill vacancies within three months in Anjali Bhardwaj v. Union of India (2019), appointments were still delayed.[55] The most recent appointments in November 2023 were made by a shortened selection committee that did not include the Leader of the Opposition. This raises questions about the proper use of procedures and the power of the executive.[56] At the state level, the report painted a bleak picture: during the review period, seven commissions—in Jharkhand, Tripura, Telangana, Goa, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, and Chhattisgarh—were either entirely or temporarily shut down. [57] Karnataka, Bihar, and Odisha all had three to five year wait times for their cases to be resolved, while Maharashtra's SIC had the largest backlog, with over 1.1 lakh appeals and complaints. [58] Since 2005, women have made up just 9% of all commissioners, with the majority—57%—being retired civil servants. [59] Governments have mostly disregarded the Supreme Court's explicit directive in Union of India v. Namit Sharma (2013) that information commissions include distinguished individuals from a variety of professions, such as law, journalism, and social service.[60]

Adjudicating the RTI Act: Analysis of orders of the Central Information Commission (CES and SNS)

This 2019 report, Adjudicating the RTI Act: Analysis of orders of the Central Information Commission by Satark Nagrik Sangathan and Centre for Equity Studies analyzes the orders of the Central Information Commission under the Right to Information Act, 2005, to assess the quality and effectiveness of adjudication. It highlights critical issues including extensive delays and backlogs at the CIC, a significant number of orders lacking essential facts and clear reasoning, and frequent misapplication or inappropriate extension of legal exemptions such as sections 8 and 11 of the RTI Act. The report emphasizes that many orders do not uphold the public interest override, and penalties under section 20 are rarely imposed despite statutory provisions. It calls for reforms such as formulating uniform order-writing standards, enhancing transparency and accountability, instituting clear formats for speaking orders, and ensuring judicial rigor to strengthen compliance and public trust in the RTI transparency regime.[61]

Tilting the Balance of Power- Adjudicating the RTI Act (RaaG and SNS)

The second edition of Adjudicating the RTI Act (2017), coordinated by Shekhar Singh, Amrita Johri, and Anjali Bhardwaj of RaaG and NCPRI, offers a rigorous empirical study of nearly two thousand Information Commission orders, three hundred High Court rulings, and over thirty Supreme Court judgments interpreting the Right to Information Act, 2005. It identifies widespread shortcomings in adjudication, including inconsistency across commissions, cryptic and poorly reasoned orders, reluctance to impose legally mandated penalties, and inadequate enforcement of proactive disclosure obligations. The report exposes systemic issues such as arbitrary denials, overuse of exemptions, and disregard for the public interest override clause. It urges reforms focused on uniform interpretive standards, consistent reasoning in orders, and strengthening accountability mechanisms to ensure that adjudicatory bodies advance transparency and uphold citizens’ right to information effectively.[62]

Information Commissions and the Use of RTI Laws in India (CHRI)

The Rapid Study 2.0, released by CHRI in July 2014, is a detailed examination of the working and changes in the India’s Central and State Information Commissions over time to decide the level of compliance with the RTI regime.[63] It considers various parameters such as vacancies in commissions, and the demographic and professional backgrounds of commissioners. It also looks at the availability of local language websites, online filing of appeals/complaints, cause lists, status updates, disposal statistics, publication of annual reports, budget disclosures and asset-liability declarations.[64]

The report is a diagnostic tool to reveal systemic transparency gaps and institutional weaknesses in the information commissions and, therefore, enable the provision of targeted recommendations for reform (for instance, making it compulsory to submit the annual reports on time and to disclose the data proactively).[65] The main point of the report is to serve as an empirical baseline for which civil society, scholars and policymakers can use to track performance, identify deviations from RTI obligations and demand higher institutional accountability. It does this by setting standards for disclosure in various states, thus opening the way for more extensive institutional transparency within the RTI framework.

References

- ↑ Dhaka, R. S. (2018). The Information Commissions in India: A Jurisprudential Explication of Their Powers and Functions. Indian Journal of Public Administration, 64(4), 703-716. https://doi.org/10.1177/0019556118788481 (Original work published 2018)

- ↑ Bikranta Paul and Mante Sakachep (2023),

- ↑ (Ann Thania Alex, 2014)

- ↑ Right to Information Act 2005, s 12.

- ↑ Right to Information Act 2005, s 15.

- ↑ Right to Information (Amendment) Act 2019, No 24 of 2019, Gazette of India, 1 August 2019.

- ↑ Right to Information Rules 2019 (Department of Personnel and Training, Government of India) https://documents.doptcirculars.nic.in/D2/D02rti/RTI_Rules_2019r4jr6.pdf accessed 14 October 2025.

- ↑ Rajvir S Dhaka, ‘The Information Commissions in India: A Jurisprudential Explication of Their Powers and Functions’ (2018) 64(4) Indian Journal of Public Administration 706.

- ↑ Dhaka (n 1) 707.

- ↑ Dhaka (n 1) 707.

- ↑ Dhaka (n 1) 708.

- ↑ Dhaka (n 1) 708.

- ↑ Right to Information Act 2005 (India), ss 19(1)–19(3).

- ↑ Right to Information Act 2005 (India) s 20.

- ↑ Rajya Sabha, Third Report on the Right to Information Bill 2004 (Department-related Parliamentary Standing Committee on Personnel, Public Grievances, Law and Justice, 21 March 2005) 33 https://rajyasabha.nic.in/rsnew/Committee_site/Committee_File/ReportFile/18/18/3_2016_6_11.pdf accessed 15 October 2025.

- ↑ Rajya Sabha, Third Report on the Right to Information Bill 2004 (Department-related Parliamentary Standing Committee on Personnel, Public Grievances, Law and Justice, 21 March 2005) 33-34 https://rajyasabha.nic.in/rsnew/Committee_site/Committee_File/ReportFile/18/18/3_2016_6_11.pdf accessed 15 October 2025

- ↑ Rajya Sabha, Third Report on the Right to Information Bill 2004 (Department-related Parliamentary Standing Committee on Personnel, Public Grievances, Law and Justice, 21 March 2005) 35 https://rajyasabha.nic.in/rsnew/Committee_site/Committee_File/ReportFile/18/18/3_2016_6_11.pdf accessed 15 October 2025.

- ↑ Rajya Sabha, Third Report on the Right to Information Bill 2004 (Department-related Parliamentary Standing Committee on Personnel, Public Grievances, Law and Justice, 21 March 2005) 35-36 https://rajyasabha.nic.in/rsnew/Committee_site/Committee_File/ReportFile/18/18/3_2016_6_11.pdf accessed 15 October 2025.

- ↑ Rajya Sabha, Third Report on the Right to Information Bill 2004 (Department-related Parliamentary Standing Committee on Personnel, Public Grievances, Law and Justice, 21 March 2005) 40 https://rajyasabha.nic.in/rsnew/Committee_site/Committee_File/ReportFile/18/18/3_2016_6_11.pdf accessed 15 October 2025.

- ↑ Government of India, Department-related Parliamentary Standing Committee on Personnel, Public Grievances, Law and Justice, Seventy-Ninth Report on Implementation of the Right to Information Act, 2005 (Rajya Sabha Secretariat, March 2016) 11 https://rajyasabha.nic.in/rsnew/Committee_site/Committee_File/ReportFile/18/18/3_2016/6_11.pdf accessed 14 October 2025.

- ↑ Government of India, Department-related Parliamentary Standing Committee on Personnel, Public Grievances, Law and Justice, Seventy-Ninth Report on Implementation of the Right to Information Act, 2005 (Rajya Sabha Secretariat, March 2016) 11 https://rajyasabha.nic.in/rsnew/Committee_site/Committee_File/ReportFile/18/18/3_2016/6_11.pdf accessed 14 October 2025.

- ↑ Government of India, Department-related Parliamentary Standing Committee on Personnel, Public Grievances, Law and Justice, Seventy-Ninth Report on Implementation of the Right to Information Act, 2005 (Rajya Sabha Secretariat, March 2016) 10 https://rajyasabha.nic.in/rsnew/Committee_site/Committee_File/ReportFile/18/18/3_2016/6_11.pdf accessed 14 October 2025.

- ↑ Government of India, Department-related Parliamentary Standing Committee on Personnel, Public Grievances, Law and Justice, Seventy-Ninth Report on Implementation of the Right to Information Act, 2005 (Rajya Sabha Secretariat, March 2016) 10 https://rajyasabha.nic.in/rsnew/Committee_site/Committee_File/ReportFile/18/18/3_2016/6_11.pdf accessed 14 October 2025.

- ↑ Government of India, Department-related Parliamentary Standing Committee on Personnel, Public Grievances, Law and Justice, Seventy-Ninth Report on Implementation of the Right to Information Act, 2005 (Rajya Sabha Secretariat, March 2016) 10-11 https://rajyasabha.nic.in/rsnew/Committee_site/Committee_File/ReportFile/18/18/3_2016/6_11.pdf accessed 14 October 2025.

- ↑ Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative. (April 2005). Submission Regarding the Recommendations of the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Personnel, Public Grievances, Law and Justice on the Right to Information Bill, 2004. Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative. Available at: https://www.humanrightsinitiative.org/programs/ai/rti/india/national/submission_cabinet_post_parl_comm_rep.pdf

- ↑ Anjali Bhardwaj and others v Union of India and others Writ Petition (Civil) No 436 of 2018, Supreme Court of India, judgment dated 15 February 2019, para 24.

- ↑ Union of India vs. Namit Sharma [(2013) 10 SCC 359]

- ↑ Satark Nagrik Sangathan, Report Card of Information Commissions in India, 2023-24 (January 2025) https://images.assettype.com/downtoearth/2025-10-14/ee1jh0k5/RC2024.pdf accessed 16 October 2025.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Satark Nagrik Sangathan, Report Card of Information Commissions in India, 2023-24 (January 2025) https://images.assettype.com/downtoearth/2025-10-14/ee1jh0k5/RC2024.pdf accessed 16 October 2025.

- ↑ Anjali Bhardwaj and others v Union of India and others Writ Petition (Civil) No 436 of 2018, Supreme Court of India, judgment dated 15 February 2019.

- ↑ Information Commissioner’s Office (2022) New UK Information Commissioner begins term,(Online) The Information Commissioner’s Office. Available at New UK Information Commissioner begins term | ICO [Accessed 2nd June 2024]

- ↑ GOV.UK (2024), Information Commisioner’s Office (Online) The GOV.UK. Available at Information Commissioner's Office - GOV.UK (www.gov.uk) [Accessed 2nd June 2024]

- ↑ Data Protection Act 2018; UK General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR); Freedom of Information Act 2000; ICO, ‘What We Do’ https://ico.org.uk/about-the-ico/what-we-do/ accessed 9 October 2025.

- ↑ Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO), ‘About the ICO’ https://ico.org.uk/about-the-ico/who-we-are/ accessed 9 October 2025.

- ↑ Data Protection Act 2018, s 119; ICO, ‘Annual Report and Financial Statements 2022’ https://ico.org.uk/about-the-ico/our-information/annual-reports/ accessed 9 October 2025.

- ↑ Office of Information Plolicy, 2020. Department of Justice Guide to the Freedom of Information Act (Online) Office of Information Policy, 2020. Available at: Office of Information Policy | Department of Justice Guide to the Freedom of Information Act [Accessed 2nd June 2024]

- ↑ Freedom of Information Act 5 USC § 552(a)(6)(A) (2018).

- ↑ FOIA 5 USC § 552(a)(4)(B).

- ↑ US Department of Justice, Office of Information Policy, ‘Department of Justice Guide to the Freedom of Information Act 2023’ https://www.justice.gov/oip/doj-guide-freedom-information-act-0 accessed 9 October 2025.

- ↑ Electronic Freedom of Information Act Amendments of 1996, Pub L No 104-231, 110 Stat 3048 (codified at 5 USC § 552(a)(2)).

- ↑ Department of the Air Force v Rose, 425 US 352, 360–361 (1976).

- ↑ Australian Government, Office of the Australian Information Commissioner, 2024. About the OAIC.(Online) Australian Government, Office of the Australian Information Commissioner, 2024 Available at About the OAIC | OAIC [Accessed 4th June 2024]

- ↑ Australian Government, Office of the Australian Information Commissioner, 2024. What we do.(Online) Australian Government, Office of the Australian Information Commissioner, 2024 Available at What we do | OAIC [Accessed 4th June 2024]

- ↑ Australian Information Commissioner Act 2010 (Cth) ss 6, 14; Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC), ‘About the OAIC’ https://www.oaic.gov.au/about-the-oaic/ accessed 9 October 2025.

- ↑ Freedom of Information Act 1982 (Cth) ss 8, 55A–55K; Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC), ‘FOI Guidelines and Resources’ https://www.oaic.gov.au/freedom-of-information/guidance-and-advice/ accessed 9 October 2025.

- ↑ Privacy Act 1988 (Cth) Part V; OAIC, ‘Privacy Complaints’ https://www.oaic.gov.au/privacy/privacy-complaints/ accessed 9 October 2025.

- ↑ Australian Information Commissioner Act 2010 (Cth) ss 6, 14; Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC), ‘About the OAIC’ https://www.oaic.gov.au/about-the-oaic/ accessed 9 October 2025.

- ↑ Information Commissoner of Canada,2024. About US(Online) Information Commisioner of Canada, 2024 Available at About us (oic-ci.gc.ca) [Accessed 5th June 2024]

- ↑ Access to Information Act RSC 1985 c A-1, s 54; Office of the Information Commissioner of Canada, ‘Our Mandate’ https://www.oic-ci.gc.ca/en/about/our-mandate accessed 9 October 2025.

- ↑ Access to Information Act RSC 1985 c A-1, ss 30–42, 41; Office of the Information Commissioner of Canada, ‘How We Investigate’ https://www.oic-ci.gc.ca/en/investigations/how-we-investigate accessed 9 October 2025.

- ↑ Access to Information Act RSC 1985 c A-1, s 38; Office of the Information Commissioner of Canada, ‘Reports to Parliament’ https://www.oic-ci.gc.ca/en/reports-parliament accessed 9 October 2025.

- ↑ Access to Information Act RSC 1985 c A-1, ss 30–42, 41; Office of the Information Commissioner of Canada, ‘How We Investigate’ https://www.oic-ci.gc.ca/en/investigations/how-we-investigate accessed 9 October 2025.

- ↑ Satark Nagrik Sangathan, Report Card of Information Commissions in India 2023–24 (Society for Citizens Vigilance Initiative, January 2025) https://www.snsindia.org accessed 14 October 2025.

- ↑ State of Uttar Pradesh v Raj Narain (1975) 4 SCC 428 (Supreme Court of India).

- ↑ S P Gupta v Union of India 1981 Supp SCC 87 (Supreme Court of India).

- ↑ Right to Information (Amendment) Act 2019 and Right to Information Rules 2019 (Department of Personnel and Training, Government of India) https://documents.doptcirculars.nic.in/D2/D02rti/RTI_Rules_2019r4jr6.pdf accessed 14 October 2025.

- ↑ Satark Nagrik Sangathan, Report Card of Information Commissions in India 2023–24 (Society for Citizens Vigilance Initiative, January 2025) 6–7 https://www.snsindia.org+accessed+14+October+2025 .

- ↑ Satark Nagrik Sangathan, Report Card of Information Commissions in India 2023–24 (Society for Citizens Vigilance Initiative, January 2025) 8–9 https://www.snsindia.org accessed 14 October 2025.

- ↑ Satark Nagrik Sangathan, Report Card of Information Commissions in India 2023–24 (Society for Citizens Vigilance Initiative, January 2025) 10 https://www.snsindia.org accessed 14 October 2025.

- ↑ Union of India v Namit Sharma (2013) 10 SCC 359 (SC) [32].

- ↑ Bhardwaj, A., Johri, A., Talukdar, I., Dewedi, A., Kumar, A., Kriplani, B., & Vahal, T. (2019). Adjudicating the RTI Act: Analysis of orders of the Central Information Commission. Satark Nagrik Sangathan (SNS) & Centre for Equity Studies (CES). available at: https://snsindia.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Adjudicating-the-RTI-Act-FINAL.pdf

- ↑ Singh, S., Bhardwaj, A., & Johri, A. (2017). Adjudicating the RTI Act (2nd ed.). Research, Assessment, and Analysis Group (RaaG) & National Campaign for People’s Right to Information (NCPRI). Available at: https://snsindia.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Adjudicating-the-RTI-Act-2nd-edition-2017.pdf

- ↑ Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative, Information Commissions and the Use of RTI Laws in India: Rapid Study 2.0 (July 2014) https://humanrightsinitiative.org/publications/rti/ICs-RapidCompStudy-finalreport-NDelhi-ATITeam-Jul14.pdf accessed 16 October 2025.

- ↑ Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative, Information Commissions and the Use of RTI Laws in India: Rapid Study 2.0 (July 2014) https://humanrightsinitiative.org/publications/rti/ICs-RapidCompStudy-finalreport-NDelhi-ATITeam-Jul14.pdf accessed 16 October 2025.

- ↑ Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative, Information Commissions and the Use of RTI Laws in India: Rapid Study 2.0 (July 2014) https://humanrightsinitiative.org/publications/rti/ICs-RapidCompStudy-finalreport-NDelhi-ATITeam-Jul14.pdf accessed 16 October 2025.