Inherent power of supreme court

The term ‘Inherent Power of the Supreme Court’ refers to the powers that the Court possesses by virtue of its status as a court of record and guardian of the Constitution. The Supreme Court has described these powers as a separate and independent basis of jurisdiction, a form of residual power that the Court may invoke whenever it is just and equitable to do so[1]. There are no explicit limitations on the types of causes or situations in which this power can be exercised, and its use is left entirely to the discretion of the Supreme Court, provided it does not violate express statutory provisions, especially those that deal specifically with the subject matter in question.

As observed in the S. Nagaraj case, justice is a virtue that transcends all barriers. Neither procedural rules nor technicalities of law can be allowed to obstruct its course[2]. This broad understanding of "justice" empowers the Court to exercise its authority under Article 142 to do "complete justice" in a wide range of cases, each decided based on its unique facts and circumstances[3].

Official Definition of Inherent Powers of Supreme Court

There is no statutory definition of “inherent powers,” but the Court possesses wide-ranging powers of judicial review, granting it sweeping jurisdiction and correspondingly broad authority to do complete justice. This power is conferred by Article 142 of the Indian Constitution. It provides Enforcement of decrees and orders of the Supreme Court and orders as to discovery. The Supreme Court can pass any order or decree needed to ensure complete justice in a case before it. These orders can be enforced throughout India as per laws made by Parliament or, until such laws are made, as directed by the President.The Supreme Court can issue orders across India to make people attend court, produce documents, or to deal with contempt of court, subject to any law made by Parliament.

Inherent power of SC as defined in international instrument

UN Basic Principles on the Independence of the Judiciary (1985)

The UN Basic Principles on the Independence of the Judiciary (1985) implicitly support the concept by affirming the essential, non-codified powers necessary for the effective functioning of courts. Adopted on 6 September 1985 at the Seventh United Nations Congress on the Prevention of Crime and the Treatment of Offenders in Milan, these principles emphasize that the independence of the judiciary must be guaranteed by the State and reflected in constitutional or legal frameworks. Key provisions uphold that the judiciary must act impartially and without interference (Principles 1–4), have full jurisdiction over judicial matters (Principle 3), and ensure fair trials (Principles 5–6). These principles indirectly affirm that courts, by virtue of their independence and constitutional role, must possess certain inherent powers to uphold justice effectively, even if such powers are not codified. Additionally, Member States are obligated to provide adequate resources (Principle 7) to ensure the judiciary can fulfill its duties, further supporting the structural autonomy needed to exercise such powers.

Inherent power of SC as defined in official document

Constituent Assembly Debates

Article 142, initially numbered as Draft Article 118, was presented to the Constituent Assembly on May 27, 1949, and adopted the same day without debate. This suggests a consensus that the Supreme Court should have broad powers to ensure justice. The Constituent Assembly debate on Article 118 (now Article 142) highlighted the need to give the Supreme Court strong powers to do complete justice. While citizens were given fundamental rights and the right to approach the Supreme Court, there was no clear process on how the Court would enforce these rights. Members argued that the Court must have wide powers, not just in appeals, but in any matter where justice is needed. Article 118 was seen as a powerful tool that allowed the Court to go beyond technical rules and take up cases even outside regular court areas like revenue or tribunals. The Court was expected to act based on fairness and natural justice, even if no formal law or procedure allowed it. The debate showed a clear intent to give the Supreme Court the freedom to ensure justice, without being blocked by legal or procedural hurdles[4].

14th Law Commission of India Report

The14th Law Commission of India Report titled 'Reform of Judicial Administration' it is stated that the courts, including the Supreme Court, possess inherent powers to ensure justice in situations not expressly covered by law, emphasizing that such powers are essential to prevent injustice or abuse of the legal process, even when the law is silent.

“The Supreme Court often formulates and reformulates the concept of inherent powers. The Supreme Court has tried to streamline the contours of the inherent powers. It cannot be said to be an attempt at structuring the inherent powers. The Supreme Court's decisions at time appear to be prescribing the permissible and impermissible limits of inherent powers. With imperceptibly minor variations, the Supreme Court goes on expounding the inherent powers. The roots of inherent powers are traced to, equity[5].”

Inherent power of SC as defined in Case Laws

The scope of Article 142 has been expanded to the extent that it virtually allows judges to use it as a carte blanche to disregard existing statutory provisions and constitutional restrictions while exercising their powers under this Article[6]. The jurisdiction and powers of the Supreme Court under Article 142 are supplementary in nature and are intended to ensure complete justice in any matter. These powers are independent of the Court’s jurisdiction under Article 129 and cannot be restricted by any statutory provision, including those in the Advocates Act or the Contempt of Courts Act[7]. Courts have cautioned against the use of Article 142 to supplant rather than supplement substantive law[8]. In several cases, the Supreme Court has invoked Article 142 to issue directions in public interest[9], even when statutory provisions were already in place, raising concerns about inconsistency. The Court has adopted both liberal and restrained interpretations, at times using the provision to bypass procedural technicalities, and at other times limiting its application to situations where a legislative vacuum exists.

The Court has also exercised Article 142 to lay down binding guidelines[10] in the absence of existing laws, reinforcing its role in maintaining governance continuity until appropriate legislation is enacted. Overall, while Article 142 endows the Supreme Court with extraordinary powers, its exercise must remain anchored in constitutional values, statutory limits, and the principles of natural justice[11].

Supreme Court Bar Association v. Union of India (1998)

In the landmark case of Supreme Court Bar Association v. Union of India[12], the Supreme Court clarified that Article 142 cannot be used to override or replace existing laws. The Court made it clear that this Article cannot be used to indirectly achieve what is not allowed directly under the law. It explained that while the powers under Article 142 are meant to complement existing legal provisions, they cannot be used to create new rules or ignore clear statutory provisions. This case helped define the limits of the Supreme Court’s powers under Article 142, and its interpretation continues to be followed today.

In K.M. Nanavati v. State of Bombay[13], a five-judge bench considered the scope of Article 142 in relation to the governor’s power to grant pardons and suspend sentences under Article 161. To ensure both provisions worked together, the Court held that the governor’s power to suspend a sentence could not be used while the case was still pending before the Supreme Court under Article 142. Legal scholars have observed that the Court took a broad and unrestricted view of Article 142 in this case.

High Court Bar Association, Allahabad v. State of U.P (2024)

In High Court Bar Association, Allahabad v. State of U.P[14], the Supreme Court reiterated important limits by stating that It is difficult to lay down an exhaustive list of parameters governing the exercise of powers under Article 142 of the Indian Constitution, due to the exceptional nature of these powers. However, certain key principles have emerged:

- Complete Justice Between Parties: The jurisdiction under Article 142 can be exercised to do complete justice between the parties before the Court, but it cannot be used to undo benefits granted to non-parties through valid judicial orders.

- Respect for Substantive Rights: Article 142 does not empower the Court to override the substantive rights of litigants.

- Procedural Flexibility, Not Substantive Overreach: The Court may issue procedural directions to ensure smoother and faster case disposal. While procedural laws may be relaxed, substantive rights of non-parties cannot be compromised. The right to be heard is not merely procedural but a substantive right.

- Adherence to Natural Justice: The power under Article 142 must not be exercised in violation of the principles of natural justice, which are foundational to Indian jurisprudence.

Shilpa Shailesh v. Varun Sreenivasan (2023)

In Shilpa Shailesh v. Varun Sreenivasan[15], the Supreme Court elaborated on the scope of its powers under Article 142 of the Constitution. The Court held that it may depart from both procedural and substantive laws if such departure serves the interest of public policy. Notably, the Court affirmed that it has the discretion to dissolve a marriage by mutual consent without requiring the parties to file a second motion when there is a clear settlement between them. Additionally, the Court can quash criminal proceedings or orders under Article 142 and may dissolve a marriage on the ground of irretrievable breakdown. These powers are to be exercised to ensure complete justice, especially where it is evident that the marriage has irreversibly failed and continuing the legal relationship would be unjustified.

International Experiences

Bangladesh

When comparing provisions related to the inherent powers of the Supreme Court, it is evident that only Bangladesh and Nepal have similar systems, and both appear to have borrowed these provisions from the Constitution of India. In Bangladesh, Article 102 of the Constitution grants the High Court Division broad constitutional authority to issue writs such as habeas corpus, mandamus, prohibition, certiorari, and quo warranto. These powers are frequently used to enforce fundamental rights and hold public authorities legally accountable. Additionally, Article 104 empowers the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court to pass any orders necessary to ensure complete justice mirroring the wide discretionary power seen under Article 142 of the Indian Constitution.

United States of America

Federal courts in the U.S. have inherent powers that are essential for carrying out their duties and ensuring justice. These powers are not specifically mentioned in the Constitution or laws but are understood to exist by the nature of the courts themselves. Since early in U.S. history, the Supreme Court has recognized that courts need these powers to function effectively. They include the ability to manage court procedures, ensure fair trials, punish contempt, and issue or cancel judgments[16].

United Kingdom

The UK Supreme Court holds certain inherent powers that allow it to ensure justice is done in complex or exceptional situations. These powers are not always written in law but are understood to exist as part of the Court’s role in upholding fairness and justice. However, the Court uses these powers carefully and only when necessary. For example, if a law allows lower courts to follow a special closed process for sensitive matters, the Supreme Court may also use a similar process when reviewing those decisions. Still, the Court prefers open and transparent proceedings and usually avoids using secret procedures unless absolutely required. Overall, the use of inherent powers in the UK is guided by principles of fairness, the need for clear laws, and the protection of individual rights[17].

Canada

Provincial and territorial superior courts in Canada have inherent jurisdiction, allowing them to address cases in any area unless a law specifically restricts their authority. These courts also have the power to fill gaps in procedure and prevent misuse of the legal process[18].

Appearance of Inherent power of SC in Database

National Judicial Data Grid

The following table presents real-time data from the National Judicial Data Grid (NJDG) on registered and disposed civil and criminal cases in the Supreme Court of India, including details such as case type, bench-wise pendency, and monthly trends.

Research that engages with inherent power of SC

The Supreme Court of India’s Use of Inherent Power under Article 142 of the Constitution: An Empirical Study (Indian Institute of Management Ahmedabad – Working Paper Series)

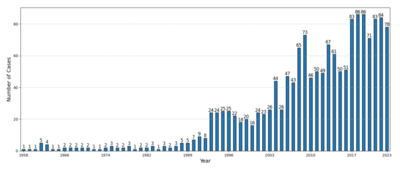

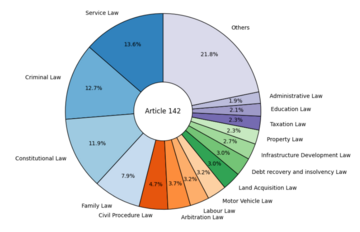

This working paper titled The Supreme Court of India’s Use of Inherent Power under Article 142 of the Constitution: An Empirical Studyby M.P. Ram Mohan, Sriram Prasad, Vijay V. Venkitesh, Sai Muralidhar, and Jacob P. Alex (revised May 2025) presents an empirical analysis of how the Supreme Court of India uses its inherent powers under Article 142 to do complete justice. The study compiles and hand-codes 1579 Supreme Court cases from 1950–2023 that mention either Article 142 or complete justice. It explores when and how these powers are invoked, across civil, criminal, and constitutional matters[19].

Figure 1 shows how the use of Article 142 and the phrase "complete justice" in Supreme Court cases has changed over the years. The data (from 1579 cases) indicates that such references were rare in earlier decades but began increasing significantly from the 1990s onward. Figure 2 displays the top 15 types of primary laws most commonly involved in these cases, highlighting the legal areas where the Court most often invoked its inherent powers.

Theory of the Inherent Powers of the Federal Courts (Catholic University Law Review)

The article Theory of the Inherent Powers of the Federal Courts authored by Benjamin H. Barton and published in 2011 examines the scope and origin of the inherent powers of federal courts in the United States. This article challenges the traditional notion that federal courts derive their inherent powers solely from Article III of the U.S. Constitution. Instead, it argues that these powers are more appropriately grounded in Article I, specifically the Necessary and Proper Clause.The author explores historical records, the Constitution’s text, ratification debates, and early case law to show that courts have broad but non-constitutional authority to manage procedures and ensure justice, authority that Congress can regulate[20].

Exercise of Inherent Power by the Supreme Court of India to Do Complete Justice with Special Reference to Divorce Matters under the Hindu Marriage Act – A Critical Analysis (Ilkogretim Online – Elementary Education Online, Vol. 20, Issue 1, 2021)

This article titled Exercise of Inherent Power by the Supreme Court of India to Do Complete Justice with Special Reference to Divorce Matters under the Hindu Marriage Act – A Critical Analysis by Sayalee S. Surjuse, critically examines the use of the Supreme Court’s inherent powers under Article 142 in the context of divorce cases under the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955. The study reviews how the Supreme Court’s use of Article 142 in divorce cases has evolved through four phases - restricted, broad, benevolent, and harmonious. It shows a shift from strict legal adherence to more justice-focused interventions, such as granting divorces by bypassing legal procedures. While aimed at doing complete justice, the article flags concerns about judicial overreach and inconsistency, concluding that until Parliament addresses irretrievable breakdown in law, the Court will continue to rely on Article 142 in exceptional cases[21].

Way Ahead

Article 142 is used by the Supreme Court in rare and exceptional situations to ensure complete justice. Since these situations are unique, finding a single pattern behind its use is difficult. However, certain trends have emerged such as using Article 142 to grant divorces[22], resolve commercial disputes, fill legal gaps, or go beyond existing laws and procedures. The Court’s decision to invoke this Article may also depend on the case type, legal issue, judges involved, or relevant statutes. Often, the Court states that such cases should not be treated as precedents, which leads to confusion due to inconsistent application.

Use of different Nomenclature across regions on Inherent power of SC

Terms like “plenary powers,” “extraordinary jurisdiction,” or “judicial discretion” are used in lieu of “inherent powers” depending on context. Parens Patriae is used in public interest litigation (PIL) contexts.

References

- ↑ Ajit Sharma, Inherent Powers of the Supreme Court under the Constitution, (2006) PL June 12, available at: https://www.ebc-india.com/lawyer/articles/2006_pl_6_2.htm

- ↑ S. Nagaraj v. State of Karnataka, 1993 Supp (4) SCC 595

- ↑ M.P. Jain: Indian Constitutional Law, (5th Edn. Vol. I) p. 306.

- ↑ Constituent Assembly Debates, vol. 8 (May 16–June 16, 1949), https://www.constitutionofindia.net/constituent-assembly-debate/volume-8/.

- ↑ Law Commission of India, 14th Report,P. 828

- ↑ Union Carbide Corporation vs Union Of India Etc, 1990 AIR 273

- ↑ Re: Vinay Chandra Mishra, AIR1995SC2348

- ↑ Rajat Pradhan, ‘Ironing out the Creases: Re-Examining the Contours of Invoking Article 142(1) of the Constitution’ (2011) 6 NALSAR Stud. L. Rev 1, https://www.commonlii.org/in/journals/NALSARStuLawRw/2011/1.pdf

- ↑ The State Of Tamil Nadu Rep. By Sec.&Ors; vs K. Balu & Anr; Union Of India vs Ashish Agarwal

- ↑ Vishaka and Ors v State of Rajasthan and Ors, AIR 1997 SC 3011; Common Cause v Union of India, (2018) 5 SCC

- ↑ Pradhan, supra note 1

- ↑ AIR 1998 SUPREME COURT 1895

- ↑ 1962 AIR 605

- ↑ 2024 INSC 150

- ↑ 2023 INSC 468

- ↑ U.S. Const. art. III, § 1, Overview of Inherent Powers of Federal Courts, Cornell L. Sch. Legal Info. Inst., https://www.law.cornell.edu/constitution-conan/article-3/section-1/overview-of-inherent-powers-of-federal-courts

- ↑ Michael Bromby, The Privy Council Reinstates Principle Over Pragmatism: Inherent Powers and When to Use Them in Relation to Holding a Closed Material Procedure, 28 J. Jud. Rev. 270 (2023), https://doi.org/10.1080/10854681.2023.2273636.

- ↑ Canada, Dep’t of Justice, Canada’s Court System (2015), J2‑128/2015E‑PDF, https://canada.justice.gc.ca/eng/csj‑sjc/ccs‑ajc/pdf/courten.pdf.

- ↑ M.P. Ram Mohan, Sriram Prasad, Vijay V. Venkitesh, Sai Muralidhar K. & Jacob P. Alex, The Supreme Court of India's Use of Inherent Power under Article 142 of the Constitution: An Empirical Study, IIMA Working Paper Series (May 2024, rev. May 2025), https://ssrn.com/abstract=4809518

- ↑ Benjamin H. Barton, An Article I Theory of the Inherent Powers of the Federal Courts, 61 Cath. U. L. Rev. 1 (2012), https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview/vol61/iss1/1.

- ↑ Sayalee S. Surjuse, Exercise of Inherent Power by the Supreme Court of India to Do Complete Justice with Special Reference to Divorce Matters under the Hindu Marriage Act – A Critical Analysis, 20 Elementary Educ. Online 1740 (2021), https://ilkogretim-online.org/index.php/pub/article/view/3456.

- ↑ Apoorva, Supreme Court Invokes Article 142 to Dissolve Marriage on Grounds of Irretrievable Breakdown; Grants Wife Visitation Rights with Daughter, SCC Online (Apr. 28, 2025), https://www.scconline.com/blog/post/2025/04/28/supreme-court-article-142-marriage-dissolution-visitation-rights/