International Criminal Court (ICC)

What is the International Criminal Court

Establishment

The International Criminal Court (ICC) is a permanent and treaty-based international tribunal, which is located in The Hague, Netherlands. It was established in 2002 under the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, with the jurisdiction to prosecute individuals accused of the crime of genocide, crimes against humanity, crime of aggression and war crimes and is the only international tribunal that is accorded with the jurisdiction to investigate and prosecute individuals who commit atrocities against mankind[1]. The establishment of the Court can be traced back to the recognition by the international community of the need for holding perpetrators of mass atrocities accountable for their impunities and is considered to be a milestone in the development of international human rights, with the work on the draft statue of the International Criminal Court commencing on the very day prior to the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948.[2]

Historical Background

The notion of establishing an international tribunal for the trial of international crimes was first proposed at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference following World War I.[3] The idea of a permanent international tribunal for prosecuting genocide was raised on December 09, 1948 in Resolution 260 of the United Nations General Assembly, that adopted the Convention of the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, which also invited the International Law Commission to explore the feasibility of establishing an international judicial organ for the prosecution individuals charged with the crime of genocide[4]. However, in the early years of the Cold War, after two draft attempts, the consideration was postponed indefinitely due to a lack of consensus from the geopolitical tensions. Thereafter, in the aftermath of World War II, the international community once against started to coalesce on the idea of the establishment of a permanent court. In 1998, on a request by Trinidad and Tobago, the General Assembly mandated the International Law Commission (ILC) to resume their exploration of the creation of a permanent court[5]. It is subsequently that the UN Security Council established the two ad-hoc tribunals for the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda, which further highlighted the need for the establishment of a permanent court to address the structural limitations and deficiencies of these tribunals. Although the mandate of the ICC aligns with the goals of the Nuremberg and Tokyo trials as well as the establishment of the International Criminal Tribunals for the former Yugoslavia and for Rwanda, the ICC is not bound by a specific time frame or a specific instance and was borne out of an international consensus for the establishment of an international and permanent body.

Soon after, the ILC completed its draft statute for the established of an international criminal court, which was submitted in 1994. After due consideration by the General Assembly, through an Ad-Hoc Committee on the Establishment of an International Criminal Court. The Statute of the International Criminal Court (Rome Statute) was adopted in Rome on July 17, 1998 as the birthchild of the United Nations Diplomatic Conference of Plenipotentiaries on the Establishment of an International Criminal Court organised by the United Nations (UN)[6]. In addition to the Rome Statute, the Conference also adopted a Final Act – providing for the establishment of a Preparatory Commission by the United Nations General Assembly for preparing a consolidated draft text including the Rules & Procedures and other specific agreements relating to the establishment and administrative elements of the Court. The Statute came into force on July 01, 2002 and commenced its sitting after ratification by 60 States.

In 2018, with the celebration of two decades of operation of the Court, the stakeholders reflected on the systemic working of the ICC and launched a review of the system of the Court and the Rome Statute in order to address concerns such as low conviction rates, lack of cooperation of states, etc[7]. The 18th Session of the Assembly of State Parties adopted a resolution that mandated a group of independent experts to carry out an Independent Expert Review (IER) and formulate recommendations for consideration[8]. In 2020, the experts released a final report an analysis of the working of the Court coupled with recommendations to alter the system[9]. Following 2021, an ICC Review Mechanism was put in place to ensure a timely follow up on the assessment and implementation of the recommendations[10].

Members of the Court

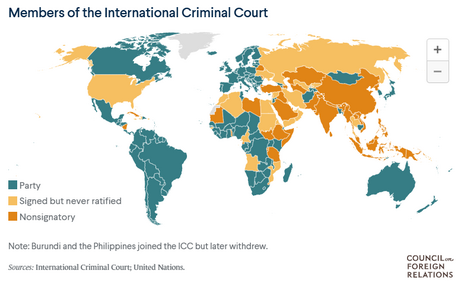

125 countries are States Parties to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. Out of them 33 are African States, 19 are Asia-Pacific States, 20 are from Eastern Europe, 28 are from Latin American and Caribbean States, and 25 are from Western European and other States. Approximately around 40 countries such as China, India, Indonesia, North Korea, etc never signed the statute. Several other countries signed the statute, but their legislatures did not ratify the same, including the United States, Russia, Israel, etc. Two countries withdrew from the Statute - with Burundi leaving in 2017 when the Court initiated an investigation against the governments actions regarding opposition protests and Philippines leaving in 2019, citing international interference into domestic affairs when the Court conducted an inquiry into the governments war on drugs[11].

How does the ICC work?

The Assembly of State Parties

The Assembly of State Parties[12] consists of the group of state parties who have ratified the Statute and is a member of the Court. Article 112 of the Statute provides for the establishment of the Assembly of State Parties, where each state party has one representative.[13] The ASP is responsible for the oversight of the Presidency, the Prosecutor and the Registrar for the smooth functioning of the Court. The Assembly is also responsible for the election of the Judges and Prosecutor of the Court. It is mandated with adoption of appropriate recommendations by the Preparatory Committee as well as deciding the budget of the Court.

Organs of the ICC

Article 34 of the Rome Statute[14] provides for the following organs:

The Presidency

The Presidency, as mentioned in Article 38 of the Rome Statute[15], consists of the President and the First & Second Vice Presidents who are elected through an absolute majority vote amongst the 18 judges, for a term of three years (renewable) and are responsible for the supervision of the administration of the Court (with the exemption of the Office of the Prosecutor) in three main areas – judicial functions, administration and external relations. In pursuance of this mandate, the Presidency is responsible for the assignment of cases, judicial review of Registry decisions as well as cooperation agreements with States.

The Judicial Divisions

Under Article 39, Rome Statute[16], the ICC’s Judicial Divisions consists of 18 Judges who are elected by the Assembly of States Parties for a term of 9 years (non-renewable). Their functions revolve around the judicial functions that span from conducting fair trials and decisions to the issuance of warrants or summonses, etc. There are three Chambers to which the judges are assigned which is differentiated based on the stage of trial – Pre-Trial Judges, Trial Judges and Appeals Judges – who handle the respective stages of the trial.

The Office of the Prosecutor

The Office of the Prosecutor or the OTP, under Article 42 of the Rome Statute[17], is an independent organ of the ICC which is accorded the responsibility of examining conflicts coming under the jurisdiction of the Court and conducting the investigation and prosecution of the perpetrators. The OTP consists of the Prosecutor and Deputy Prosecutors who are elected by the Assembly of State Parties for a term of 9 years (non-renewable).

The Registry

The Registry, as mentioned in Article 43 of the Rome Statute[18], is the organ of the Court that provides the administrative services to the other organs of the ICC and acts as a neutral facilitator for the conduct of fair judicial proceedings and is responsible for providing – judicial support, external affairs and management. In pursuance of the same, the Registry is responsible for general court management and court records, public information, outreach, victims and witness support as well overall management including security, finance, human service and other general services. The Registry is headed by the Registrar & Deputy Registrar, elected by absolute majority vote by the judges for a term of 5 years.

| Organ | Function | Composition | Term |

| The Presidency | Proper administration of the Court (except the Office of the Prosecutor) | Consists of the President and the First & Second Vice Presidents | 3 Years (renewable) |

| The Judicial Divisions | Carries out judicial functions | Elected 18 judges are assigned to the Appeals Division, Trial Division and Pre-Trial Division | 9 years (non-renewable) |

| The Office of the Prosecutor | Receipt of referrals, examination of information and conducting investigations and prosecutions before the Court | Headed by the Prosecutor and assisted by Deputy Prosecutors | 9 years (non-renewable) |

| The Registry | Non-judicial aspects of administration and servicing of the Court | Headed by the Registrar and assisted by Deputy Registrar | 5 years (renewable) |

What is the jurisdictional scope of the ICC?

Article 5 of the Statute

Article 5 of the Rome Statute[19] states that the jurisdiction of the Court is limited to ‘serious crimes of concern to the international community as a whole’ and is restricted to the adjudication of matters with respect to the following crimes:

- The crime of genocide: Defined under Article 6 of the Statute[20], the definition is the same as that used in the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, 1948.

- Crimes against humanity: Defined under Article 7 of the Statute by a non-exhaustive list of acts that constitute the same including murder, rape, slavery and other similar violations committed as part of a massive attack against a civilian population.[21]

- War Crimes: Defined under Article 8 of the Statute and includes violations of the law of war under the Geneva Conventions and under customary international law such as torture, intentional attacks on civilian populations, etc.[22] Article 124 of the Statute is a corresponding transitional provision that declares that a state may choose to exempt itself from the jurisdiction under Article 8 for a period of 7 years after ratification.[23]

- The crime of aggression: Defined under Article 8 bis[24] to include instances where a person in a position of authority exercises control by directing the political or military actions to compromise the sovereignty, territorial integrity or political independence of another nation or in a manner violating the United Nations Charter.

Territorial, Personal & Temporal Jurisdiction

The jurisdiction of the Court covers all individuals who commit the above-mentioned crimes regardless of their location as long as the twin conditions of them being nationals of either State Parties to the Statute or of states who have deemed to accept the jurisdiction of the Court[25]. The ICC possesses the jurisdiction to try natural persons who are accused of the above crimes and has the power to hold individual criminally responsible, although the Court has no jurisdiction over individuals who were minors at the time of the alleged commission[26]. The ICC also only has jurisdiction over crimes committed after the Statute entered into force for the state concerned which is in line with the principle of non-retroactivity for criminal laws[27].

The Working of the Court

The ICC can formally open an investigation into the instance where an alleged crime has taken place through three ways:

- The matter is formally referred to the Office of the Prosecutor by a member country of the commission of the crime(s) arising anywhere in the world[28] or;

- The matter is referred to the Prosecutor by the UN Security Council acting under Chapter VII of the Charter of the United Nations or;

- The Prosecutor launches an investigation proprio motu, with the approval of the Pre-Trial ICC Chamber Judges.[29]

In case of a situation where the Prosecutor has decided to take proprio motu action, then a preliminary examination of the situation is conducted, based on which a request is formally submitted to the Pre-Trial Chamber to authorize a formal investigation. In case, a State Party submits a referral, then the referral is examined under the requirement of the Rome Statute, and if such criterion are fulfilled, then an investigation is launched by the Prosecutor to determine the responsible individuals.[30]

In case the matter calls for investigating individuals from non-party states for committing offences in a State Party’s territory, then the same can be carried out if either the non-member party deems to accept the jurisdiction of the Court or with the authorisation of the UN Security Council.

Once the initial preliminary examination is completed, the Prosecutor arrives at a conclusion as to whether the alleged crimes are of sufficient gravity to open a formal investigation. If concluded that an investigation is formally warranted, then the Office of the Prosecutor sends out investigators and staff members for collection of evidence[31]. In case of issuance of warrants or summons, the same is to be approved by the Judges[32]. In case of apprehending the accused, the cooperation of State Parties is paramount as the ICC does not have a force of its own. However, all State Parties are obliged to arrest any individual within their territory against whom an arrest warrant has been issued by the ICC[33]. Thereafter, it is brought to the Pre-Trial Chamber judges for confirmation as to whether the case should be brought to trial before the Trial Chamber judges[34]. Any final conviction or sentences doled out require a majority vote amongst the three judges on a trial bench. The judgement can be appealed to at the Appellate Chamber of the ICC which is made up of 5 judges.

Requirements for Initiation of Investigation

In order to formally initiate an investigation, the Prosecutor must take into consideration the following aspects[35]:

- Firstly, if the information available constitutes a reasonable basis towards the belief of commission of the crime

- Secondly whether, the issues of admissibility covered under Article 17 prevent the same from being admitted.[36] The Statute prohibits admission in cases where the case has or is being investigated or prosecuted by a State which has jurisdiction over the matter or the matter does not possess sufficient gravity or in case the subject matter has already tried (ne bis in idem), as the Statute prohibits double jeopardy.

- Thirdly, whether the investigation would serve the interests of justice while taking into consideration the gravity of the crime as well as the interests of the victim.

In case the matter is already being or has been investigated or prosecuted by a State which has jurisdiction over the matter, then the Court can only consider the same in case the State is genuinely unable to do the same or is unwilling. The element of unwillingness is to be considered by the Court with regard to the principles of due process in international law if:

- The purpose behind institution of proceedings were to shield the perpetrator(s) from criminal responsibility

- There is inconsistency in the intent to dole out justice by way of an unjustified delay in institution of the proceedings

- The nature of the proceedings are not independent or impartial which is inconsistent with the intent to bring the perpetrator to justice.

If the Prosecutor concludes that there is no sufficient basis for a prosecution then, the same is communicated to the Pre-Trial Chamber. The determination of the Prosecutor can be reviewed by the Pre-Trial Chamber either at the request of the State Party or UN Security Council or of its own initiative. However, in case any new facts or information comes to light then, the Prosecutor may at any time reconsider the decision.

Pre-Trial Chamber

The role of the Pre-Trial Chamber can be traced to the investigation stage where if the Prosecutor is of conclusion that there is a unique opportunity at hand to obtain testimony from a witness or to collect evidence, then the Chamber is to be informed. In such a case the Chamber, while taking necessary steps to protect the rights of the defence, may take any such action as may be necessary to collect or preserve the evidence. The Pre-Trial Chamber is accorded with the power to issue orders and warrants as may be required at any time after the initiation of the investigation, if it is satisfied that such an action is warranted. Any State Party that has received the request for arrest and surrender shall immediately take the necessary steps to apprehend the person. Once ordered to be surrendered, the person shall be delivered to the Court as soon as possible.

The Pre-Trial Chamber shall ensure that the person has been informed of the alleged crimes. The Statute states that after the persons surrender/voluntary appearance before Court, the Court shall hold a hearing for the confirmation of charges on which the Prosecutor intends to seek for trial within a reasonable period.

The hearing will be held in the absence of the individual in case the person has either waived their right to be present or cannot be found despite reasonable measures taken to locate the person. In such case then, the person shall be represented by counsel if the Chamber deems it to be in the interests of justice.

Prior to initiation of the hearing, the person is to be furnished with the document detailing the charges mounted against them and informed of the evidence being relied on. The investigation may continue till before the hearing, and the charges may be amended or withdrawn in case of any new changes.

At the hearing for the confirmation of the charges, the Prosecutor is to substantiate each charge brought against the person with sufficient evidence to establish grounds for belief that the person committed the crime charged with. Such person may in response either object, challenge the evidence presented or present new evidence of their own.

It is on the basis of this hearing that the Pre-Trial Chamber is to determine whether the evidence is sufficient to establish substantial grounds for belief. On the basis of its determination, the Pre-Trial Chamber may:

- Confirm the charges and commit the person to a Trial Chamber for trial on the confirmed charges or;

- Decline to confirm the charges in case of insufficient evidence or;

- Adjourn the hearing in order to request the Prosecutor to either provide further evidence and/or conduct further investigation or amend a charge because the evidence submitted establishes a different crime.

In a matter where the charges have been confirmed, the Presidency shall then constitute a Trial Chamber, mandated with the responsibility of conducting the subsequent trial and proceedings.

Trial Chamber

The Trial Chamber is responsible for conducting a fair and expeditious trial that respects the right of the accused as well as accords due regard towards the protection of the victim(s) and the witnesses. The trial is held publicly in normal circumstances, unless there are special reasons for the proceedings to be conducted in closed session such as the nature of the crime – where it involves sexual or gender violence or violence against children - or to protect confidential information.

During the commencement of the trial, the Trial Chamber shall read the charges previously confirmed to the accused and satisfy itself that the accused is aware of the nature of the charges. The accused is then granted the opportunity to either make an admission of guilt or to plead not guilty[37]. If the accused makes an admission of guilt, the Trial Chamber is to ensure that the admission is voluntary, informed and supported by the charges, materials and evidence brought forward by the Prosecutor. If the same is established, then the Trial Chamber may consider the admission of guilt with any additional evidence presented and may convict the accused. However, if the Chamber is not satisfied then it shall consider the admission as not having been made and order that the trial continue under normal circumstances and may remit the case to another Trial Chamber[38].

The Trial Chamber shall hear the testimonies of the witnesses in person and in accordance with the Rules of Procedure and Evidence and the Chamber shall rule on the relevance or admissibility of the evidence by taking into account the probative value of the evidence and any prejudice such evidence may cause to the conduct of a fair trial.

In order to render a decision, Article 74 of the Statute lays down certain requirements to be adhered to:[39]

- All the judges of the Trial Chamber is to present at every stage of the trial and through deliberations.

- The final decision shall be based on the evaluation of the evidence and the entire proceedings and shall not exceed the facts and circumstances in the charges.

- The judges must strive for unanimity but in case of division, then the decision of the majority of the judges will be considered.

- The deliberations are to remain secret.

- The final decision of the Trial Chamber shall be a detailed and reasoned statement of its findings on the evidence and conclusions which is to be delivered in open court. The Chamber is to issue one decision, however in case of no unanimous decision, the views of both the majority as well as the minority are to be included.

In case of a conviction, the Trial Chamber is to consider an appropriate sentence to be imposed on the basis of the proceedings conducted and is to be pronounced in public, if possible, in the presence of the accused person. Article 77 of the Statute provides for applicable penalties, and the Chamber may impose the following sentences:[40]

- Imprisonment for a specified number of years (a maximum of 30 years) or;

- Life imprisonment (justified by the gravity of the crime and the circumstance of the convict)

- A fine (provided for in the Rules of Procedure and Evidence)

- A forfeiture of proceeds, property and assets derived indirectly or directly from the commission of the crime

Appeal & Revision

The decision of the Trial Chamber may be appealed against in accordance with the Rules of Procedure and Evidence by either the Prosecutor or the convicted person – based on either a procedural error, error of fact, error of law or any other ground that affects the fairness of the proceedings[41]. A sentence may be appealed only with regards to disproportionality between the crime and the sentence imposed.

For the appellate proceedings, the Appeals Chamber is accorded all the powers of the Trial Chamber. If the Appeals Chamber is of the opinion that the proceeded appealed from were affected by any of the grounds for appeal it may either:

- Reverse or amend the decision/sentence or;

- Order for a new trial before a different Trial Chamber[42]

The judgement of the Appeals Chamber shall be through the decision rendered by the majority of the judges and is to be delivered in open court. The judgement shall contain the reasons on which the same is based and in case of a divided opinion, it shall contain the views of both majority as well as the minority.

Similarly, the convicted person or any person authorised by the convict may apply to the Appeals Chamber for revision of the final judgement of conviction or sentence based on the following grounds:

- In case of discovery of new evidence which was not available at the time of trial or;

- If any decisive evidence taken into account at trial was false, forged or falsified or;

- Any of the judges involved in conviction or confirmation of charges has committed any serious misconduct that justifies removal of the judge(s).

If the Appeals Chamber deems the application to be meritorious it may reconvene the original Chamber or constitute a new one or retain their jurisdiction over the matter.

Investigations & Trial History

Investigations

The Office of the Prosecutor initiates investigations upon referral by State Parties, the UNSC or of its own volition and performs the same by gathering relevant evidence and testimony from victims and witnesses in order to substantiate reasonable grounds for belief of commission of the alleged crime.

Investigations by the ICC

The Investigations underway at the ICC are available on the official website. The same can be accessed under Situations and Cases on the official website.

History of Investigations

The following is a compilation of the history of situations investigated by the ICC:

| Country of Conflict | Status | Referral | Investigation Initated | Situation in Focus | Regional Focus |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | Ongoing | March, 2004 by the DRC Govt. | June, 2004 | Allegations of war crimes & crimes against humanity (armed conflict in DRC since July 01, 2002) | Eastern DRC (since January 01, 2022) |

| Uganda | Concluded

(December 01, 2023) |

January, 2004 by the Govt. of Uganda | July, 2004 | Allegations of war crimes & crimes against humanity (conflict between LRA & national authorities since July 01, 2002) | Northern Uganda |

| Sudan | Ongoing | March, 2005 by the UNSC | June, 2005 | Allegations of genocide, war crimes & crimes against humanity (Darfur, Sudan since July 01, 2002) | Darfur, Sudan |

| Central African Republic (CAR) | Concluded (Dec 16, 2022) | Dec, 2004 by the CAR Govt. | May, 2007 | Allegations of war crimes & crimes against humanity (Conflict in CAR since July 01, 2002) | Throughout CAR |

| Kenya | Concluded (Nov 27, 2023) | March, 2010 by ICC Prosecutor (proprio motu) | Allegations of crimes against humanity (post-election violence in Kenya in 2007-2008) | Kenyan Provinces of Nairobi, North Rift Valley, Central Rift valley, South Rift Valley, Nyanza Province & Western Province | |

| Libya | Ongoing | Feb, 2011 by the UNSC | March, 2011 | Allegations of war crimes & crimes against humanity (situation in Libya since Feb 15, 2011) | Throughout Libya and specifically Tripoli, Benghazi & Misrata |

| Cote d’Ivoire

(accepted jurisdiction of ICC in April 2003 |

Ongoing | Oct 03, 2011 by ICC Prosecutor after Pre-Trial Chamber authorisation (proprio motu) | Allegation of crimes within the jurisdiction of the Court (post-election violence in Cote d’Ivoire in 2010/2011 and since Sep 19, 2002) | Throughout Cote d’Ivoire including Abidjan & western Cote d’Ivoire

| |

| Mali | Ongoing | July, 2012 by the Govt. of Mali | Jan, 2013 | Allegations of war crimes (situation in Mali since Jan, 2012) | Three northern regions – Gao, Kidal & Timbuktu with incidents in Bamako & Sevare (south) |

| Central African Republic (CAR) II | Concluded (Dec 16, 2022) | May, 2014 by the CAR Govt. | Sep, 2014 | Allegations of war crimes & crimes against humanity (renewed violence starting in 2012 in CAR) | Throughout CAR |

| Georgia | Concluded (Dec 16, 2022) | Jan 27, 2016 by ICC Prosecutor after Pre-Trial Chamber authorisation (proprio motu) | Allegations of war crimes & crimes against humanity (International Armed Conflict between Jul 01 and Oct 10, 2008) | South Ossetia Region | |

| Burundi | Ongoing | Oct 25, 2017 by ICC Prosecutor after Pre-Trial Chamber authorisation (proprio motu) | Allegations of crimes against humanity (In Burundi and/or by nationals of Burundi outside Burundi since April 26, 2015 till Oct 26, 2017) | Both in and outside Burundi | |

| State of Palestine | Ongoing | May 22, 2018 by the State of Palestine | March 03, 2021 | Allegations of crimes within the jurisdiction of the Court (situation since June 13, 2014) | Occupied Palestine Territory (Gaza and West Bank, including East Jerusalem) |

| Bangladesh/Myanmar | Ongoing | Nov 14, 2019 by the ICC Prosecutor after Pre-Trial Chamber authorisation (proprio motu) | Allegations of crimes within the jurisdiction of the Court (situation in the People’s Republic of Bangladesh/Republic of the Union of Myanmar after June 01, 2010) | Rakhine State on the territory of Myanmar | |

| Afghanistan | Ongoing | March 05, 2020 by the ICC Prosecutor after Appeals Chamber authorisation (proprio motu) | Allegations of crimes within the jurisdiction of the Court (situation in the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan since May 01, 2003) | Throughout Afghanistan | |

| Republic of the Philippines | Ongoing | Sep 15, 2021 by the ICC Prosecutor after Pre-Trial Chamber authorisation (proprio motu) | Allegations of crimes within the jurisdiction, including but not limited to the crime against humanity of murder (Context of ‘war on drugs’ campaign in Philippines between Nov 01, 2011 & March 16, 2019 | Throughout Philippines | |

| Venezuela I | Ongoing | Sep 27, 2018 by a group of State Parties | Nov 03, 2021 | Allegations of crimes against humanity (situation in the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela since Feb 12, 2014) | Throughout Venezuela |

| Ukraine | Ongoing | March-April, 2022 by a 43 State Parties | March 02, 2022 | Allegations of crimes committed within the jurisdiction of the Court (situation in Ukrainian territory since Nov 21, 2013 | Ukraine |

Trial by the ICC

After investigations are concluded, the ICC where warranted conducts trials of individuals who are accused of having committed crimes against humanity, war crimes, genocide and crime of aggression. The status of trials conducted and presently being conducted at the ICC can be found on the official website under Situations and Cases.

History of the cases of ICC

The following is a compilation of the history of cases prosecuted by the ICC:

| Case | Status (Time of Warrant) | Charges/Conviction | Custody | Current Status |

| Abd-Al-Rahman | Alleged leader of Militia/Janjaweed | 31 counts: War Crimes & Crimes against Humanity (August, 2003 – April, 2004 in Darfur Sudan | In ICC Custody (since 09 June, 2020) | Closing statements in the Trial (11-13 December, 2024) |

| Abu Garda | Chairman and General Coordinator of Military Operations of the United Resistance Front | 3 counts: War Crimes (29 Sep, 2007 in Darfur, Sudan) | NA | Case Closed (Charges not confirmed and appeal application rejected) |

| Al Bashir | President of the Republic of Sudan | 10 counts: Crimes against Humanity, War Crimes & Genocide | At large | Warrant issued (Pre-Trial Stage until arrest & transfer to ICC) |

| Al Hassan | Alleged member of Ansar Eddine and de facto chief of Islamic police. Alleged to have been involved in the work of the Islamic court in Timbuktu. | Convicted of crimes against humanity of torture, persecution and other inhumane acts; and the war crimes of torture, outrages upon personal dignity, mutilation, cruel treatment and passing sentences without previous judgment pronounced by a regularly constituted court. | In ICC Custody (since 31 March, 2018) | Convicted and sentences guilty to 10 years of imprisonment. Notices of appeal against verdict filed. |

| Al Mahdi | Alleged member of Ansar Eddine, a movement associated with Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, head of the "Hisbah" until September 2012, and associated with the work of the Islamic Court of Timbuktu | Convicted and found guilty as a co-perpetrator of the war crime (directing attacks against religious and historic buildings in Timbuktu, Mali in June-July, 2012 | Surrendered to ICC Custody on 26 Sep, 2015 | Date of completion of sentence: 18 Sep, 2022 |

| Al-Werfalli | Commander in the Al-Saiqa Brigade | Alleged to have committed war crimes | Second warrant issued | Case closed (Prosecution notified of death of Al-Werfalli) |

| Banda | Commander-in-Chief of Justice and Equality Mouvement Collective-Leadership at time of warrant | 3 counts: War crimes (29 Sep, 2007 in Darfur, Sudan) | At large | Trial to commence pending arrest or appearance |

| Barasa | National of Kenya | 3 counts: offences against the administration of justice consisting of corruptly influencing or attempting to corruptly influence three ICC witnesses regarding cases from the situation in Kenya | At large | Pre-Trial stage pending arrest or appearance |

| Bemba | President and Commander-in-chief of the Mouvement de libération du Congo (Movement for the Liberation of Congo) (MLC) | 5 counts: Crimes against humanity & war crimes | Appearance on 04 July, 2008 | Acquitted by the Appeals Chamber |

| Bemba et al.

(5 persons) (Musamba, Bemba, Kabongo. Wandu & Arido) |

Nationals of DRC & CAR; | All five were convicted and found guilty of various offences against the administration of justice related to false testimonies in the Bemba case | Arrested on 23 Nov, 2013 | Convicted all five accused and imprisonment sentences were served. |

| Bett | Resident of Kenya | Charged with offences against the administration of justice in corruptly influencing witnesses (situation in Kenya) | At large | Pre-Trial stage pending arrest or appearance |

| Gaddafi (Muammar) | Libyan Head of State | 2 counts: Crimes against humanity (situation in Libya in 2011) | Warrant issued | Case closed on 22 Nov, 2011 (Following his death) |

| Gaddafi (Saif Al-Islam) | Libyan De-Facto Minister & Honorary Chairman of Gaddafi International Charity & Development Foundation | 2 counts: crimes against humanity | At large | Pre-Trial stage pending arrest or appearance |

| Gbabgo & Ble Goude | Ivorian Nationals; Latter was former President of Cote d’Ivoire | 4 counts: crimes against humanity | Arrested on 30 Nov 2011 & 22 March 2014 (resp.) | Case closed on 31 March, 2021 (Acquittal upheld by Appeals Chamber) |

| Ghaly | Malian Nationality; reasonable grounds to believe he was the leader of Ansar Eddine (controlled Timbuktu with Al Qaeda) | Charged with commission of war crimes and crimes against humanity | At large | Pre-Trial stage pending arrest or appearance |

| Gicheru | Lawyer based in Kenya | Charged with offences against the administration of justice in corruptly influencing witnesses (situation in Kenya) | Surrender on 02 Nov, 2020 | Case closed on 14 Oct, 2022 (following his death) |

| Harun | Minister of State for the Interior of the Government of Sudan | 42 counts: crimes against humanity & war crimes (between 2003-2004 in Darfur, Sudan) | At large | Pre-Trial stage pending arrest or appearance |

| Hussein | Minister of National Defence in Darfur, Sudan | 13 counts: crimes against humanity & war crimes (between 2003-2004 in Darfur, Sudan) | At large | Pre-Trial stage pending arrest or appearance |

| Katanga | Alleged commander of the Force de résistance patriotique en Ituri (FRPI) | Convicted and found guilty as an accessory of one count of crime against humanity and four counts of war crimes (24 Feb, 2003 attack on village of Bogoro, DRC) | In custody | Convicted and sentenced guilty to sentence of 12 years imprisonment on 23 May, 2014 (No further appeals) |

| Kenyatta | Deputy PM & Minister of Finance | 5 counts: crimes against humanity (2007-2008 post-election violence in Kenya) | Appearance on 08 April, 2011 | Case closed on 13 March, 2015 (Charges withdrawn dude to insufficient evidence) |

| Khaled | Alleged former Lieutenant General of Libyan Army & former head of the Libyan Internal Security Agency | 7 counts: crimes against humanity & war crimes (situation in Libya from March, 2011 to Aug, 2011) | Warrant issued | Case closed (Prosecution notified death of accused) |

| Kony | Alleged Commander-in-Chief of the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) | 36 counts: war crimes and crimes against humanity | At large | Confirmation of charges hearing will be held at a later date as the requirements to hold hearing in the absence of suspect is met |

| Lubanga | Former President of the Union des Patriotes Congolais/Forces Patriotiques pour la Libération du Congo (UPC/FPLC) | Convicted and found guilty of commission of war crimes | In custody | Convicted and sentenced guilty to imprisonment for 14 years – released on 15 March, 2020 on completion |

| Mbarushimana | Alleged Executive Secretary of the Forces Démocratiques pour la Libération du Rwanda - Forces Combattantes Abacunguzi (FDLR-FCA, FDLR) | 13 counts: crimes against humanity and war crimes (situation in Kivus, DRC in 2009) | Released from custody on 23 Dec, 2011 | Case closed (Pre-Trial Chambers declined to confirm the charges) |

| Mokom | CAR National; Alleged former National Coordinator of operations of the Anti-Balaka | 11 counts: war crimes & crimes against humanity (CAR region) | Appearance on 22 March, 2022 | Case closed on 17 Oct, 2023 (Prosecution withdrew charges on account of changes to evidence) |

| Mudacumura | Alleged Supreme Commander of the Forces Démocratiques pour la Libération du Rwanda | 9 counts: war crimes (situation in Kivus, DRC between 2009-2010) | At large | Pre-Trial stage pending arrest or appearance |

| Ngudjolo Chui | Leader of the Front des nationalistes et intégrationnistes (FNI) | 10 counts: war crimes & crimes against humanity (24 Feb, 2003 attack on Bogoro Village, DRC) | Released on 21 Dec, 2012 | Acquittal upheld by Appeals Chamber on 27 Feb, 2015 |

| Ntaganda | Former Deputy Chief of Staff and commander of operations of the Forces Patriotiques pour la Libération du Congo (FPLC) | Convicted and found guilty of 18 counts of war crimes & crimes against humanity (situation in Ituri, DRC from 2002-2003) | In custody | Convicted and sentenced to 30 years of imprisonment |

| Ongwen | Brigade Commander of the Sinia Brigade of the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), | Convicted and found guilty for 61 counts of crimes against humanity & war crimes (Northern Uganda from 2002-2005) | In custody | Convicted and sentenced to 25 years of imprisonment (Confirmed by Appeals Chamber) |

| Ruto & Sang | MP for Eldoret North & Head of Operations at Kass FMin, Kenya (resp.) | 3 counts: crimes against humanity (post-election violence in Kenya 2007-2008) | Appearance on 07 April 2011 | Case closed on 05 April, 2016 (Trial Chamber vacated the charges) |

| Said | National of CRA; Seleka Commander | Charged with war crimes and crimes against humanity (Bangui, CAR in 2013) | In custody | Ongoing Trial |

| Simone Gbagbo | Ivorian National | 4 counts: crimes against humanity | Warrant vacated on 29 July, 2021 | Case closed on 29 July 2021 (Pre-Trial Chamber found evidence insufficient) |

| Yekatom & Ngaissona | Former caporal-chief in the Forces Armées Centrafricaines, and a member of parliament in the CAR; and Alleged most senior leader and the "National General Coordinator" of the Anti-Balaka in Central African Republic (CAR) (resp.) | Charged with crimes against humanity & war crimes (situation in CAR, including areas of Bangui & Lobaye Prefecture. From Dec, 2013 to Aug, 2014. | In custody | Closing statements – Ongoing Trial |

India & the ICC

India is not a signatory of the Rome Statute and has not ratified the same, although it was an active participant in the Preparatory Committee for the Establishment of the ICC and the Rome Conference which was integral in the establishment of the international court. However, India abstained from the motion to adopt the Statute conducted towards the conclusion of the conference. During negotiations, India had raised objections to the Charter and demanded amendments suitable which were not incorporated into the final draft. This led to India and 20 other countries from abstaining from voting at the Conference and since has been disengaged from the ICC Process.

The following reasons underline the reason for abstention to ratify the Rome Statute:

Jurisdiction of the ICC

India did not support the ICC having any ‘inherent or compulsory jurisdiction’ stemming out of concerns that such a grant of inherent jurisdiction to an international court could compromise and ultimately infringe on the national sovereignty of member states. India asserted that the jurisdiction should be complementary to national jurisdiction and should not clash with the process of the national courts in the investigation and trial of such individuals. Although the need for an international criminal court was appreciated, India was apprehensive about a misuse of jurisdiction to investigate in areas with insurgency and militancy which are considered matters of internal deliberation. India was a proponent for a consent based system where the consent of territorial and custodial states are necessary for the Court to exercise jurisdiction (in all matters except genocide). India stressed that the ICC should only step in when the national system is unable or is non-existent and cannot deal with the specific crimes covered under the Statute, which is in conformity with the principle of territorial jurisdiction.

Role of the UN Security Council

India has also criticised the role of the UNSC in the ICC and represented the voices of the developing world to argue that any role granted to the UNSC can be misused by the Permanent Five. Such a link enabled the Security Council to have unfettered access to an international body that assumes neutral status otherwise which puts it in danger of corruption from within. India asserted that the UNSC as a political body should not compromise the independence of the Court as selective instances of justice may be sponsored, when political bias is involved. Moreover, India contended that the mandate of ‘maintenance of international peace and security’ accorded to the UNSC and the mandate of the ICC of that of a criminal justice funtion does not overlap and there is no legal and legitimate basis for the UNSC to refer matters to the ICC or have any role in its functioning. This, India contended, would constitute a violation of sovereign equality.

The Office of the Prosecutor

India was not a proponent of the jurisdictional powers of proprio motu granted to the Prosecutor due to scope for misuse for the furtherance of national and political agendas. Such an unfettered initiation of investigation, India contended, should be vested with the States and not to a designated official position. India believed this to be crucial in order to maintain the division between sovereign authority of the states and the profession responsibility of the prosecutor between which the lines should not be blurred. India was of the official position that the role of a Prosecutor should only begin post-authorisation and only in the capacity of gathering of evidence and conducting impartial investigations and prosecutions.

Non-inclusion of Nuclear Weapons

India had argued for the inclusion of the usage of nuclear weapons as a war crime within the purview of the ICC Statute, which failed to come through due to a lack of support from other delegations. India's position originated from the indiscriminate nature of these weapons and following the advisory opinion of the International Court of Justice which stated that the use of nuclear weapons was contrary to international humanitarian law.

Inclusion of Terrorism

India argued for the inclusion of terrorism as a crime of international concerns and submitted two proposals for inclusion of the same, to make it a crime against humanity and to include crimes of terrorism within the list of core crimes within the Statute. The rejection of these proposals was a major contributing factor to the reason why India decided to abstain from voting to adopt the Rome Statute.[46]

References

- ↑ Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, July 17, 1998, 2187 U.N.T.S. 90

- ↑ United Nations. 1948. Universal Declaration of Human Rights. https://www.un.org/en/udhrbook/pdf/udhr_booklet_en_web.pdf

- ↑ Office of the Historian. “Milestones in the History of U.S. Foreign Relations." https://history.state.gov/milestones/1914-1920/paris-peace

- ↑ United Nations General Assembly, A/RES/260(III)[A]

- ↑ "History of the ICC". Coalition for the International Criminal Court. Archived from the original on 7 March 2007.

- ↑ Scharf, Michael P. (August 1998). "Results of the Rome Conference for an International Criminal Court". American Society of International Law.

- ↑ Review of the ICC and the Rome Statute System, Coalition for the International Criminal Court, https://www.coalitionfortheicc.org/review-icc-and-rome-statute-system

- ↑ The Assembly of State Parties, Resolution ICC-ASP/18/Res.7

- ↑ Independent Expert Review of the International Criminal Court and the Rome Statute System Final Report, ICC-ASP/18/Res.7, September 2020, https://asp.icc-cpi.int/sites/asp/files/asp_docs/ASP18/ICC-ASP-18-Res7-ENG.pdf

- ↑ The Assembly of State Parties, Resolution ICC-ASP/19/Res.7

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Council on Foreign Relations. The Role of the International Criminal Court. Accessed December 10, 2024. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/role-icc.

- ↑ https://www.icc-cpi.int/asp

- ↑ Article 112, Rome Statute

- ↑ Article 34, Rome Statute

- ↑ Article 38, Rome Statute

- ↑ Article 39, Rome Statute

- ↑ Article 42, Rome Statute

- ↑ Article 43, Rome Statute

- ↑ Article 5, Rome Statue

- ↑ Article 6, Rome Statute

- ↑ Article 7, Rome Statute

- ↑ Article 8, Rome Statute

- ↑ Article 124, Rome Statute

- ↑ Article 8 bis, Rome Statute

- ↑ Article 12, Rome Statute

- ↑ Article 26, Rome Statute

- ↑ Article 11, Rome Statute

- ↑ Article 14, Rome Statute

- ↑ Article 15, Rome Statute

- ↑ Article 18, Rome Statute

- ↑ Article 53, Rome Statute

- ↑ Article 57, Rome Statute

- ↑ Article 59, Rome Statute

- ↑ Article 61, Rome Statute

- ↑ Article 53(1)

- ↑ Article 17, Rome Statute

- ↑ Article 64(8), Rome Statute

- ↑ Article 65, Rome Statute

- ↑ Article 74, Rome Statute

- ↑ Article 77, Rome Statute

- ↑ Article 81, Rome Statute

- ↑ Article 83, Rome Statute

- ↑ Situations under Investigations, ICC. https://www.icc-cpi.int/situations-under-investigations

- ↑ https://www.icc-cpi.int/cases

- ↑ https://www.icc-cpi.int/cases

- ↑ Devashees Bais, "India and the International Criminal Court", FICHL Policy Brief Series No. 54 (2016), https://www.toaep.org/pbs-pdf/54-bais