Money Laundering

What is Money Laundering?

As per Black’s Law Dictionary, money laundering is an offence that involves the act of transferring illegally obtained money, obtained as a result of criminal activities, through legitimate accounts or banking organisations to legitimise such gains, so that their original illegal source cannot be traced. In short, it is the processing of criminal proceeds to disguise their illegal origin in a way that enables the criminal to enjoy this money without jeopardising their source.

Official Definition of Money Laundering

Money Laundering as defined in legislation

In India, the Prevention of Money Laundering Act 2002 (PMLA) and the rules under it forms the core legal framework to combat money laundering. The offence of ‘Money Laundering’ is defined under Section 3 of the PMLA as “whoever directly or indirectly attempts or knowingly indulges or participates in any activity connected with proceeds of crime including its concealment, possession, acquisition or use and claims it as untainted property shall be guilty of the offence of money laundering”. In 2019, an explanation to Section 3 was added through an amendment to clarify that any person involved in any process or activity connected with the proceeds of crime including concealment, possession, acquisition or use or projecting or claiming it as untainted property is guilty of the the offence of money laundering till the time such person is involved in any such process or activity, the offence shall continue till such person is directly or indirectly attempting top indulge or knowingly assisting or knowingly is a part or is actually involved in any process or activity. The phrase ‘any process or activity’ emphasises the wide ambit of the definition and the clarification of money laundering as a continuing offence was introduced to rectify the misconception of money laundering as a one-time offence that ends once the proceeds of crime are concealed.

The Financial Intelligence Unit of India (FIU-IND) and the Enforcement Directorate (ED) have been conferred with power to implement the provisions of the Act. The FIU-IND plays a pivotal role in coordinating and aiding the efforts of national investigative agencies and international agencies in combating global money laundering and terrorism financing since it has the primary mandate of receiving, processing and disseminating information related to suspicious financial transactions. The ED operates within the Revenue Department under the Ministry of Finance and is the primary agency for investigating and prosecuting offences relating to money laundering under the PMLA. Additionally, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) and Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority of India (IRDAI) are also authorised to make anti-money laundering guidelines and address such issues.

Under Indian law, the offence of money laundering is prosecuted along with the underlying criminal offence. Known as a ‘predicate offence’ or ‘scheduled offence’, the PMLA provides a list of such offences in a Schedule appended to it. Section 2(1)(y) of the Act defines ‘scheduled offence’ as offences specified under Part A of the Schedule or under Part B of the Schedule, if the total value involved is one crore rupees or more or those specified under Part C of the Schedule. The offences listed in the Schedule are drawn from various legislations including Indian Penal Code 1860, Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act 1985 (NDPS), Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act 1967 (UAPA), Prevention of Corruption Act 1988, Securities and Exchange Board of India 1992 etc. The Finance Minister while introducing the 2012 amendment to the PMLA noted that for registering an offence under the PMLA, there must be a predicate offence which is connected to the proceeds of the crime.

The term ‘proceeds of crime’ is defined in Section 2(1)(u) of the PMLA 2002 to mean any property directly or indirectly obtained as a result of criminal activity relating to a scheduled offence or the value of such property. Where such property is held outside the country, then the proceeds of crime are taken as property equivalent in value to such held within the country or abroad. The explanation to this section clarifies that proceeds of crime includes any property directly or indirectly obtained as a result of criminal activity relatable to the scheduled offence.

Under Section 11A, 12, 12A and 12AA of the Act, ‘reporting entities’ such as banking company, financial institution, intermediary or person carrying on designated business or profession are required to maintain records of all transactions including information furnished to the FIU-IND to enable it to reconstruct individual transactions. Such records need to be maintained for a minimum period of 5 years. If reporting entities fail to comply with obligations under Chapter IV of the PMLA, the Director of the ED can, post an inquiry, issue written warnings, directions or impose monetary penalties upto rupees one lakh for each failure. It is also provided that no civil or criminal proceedings can be initiated against any reporting entity or its directors and employees for furnishing such information. Section 15 provides the procedure for furnishing such information by reporting entities.

Provisions of Chapter III earlier made confiscation of proceeds of crime contingent on prior seizure and attachment of property by the Adjudicating Authority with provision of appeals to Appellate authorities such as the high courts and Supreme Court which limited the power of confiscation under the PMLA. Sections 5 and 8 of the PMLA were amended by the PMLA Amendment Act 2012 to ensure that confiscation of property laundered was no longer dependent on conviction for scheduled offence and only a registration at the judicial level of investigation for the predicate offence was required, whether in India or abroad. Section 65 of the PMLA also refers to the applicability of sections of the Criminal Procedure Code for the purpose of confiscation of proceeds of crime besides arrest, search seizure, attachment, investigation and prosecution. Subsequent amendments to related provisions in the UAPA, NDPS and Companies Act 2013 were made to harmonise the confiscation of property from offences therein. The Central government in 2023 also included cryptocurrencies and non-fungible tokens (NFTs) within the ambit of the PMLA to ensure that such transactions also comply with the Act and also issued notices to Virtual Digital Assets Service Providers to comply with the Act.[1]

Section 5 also empowers the ED to attach proceeds of crime for a period not exceeding 180 days where there is reason to believe that such property amounts to proceeds of crime. Section 17(1A) of the PMLA empowers the ED to issue orders freezing property in cases where seizure is impractical or where property cannot be transferred without prior permission. Further, section 60 also empowers the ED to confiscate assets on conclusion of trial in a money laundering case.

Section 19 of the Act provides that the arresting officer must inform the arrestee of the grounds of arrest ‘as soon as maybe’ when being arrested for the offence of money laundering under the Act.

Section 44 of the PMLA provides that any offence punishable under Section 4 and any connected scheduled offence shall be triable by the Special Court constituted for such purpose. Such court shall try the offence of money laundering or the scheduled offence according to the provisions of the Code of Criminal Procedure as it applies to a trial before a sessions court. Further, the powers of the high court regarding bail under the Code of Criminal Procedure also continue to apply. By a 2019 amendment, an explanation was added to Section 44 which stated that the jurisdiction of the Special Court while dealing with offences under the Act shall not be dependent upon any orders passed in respect of the scheduled offence and the trial of both sets of offences by the same court shall not be construed as a joint trial.

Section 45 of the PMLA provides twin conditions that need to be satisfied for the grant of bail - one, that the Public Prosecutor needs to be given an opportunity to oppose the bail application and second, the Court is satisfied that there are reasonable grounds to believe that the applicant is not guilty of the alleged offence were required to be mandatorily complied with. The proviso to Section 45 of the PMLA provides an exception that empowers the Special Court to grant bail on humanitarian grounds or a person under 16 years, or sick or infirm.

Section 54 of the PMLA endows certain officers of the Custom and Central Excise departments, income tax authorities, members of stock exchanges, officers appointed under the NDPS. police officers, officers of the Pension Fund Regulatory and Development Authority (PFRDA), IRDAI, department of posts and others appointed under any Central or State act as defined in the requisite notification.

Section 56 of the Act also provides powers to the Central Government to enter into agreements with foreign countries for enforcing the provisions of the PMLA and exchanging information for the prevention of the offence of money laundering. Such reciprocal arrangements give the Act cross border implications with extra-territorial applicability.

Section 70 provides that if any corporate entity violates any provision of the PMLA, individuals in charge of the entity and accountable for its operations at the time of the offence along with the entity shall be liable for the breach of provisions under the Act unless they are able to prove that such money laundering took place without their knowledge or that they exercised due care and auction to ensure compliance with applicable laws and guidelines. Hence, it can be seen that the offence of money laundering is not a strict liability offence and requires the element of knowledge and mens rea to be proven.

Money laundering as defined in case law

Ambit of the offence of money laundering

In Rohit Tandon v Directorate of Enforcement[2], the Supreme Court examined the interplay of various aspects of the offence of money laundering under Section 3 and held that ‘..there is no allegation in the charge-sheet filed in the scheduled offence case or prosecution complaint that the unaccounted cash deposited by the appellant is the result of criminal activity. Absent this ingredient, the property derived or obtained by the appellant would not become proceeds of crime’. The Court referred to the definition of ‘proceeds of crime’ under Section 2(1)(u), ‘property’ under Section 2(1)(v) and ‘scheduled offence’ under Section 2(1)(y) to observe that while the expression ‘criminal activity’ has not been defined under the Act, it refers to activities that form a part of the predicate offence which contains the requirement of mens rea. Hence, the concealment, possession, acquisition or use of property by projecting or claiming it as untainted property when connected to a scheduled offence would be within the ambit of Section 3 and punishable by Section 4 of the PMLA.

The Delhi high court in M/s Mahanivesh Oils & Foods Pvt. Ltd v Directorate of Enforcement[3] noted that the PMLA owes its inception to joint initiatives taken by the international community to identify and curb the threat of money laundering and since India is a signatory to such international initiatives, the Prevention of Money Laundering Bill 1999 was introduced with the objective to ‘enact comprehensive legislation inter alia for preventing money laundering and connected activities, confiscation of proceeds of crime, setting up of agencies and mechanisms for combating money laundering etc’.

Necessity of scheduled offence in relation to offence of money laundering

There is some controversy related to the necessity and timing of predicate offence in relation to the offence of money laundering with conflicting judgments between the Supreme Court and various High Courts across the country, owing to the explanation added to Section 44 of the PMLA through the 2019 amendment.

The necessity of establishing commission of scheduled offence for the offence of money laundering to be made out has been laid down in the landmark case of Vijay Madanalal Choudhary and Ors. v Union of India[4] and Ors. and P Chidambaram v Directorate of Enforcement[5].

In P Chidambaram v Directorate of Enforcement[6], the Supreme Court held that a scheduled offence is a sine qua non for the offence of money laundering as the proceeds of crime must directly or indirectly originate from criminal activities associated with the predicate offence.

In Vijay Madanalal Choudhary and Ors. v Union of India and Ors.[7], a three judge bench of the Supreme Court held that if the predicate offence fails, then prosecution for money laundering under the PMLA cannot continue by the ED. The Court cited the former Finance Minister, Mr P Chidamabaram who, while introducing the Prevention of Money Laundering (Amendment) Bill 2012 to amend the definition of money laundering to align it with the global standard as per the recommendation of the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), stated that “..money laundering is a very technically defined offence. It postulates that there must be a predicate offence and it is dealing with the proceeds of a crime. That is the offence of money laundering. It is more than simply converting black money into white or white money into black. That is an offence under the Income Tax Act. There must be a crime as defined in the Schedule. As a result of that crime, there must be certain proceeds - it could be cash; it could be property. And anyone who directly or indirectly indulges or assists or is involved in any activity connected with the proceeds of crime and projects it as untainted property is guilty of the offence of money laundering. So, it is a very technical offence. The predicate offences are all listed in the Schedule. Unless there is a predicate offence, there cannot be an offence of money laundering."

The Court also clarified that there is no linkage between the dates of the predicate offence and the commission of the offence of money laundering. As a result, only the date on which acts under Section 3 are committed will be relevant for the offence of money laundering. This interpretation has led to situations where predicate offence has not been notified or conversion of proceeds of crime has happened before the commencement of the PMLA but since the offence of money laundering has happened after the commencement of the Act, such acts/ offences are still investigated under the PMLA. This is also a landmark judgment which upheld the constitutional validity of the provisions in the PMLA related to arrest, search, seizure, summons and raids.

In Babulal Verma and Ors. v Enforcement Directorate and Ors.[8], the Bombay high court interpreted this explanation to mean that once the money laundering offence is registered on the bases of a scheduled offence, it stands on its own and does not require the support of the predicate offence. Further, it has been held in this case that even if the scheduled offence is compromised/ quashed/ compounded/ the accused has been acquitted, the investigation by the ED can continue. The Court interpreted the Supreme Court’s observations in the P Chidambaram case to mean that the predicate offence is necessary only for the initiation of investigation by the ED into the offence of money laundering and thereafter, the trials would be conducted separately. This has been reiterated by the Bombay high court in the case of Radha Mohan Lakhotia v Deputy Director, PMLA, Department of Revenue[9] wherein the court held that an investigation into the offence of money laundering is not dependent on the ultimate result of the scheduled offence as it is a completely independent investigation. It was further held that on a strict interpretation of Sections 3 and 4 of the PMLA, it can be deduced that the person being investigated under the Act need not be charged with committing a scheduled offence - it is only needed for registering the ECIR and the ultimate outcome of the investigation need not have any bearing on proceedings under the PMLA.

However, other high courts have taken the opposite approach. The Karnataka high court in Obulapuram Mining Company Pvt. Ltd v Joint Director, Directorate of Enforcement[10] held that the ECIR was liable to be quashed since the predicate offence of the petitioners did not fall within ‘scheduled offences’ under the Act.

The Delhi high court in Rajiv Chanana v Deputy Director of Enforcement[11] observed that the acquittal of a person of charges of a scheduled offence erodes the foundation of the offence of money laundering. Similarly, in Arun Kumar Mishra v Directorate of Enforcement[12], the Delhi high court quashed the ECIR based on two underlying FIRs where a closure report was filed in one and the petitioner was exonerated in the other.

The issue of provisional attachment orders under Section 5 of the PMLA even when no proceedings related to scheduled offence have been initiated was dealt with by the Delhi high court in Prakash Industries v Union of India[13]. The ED had taken action in this case solely on its own opinion that the material gathered in the course of investigation was evidence of predicate offence without any such offence being registered by the relevant authorities. The court held that the ED cannot assume that a scheduled offence has been committed if it finds material during investigation of money laundering. The scheduled offence needs to be within the cognisance of a competent investigative agency and registered with the police or pending enquiry before a competent forum. As a result, the provisional attachment orders were quashed since they were issued on a future prospective action.

The Finance Act 2019 amended Section 44 of the PMLA which deals with offences triable by Special Courts to include the explanation that the jurisdiction of the Special Court while dealing with offence under the PMLA shall not be dependent upon orders passed in respect of the scheduled offence. Further, the trial of the scheduled offence and the offence of money laundering shall not be construed as a joint trial.

The territorial jurisdiction of the Special Court was dealt with in the case of Rana Ayyub v Enforcement Directorate[14] where the petitioner was accused of money laundering through an online crowdfunding platform and was tried for the offence by the Special Court, Ghaziabad. The Court interpreted Section 44 with certain provisions of the Criminal Procedure Code to mean that the Special Court could try even the scheduled offence. Since the proceeds of crime were transferred virtually from different places, each Special Court having jurisdiction over such territorial area would have jurisdiction to try the offence as each of them constitute places where any activity/ process related to the offence in Section 3 occurred.

Arrest and bail for the offence of money laundering under the PMLA

In Pankaj Bansal v Union of India[15], the Supreme Court held that it was mandatory for the ED to provide reasons for arrest in writing to the person arrested under the PMLA. The court referred to its judgments in Vijay Madanlal Choudhary v Union of India[16] and V Senthil Balaji v The State represented by Deputy Director[17] to observe that Section 19 of the PMLA does not provide how an arrestee is to be informed of the grounds of their arrest while Article 22 of the Indian Constitution lays down that a person needs to be informed of the grounds of their arrest as a fundamental right and held that the arrestee must be informed of the grounds of his arrest in writing as a matter of course without exception. This requirement was prospective from the date of the judgment.

In Ram Kishor Arora v ED[18], the Supreme Court held that the ED need not immediately provide the reasons for arrest and the same could be provided to the arrestee within 24 hours of their arrest. Since the time within which such reasons for arrest were not clarified in Pankaj Bansal, the court interpreted the phrase ‘as soon as may be’ in Section 19(1) of the Act to mean ‘as early as possible without avoidable delay’ or ‘within reasonably convenient’ or ‘reasonable time’. The Court held that the person arrested must be informed of the grounds of their arrest within 24 hours of the arrest which is also the period within which the person needs to be produced before the Special Court. However, the court also noted that since the three judge bench in Vijay Madanlal Choudhary held that Section 19 of the PMLA was compliant with Article 21 of the Constitution, observations made by benches of lower strength cannot override it. Hence, the Supreme Court’s observations in Pankaj Bansal should be considered per incuriam since it was a two judge bench judgment.

Recently, in Tarsem Lal v Directorate of Enforcement, Jalandhar Zonal Office[19], the Supreme Court held that ED cannot exercise powers under Section 19 to arrest an accused person once the Special Court takes cognisance of the complaint and that furnishing bonds under Section 88 of the Criminal Procedure Code is merely an undertaking to appear before court when required which is not equivalent to bail and hence, the twin conditions for bail under Section 45 were inapplicable.

The case of Vijay Madanlal Choudhary[20] is fairly controversial since it was held that an arrested person is not entitled to claim a copy of the ECIR as a matter of right. Hence, since the details in the ECIR are rarely disclosed, the arrested person usually has no knowledge of the case against them, even at the stage of remand hearing. Hence, by laying down a requirement to inform the arrested person of the grounds of their arrest in writing within 24 hours has introduced procedural fairness in favour of the accused.

However, there have been divergent views among high courts on whether oral communication of grounds of arrest is compliant with the law. The Madras high court in Megala v State[21], held that a procedural defect in arrest by not providing grounds of arrest in writing is cured by the remand order passed by the sessions court/ magistrate since custody/ detention is the result of such order only.

The Supreme Court in Vijay Madanlal Choudhary also upheld the reverse burden of proof and the twin conditions for bail under Section 45 of the Act namely, the Public Prosecutor needs to be given an opportunity to oppose the bail application and the Court is satisfied that there are reasonable grounds to believe that the applicant is not guilty of the alleged offence were required to be mandatorily complied with. However, this judgment is pending review before the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court in Anoop Bartaria v Enforcement Directorate[22] held that offences under the PMLA were cognisable and non bailable as per the explanation to Section 45. As a result, authorities under the Act have the power to arrest without warrant after fulfilling conditions specified in Section 19 and 45 of the PMLA. In Directorate of Enforcement v M Gopal Reddy[23], the Supreme Court held that rigorous twin conditions mentioned in Section 45 of the PMLA would be applicable to the filing of anticipatory bail under Section 438 of the Criminal Procedure Code also.

Money Laundering as defined in other international documents

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC)

The Vienna Convention against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances 1988

The United Nations Convention against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances 1988 (Vienna Convention) includes the definition of money laundering in Article 3.1(b) and (c) as ‘the conversion or transfer of property, knowing that such property is derived from any offence(s), for the purpose of concealing or disguising the illicit origin of the property or of assisting any person who is involved in such offence(s) to evade the legal consequences of his actions’ and adds that money laundering also involves ‘acquisition, possession or use of property, knowing at the time of receipt that such property was derived from an offence'[24]. However, the Vienna Convention limits the predicate offences to drug trafficking offences only as a result of which other offences related to money laundering were left out.

The United Nations Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime 2000

The limitations of the Vienna Convention have been addressed in other international instruments like the United Nations Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime 2000 (Palermo Convention) which requires all participating countries to apply money laundering offence to the ‘widest range of predicate offences’. Articles 6 and 7 deal with combating money laundering while Articles 12, 13 and 14 deal with confiscation of proceeds of crime[25]. This Convention also operates under the aegis of the UNODC.

The United Nations Convention Against Corruption 2004

Under this Convention, Articles 14, 23 and 24 deal with measures to combat money laundering while Articles 31, 51 to 59 contain provisions for freezing and confiscating proceeds of crime[26]. The secretariat for this Convention operates from the UNODC and the ED is the agency for international cooperation under this treaty.

Financial Action Task Force (FATF)

The FATF is an intergovernmental organisation established in 1989 as an international watchdog to combat money laundering, terrorist financing and related threats to the integrity of the international finance system of which India has been a member since 2010. The FATF has set international standards on the definition of money laundering by taking the wide definition used in the Vienna Convention and the Palermo Convention and recommended to member countries to expand the list of predicate offences to include serious crimes, as a result of which money laundering was no longer limited to drug related offences. This led to the definition of the offence of money laundering in Section 3 of the PMLA.

Mutual Evaluation Report

The FATF placed India in the ‘regular follow up’ category in its latest Mutual Evaluation Report in 2024 under the anti-money laundering (AML) and counter-terrorist financing (CFT) recommendation stating that it has an ‘effective system’ but needs ‘major improvements’ to strengthen prosecution in these cases. This is a distinction shared by only four other G20 countries including the United Kingdom. The FATF regularly evaluates every country through peer review where representatives from other countries examine the AML regime in the country, consult requisite authorities, gather statistics and examine the regulations dealing with money laundering. This evaluation results into every country being rated by the FATF based on its 40 recommendations as ‘Non Compliant’ (NC), ‘Partially Compliant’ (PC), ‘Largely Compliant’ (LC) or Fully Compliant (FC/C) with respect to one parameter or the other. The previous evaluation report for India was undertaken in 2010, following which the first recommendation pointed out that the definition of money laundering under Section 3 of the PMLA was not consistent with the Vienna and Palermo Conventions since it did not include the physical concealment and acquisition/ possession of proceeds of crime. As a result, the definition was amended as per the PMLA (Amendment) 2012 to include these elements and make it globally compliant.

The FATF recognised India’s attempts in mitigating risks from ML/TF, effective measures taken to transition from a cash based to a digital economy and its implementation of the JAM (Jan Dhan, Aadhaar, Mobile) trinity which increased financial inclusion and increased traceability of digital transactions, thereby mitigating risks of ML/TF[27].

The FATF listed the following areas for improvement including limited number of prosecutions, risk-profiling of customers of financial institutions, monitoring of the Ministry of Corporate Affairs registry for availability of accurate owner information and the link between money laundering and human trafficking. It noted that India’s main sources of money laundering are from within and terrorist threats from the north, north-east and left wing extremists, significantly the Islamic State and Al Qaeda linked groups active in Jammu and Kashmir. Further, the FATF mentioned that the largest money laundering risks relate to cyber fraud, corruption and drug trafficking and India should ensure that its non-profit organisations are not being abused for terrorist financing.

The FATF has also observed that India also needs to improve its framework for implementing targeted financial sanctions to ensure freezing of funds and assets and to identify politically exposed persons (PEPs). While the government has defined foreign PEPs as ‘individuals entrusted with prominent public functions by a foreign country’, domestic PEPs are undefined.

Official Database

Open Government Data Platform India

The Open Government Data Platform India which has been developed as part of the Digital India Initiative, provides a compilation of certain data related to the offence of money laundering under the PMLA that has been shared in the public domain by the Parliament. There are related to -

- Number of ECIRs filed under the PMLA from 2019-2024.[28]

- Number of Prosecution Complaints filed under the PMLA from 2019-2024.[29]

- Number of Companies against which Prosecution Complaints have been filed from 2019-2024.[30]

- Number of accused who have been convicted under the PMLA from 2018-2023.[31]

- Number of Investigations initiated under the PMLA from 2015-2020.[32]

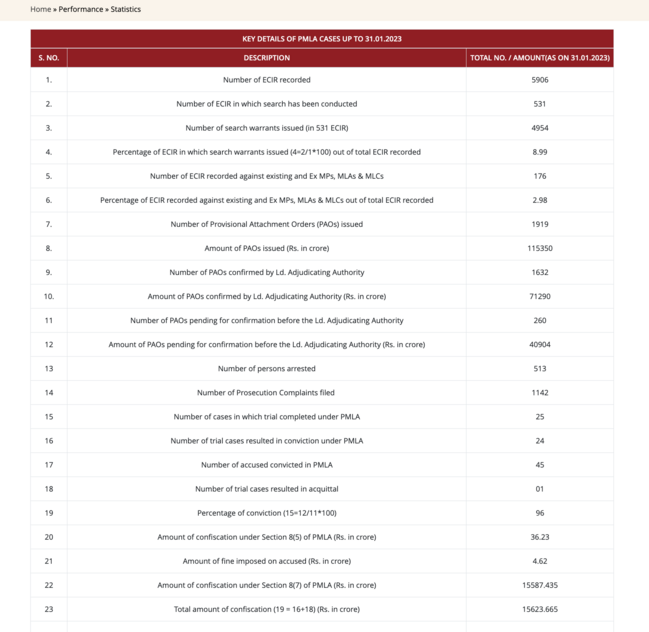

Enforcement Directorate

The ED also provides statistics related to PMLA cases on its website which have been updated upto 31 January 2023.[33]

Research that engages with Money laundering

Spotlight: Why PMLA Scheduled Offences need a fresh look? (CAM Blogs)

The blogpost by Bharat Vasani & Varun Kannan

References

- ↑ PIB, FIU-IND issues show cause notices to nine offshore Virtual Digital Assets Service Providers, 28 December 2023, Available at - https://pib.gov.in/pressreleasepage.aspx?prid=1991372

- ↑ 2018 (11) SCC 46.

- ↑ 228 (2016) DLT 142.

- ↑ [2022] 6 SCR 382.

- ↑ AIR 2020 SC 1699.

- ↑ AIR 2020 SC 1699.

- ↑ [2022] 6 SCR 382.

- ↑ 2021 SCC OnLine Bom 392.

- ↑ 2010 (5) BomCR 625.

- ↑ ILR 2017 Karnataka 1846.

- ↑ 2015 (316) ELT 422 (Del).

- ↑ 2015 SCC OnLine Del 8658.

- ↑ 2023 SCC Online Del 336.

- ↑ (2023) 4 SCC 357.

- ↑ Criminal Appeal No. 3051-3052 of 2023.

- ↑ 2022 SCC Online SC 929.

- ↑ Criminal Appeal No. 2284-2285 of 2023.

- ↑ 2023 SCC OnLine SC 1682.

- ↑ Special Leave to Appeal (Crl) No. 121 of 2024.

- ↑ 2022 SCC Online SC 929.

- ↑ 2023 SCC Online Mad 4711.

- ↑ 2023 SCC Online SC 477.

- ↑ Criminal Appeal No 534 of 2023.

- ↑ United Nations, UN Convention against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances 1988, Availabe at -https://www.unodc.org/pdf/convention_1988_en.pdf

- ↑ United Nations, UN Convention against Transnational Organised Crime, Available at - https://www.unodc.org/documents/treaties/UNTOC/Publications/TOC%20Convention/TOCebook-e.pdf

- ↑ United Nations, UN Convention against Corruption, Available at - https://www.unodc.org/documents/treaties/UNCAC/Publications/Convention/08-50026_E.pdf

- ↑ PIB, FATF lauds India's efforts to combat Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing, 28 June 2024, Available at - https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=2029297

- ↑ Data taken from starred question no. 157 answered by Shri Javed Ali Khan in Rajya Sabha session no. 265. Available at - https://sansad.in/rs/questions/questions-and-answers

- ↑ Data taken from starred question no. 157 answered by Shri Javed Ali Khan in Rajya Sabha session no. 265. Available at - https://sansad.in/rs/questions/questions-and-answers

- ↑ Data taken from starred question no. 157 answered by Shri Javed Ali Khan in Rajya Sabha session no. 265. Available at - https://sansad.in/rs/questions/questions-and-answers

- ↑ Data taken from unstarred question no. 559, asked by Shri Raghav Chadha and answered by Shri Pankaj Chaudhary in Rajya Sabha session no. 257. Available at - https://sansad.in/rs/questions/questions-and-answers

- ↑ Data taken from unstarred question no. 1665 asked by Shri Naresh Gujral and answered by Shri Anurag Singh Thakur in Rajya Sabha session no. 250. Available at - https://sansad.in/rs/questions/questions-and-answers

- ↑ Available at - https://enforcementdirectorate.gov.in/statistics-0