Motor Accident Claims

What are Motor Accident Claims?

Motor accident claims refer to the legal remedies available to victims of motor vehicle accidents or their legal representatives. These claims typically seek compensation for injuries, fatalities, or property damage resulting from road accidents.

Official Definition of 'Motor Accident Claims'.

The Motor Vehicles Act, 1988, under Chapter X, XI, and XII, provides a comprehensive framework for motor accident claims.[1] Section 165 of Motor Vehicles Act, 1988 constitutes Motor Accident Claims Tribunals (MACTs) to adjudicate claims for compensation arising from motor accidents involving the death of or bodily injury to persons.

No Fault Liability Claim

- The principle of No-Fault Liability is enshrined in Section 140 of Motor Accident Act, 1988. According to this principle, the claimant(s) can obtain instant compensation without having to prove negligence, guaranteeing prompt financial comfort. Nonetheless, the amount of compensation under this section are fixed to Rs. 50,000 in respect of death of any person and Rs. 25,000 in respect of permanent disablemen t of any person, allowing claimants to seek greater compensation under other clauses.

Hit-and-run motor accidents

A road accident where identity of the motor vehicle causing death or injury to the person(s) is not known is called “Hit and Run Motor Accident”. Section 161 of Motor Accident Act, 1988 provides for compensation for hit-and-run motor accidents. As per the Hit and Run Motor Accident Compensation Scheme-2022 the compensation payable to Hit and Run victims, with effect from 1st April 2022, at Rs 2,00,000 for death and Rs 50,000 for grievous hurt. How to claim compensation?

- Application for compensation, is required to be submitted by the injured victim himself/ herself or dependent/ legal representative of the death victim to Claims Settlement Commissioner of the district where the respective accident has taken place.

- Duly completed Formats I, II, III & IV, along with supportive documents are required to be sent by the respective district authorities to General Insurance Council by post or to the Council’s dedicated e-mail id i.e. [email protected]

- Payments for successful applications are released by the Council directly into the bank accounts of the beneficiaries.

- Formats I, II, III & IV, required for this purpose, can be downloaded from the link provided below.

Section 163-A-

This was added by the 1994 amendment, offers compensation according to a methodical formula that is listed in the Act's Second Schedule. Using a multiplier based on the victim's age and yearly income, this method determines compensation, deducting one-third to cover personal expenses. At least Rs. 50,000 is given to the claimants, plus extra for burial costs, consortium loss, and estate loss.

Section 173-

Provides for an appeal process in cases where a person is dissatisfied with the award passed by the Claims Tribunal under the Act. It allows the claimant or the insurer to appeal the decision to the High Court. The appeal must be filed within a specified period, which is typically 90 days from the date of the award. This provision ensures that the parties have a legal recourse to challenge the tribunal's decision if they believe it to be unjust.

As defined in case laws

- case name

MV ACT: SUPREME COURT TO HEAR PLEAS CHALLENGING SIX MONTHS LIMITATON TO FILE MOTOR ACCIDENT COMPENSATION CLAIMS

The Supreme Court (on April 01) issued a notice in a writ petition challenging the constitutional validity of Section 166 (3), which was added through the Motor Vehicles (Amendment) Act, 2019. As per this provision, a claim for compensation on account of a motor vehicle accident must be filed before the Motor Accidents Claims Tribunal within six months from the date of the accident.

The provision, which took effect on April 1, 2022, has now been challenged on the ground that it curtails the rights of road accident victims by imposing a strict six-month limitation period for filing claim applications. It has been further argued that putting such a cap on filing the claim application undermines the object of this benevolent statute, which is intended to provide benefits to victims of road accidents.

Based on this projection, the petitioner has pleaded that the impugned amendment is not only arbitrary but also violates the fundamental rights of the road accident victims.

"Declare the amendment w.e.f, 1.4.2022 in view of the Government Notification is arbitrary, ultra-vires and violative of Articles 14, 19 and 21 of the constitution of India and deserves to be set aside," the petition stated.

A Bench of Justices Sudhanshu Dhulia and Prasanna Bhalachandra Varale issued notice on the petition to the Union of India.

It may also be noted that the Motor Vehicles Act of 1939 was amended by the 1988 Act, whereby a claim petition was to be filed within six months. However, by way of the amendment in 1994, the time limit was removed for filing a claim petition regarding an accident that occurred at any time. The legislature, with the introduction of Act 32 of 2019, which came into effect on 1.04.2022, brought back the old provisions of 166(3), restricted the entertainment of the compensation application unless it is made within six months from the occurrence of the accident. For ready reference, Section 166 (3) reads as:

"(3) No application for compensation shall be entertained unless it is made within six months of the occurrence of the accident."

The petitioner has also challenged the impugned amendment because the legislation did not consider any opinion or refer to any law commission report or parliamentary debate behind it. In addition, the effective stakeholders were not consulted during the process.

"The objection and reason behind such amendment is completely silent in the fact and circumstances of the present case, which is one of the most relevant aspect before enacting any new statutory provision or any amendment to the existing provision of a Statute. Hence, this present Writ Petition is in order to protect the interest of the road users and accident victims suffered in view of Motor Vehicles in public place.," the petition added.

In view of this, it has been submitted that the impugned regulation is "unreasoned, arbitrary and irrational" and violates the fundamental rights of the road accident victims.

Case Title: BHAGIRATHI DASH v. UNION OF INDIA & ANR., Writ Petition(s)(Civil) No(s). 166/2024

Click Here To Read/Download Order

PROCEDURE FOR INVESTIGATION OF MOTOR VEHICLE ACCIDENTS 1. Investigation of road accident cases by the Police Immediately on receipt of the information of a road accident, the Investigating Officer of Police shall inspect the site of accident, take photographs/videos of scene of the accident and the vehicle(s) involved in the accident and prepare a site plan, drawn to scale, as to indicate the layout and width, etc., of the road(s) or place(s), as the case may be, the position of vehicle(s), and person(s) involved, and such other facts as may be relevant. In injury cases, the Investigating Officer shall also take the photographs of the injured in the hospital. The Investigating Officer shall conduct spot enquiry by examining the eyewitnesses/bystanders. 2. Intimation of accident to the Claims Tribunal and Insurance Company within forty-eight (48) hours The Investigating Officer shall intimate the accident to the Claims Tribunal within forty-eight (48) hours of the accident, by submitting the First Accident Report (FAR) in Form-I. If the particulars of insurance policy are available, the intimation of the accident in Form-I shall also be given to the Nodal Officer of the concerned Insurance Company of the offending vehicle. A copy of Form-I shall also be provided to the victim(s), the State Legal Services Authority, Insurer and shall also be uploaded on the website of State Police, if available. 3. Rights of victims of Road Accident and Flow Chart of the Scheme mentioned in Form II to be furnished by the Investigating Officer to the Victim(s) The Investigating Officer shall furnish the description of the rights of victim(s) of road accidents and flow chart of the Scheme mentioned in Form-II, to the victim(s), or their legal representatives, within ten (10) days of the accident. The Investigating Officer shall also file a copy of Form-II along with the Detailed Accident Report (DAR) 4. Driver’s Form to be submitted by the driver to the Investigating Officer The Investigating Officer shall provide a blank copy of Form-III to the driver of the vehicle(s) involved in the accident and the driver shall furnish the relevant information in Form-III to the Investigating Officer, within thirty (30) days of the accident. 5. Owner’s Form to be submitted by the owner The Investigating Officer shall provide a blank copy of Form-IV to the owner(s) of the vehicle(s) involved in the accident and the owner(s) shall furnish the relevant information in Form-IV to the investigating Officer, within thirty (30) days of the accident.

Procedure for Investigation of Motor Vehicle Accidents

- Investigation of road accident cases by the Police

- Intimation of accident to the Claims Tribunal and Insurance Company within forty-eight (48) hours

- Rights of victims of Road Accident and Flow Chart of the Scheme mentioned in Form II to be furnished by the Investigating Officer to the Victim(s)

- Driver’s Form to be submitted by the driver to the Investigating Officer

- Owner’s Form to be submitted by the owner

- Interim Accident Report (IAR) to be submitted by the Investigating Officer to the Claims Tribunal

- Verification of the Driver’s Form and Owner’s Form by the Investigating Officer and Insurance Company

- Victim’s Form to be submitted by the victim(s) to the Investigating Office

- Victim’s Form to be submitted by the victim(s) in respect of minor children

- Verification of the Victim’s Forms by the Insurance Company

- Investigation of the criminal case to be completed by the police within sixty (60) days of the accident

- DAR to be submitted by the Investigating Officer before the Claims Tribunal

- Investigating Officer may seek necessary directions from the Claims Tribunal

- Duty of the Registering Authority to verify the documents

- Duty of the hospital to issue MLC (Medico Legal Case) and Postmortem Report

- Examination of FAR, IAR and DAR by the Claims Tribunal

- Duty of the Investigating Officer to produce the driver(s), owner(s), claimant(s) and eye witness(es) before the Claims Tribunal

- Duties of Police shall be construed to be part of State Police Act

- Claims Tribunal shall treat DAR as a claim petition for compensation under subsection (4) of section 166 of the Motor Vehicles Act, 1988

- Cases of rash and negligent driving

- Duty of the Insurance Companies to appoint a Designated Officer within ten (10) days of the receipt of the copy of DAR

- Duty of the Insurance Companies to appoint a Nodal Officer and intimate the State Police.

- Duty of Insurance Companies to verify the claim

‘Motor Accident Claims’ as defined in Official Reports:

This 119th Law Commission Report (1987) report recommended the establishment of specialized Motor Accident Claims Tribunals (MACTs) to provide a streamlined and efficient mechanism for handling compensation claims arising from motor accidents. The report emphasized the need to reduce the burden on regular civil courts, promote faster resolution of cases, and ensure that victims or their legal representatives receive timely justice. The report also recommended amending section 110A(2) so as to provide that every claim application shall be made to the Claims Tribunal having jurisdiction over the area in which the accident occurred, or to the Claims Tribunal within the local limits of whose jurisdiction the claimant resides or carries on business or personally works for gain or within the local limits of whose jurisdiction the defendant resides or carries on business or works for gain, at the option of the claimant.[2]

‘Motor Accident Claims’ as defined in Case Laws:

Union of India v. Sunil Kumar Ghosh

In Union of India v. Sunil Kumar Ghosh[3], the court distinguished between routine events inherent to activities and those unexpected occurrences that qualify as accidents or mishaps. It observed An accident refers to an unforeseen event or occurrence that takes place unexpectedly, surprising those involved. It is characterized by the unexpected rather than the anticipated. Essentially, an event that is ordinarily expected during a routine activity, such as a rail journey, cannot be classified as an accident. In contrast, an accident involves the happening of something that deviates from the usual course of events and is not inherent to the normal conditions of an activity. It denotes a mishap resulting from circumstances that are unusual and unpredictable.

Smt. Alka Shukla v. Life Insurance Corporation of India

In Smt. Alka Shukla v. Life Insurance Corporation of India[4], the Supreme Court dealt with the interpretation of accident benefit clauses in insurance policies. The primary issue was whether both 'the means causing the injury or death' and 'the outcome' itself must be accidental for an insurance claim to succeed.

The Court held that to sustain a claim under an accident benefit cover, the claimant must establish a clear causal link between the accident and the bodily injury. The injury must result solely and directly from the accident without interference from any other cause. Furthermore, the accident must be caused by external, violent, and visible means.

The judgment also emphasized that the injury must independently and directly lead to the assured's death within 180 days of the accident. This condition requires the injury to be the proximate and exclusive cause of death, without the influence of other factors.

Senior Divisional Manager, National Insurance Company Ltd. v. Sayeeda Khatoon (2009)-

This case clarified the interpretation of the phrase "accident out of the use of a motor vehicle." The Court held that this expression refers to situations where a motor vehicle is directly involved in an accident, resulting in death or disablement of its occupants or other individuals impacted by the vehicle's movement. The provision does not extend to compensating individuals involved in unrelated incidents, such as kidnappers or hijackers killed by villagers, merely because they were using a motor vehicle.

Ranju Rani alias Ranju Devi v. Branch Manager, The New India Assurance Company Limited (2002)-

In this case, the issue was whether the death of an individual, alleged to have resulted from a motor vehicle incident, qualified for compensation under Section 163-A of the Motor Vehicles Act. The Tribunal ruled that the death in this instance was a case of "murder simpliciter" rather than an accident involving the use of a motor vehicle. Consequently, it did not meet the criteria for compensation under the Act.

Sri Nagarajappa v. The Divisional Manager, The Oriental Insurance Co. Ltd. (AIR 2011 SC 1785)-

In this case, the Supreme Court outlined a three-step approach to assess the impact of permanent disability on a claimant's earning capacity. This process is critical for determining compensation in motor accident cases involving physical impairment.

The first step requires the Tribunal to ascertain the activities that the claimant can still perform despite the disability and identify those they can no longer carry out. This assessment also influences compensation under the category of loss of life amenities.

The second step involves examining the claimant’s avocation, profession, and nature of work prior to the accident, along with their age. This helps evaluate how the disability has affected their pre-accident capabilities.

In the third step, the Tribunal determines the extent of the disability by evaluating whether the claimant is (i) completely unable to earn a livelihood, (ii) capable of performing their previous tasks without significant impairment, or (iii) restricted to limited or alternative activities to maintain some form of livelihood.

Arvind Kumar Mishra v. New India Assurance Co. Ltd. & Anr. (AIR SCW 6085)-

A similar approach was emphasized in this case where the Court highlighted the necessity of carefully correlating disability with its impact on earning capacity, ensuring fair and just compensation for accident victims.

As defined in Official Documents:

Scheme for Motor Accident Claims

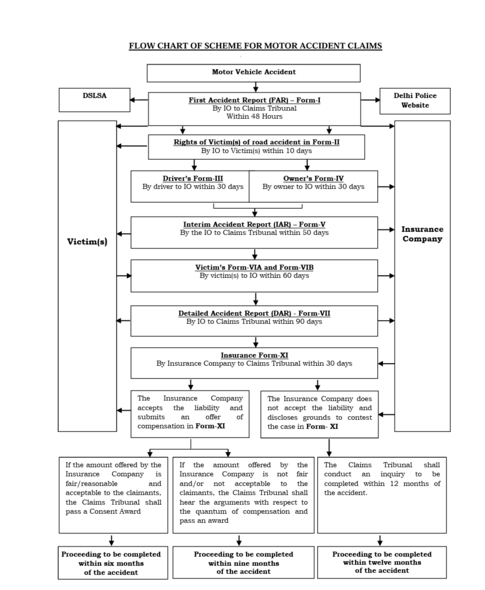

The Delhi High Court’s “Scheme for Motor Accident Claims” was implemented from 2nd April 2021 to ensure time-bound, fair, and efficient disposal of motor accident claims. Recognising the human tragedy of road accidents and their socio-economic impact, the scheme aims to provide quick compensation to victims and their families, addressing delays and bottlenecks in the previous system.

The scheme was formulated to replace the earlier “Claims Tribunal Agreed Procedure” and is a product of continuous improvement, including orders from the Supreme Court in Jai Prakash v. National Insurance Co. and M. R. Krishna Murthi v. New India Assurance Co. It lays down a detailed timeline and process for police, insurance companies, victims, and claims tribunals to follow, ensuring transparency and speedy justice.

The first step involves the Investigating Officer (IO) submitting a First Accident Report (FAR) in Form-I to the Claims Tribunal within 48 hours of an accident. This report is also shared with the victims, the Delhi State Legal Services Authority (DSLSA), and uploaded online for transparency. Within 10 days, victims are provided Form-II outlining their rights and the scheme’s flowchart.

The driver and vehicle owner must submit Forms III and IV respectively within 30 days, disclosing crucial details like license validity, insurance, and vehicle fitness. Insurance companies are mandated to appoint Nodal Officers and Designated Officers to ensure accountability and speedy verification of claims. The scheme introduces an Interim Accident Report (IAR) to be filed within 50 days and a Detailed Accident Report (DAR) within 90 days of the accident. The DAR, considered as a claim petition under Section 166(4) of the Motor Vehicles Act, must be shared with all stakeholders including victims, insurers, and DSLSA.

The Claims Tribunal is required to treat the DAR as a claim petition and conduct an inquiry to determine liability and compensation. If the insurance company accepts liability and offers fair compensation, a consent award is issued. Otherwise, the Tribunal must decide the claim within nine to twelve months of the accident.

For monitoring compliance and resolving issues, a Committee comprising a High Court judge, DSLSA’s Member Secretary, a Police Commissioner’s nominee, an official from the Ministry of Road Transport and Highways, and the Secretary General of the General Insurance Council was set up. This Committee ensures monthly reports are filed by police and insurance companies, proposes remedial measures, and oversees the effective implementation of the scheme.

This scheme has set a high standard for other jurisdictions, with its emphasis on digitisation, including convenient digitalised forms, electronic submission of reports, and periodic reviews. Overall, it reflects a significant step forward in ensuring quick and fair compensation for motor accident victims in Delhi.

Motor accident claims are broadly categorized based on whether the claimant needs to prove fault or whether compensation is provided without establishing negligence. These distinctions ensure that victims of road accidents, regardless of the specifics of their cases, can receive compensation. The two primary types of claims are no-fault claims and fault-based claims, each governed by different provisions under the Motor Vehicles Act, 1988.

Under Section 163-A of the Motor Vehicles Act, victims of motor vehicle accidents are entitled to compensation without having to prove that the driver was at fault. This section introduces the concept of liability without fault, a victim-centric approach designed to provide quicker relief to accident victims, especially in cases where proving negligence might be challenging.

In contrast to the no-fault claims, fault-based claims require the claimant to prove that the accident was caused due to the negligence or fault of the vehicle’s driver. Under Section 166 of the Motor Vehicles Act, the claimant must show that the accident was caused by the driver's failure to adhere to traffic laws or exercise reasonable care, resulting in harm. To do this, the claimant must gather various forms of evidence. This includes the First Information Report (FIR) filed with the police, which outlines the details of the accident and helps establish the driver’s involvement. Additionally, medical reports that document the extent of the injuries sustained are crucial for demonstrating the severity of the harm caused. Eyewitness testimony and photographs of the scene can further support the claim by providing an independent account of the incident. In more complex cases, accident reconstruction reports may be used to demonstrate the exact cause of the accident and the driver’s fault.

International Experience.

New Zealand:

New Zealand is one of the most well-known proponents of a no-fault compensation system through its Accident Compensation Corporation (ACC). Under this system, any individual who suffers an injury, including motor vehicle accidents, is entitled to compensation regardless of who is at fault. The system covers a wide range of costs, including medical treatment, rehabilitation, loss of income, and in some cases, pain and suffering. The goal is to reduce the burden of legal proceedings on both the claimant and the insurer, allowing for quicker resolution and support for injured individuals.

Canada:

Canada has implemented no-fault insurance schemes in several provinces, such as Ontario and Quebec. These systems allow accident victims to claim compensation directly from their own insurer without proving negligence. However, the right to sue for additional damages (for example, for pain and suffering) may still be available in certain cases, particularly if the injury is severe or permanent. Ontario’s system is based on a threshold test, where only those who suffer significant injuries are entitled to sue for non-economic damages. This strikes a balance between ensuring victims' access to compensation and reducing unnecessary litigation.

United Kingdom:

The United Kingdom operates primarily under a fault-based system. In cases where a person is injured in a motor accident, they must establish the negligence of the other party to claim compensation. The Road Traffic Act of 1988 provides a framework for compensating victims of road traffic accidents, and the Motor Insurers Bureau (MIB) plays a critical role in compensating victims when the at-fault driver is either unidentified or uninsured. Claimants must go through an insurance process, and if disputes arise, they can seek recourse through the civil courts.

Australia:

In Australia, motor vehicle accident claims are governed by a mixture of both fault-based and no-fault systems, depending on the state or territory. For example, in New South Wales, the system is partially no-fault, allowing victims of motor accidents to claim certain benefits, such as medical expenses, regardless of fault. However, if the accident results in serious injury or death, the victim may pursue a fault-based claim against the responsible party for compensation beyond the basic benefits provided by no-fault insurance. Other states like Victoria follow a similar pattern, offering a hybrid model where victims can access immediate benefits without proof of fault but can later pursue a negligence claim.

International Frameworks-

The European Union has harmonized certain aspects of compensation for motor vehicle accidents through directives such as the Directive 2009/103/EC. This directive mandates that all motor vehicles be insured, sets up an efficient claims process for victims, and establishes a guarantee fund to cover victims when the responsible driver is unidentified or uninsured. Additionally, the EU ensures that victims can pursue claims in their home country if they are involved in accidents in other EU nations, making cross-border compensation more accessible.

Calculation of Claims.

The Madhya Pradesh High Court has developed a “Claim Calculator Software” to assist in estimating compensation for motor accident claims. This tool is designed to provide advocates, litigants, and insurance companies with a reliable way to calculate tentative compensation amounts in Motor Accident Claims Tribunal (MACT) cases. It operates within the legal framework established by landmark Supreme Court judgments, including those in the Sarla Verma and Pranay Sethi cases, which standardize the calculation of just compensation. The software requires key inputs such as the type of injury (death or permanent disability), the name of the deceased, details of the accident, and other relevant personal data. It then uses this information to calculate compensation based on accepted formulas and factors like age, income, and dependents. Accessible via the Madhya Pradesh High Court’s official website, this digital tool streamlines the claims process, reduces disputes over compensation amounts, and ensures greater consistency and transparency in motor accident claim proceedings.

Multiplier Method:

The multiplier method is a judicially accepted and standardized approach for calculating just compensation in motor accident claims, particularly for cases involving death or permanent disability. This method aims to ensure uniformity, predictability, and fairness in awarding compensation by linking it to the victim’s earning capacity and the dependency of their family.

Step 1: Determination of Annual Income

The first step involves establishing the annual income of the deceased or injured person at the time of the accident. This includes their salary, wages, or business income. In some cases, courts may also consider future prospects, acknowledging the likelihood of wage increases or promotions. For instance, in National Insurance Co. Ltd. v. Pranay Sethi (2017), the Supreme Court ruled that future prospects must be added to the income, depending on the age and employment status of the deceased.

Step 2: Deduction for Personal Expenses

Next, a deduction is made to account for the personal expenses of the deceased, as they would have spent a portion of their earnings on themselves. Generally, one-third of the income is deducted for unmarried individuals and one-fourth for married individuals, leaving the “annual loss of dependency” amount.

Step 3: Selection of the Multiplier

The “multiplier” is then selected based on the age of the deceased or injured person at the time of the accident. The landmark case Sarla Verma v. Delhi Transport Corporation (2009) laid down a structured table to determine the appropriate multiplier, balancing life expectancy and earning potential. For example:

Age 15–20: Multiplier 18

Age 21–25: Multiplier 18

Age 26–30: Multiplier 17

Age 31–35: Multiplier 16

Age 36–40: Multiplier 15

Age 41–45: Multiplier 14

Age 46–50: Multiplier 13

…and so on, reducing with increasing age. Step 4: Final Compensation for Loss of Dependency The final compensation for “loss of dependency” is calculated by multiplying the “annual loss of dependency” with the chosen multiplier. For example, if the annual loss is ₹2,00,000 and the multiplier is 15, the compensation will be ₹30,00,000.

Step 5: Additional Heads of Compensation

Apart from the loss of dependency, additional heads of compensation are awarded, which include:

- Loss of consortium (for spouse)

- Loss of care and guidance (for children)

- Funeral expenses

- Medical expenses (if injury-related)

- Loss of estate The Supreme Court in Pranay Sethi provided standard amounts for these heads to ensure uniformity.

References

- ↑ https://morth.nic.in/sites/default/files/MV%20Act%201988-Chapter%2012.pdf

- ↑ ONE HUNDRED NINETEENTH REPORT ON ACCESS TO EXCLUSIVE FORUM FOR VICTIMS OF MOTOR ACCIDENTS UNDER THE MOTOR VEHICLES ACT, 1939; Chapter III; pp. 12 accessible at https://cdnbbsr.s3waas.gov.in/s3ca0daec69b5adc880fb464895726dbdf/uploads/2022/08/2022080884-1.pdf

- ↑ 1985 SCR (1) 555

- ↑ AIR 2019 SC 2088