National Green Tribunal

What is National Green Tribunal

The National Green Tribunal (NGT) is a quasi-judicial body in India, constituted to deal with cases relating to environmental protection and conservation of forests and other natural resources, including enforcement of legal rights relating to environment and giving relief and compensation for damages to persons and property and for matters connected therewith or incidental thereto. It is a specialized body equipped with the necessary expertise to handle environmental disputes involving multi-disciplinary issues.

The National Green Tribunal Act, 2010, which succeeded the National Environment Tribunal Act, 1995, made significant changes to the adjudicatory mechanism related to environmental rights. Under the new Act, the Tribunal is empowered to hear cases related to environmental concerns, and is required to pass orders within 6 months of the institution of any case.

The Tribunal was officially established in October 2010, under section 3 of the NGT Act.[1][2] Originally, its place of sitting was New Delhi. However, in 2011, under section 4(3) of the NGT Act, Bhopal, Pune, Kolkata, and Chennai were recognized as places of sitting as well.[3][4]

The Supreme Court, recognizing the role of a separate tribunal for speedy administration of justice, upheld the power of the Central Government to establish the NGT, in the case of Madhya Pradesh High Court Advocates Bar Association and Anr. v. Union of India.[5] In doing so, the Court also recognized the jurisdiction of High Courts to hear appeals from the NGT.

Official Definition of National Green Tribunal

National Green Tribunal as defined in the National Green Tribunal Act, 2010

Section 2(1)(n). "Tribunal" means the National Green Tribunal established under section 3.[6]

Section 3. Establishment of Tribunal.—The Central Government shall, by notification, establish, with effect from such date as may be specified therein, a Tribunal to be known as the National Green Tribunal to exercise the jurisdiction, powers and authority conferred on such Tribunal by or under this Act.[7]

Legal provisions relating to National Green Tribunal

Constituting Act

The Central Government has constituted the National Green Tribunal (NGT) under section 3 of the NGT Act (19 of 2010) w.e.f. 18th October 2010. The Tribunal was officially established vide S.O. 2569 (E) and S.O. 2570(E) of 18.10.2010, which provided 18 October, 2010 as the date on which the NGT Act, 2010 would enter into force,[8] and officially established the Tribunal, and appointed Shri Justice L.S. Panta as its first Chairperson.[9]

The Act outlines the jurisdiction, powers, and procedure of the Tribunal. Apart from it, the following Rules guide the procedure for appointment and conduct of the Tribunal:

- National Green Tribunal (Manner of Appointment of Judicial and Expert Members, Salaries, Allowances and otherTerms and Conditions of Service of Chairperson and other Members and Procedure for Inquiry) Rules, 2010.

- National Green Tribunal (Practice and Procedure) Rules, 2011.

- National Green Tribunal (Financial and Administrative Powers), Rules, 2011.

Jurisdiction

Sections 14 and 16 of the NGT Act lay down the Tribunal's original and appellate jurisdictions respectively.[10]

Section 14. Tribunal to settle disputes.—(1) The Tribunal shall have the jurisdiction over all civil cases where a substantial question relating to environment (including enforcement of any legal right relating to environment), is involved and such question arises out of the implementation of the enactments specified in Schedule I.

(2) The Tribunal shall hear the disputes arising from the questions referred to in sub-section (1) and settle such disputes and pass order thereon.

(3) No application for adjudication of dispute under this section shall be entertained by the Tribunal unless it is made within a period of six months from the date on which the cause of action for such dispute first arose:

Provided that the Tribunal may, if it is satisfied that the applicant was prevented by sufficient cause from filing the application within the said period, allow it to be filed within a further period not exceeding sixty days.

Further, under section 16, any order/direction/decision made or issued after the commencement of the National Green Tribunal Act, 2010, by any authority under the Acts listen in Schedule 1 may be appealed to the Tribunal.

The Tribunal's jurisdiction extends to the following statutes, listed in Schedule I:

- The Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1974;

- The Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Cess Act, 1977;

- The Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980;

- The Air (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1981;

- The Environment (Protection) Act, 1986;

- The Public Liability Insurance Act, 1991;

- The Biological Diversity Act, 2002.[11]

Further, under sections 15 and 17, the Tribunal has the power to order relief, restitution, or compensation for damage to property or the environment in specific circumstances.[12]

S.O. 1003 (E) of 05.05.2011 notified New Delhi as the ordinary place of sitting of the National Green Tribunal, having jurisdiction over the entirety of India.[13] Three months later, S.O. 1908 (E) of 17.08.2011 established New Delhi, Bhopal, Kolkata, Chennai, and Pune as the ordinary places of sitting of the Tribunal, with Delhi as the Principal place of sitting.[14] The jurisdiction of each Place was notified as follows:

| Zone | Place of Sitting | Territorial Jurisdiction |

|---|---|---|

| Northern | New Delhi (Principal) | Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Punjab, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Jammu & Kashmir, National Capital Territory of Delhi, Union Territory of Chandigarh |

| Western | Pune | Maharashtra, Gujarat, Goa, Union Territory of Daman and Diu and Dadra and Nagar Havelli |

| Central | Bhopal | Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Chhattisgarh |

| Southern | Chennai | Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Union Territory of Puducherry, Union Territory of Lakshwadweep |

| Eastern | Kolkata | West Bengal, Bihar, Orissa, Jharkhand, Sikkim, seven sister states of North-Eastern region, Union Territory of Andaman and Nicobar Islands |

Governance Structure

Under section 3 of the NGT Act,[15] the Tribunal shall consist of the following members:

- Chairperson: The Tribunal is presided by a full time Chairperson.

- Judicial Members: The Tribunal may consist of 10 - 20 Judicial Members, as determined by the Central Government.

- Expert Members: The Tribunal may consist of 10 - 20 Expert Members, as determined by the Central Government.

- Special Invitees: The Chairperson may invite any person having specialized knowledge and experience in a particular case to assist the Tribunal.

Provisions relating to members of the Tribunal

Qualifications

Under section 5 of the NGT Act,[16] the qualifications to serve as a member of the Tribunal are:

- Chairperson: Person who is a retired Judge of the Supreme Court of India or Chief Justice of a High Court.

- Judicial Members: Person who is a retired Judge of the Supreme Court, or Chief Justice or Judge of a High Court.

- Expert Members: Person who-

- possesses a Doctoral degree or Master of Engineering or Master of Technology with 15+ years of experience in the relevant field, including 5 years of practical experience in the fields of environment and forests at a reputed national institute; or

- possesses 15+ years of administrative experience, including 5+ years of environmental experience at the Central Government, State Government, or a reputed National/State institute.

According to section 5(3), the Chairperson, Judicial Members, and Expert Members must not be holding any other office during their tenure on the Tribunal. The are also generally barred from holding any office or participate in the management of any person or company who has been a party before the Tribunal for a period of 2 years after leaving office.

| In 2011, while making the first appointments, the following guidelines were provided by the Central Government, which have informed various future appointments.

For Judicial Member:

For Expert Member:

|

Appointment

Under section 6(2) of the NGT Act, the Chairperson of the Tribunal must be appointed by the Central Government, in consultation with the Chief Justice of India.[18]

Judicial Members and Expert Members of the Tribunal shall be appointed by the Central Government, considering the recommendations of the Selection Committee.

The Selection Committee is designed to include individuals with expertise in environmental matters. This ensures that members appointed to the NGT possess the necessary knowledge and experience to effectively adjudicate environmental cases. Under the National Green Tribunal (Manner of Appointment of Judicial and Expert Members, Salaries, Allowances and other Terms and Conditions of Service of Chairperson and other Members and Procedure for Inquiry) Rules, 2010,[19] the Selection Committee is composed of the following members:

- Sitting Judge of the Supreme Court, nominated by the Chief Justice of India in consultation with the Minister of Law & Justice - Chairperson;

- Chairperson of the National Green Tribunal - Member ex officio;

- Secretary to the Government of India in the Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change - Member ex officio;

- Director, Indian Institute of Technology, Kanpur - Member;

- Director, Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad - Member;

- President, Centre for Policy Research, New Delhi - Member.

Term of Office

Under section 7 of the NGT Act,[20] the Chairperson, Judicial Members, and Expert Members serve for a term of 5 years, or

- if the Chairperson/Judicial Member is a Judge of the Supreme Court, till the attainment of 70 years of age, whichever is earlier;

- if the Chairperson/Judicial Member is the Chief Justice of a High Court, till the attainment of 67 years of age, whichever is earlier;

- if the Judicial Member is a Judge of a High Court, till the attainment of 65 years of age, whichever is earlier;

- for Expert Members, till the attainment of 65 years of age, whichever is earlier.

The Chairperson, Judicial Members, and Expert Members are not eligible for re-appointment.

Salary and Allowances

Section 9 of the NGT Act governs the prescription of salary and allowances for the Chairperson and Members of the Tribunal. It reads:

Section 9. Salaries, allowances and other terms and conditions of service.—The salaries and allowances payable to, and the other terms and conditions of service (including pension, gratuity and other retirement benefits) of, the Chairperson, Judicial Member and Expert Member of the Tribunal shall be such as may be prescribed:

Provided that neither the salary and allowances nor the other terms and conditions of service of the Chairperson, Judicial Member and Expert Member shall be varied to their disadvantage after their appointment.[21]

Chapter III of the National Green Tribunal (Manner of Appointment of Judicial and Expert Members Salaries, Allowances and other Terms and Conditions of Service of Chairperson and other Members and Procedure for Inquiry) Rules, 2010 govern the salary payable to the Chairperson and members. They include:

- Chairperson: such salary and allowances admissible to a sitting Judge of the Supreme Court;

- Judicial Members: such salaries and allowances admissible to a sitting Judge of a High Court;

- Expert Members: such salaries and allowances admissible to a Secretary to the Government of India.[22]

Removal and Resignation

The Chairperson, Judicial Member and Expert Member of the Tribunal may resign their office by writing a letter to the Central Government.[23]

Further, the Central Government, in consultation with the Chief Justice of India, may remove the Chairperson, Judicial Members, or Expert Members, if they meet any of the following conditions:

- has been adjudged an insolvent;

- has been convicted of an offence which, in the opinion of the Central Government, involves moral turpitude;

- has become physically or mentally incapable;

- has acquired such financial or other interest as is likely to affect prejudicially his functions;

- has so abused his position as to render his continuance in office prejudicial to the public interest.

However, the removal of the Chairperson or Judicial Members may only be affected after an inquiry is conducted by a Judge of the Supreme Court, and such Member is given an opportunity of being heard. Until such inquiry, the Central Government may suspend such Member from their office.

Further, Expert Members may be removed only after they have been given an opportunity to be heard.[24]

According to Chapter IV of the National Green Tribunal (Manner of Appointment of Judicial and Expert Members Salaries, Allowances and other Terms and Conditions of Service of Chairperson and other Members and Procedure for Inquiry) Rules, 2010, the Central Government is required to conduct a preliminary inquiry for removal of the Chairperson, Judicial Members, and Expert Members. Thereafter, if satisfied, it may refer the same to the following Committee for further inquiry:

- Cabinet Secretary - Chairperson ex officio;

- Secretary, Ministry of Environment, Forests & Climate Change - Member ex officio;

- Secretary, Department of Legal Affairs, Ministry of Law & Justice - Member ex officio;

The Committee is required to submit its report to the President, who may remove Expert Members under the NGT Act, or, in the case of the Chairperson or Judicial Members, institute an inquiry by a Judge of the Supreme Court.[25]

Procedure & Practice

Section 4(4) of the NGT Act allows the Central Government, in consultation with the Chairperson of the National Green Tribunal, to prescribe rules governing the procedure and practice of the Tribunal.[26]

Pursuant to this power, the National Green Tribunal (Practice and Procedure) Rules, 2011 were published in April 2011. They have been further amended in 2017 and 2023.

Under rule 3, the Chairperson may constitute Benches of two or more members, with at least one Judicial Member and one Expert Member, and allocate the matters to be dealt with by each such bench. However, as of 2017, the Chairperson may constitute a single-member bench in exceptional circumstances.[27]

The Tribunal also consists of a Registrar, who receives all applications and appeals to the Tribunal. Subsequently, he may scrutinize submitted documents, and seek rectification of any defects.[28]

Under the Act, the Tribunal is not bound by the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908. Instead, it is guided by the principles of natural justice.[29] Therefore, the Tribunal is allowed to pass ex-parte orders and dispose cases without the parties present.[30]

'NGT' as defined in International Instruments

Agenda 21, UN Conference on Environment & Development, 1992

Agenda 21 was a landmark environment and climate change adopted at the UN Conference on Environment & Development, held at Rio de Janeiro, Brazil in 1992. The document officially recognized global warming, and delineated 21 different goals for the countries to achieve. Alongside this, the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was also adopted at this Conference.[31]

Chapter 8 of Agenda 21 describes the goal of 'Integrating Environment & Development in Decision-Making'. Part B of the Chapter recommends the establishment of judicial and administrative procedures for strengthening environmental laws. The specific recommendation adopted by the Conference was:

"Governments and legislators, with the support, where appropriate, of competent international organizations, should establish judicial and administrative procedures for legal redress and remedy of actions affecting environment and development that may be unlawful or infringe on rights under the law, and should provide access to individuals, groups and organizations with a recognized legal interest."[32]

The NGT Act was inspired by this recommendation. The Preamble of the Act explicitly recognizes the inspiration from Agenda 21, alongside the growing environmental consciousness resulting after the 1972 Stockholm Conference.[33]

Environmental Courts & Tribunals: A Guide for Policy Makers, 2016

In 2016, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) unveiled the Environmental Courts & Tribunals Study, conducted by George & Catherine Pring. The study analyzed 1000+ Environmental Courts & Tribunals (ECTs) across the world, and made specific recommendations for strengthening them.

The study's detailed analysis of the NGT revealed that "the NGT has the powers and features of a civil court, including the power to summons, conduct discovery, receive evidence, requisition public records, sanction for contempt and issue cost orders, interim orders and injunctions – so it is something of an Environmental Tribunal and Environmental Court “hybrid.” Its jurisdiction is limited to 7 major environmental laws, and, typical of ETs, it does not have criminal jurisdiction. It has the power to regulate its own procedures (although the Central Government also has some rule-making authority over it). It is not bound by the general courts’ Code of Civil Procedure or Rules of Evidence, but is to apply principles of “natural justice” and International environmental law, including sustainable development, precautionary and polluter pays principles."[34]

The study's recommendations for ECTs are reproduced below:

- Mission: A clear statement of a mission to ensure access to justice, environmental democracy, the rule of law and sustainability.

- “Just, quick and cheap”: An explicit requirement to provide access to justice that is fair, efficient and affordable.

- Independence: Language creating decisional independence from external influence, administrative independence from government bodies whose decisions it reviews and institutional independence relating to appointment, tenure and remuneration.

- Expertise: Provision for both law-trained judges and science-technical decision makers trained and experienced in environmental issues who are competent, diverse, unbiased, ethical and committed to service and justice.

- Flexibility: Substantial freedom for the ECT to control its own rules and procedures (including standing, costs, remedies and enforcement and the ability to make future changes without requiring new authorization).

- ADR: In-house provision of ADR for cases in which it could improve outcomes.

- Budget: Adequate, independent, protected financial resources not subject to political retaliation.

- Integrated jurisdiction: Broad, comprehensive, integrated jurisdiction over the full range of environmental and land use planning laws.

- Information technology: Provision for a progressive, full-service IT system.

- Prosecutors: Authorization for trained specialized environmental prosecutors.

- Triple jurisdiction: Jurisdiction granted over civil, criminal and administrative cases.

- Levels: ECTs at both trial and appeal levels (and possibly Supreme Court).

- Natural resource damages (NRD): A procedure that permits government to recover money to restore, replace, or repair public natural resources, such as land, fish and wildlife, ecosystems, parks, forests, air, water, groundwater, and other resources held in trust for the public.

- Public interest litigation (PIL): Authorization for lawsuits against public or private parties for actions and inactions harmful to public health or the environment.

- Anti-SLAPPs Protection: An expedited dismissal procedure to protect litigants and others from “Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation” (“SLAPPs”), unjust lawsuits filed to intimidate and silence those seeking to protect the environment.

- Referral Process: Procedures for referring to it environmental cases filed in other courts.

- Evaluation: Requirement for regular, in-depth evaluation processes based on performance indicators.[35]

Many of these recommendations have also been adopted by the NGT in India. The NGT is composed of both Judicial & Expert Members, who are independent from government or corporate influence. The NGT has integrated jurisdiction across India, and has also adopted IT services. It also allows PILs and has specific provisions for referral by higher courts.

Environmental Courts & Tribunals: A Guide for Policy Makers, 2021

In 2021, the UN Environmental Programme refreshed the 2016 study on Environmental Courts & Tribunals (ECTs), focussing on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on these ECTs.

The Report, while assessing the performance of the NGT, pointed out the fact that there have been some issues with it's operation so far: “The Tribunal’s test of independence and expertise is in its function as the appellate authority. It is surprising if the NGT shies away from hearing appeals on merit, even when they are filed within 90 days. Not even 1 per cent of projects are appealed against and the appellants, often project affected people from the hinterlands, deserve to be heard within the limits of reasonability."[36] Further, per the report, the number of environmental cases has been declining in India since 2018. It has been observed that the decrease in caseload is attributable, inter alia, to perceptions of a less receptive NGT as a result of a change in leadership, as well as litigation fatigue on the part of civil society actors.[37]

National Green Tribunal as defined in Official Documents

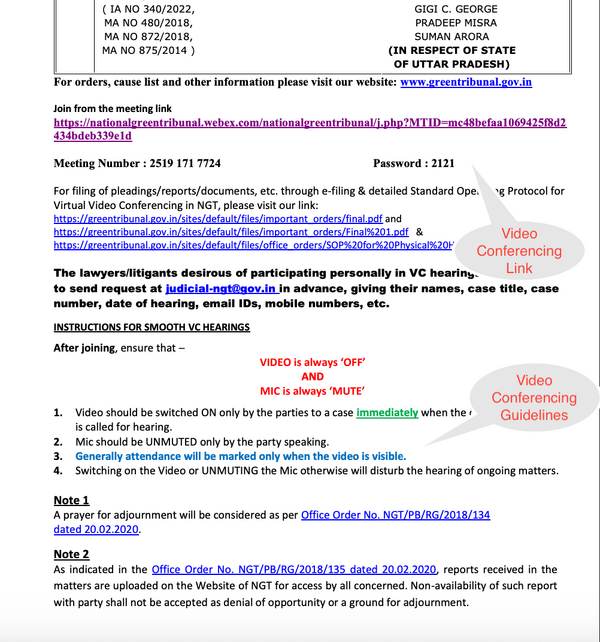

Office Order No. NGT(PB)/DR/2018-19/68/570 regarding Video Conferencing, 2018

In 2018, the NGT officially began using Video Conferencing at specific times across the 4 Zonal Benches. This was further extended to the Principal Bench, and permitted for all days of the week in 2020.[38]

Notice regarding Procedure for Application for Exemption from Fees, 2021

In 2021, a notice was issued that allowed applicants/appellants who fell Below Poverty Line or were indigent, who were exempt from Court Fees under the NGT (Practice & Procedure) Rules, 2011 to send all documents in support of their claim at [email protected] for being listed before the concerned Registrar for decision on the said issue.[39]

Office Order No. NGT (PB)/Judicial/16/2020/390 regarding SOP for Video Conferencing & E-Filing, 2024

In 2024, the National Green Tribunal notified comprehensive Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) regarding virtual video conferencing and e-filing on their website. Some of the key information therein included:

- All pleadings/affidavits/reports should be filed in searchable PDF format and not in photo PDF format, to the extent possible. The reports received by NGT in cases shall be uploaded on website for perusal of the parties for prior access and response, if any.

- For video conferencing, the NGT shall be using Cisco-Webex application.

- Any user entering the VC room with any other username or in any other format or with unidentifiable username or in any other format or with unidentifiable username, shall be logged out and shall be requested to join again with correct format.

- As soon as the matter is taken up, parties are expected to switch on their video. Once the parties are able to join VC hearing, they are required to wait patiently for their turn.

- Once joined in VC hearing room, all parties shall ensure that they keep the Mic of their devices mute. The same shall be unmuted as and when the Bench requires the party to make submissions, and shall be muted again as soon as submissions are made.

- Reply/reports/response documents etc. to be filed through e-filing well in advance, in any case, not later than 03:00 P.M. on the working day prior to the date of hearing.[40]

'NGT' as defined in Official Government Reports

186th Report on Proposal to Constitute Environmental Courts, Law Commission of India, 2003

Prompted by the Supreme Court's order in A.P. Pollution Control Board v. M.V. Rayadu,[41] the Law Commission of India issued the 186th Report, analyzing the feasibility of establishing environmental courts in India.

Some of the Commission's important recommendations were:

- There is a need to have separate ‘Environment Courts’ manned only by the persons having judicial or legal experience and assisted by persons having scientific qualification and experience in the field of environment.

- These ‘Environment Courts’ should be established and constituted by the Union Government in each State. However, in case of smaller States and Union Territories, one court for more than one State or Union Territory may serve the purpose.

- Parliament has exclusive jurisdiction to enact a law to establish 'Environmental Courts' under Entry 13 of List I of the 7th schedule.

- The proposed Court should not be bound to follow the procedure prescribed under the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 or the Indian Evidence Act, 1872, but will be guided by the principles of natural justice.

- Appeal against the orders of the proposed Environment Court, should lie before the Supreme Court on the question of facts and law. The powers of High Courts under Articles 226 and 227 and the Supreme Court under Article 32 of the Constitution of India shall not be ousted.[42]

The subsequent establishment of the National Green Tribunal in 2010 mirrored many of these proposals, and focused on addressing the unique environmental challenges in the country, marking a significant development in India's legal landscape.

203rd Report on NGT Bill, 2009, DRPSC on Science & Technology, Environment & Forests, 2009

The Departmentally-Related Parliamentary Standing Committee (DRPSC) on Science & Technology, Environment & Forests issued its report on the National Green Tribunal Bill, 2009 on 24th November, 2009. Some of its observations were:

- The applicability of the concept of 'substantial question', as defined in section 2(1)(m) of the NGT Act, 2010[43] should be decided by the NGT itself, which can evolve further through interpretation by higher courts.

- The proviso to section 21 of the NGT Act,[44] which allows the Chairperson, or another Member of the Tribunal to make a tie-breaking decision was added at the recommendation of the DRPSC.

- Section 18(2)(e) of the NGT Act,[45] which allows any aggrieved person or representative organization to file an application was added at the recommendation of the DRPSC. Earlier, only "any representative body or organization functioning in the field of environment, with permission of the Tribunal" was allowed to file applications.

- Section 20 of the NGT Act,[46] which requires the Tribunal to apply principles of sustainable development, the precautionary principle and the polluter pays principle during decision-making was also added at the recommendation of the DRPSC.[47]

Bird's eye view of NGT's performance in the last 5 years, National Green Tribunal, 2023

The National Green Tribunal published a report on Bird's eye view of NGT's performance in the last 5 years, assessing its performance from July 2018 - July 2023. Some of the important insights from this report include:

- The NGT received 15132 cases in the given period, and disposed of 16042 cases. Of this, 8419 were disposed by the Chairperson bench. Therefore, the Tribunal had a positive disposal-to-institution rate.

- The NGT adopted many institutional and administrative reforms, such as:

- Use of Video Conferencing;

- Special Bench for disposal of 5+ year old & complex cases, allowing disposal of over 275 five-year old cases;

- Independent factual reports by credible third-parties were obtained;

- Notices were served through e-mail, and all orders were placed on website;

- Suo-motu interventions, letter petitions, and interventions with Chief Secretaries of States/UTs were organized.[48]

'NGT' as defined in Case Laws

Need of specialised Environment Court

M.C. Mehta v. Union of India, 1986

In the M.C. Mehta v. Union of India case, Justice P.N. Bhagwati proposed that since cases involving issues of environmental pollution, ecological destruction and conflicts over natural resources were increasingly coming up for adjudication and these cases involved assessment and evolution of scientific and technical data, it would be desirable to set up Environment Courts on the regional basis with one professional Judge and two experts drawn from the Ecological Sciences Research Group keeping in view the nature of the case and the expertise required for its adjudication. There would of-course be a right of appeal to this Court from the decision of the Environment Court. This was the first time the SC endorsed the suggestion for an NGT-like body.[49]

A.P. Pollution Control Board v. M.V. Rayadu, 2000

A.P. Pollution Control Board v. M.V. Rayadu was the second Supreme Court case that comprehensively dealt with the demand to create separate Environmental Courts. The Court recommended that the Law Commission should examine existing environmental laws and the need for constitution of Environmental Courts with experts in environmental law, in addition to judicial members, in the light of experience in other countries. This eventually culminated in the 186th report of the Law Commission, supporting the establishment of the NGT.[50]

Ms. Betty C. Alvares v. The State of Goa, 2014

In the case of Ms. Betty C. Alvares v. The State of Goa before the National Green Tribunal, dispute arose over whether foreign citizens had the locus standi to file cases at the NGT. The Tribunal rejected arguments that only citizens could file applications, since the NGT was established to advance Article 21 of the Constitution, which affords protection to all persons, and section 2(1)(j) of the NGT Act does not make any distinction between citizens and foreigners. Therefore, the jurisdiction of the NGT was significantly enlarged.[51]

Power of Judicial Review

Wilfred J vs. Ministry of Environment & Forests, 2014

In the case of Wilfred J vs. Ministry of Environment & Forests, the National Green Tribunal held that it had the powers of judicial review to decide on the validity of subordinate legislation, and not on the validity of primary legislation. Therefore, it could overrule a CRZ Regulation issued by a state for violating the National Coastal Zone Management Authority's orders. This expanded its jurisdiction, and gave the Tribunal powers of judicial review.[52]

Jurisdictional Limit

Samir Mehta v. Union of India, 2016

In the case of Samir Mehta v. Union of India, the NGT ruled that it had jurisdiction over an incident occurring 20 nautical miles off Mumbai's coast, beyond India's territorial waters, because India had sovereignty over natural resources in contiguous areas and economic zones under the Maritime Zones Act, 1976. It held authority to address maritime pollution in these zones and to grant compensation for government expenses in cleaning wrecks, aligning with international conventions. This case also expanded the jurisdiction of the NGT, which was not confined to the boundaries of the territory of India anymore.[53]

Power of Judicial Review

Central India AYUSH Drug Manufacturers v. State of Maharashtra, 2016

In Central India AYUSH Drug Manufacturers v. State of Maharashtra, the Bombay High Court (Nagpur Bench) held that the constitutional validity of a statute or subordinate legislation could only be challenged under Article 226 and 32 of the Constitution and not before an authority which is constituted under any statute. It laid down the principle that the NGT could only deal with disputes that met each of the following criteria under section 14 of the NGT Act: the dispute must be civil in nature; it must arise out of implementation of enactments specified in Schedule-I; substantial question relating to environment must be involved. Thus, the Tribunal's jurisdiction was ousted.[54]

Suo-Motu Jurisdiction

Municipal Corporation of Bombay v. Ankita Sinha, 2021

In the case of Municipal Corporation of Bombay v. Ankita Sinha, a three-judge bench of the Supreme Court held that the NGT had the authority to take suo-motu action in some environmental matters, without being constrained by procedural requirements or formal petitions. The court held that as long as the 'sphere of action' is not breached, the NGT's powers should be interpreted liberally. The judgment aimed to address the imbalance of powers in the interest of social justice, particularly concerning environmental concerns, by expanding locus standi in public interest litigation. Therefore, the Tribunal became empowered to initiate proceedings against parties who cause environmental damage.[55]

Constitutional Challenge

M.P. High Court Advocate Bar Association v. Union of India, 2022

Lastly, in the most monumental case about NGT's jurisdiction titled M.P. High Court Advocate Bar Association v. Union of India, the Supreme Court upheld the NGT Act, and held that it was not an excessive delegation of power. Further, High Court and Supreme Court's jurisdiction under section 226 and 32 were not ousted, and they could also hear appeals from the Tribunal. Importantly, the Court also held that the establishment of NGT benches across all states is unwarranted given the current caseloads, leading to the dismissal of the petitioners' pleas for relocating the Bhopal Bench to Jabalpur.[56]

International Experience

Australia

The Land and Environment Court of New South Wales is the first specialist environmental superior court in the world. It was established on 1 September 1980 by the Land and Environment Court Act 1979. It's jurisdiction includes merits review, judicial review, civil enforcement, criminal prosecution, criminal appeals and civil claims about planning, environmental, land, mining and other legislation. Uniquely, the court has more powers than the National Green Tribunal. While NGT only has civil jurisdiction, the LEC can also declare legislation ultra vires, and start criminal prosecutions. Further, it is a 'one-stop shop' for all legislation, while the NGT does not exercise jurisdiction over laws like the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972, the Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006, or the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013.[57]

United States of America

In the United States of America, jurisdiction over environmental law disputes is exercised by an independent division of the Environment Protection Agency (EPA). Thus Administrative Law Judges (ALJ) division renders decisions in proceedings between the EPA and persons, businesses, government entities, and other organizations that are, or are alleged to be, regulated under environmental laws. Further, Alternate Dispute Resolution is permitted and encouraged. This has three key benefits:

- It allows the State (through the EPA) to be a party to environmental law disputes. Therefore, the legal burden on private actors is reduced, and criminal prosecution for Human Rights violations can be sought.

- It reduces case pendency by allowing Alternate Dispute Resolution, which is missing in the Indian NGT.[58]

Canada

Canada has a two-step environmental law adjudication mechanism. Under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999, Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) Enforcement Officers can issue Compliance Orders (like injunctions) or Administrative Monetary Penalties against private actors. Thereafter, the Environmental Protection Tribunal of Canada (EPTC) reviews these orders, and can modify them accordingly. Therefore, the EPTC is primarily an appellate body.[59] This has advantages and disadvantages in light of the NGT experience. By according first-step powers directly to officers, disposal of cases can occur speedily, and different officers can be approached in the closest jurisdiction, making them accessible. However, at the same time, according such adjudicatory powers to government officers also carries risks. An independent judicial mechanism is still required for safeguarding rights.

Chile

Chile, much like India, created special independent jurisdictional bodies, whose function is to resolve environmental disputes. Although they are not part of the Judicial Branch, they are subject to the directive, correctional and economic oversight of the Chilean Supreme Court. Presently, three Environmental Courts exist in Chile, the first of which was established in 2012. Much like the Indian NGT with different jurisdictions for each bench of sitting, these Courts also exercise jurisdiction over different zones of the country.

The Environmental Courts are mixed collegial body, meaning they are composed not only of lawyer ministers, but also of ministers with science degrees specializing in environmental matters. This allows them to incorporate a technical and specialized perspective into the legal analysis of each case, and pass better judgements. This is similar to the Indian bifurcation of Judicial and Expert Members.[60]

Kenya

Kenya has the unique distinction of being the only country in the world having a constitutional provision about a separate environmental court. Article 162(2) of the Constitution requires the establishment of the Environment and Land Court as a superior court of Kenya. It was operationalized in 2011, with the power to hear and determine disputes relating to the environment and the use and occupation of, and title to land. The court exercises jurisdiction throughout Kenya. It has original and appellate jurisdiction to hear and determine all disputes relating to environmental laws, land administration and management, public, private and community land and contracts, etc. It also exercises appellate jurisdiction over decisions of subordinate courts and local tribunals, and also acts in a supervisory capacity for them.[61]

Many of these features make the Kenya Court an aspirational standard. Prescribing its provisions in the Constitution ensures independence and safeguards the jurisdiction of the ELC. India could appropriately amend the Constitution and make the NGT a constitutional authority. Further, much like Australia, by giving the court jurisdiction over land disputes as well, the court prevents forum-shopping, and reduces the inaccessibility faced by aggrieved parties.

New Zealand

New Zealand has a long history of tribunals and commissions to review state acts for their environmental impact. In 1991, to promote sustainable management of natural and physical resources, the Resource Management Act (RMA) was passed. Later, the Environment Court was formed in 1996, with judges in three registries, who travel to other cities and towns if required.

The Environment Court is an appellate court, meaning that it can consider matters afresh. The majority of the court's work involves hearing appeals about issues that arise under the Resource Management Act 1991, with most of its workload coming from appeals brought against decisions of local authorities. These appeals are typically brought against decisions made on plan changes and policy statements and decisions made on resource consent applications. The Environment Court, much like the NGT has different places of sitting, from where judges exercise jurisdiction over the rest of the country. However, uniquely, judges can independently move to other locations to hear matters as needed, and sit and hear matters as close as possible to the location of the issues in dispute. This prevents inaccessibility, and ensures that people are not discouraged from filing appeals at the court.[62]

Sweden

In 1999, Sweden passed a comprehensive Environmental Code, which, among other things, established the Land and Environment Court. This court, guided by the Code and international economic law, can make administrative decisions and impose damages/sanctions. These Courts are attached to various District Courts, allowing a greater number of benches, equally spread across the country. There is also a Land and Environment Court of Appeal, which separately hears appeals from the LEC's decisions.

The presence of a complete Environmental Code uniquely allows all environmental law to be codified and harmonized at one place. India can also compile its 10+ statutes and various rules and regulations dealing with environmental law, some of which often have conflicting provisions, to improve the efficacy of the NGT. Further, a separation of courts which hear original applications and appeals can also improve functioning, which may be operationalized in India by instituting a special appellate bench.[63]

Technological Transformation & Initiatives

Video Conferencing

In July 2018, due to rising vacancies in the Tribunal, it began using video conferencing to speed up case hearings.[64] Later, during COVID-19, due to the government lockdown and shortage of staff, the entire Tribunal moved online, and started using "Vidyo" app to conduct hearings.[65] Now, hybrid hearings are conducted, and litigants/lawyers desirous of appearing virtually can do so, while the rest are permitted to attend physically. This has significantly improved the case disposal rate of most Benches, and allows the NGT to deal with more cases from remoter corners of the world.

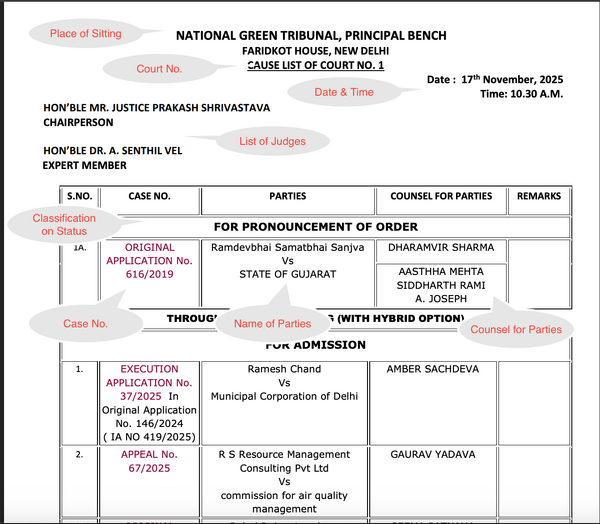

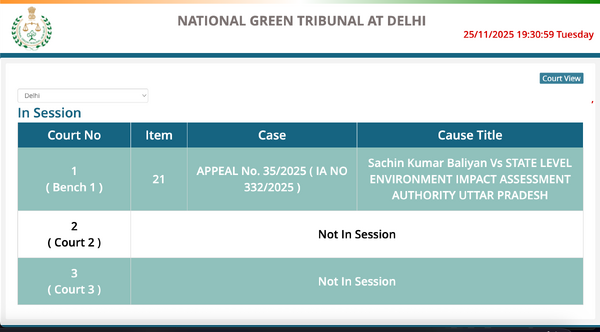

e-Cause List

The National Green Tribunal publishes daily Advance and Normal Cause Lists for each of the 4 Principal Zone benches and the Western, Eastern, Central and Southern Zone benches. Cause Lists for the Principal Bench can be found here. These cause lists include the following information:

- Judge Presiding

- Case Number

- Name of Parties

- Counsel for Parties

- Remarks

Additionally, the cause lists are divided by the stage of proceeding. Therefore, cases are classified, depending on whether they are "For Admission", "After Notice", "For Pronouncement of Order", etc. Further, the Cause List also provides the meeting links for joining the proceedings via Webex, as well as Office Orders that outline the protocol for such hybrid hearings.

e-Filing

The National Green Tribunal also allows litigants to file applications, appeals, Intervention Applications, caveats, rejoinders, and other relevant documents entirely online. Court fees and printing charges are also paid virtually. Therefore, the court has become relative "paperless", in line with the Supreme Court's initiative for reducing wastage.

The process for e-filing is relatively straightforward, and requires parties to click on "Applicant's Corner" at: https://ngtonline.nic.in/efiling/mainPage.drt. To understand further steps, parties can also use the official User Manual for the e-Filing Module of the NGT, which can be accessed at: https://ngtonline.nic.in/efiling/viewUserManualDoc.drt.

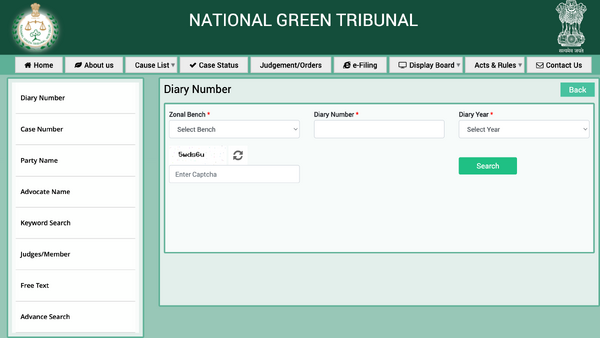

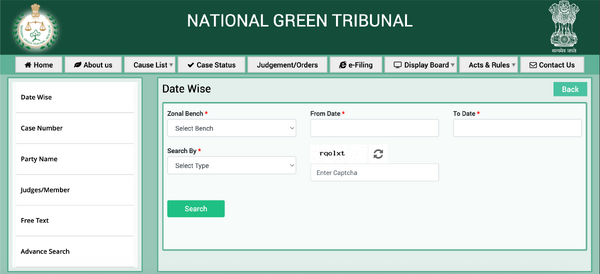

e-Case Status, Judgement/Order & Display Board

Apart from allowing litigants to file applications and view cause lists online, the NGT website also displays the live Case Status, Judgements/Orders and Display Board from the Courts.

Parties can actively view their Case Status by using the following link: https://www.greentribunal.gov.in/casestatus/diarynumber. It allows viewing the case status based on Diary Number, Case Number, Party Name, Advocate Name, Keyword Search, and Judges/Member.

The public can access any Judgement or Order passed by the National Green Tribunal using the following link: https://www.greentribunal.gov.in/judgementOrder/zonalbenchwise. Thereafter, they can choose to access the judgement Date Wise, Case Number Wise, Party Name Wise, or Judges/Member Wise, depending on what information is available to them.

Apart from this, the Tribunal also has a live Display Board, where litigants/lawyers can keep track of when their case might be called next. It can be accessed by clicking on "Display Board" on the NGT website, then clicking "National Green Tribunal", and then selecting the appropriate bench. The link for the Principal Bench in New Delhi is available here: https://e-commcourt.gov.in/dashboard/showallcourtcases.

Appearance of National Green Tribunal in Databases

The National Green Tribunal's performance at disposing cases has been mixed. From 2018-2023, the NGT's disposal rate was higher than the case institution rate. Therefore, pendency was rapidly declining.[48] However, since then, there has been a rise of cases again, with over 5000+ cases pending across the 5 benches presently.

| Bench | Pendency |

|---|---|

| New Delhi (Principal, North Zone) | 1888 |

| Chennai (South Zone) | 811 |

| Bhopal (Central Zone) | 306 |

| Pune (Western Zone) | 1904 |

| Kolkata (Eastern Zone) | 392 |

| (Total) | 5301 |

To deal with pendency, the NGT has taken various initiatives in the past. Video conferencing has been permanently introduced since 2018, allowing parties to appear online.[64] In 2023, there was a special drive to take up more than five year old cases/ other cases of complex nature. This also resulted in disposal of long pending cases due to which some public projects were held up. 275 cases older than five years old cases stood disposed as of 2023.[48]

Institution and disposal rates throughout the years have also varied. In the first two years, only a few hundred cases was filed. Thereafter, the number increased exponentially, and regularly averages around 4000 now. However, during COVID-19, there was a significant decline to approximately 2000 cases filed. The number of cases instituted and disposed by year, from 2011-2022, obtained from Parliamentary questions and the Ministry of Environment, Forests, and Climate Change Annual Reports is as follows:

| Year | Institution | Disposal |

|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 168 | 163 |

| 2012 | 548 | 438 |

| 2013 | 3116 | 1585[66] |

| 2014 | 2791 | 1861 |

| 2015 | 5478 | 4815 |

| 2016 | 5812 | 6798 |

| 2017 | 6353 | 5615[67] |

| 2018 | 4079 | 3716 |

| 2019 | 3269 | 3323 |

| 2020 | 2301 | 2610 |

| 2021 | 2381 | 2600 |

| 2022 | 3170 | 3497[68] |

Centre for Environmental Law, WWF India Database (2011-19)

The National Green Tribunal also appears in the World Wide Fund for Nature - India (WWF India)'s Centre for Environmental Law research. By analyzing all judgements/orders passed by the NGT from 2011 to 2019, the Centre shows the distribution of these cases across various sectors. While this research is definitely outdated, it sheds important light on the NGT's role in moderating various industries.[69]

Further, the Centre for Environmental Law also maintains Case Summaries for every application/appeal filed at the NGT from 2011 to 2021. They can be accessed at: https://www.wwfindia.org/about_wwf/enablers/cel/national_green_tribunal/case_summaries/.

Research that engages with National Green Tribunal

Assessing the National Green Tribunal after Four Years, 2014

Dr. Armin Rosencranz and Geetanjoy Sahu, researchers of environmental law wrote an article in the Journal of Indian Law and Society (WBNUJS, Kolkata), 5th Volume, assessing the performance of the NGT four years after its establishment. They argued that the NGT had been progressive in its approach, especially towards marginalized people. They also made recommendations to strengthen the NGT framework, by laying down concrete guidelines for exercise of powers and execution of their decisions by the executive. They also recommended scrutinizing and reviewing petitions and investigating the intentions of petitioners, in order to prevent frivolous applications. Further, while exhaustively assessing judgements of the NGT, they pointed out how the regional benches of the Tribunal were more aggressive than the Principal Bench, owing to the lack of ambition for Central Government positions. However, the authors also ended on a gloomy note, arguing that recent attempts to water down the powers and jurisdiction of the NGT would pose serious challenges, and could hamper its ability to shape environmental law in the country.[70]

Impact of the NGT on Environmental Governance in India, 2016

Dr. Geetanjoy Sahu wrote another article for the Journal for Environmental Law, Policy & Development (NLSIU), Volume 3, titled "Impact of the NGT on Environmental Governance in India: An Analysis of Methods & Perspectives". The author argued that the NGT has not only come down heavily against micro-structures such as urban and rural local bodies but has also challenged the big corporate sectors and the central and state governments for not following environmental regulations. Further, the NGT, through its interpretations, has made an attempt to reconcile different claims on behalf of development, environmental protection and human rights, holding that development activities which address the increasing demands of the people need to be carried out without unduly straining the available resources. They also argue that the court's decision-making apparatus is clearly innovative. For example, if parties do not have the locus standi to bring a case to the Tribunal, they have expanded the definition of "aggrieved person" under the NGT Act. Similarly, "monitoring committees" have been set up, to ensure compliance with the Tribunal's decisions. Overall, the author takes a positive view of the NGT.[71]

Evaluating the National Green Tribunal after Nearly a Decade (NLIU Law Review, 2020)

Raghuveer Nath Dixit, a corporate lawyer and Dr. Armin Rosencranz, a Professor of Law & Public Policy wrote an article titled "Evaluating the National Green Tribunal after Nearly a Decade: Ten Challenges to Overcome" in the NLIU Law Review, IX Volume. Like its name suggests, the article pointed to 10 challenges that were preventing effective functioning of the NGT. These were:

- Challenge to Suo Motu Jurisdiction: The authors pointed to recent decisions by High Courts barring suo-motu action by the NGT, arguing that the Tribunal was not a substitute for Courts. This hindered effective public interest protection. It is pertinent to note that subsequent to the publication of this article, the Supreme Court explicitly recognized the NGT's suo-motu jurisdiction.

- Frequent Appeals to High Court: Different courts have given varied decisions on the ability of High Courts to take appeals from decisions of the NGT. While the Act explicitly provides for appeals directly to the Supreme Court, relying on a judgement that their Article 226 jurisdiction cannot be ousted, some High Courts have asserted their jurisdiction. This causes unnecessary delays and costs on litigants.

- Non-Scientific Determination of Compensation: The NGT, without the absence of specific guidelines for determining compensation, has followed a principle where 5-10% of the project cost is levied as compensation. However, this amount being extremely low, it is likely to allow potential polluters to do a cost-benefit analysis before undertaking a project. Therefore, there is need for scientific determination of environmental damage, to which compensation must be pegged.

- Trend of not Penalizing Government Authorities: The authors have also argued that the NGT has shown a lackadaisical attitude towards violation by government entities, often imposing little-to-no damages for flagrant violations. It is recommended that high costs may be imposed to deter arbitrary action.

- Inadequate Implementation of Decisions: The NGT Act, despite clear recommendations by the Law Commission and DRPSC, has no explicit power to hold parties in contempt. This prevents it from effectively enforcing its decisions by recalcitrant parties. Further, despite a requirement for damages to be transferred to the Environmental Relief Fund, the Tribunal itself seems to impose other manners of payment. Therefore, there is no uniform implementation mechanism.

- Dilution of NGT’s Independence through Amendments to the Finance Act, 2017: The unceremonious ouster of independence by the Finance Act, 2017, which provides that appointment of Members shall be governed by Rules, allows the Central Government to install political actors as Members. It is important to note that the Supreme Court's decision in Rojer Mathew v South Indian Bank Ltd. declared these sections of the Finance Act ultra vires, thereby restoring the status quo.[72]

- Lack of Basic Amenities & Infrastructure: The authors also pointed to the lack of infrastructure available at all of the NGT benches, hampering their functioning. However, as the authors pointed out, the Supreme Court's firm directions to immediately provide "dignity" and improve the NGT's facilities has brought positive change.

- Lack of Access to Justice: The authors also argued that the 5-bench approach that the NGT was following, with places of sitting in Delhi, Kolkata, Pune, Bhopal, Chennai prevented litigation from remote and inaccessible areas. Despite the provision for e-filing and video conferencing, lawyers and litigants were hesitant. It was recommended that local district courts connect parties via video conferencing, to ensure comfort.

- Delays & Conflicts of Interest in Appointment: The authors also pointed out the delays in appointment of members to the NGT, which has rarely met the minimum 20 member criteria laid down by the NGT Act, 2010. Further, the increasing appointment of bureaucrats as Expert Members was criticized for lack of domain expertise.

- Tussle with MoEF&CC: The authors argue that the Ministry of Environment, Forests, and Climate Change generally maintain an apathetic and adversarial approach with the NGT, which was established due to the push of the Supreme Court. This relationship causes further government hurdles, like the slashing of NGT's budget or appointment dilution.[73]

A Tribunal in Trouble? (CEERA NLSIU, 2020)

Dr. Sairam Bhat, Professor of Law at NLSIU, and Lianne D’Souza wrote an article in the Journal of Environmental Law, Policy & Development, Volume 7 for the Centre for Environmental Law, Education, Research and Advocacy (CEERA), arguing that the NGT's powers were getting significantly diluted. They pointed out various institutional flaws, some of which are included below:

- Judicial & Administrative Fallacies: The NGT's decisions often contained flawed reasoning, and undermined principles of strict liability laid down in landmark Supreme Court judgements. Further, ministerial attempts to transfer cases, shortage of manpower, limited number of benches, and high vacancies prevent effective functioning.

- Conflict with High Courts: The authors argue that the NGT's scope, as per the NGT Act is at par with High Courts, except their writ jurisdiction, since appeals lie directly to High Courts. However, various High Courts have used their plenary jurisdiction to take over cases, causing duplicitous avenues for redress.

- Jurisdictional Limitations: The pre-requisite for cases to involve a substantial question of environment limit the NGT's jurisdiction. Further, Court's decisions striking down NGT orders on "academic questions" or subordinate legislation have also diluted the Tribunal's ability.

- Scope of Judicial Review: Similarly, Court decisions have continuously held that the NGT is not empowered to determine the vires of statutes or subordinate legislation, which prevents the NGT's ability to decide 'all' matters related to the environment.[74]

Mapping the Power Struggles of the NGT of India: The Rise and Fall? (AJLS,2020)

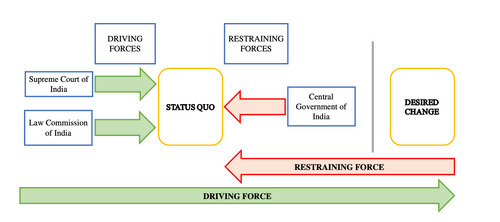

Gitanjali Nain Gill wrote an article titled "Mapping the Power Struggles of the National Green Tribunal of India: The Rise and Fall?" for the Asian Journal of Law & Society (Cambridge University Press), Volume 7, applying Kurt Lewin and Edgar Schein's change management theory. They argue that the establishment of NGT starts with an Unfreeze Stage, where the Supreme Court acts as a driving force, while the Central Government acted as resistant force. Thereafter, a Move Stage occurs, where the Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change backs the NGT, and supports changes. However, some time later, a Refreeze Stage also occurs, as the NGT gains public confidence, but locks horns with the Central Government and its projects. Eventually, this results in powerful negative forces, that cause a thawing, and the cycle of change restarts. This is prompted by resistance from the Central Government, High Courts, and other actors. This theory argues that the NGT, in its current phase, may fall victim to structural constraints like its predecessor National Environmental Appellate Authority (NEAA), unless vacancies are filled and the resisting forces renew their support for the Tribunal.[75]

The Role of National Green Tribunal in Environmental Protection (IJES, 2025)

Dr. Nagesh Sadanand Colvalkar wrote an article in the International Journal of Environmental Sciences, Volume 11, where he provided a critical perspective to the role of the NGT in environmental protection. The author questioned the enforcement ability of NGT's orders, coordination with regulatory authorities, and the long-term sustainability of its interventions in a rapidly industrializing economy. By systematically evaluating both its successes and shortcomings, he argued that the NGT emerged as a vital but evolving institution whose credibility rests on its ability to adapt to new environmental challenges while ensuring impartiality, transparency, and timely justice. He concluded that while the NGT alone cannot resolve India’s environmental crises, its presence significantly strengthens the rule of environmental law. The author also made recommendations for expanding NGT's jurisdictional reach, and fostering stronger inter-institutional linkages between the Tribunal, government, and Constitutional Courts.[76]

Efficiency at the NGT & Its Accessibility: An Empirical Study

In a forthcoming publication, Dr. Madhuker Sharma performed an empirical analysis into the following hypotheses:

- Executive Failure in Ensuring Minimum Strength: Under the NGT Act and relevant rules, the Central Government is required to appoint 20 Judicial and 20 Expert Members to the Tribunal. The author argues that over 1/3rd of Judicial Member seats and 1/4th of Expert Member seats have gone vacant since the establishment of the NGT, despite the presence of many retired judges and experts.

- NGT's Success at Legal Mandate: The NGT Act imposes an obligation on the Tribunal to dispose of a case within 6 months of its institution. According to the author, it has been largely successful at this goal, considering the low pendency rate. However, they point out that this occurs due to the less number of disputes that reach the Tribunal in the first place.

- Executive Failure in Accessibility: The author argues that the 700 km+ distance between the last state under a Bench's jurisdiction causes inaccessibility. Thus, distance of the subject from the place where Bench of the Tribunal is situated matters a lot. It is concluded that breaking down the barrier of distance will increase possibility of more victims approaching the Tribunal, which would be desirable.[77]

Issues and Challenges

Vacancies & Delayed Appointment

As various reports have pointed out, the most onerous problem that plagues the functioning of the National Green Tribunal is vacancies.[78][79] Against a sanctioned strength of 20 Judicial Members and 20 Expert Members, only 4 Judicial Members and 6 Expert Members serve on the NGT, as of November 2025.[80][81] In fact, throughout the history of NGT, it has never functioned at full capacity. Coupled with the National Green Tribunal Act's provision that ordinary benches must be composed of at least 1 Judicial Member and 1 Expert Member, this renders many Zonal Places of Sitting defunct. The NGT Act, when it was formed, planned an ouster of jurisdiction of over 13000+ courts in India. Granting such a high burden to 10 members, without appropriate infrastructure prevents timely disposal of cases. However, the reason for such incessant vacancies is not a lack of applications. Since many High Court judges retire each year, it is prudent that many applicants exist. Yet, the Central Government has failed to appoint them, hindering the NGT's performance.

Limited Jurisdiction

The NGT's jurisdiction has also come under review in recent times. As many authors have pointed out, various High Courts have taken objection to the NGT's attempts to gain powers of judicial review. Judgements that strike down subordinate legislation have often been overturned by High Courts, despite the Supreme Court's shield.[82] Since the NGT is envisioned as a shield for all environmental law matters, inability to declare laws void hampers its ability to secure its mandate, especially since a majority of litigation in India involves the state as a party.

Further, the NGT has not been given jurisdiction over disputes arising out of the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972, the Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006, and the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013 as part of the Schedule I of the NGT Act. This fractures environmental law disputes to various forums, and prevents the emergence of the NGT as a "one stop shop" for environmental concerns, like its international counterparts.

Turf War

The NGT is frequently involved in a turf war with High Courts as well. Since the Supreme Court ruled in M.P. High Court Advocate Bar Association v. Union of India that the NGT Act does not oust the writ jurisdiction of Constitutional Courts under articles 32 and 226 of the Constitution, there have been increasing attempts by High Courts to rule on environmental law disputes themselves.[83] Not only does this hinder the ability of the NGT to develop comprehensive jurisprudence related to environmental protections, but, it also leads to flawed decisions, since High Courts do not have Expert Members to undertake hyper-technical review of the subject matter of these cases.

Inaccessibility

Further, as many scholars have pointed out, while the NGT Act has a novel provision allowing "places of sitting" or benches to be established at multiple locations, this has not been effectively utilized. Present benches in New Delhi, Pune, Bhopal, Chennai, Kolkata are often unable to serve the needs of rural or tribal regions, and prevent various infarctions from being sanctioned. While the NGT has introduced video conferencing, it does not address the root problem of inaccessibility, since most litigants (especially those with lower education) feel uncomfortable using such tools.

Further, rule 12 of the NGT (Practice and Procedure) Rules, 2011 require the payment of 1% of the amount of compensation claimed as fees while filing an application.[84] The only exemption provided is for those who are below the poverty line (BPL). However, since a large amount of the Indian population, despite not lying BPL, are clearly unable to afford such exorbitant fees. They are also deterred from claiming a large amount of compensation due to inability to pay the requisite fee. A lower, flat fee should ideally be imposed, since the work required to be discharged by the Tribunal is the same throughout cases.

Inadequate Implementation

The 186th Law Commission report and 203rd Departmentally Related Parliamentary Standing Committee report both recommended granting powers to hold parties in contempt to the NGT.[85][86] Despite this, no equivalent provision was enacted. As a result, the only way to enforce decisions is through starting separate criminal proceedings under section 26 of the NGT Act, which provides for imprisonment for 3 years and fine up to Rs. 10 crore for contravention of NGT's directions.[87] However, since the NGT cannot enforce such punishment itself, persons are free to act in impunity of the Tribunal's decision, and seek a defense at the court considering the criminal case later.

Way Forward

While the National Green Tribunal is a novel mechanism, some reforms are urgently required. The Central Government should ensure all vacancies are filled, by making appointments at regular intervals. The NGT Act should include explicit provisions clarifying the jurisdiction of the court, the appeal mechanism (and whether it intends to exclude High Courts), as well as the need for High Courts to transfer cases to NGT where appropriate. Further, more benches should be established, or, local district courts should install necessary infrastructure to support video conferencing with the present 5 benches from a more familiar location. Lastly, the independence of the NGT should be improved, by reducing the antagonism between the Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change and the NGT.

References

- ↑ The National Green Tribunal Act, 2010, s. 3, available at https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/2025/1/AA2010__19green.pdf

- ↑ S.O. 2569 (E), 18.10.2010, available at https://upload.indiacode.nic.in/showfile?actid=AC_CEN_16_18_00009_201019_1517807326004&type=notification&filename=s.o._2569_(e),_dated_18_10_2010_-_appointment_of_shri_justice_l.s._panta_former_judge_of_the_supreme_court_as_chairperson_of_the_ngt.pdf

- ↑ The National Green Tribunal Act, 2010, s. 4(3), available at https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/2025/1/AA2010__19green.pdf

- ↑ S.O. 1908 (E), 17.08.2011, available at https://upload.indiacode.nic.in/showfile?actid=AC_CEN_16_18_00009_201019_1517807326004&type=notification&filename=s.o._1908_(e),_%5B17_08_2011%5D_-_various_ordinary_places_of_sitting_of_the_natiional_green_tribunal_including_the_territorial_jurisdiction.pdf

- ↑ 2022 INSC 586, available at https://api.sci.gov.in/supremecourt/2012/32486/32486_2012_9_1501_35976_Judgement_18-May-2022.pdf.

- ↑ The National Green Tribunal Act, 2010, s. 2(1)(n), available at https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/2025/1/AA2010__19green.pdf.

- ↑ The National Green Tribunal Act, 2010, s. 3, available at https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/2025/1/AA2010__19green.pdf

- ↑ S.O. 2569 (E), 18.10.2010, available at https://upload.indiacode.nic.in/showfile?actid=AC_CEN_16_18_00009_201019_1517807326004&type=notification&filename=s.o._2569_(e),_dated_18_10_2010_-_appointment_of_shri_justice_l.s._panta_former_judge_of_the_supreme_court_as_chairperson_of_the_ngt.pdf

- ↑ S.O. 2570 (E), 18.10.2010, available at https://upload.indiacode.nic.in/showfile?actid=AC_CEN_16_18_00009_201019_1517807326004&type=notification&filename=s.o._2569_(e),_dated_18_10_2010_-_appointment_of_shri_justice_l.s._panta_former_judge_of_the_supreme_court_as_chairperson_of_the_ngt.pdf

- ↑ The National Green Tribunal Act, 2010, s. 14, 16, available at https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/2025/1/AA2010__19green.pdf

- ↑ The National Green Tribunal, 2010, First Schedule, available athttps://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/2025/1/AA2010__19green.pdf

- ↑ National Green Tribunal, 'About Us', available at https://greentribunal.in/about-us.php

- ↑ S.O. 1003 (E), 05.05.2011, available at https://upload.indiacode.nic.in/showfile?actid=AC_CEN_16_18_00009_201019_1517807326004&type=notification&filename=s.o._1003(e),_dated_05_05_2011_-_specifying_delhi_as_the_ordinary_place_of_sitting_of_the_national_green_tribunal.pdf

- ↑ S.O. 1908 (E), 17.08.2011, available at https://www.greentribunal.gov.in/sites/default/files/all_documents/Order%20dated%2028.02.20_0.PDF

- ↑ The National Green Tribunal Act, 2010, s. 3, available at https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/2025/1/AA2010__19green.pdf

- ↑ The National Green Tribunal Act, 2010, s. 3, available at https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/2025/1/AA2010__19green.pdf

- ↑ Press Information Bureau, Press Release, 05.11.2011, available at https://www.pib.gov.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=75516.

- ↑ The National Green Tribunal Act, 2010, s. 6(2), available at https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/2025/1/AA2010__19green.pdf.

- ↑ National Green Tribunal (Manner of Appointment of Judicial and Expert Members, Salaries, Allowances and otherTerms and Conditions of Service of Chairperson and other Members and Procedure for Inquiry) Rules, 2010, available at https://upload.indiacode.nic.in/showfile?actid=AC_CEN_16_18_00009_201019_1517807326004&type=rule&filename=gsr_927_(e),_dated_26_11_2010_-_national_green_tribunal.pdf.

- ↑ The National Green Tribunal Act, 2010, s. 7, available at https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/2025/1/AA2010__19green.pdf

- ↑ The National Green Tribunal Act, 2010, s. 9, available at https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/2025/1/AA2010__19green.pdf

- ↑ The National Green Tribunal (Manner of Appointment of Judicial and Expert Members Salaries, Allowances and other Terms and Conditions of Service of Chairperson and other Members and Procedure for Inquiry) Rules, 2010, rule 7, available athttps://upload.indiacode.nic.in/showfile?actid=AC_CEN_16_18_00009_201019_1517807326004&type=rule&filename=gsr_927_(e),_dated_26_11_2010_-_national_green_tribunal.pdf

- ↑ The National Green Tribunal Act, 2010, s. 8, available at https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/2025/1/AA2010__19green.pdf

- ↑ The National Green Tribunal Act, 2010, s. 10, available at https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/2025/1/AA2010__19green.pdf

- ↑ The National Green Tribunal (Manner of Appointment of Judicial and Expert Members Salaries, Allowances and other Terms and Conditions of Service of Chairperson and other Members and Procedure for Inquiry) Rules, 2010, rules 19, 20, 21, available athttps://upload.indiacode.nic.in/showfile?actid=AC_CEN_16_18_00009_201019_1517807326004&type=rule&filename=gsr_927_(e),_dated_26_11_2010_-_national_green_tribunal.pdf

- ↑ The National Green Tribunal Act, 2010, s. 4(4), available athttps://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/2025/1/AA2010__19green.pdf

- ↑ The National Green Tribunal (Practices and Procedure) Rules, 2011, rule 3, available at https://upload.indiacode.nic.in/showfile?actid=AC_CEN_16_18_00009_201019_1517807326004&type=rule&filename=gsr_296_(e),_dated_04_04_2011_-_ngt_(practice_and_procedure)_rules,_2011.pdf

- ↑ The National Green Tribunal (Practice and Procedure) Rules, 2011, rules 7, 8, 9, 10, available at https://upload.indiacode.nic.in/showfile?actid=AC_CEN_16_18_00009_201019_1517807326004&type=rule&filename=gsr_296_(e),_dated_04_04_2011_-_ngt_(practice_and_procedure)_rules,_2011.pdf

- ↑ The National Green Tribunal Act, 2010, s. 19, available at https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/2025/1/AA2010__19green.pdf

- ↑ The National Green Tribunal (Practice & Procedure) Rules, 2011, rule 21, available at https://upload.indiacode.nic.in/showfile?actid=AC_CEN_16_18_00009_201019_1517807326004&type=rule&filename=gsr_296_(e),_dated_04_04_2011_-_ngt_(practice_and_procedure)_rules,_2011.pdf

- ↑ UNFCC, 'The Rio Conventions', available at https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-rio-conventions

- ↑ United Nations Sustainable Development, 'Agenda 21', p 8.18, available athttps://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/Agenda21.pdf?_gl=1*oge5m4*_ga*Nzc4MjgzMjE2LjE3NjE4NDEyNTY.*_ga_TK9BQL5X7Z*czE3NjM5ODU1MzkkbzIkZzEkdDE3NjM5ODczNzMkajYwJGwwJGgw

- ↑ The National Green Tribunal Act, 2010, Preamble, available at https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/2025/1/AA2010__19green.pdf

- ↑ UN Environment Programme, 'Environmental Courts & Tribunals', 2016, p. 34, available at https://wedocs.unep.org/rest/api/core/bitstreams/15842456-81f3-4941-9d3b-7c5020e23a72/content

- ↑ UN Environment Programme, 'Environmental Courts & Tribunals', 2016, pp. 71-72, available at https://wedocs.unep.org/rest/api/core/bitstreams/15842456-81f3-4941-9d3b-7c5020e23a72/content

- ↑ UN Environment Programme, 'Environmental Courts & Tribunals', 2021, p. 28, available at https://www.unep.org/resources/publication/environmental-courts-and-tribunals-2021-guide-policy-makers

- ↑ UN Environment Programme, 'Environmental Courts & Tribunals', 2021, p. 98, available at https://www.unep.org/resources/publication/environmental-courts-and-tribunals-2021-guide-policy-makers

- ↑ National Green Tribunal, Office Order No. NGT(PB)/DR/2018-19/68/570, available at https://www.greentribunal.gov.in/sites/default/files/office_orders/The_Court_Proceedings.pdf.

- ↑ National Green Tribunal, Notice, available at https://www.greentribunal.gov.in/sites/default/files/office_orders/Notice%20dated%2009.07.2021.pdf.

- ↑ National Green Tribunal, Office Order No. NGT (PB)/Judicial/16/2020/390, available at https://www.greentribunal.gov.in/sites/default/files/office_orders/final.pdf.

- ↑ 1999 INSC 24.

- ↑ Law Commission of India, Proposal to Constitute Environmental Courts (Report No 186, 2003), pp. 164-168, available at https://prsindia.org/files/bills_acts/bills_parliament/2009/Proposal_to_Constitute_Environments_Courts.pdf

- ↑ The National Green Tribunal Act, 2010, s. 2(1)(m), available at https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/2025/1/AA2010__19green.pdf

- ↑ The National Green Tribunal Act, 2010, s. 21, available at https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/2025/1/AA2010__19green.pdf

- ↑ The National Green Tribunal Act, 2010, s. 18(2)(e), available at https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/2025/1/AA2010__19green.pdf

- ↑ The National Green Tribunal Act, 2010, s. 20, available at https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/2025/1/AA2010__19green.pdf

- ↑ Departmentally-Related Parliamentary Standing Committee on Science & Technology, Forests & Climate Change, The National Green Tribunal Bill, 2009 (Report No 203, 2009), para 8, available at https://prsindia.org/files/bills_acts/bills_parliament/2009/SCR_Green_Tribunal_Bill_2009.pdf

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 National Green Tribunal, Bird's eye view of NGT performance in the last 5 years, 2023, available at https://www.greentribunal.gov.in/sites/default/files/important_orders/NGT_Initiatives%20final-1.pdf

- ↑ 1987 AIR 965.

- ↑ 1999 INSC 24.

- ↑ Misc. Application No. 32/2014.

- ↑ Misc. Application No. 182/2014.

- ↑ 2016 SCCOnline NGT 479.

- ↑ 2016 SCCOnline BOM 8813.

- ↑ AIRONLINE 2021 SC 861.

- ↑ 2022 INSC 585.

- ↑ Land and Environment Court of NSW, About Us, available at https://lec.nsw.gov.au/about-us.html

- ↑ Environment Protection Agency, Administrative Law Judges, available at https://www.epa.gov/aboutepa/administrative-law-judges

- ↑ Environmental Protection Tribunal, About the Tribunal, available at https://www.eptc-tpec.gc.ca/en/about/about-eptc.html

- ↑ Environmental Court, Who we Are, available at https://tribunalambiental.cl/quienes-somos/

- ↑ Judiciary of Kenya, Environment and Land Court, available at https://judiciary.go.ke/environment-and-land-court/

- ↑ Environment Court, About, available at https://www.environmentcourt.govt.nz/about/

- ↑ Sveriges Domstolar, Land and Environment Courts, available at https://www.domstol.se/hitta-domstol/mark--och-miljodomstolar/

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 Shinjini Ghosh, 'NGT to hear pleas via videoconference', 13.07.2018, available at https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/ngt-to-hear-pleas-via-videoconference/article24414248.ece

- ↑ Akshita Saxena, 'NGT To Continue Hearing Via Video Conferencing Post Lockdown; Issues Instructions [Read Office Order]', 28.04.2020, available at https://www.livelaw.in/news-updates/ngt-to-continue-hearing-via-video-conferencing-post-lockdown-issues-instructions-read-office-order-155893

- ↑ Lok Sabha, Starred Question 289, available at https://sansad.in/ls/questions/view-question?ls=15&session=13&qno=289&type=STARRED

- ↑ Lok Sabha, Unstarred Question 3070, available at https://sansad.in/getFile/loksabhaquestions/annex/13/AU3070.pdf?source=pqals

- ↑ Lok Sabha, Unstarred Question 2804, available at https://sansad.in/getFile/loksabhaquestions/annex/1712/AU2804.pdf?source=pqals

- ↑ WWF India, Green Tribunal, available at https://www.wwfindia.org/about_wwf/enablers/cel/national_green_tribunal/

- ↑ Armin Rosencranz and Geetanjoy Sahu, 'Assessing the National Green Tribunal after Four Years', (2014) JILS 5 Monsoon, available at https://pure.jgu.edu.in/id/eprint/2412/1/Sahu2014.pdf.

- ↑ Geetanjoy Sahu, 'Impact of the National Green Tribunal on Environmental Governance in India: An Analysis of Methods and Perspectives' (2016) JELPD 3, available at https://ceerapub.nls.ac.in/journal-of-environmental-law-policy-and-development-vol-3-2016/.

- ↑ AIRONLINE 2019 SC 1514.

- ↑ Raghuveer Nath Dixit and Armin Rosencranz, 'Evaluating the National Green Tribunal after Nearly a Decade: Ten Challenges to Overcome' (2020) NLIULR 9, available at https://nliulawreview.nliu.ac.in/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Volume-IX-Issue-I-17-55.pdf.

- ↑ Sairam Bhat and Lianne D’Souza, 'A Tribunal in Trouble?' (2020) JELPD 7, available at https://ceerapub.nls.ac.in/journal-on-environmental-law-policy-and-development-vol-7-2020/.

- ↑ Gitanjali Nain Gill, 'Mapping the Power Struggles of the National Green Tribunal of India: The Rise and Fall?' (2020) AJLS 7, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/CB60FE6258D273938062A5898BD997B7/S2052901518000281a.pdf/mapping-the-power-struggles-of-the-national-green-tribunal-of-india-the-rise-and-fall.pdf.

- ↑ Nagesh Sadanand Colvalkar, 'The Role of National Green Tribunal in Environmental Protection: A Critical Review' (2025) IJES 11, available at https://theaspd.com/index.php/ijes/article/view/8078/5830.

- ↑ Madhuker Sharma, 'EFFICIENCY AT THE NATIONAL GREEN TRIBUNAL AND ITS ACCESSIBILITY: AN EMPIRICAL STUDY', available at https://www.hpnlu.ac.in/PDF/9ecadc55-2c46-48e3-87ba-4ab07b48c29b.pdf.

- ↑ Raghuveer Nath Dixit and Armin Rosencranz, 'Evaluating the National Green Tribunal after Nearly a Decade: Ten Challenges to Overcome' (2020) NLIULR 9, available at https://nliulawreview.nliu.ac.in/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Volume-IX-Issue-I-17-55.pdf.

- ↑ Sairam Bhat and Lianne D’Souza, 'A Tribunal in Trouble?' (2020) CEERA, available at https://ceerapub.nls.ac.in/a-tribunal-in-trouble/.