National Judicial Data Grid

What is the National Judicial Data Grid?

The National Judicial Data Grid (NJDG) is a nationwide digital platform that consolidates judicial case data from courts across India into a single, publicly accessible system. It functions as a comprehensive database that captures information on both pending and disposed cases from District and Taluka Courts as well as High Courts. The data available on NJDG is updated on a real-time basis through daily inputs made by courts using the e-Courts Case Information System, ensuring that the statistics reflect the current functioning of the judiciary.

NJDG was developed as part of the e-Courts project of the Supreme Court of India with the objective of improving transparency, efficiency, and accountability within the judicial system. By presenting aggregated statistics on case pendency, age of cases, stages of proceedings, and disposal patterns, NJDG enables judges, court administrators, policymakers, researchers, and the public to assess how courts are performing at the national, state, district, and individual court levels.

Official Definition of NJDG:

Evolution of the NJDG

The National Judicial Data Grid (NJDG) grew out of a practical problem that had long affected judicial administration in India: the absence of reliable, consolidated, and comparable data on court functioning. Before NJDG, information on case institution, pendency, and disposal existed largely within individual courts or states, often in incompatible formats. This made it difficult to assess systemic delays, compare performance across courts, or undertake meaningful empirical research. Developed under the eCourts Project and overseen by the Supreme Court’s eCommittee, NJDG was conceived as a way to bring together data generated through the Case Information System (CIS) into a single, continuously updated national platform.[1]

NJDG was first made publicly accessible in September 2015, beginning with district courts. This initial version was relatively modest in scope. It focused mainly on headline figures such as total pendency, case institution, and disposals. Despite these limitations, the launch was a significant institutional step. For the first time, district court data across states was presented in a standardized, publicly accessible format. The emphasis on district courts was deliberate: they account for the vast majority of litigation in India and represent the first point of contact for most litigants. In this sense, NJDG’s early design reflected concerns about access to justice and the everyday functioning of the lower judiciary.[2]

A major shift occurred in July 2020, when High Courts were brought within the NJDG framework. This expansion changed the character of the platform. With appellate data now included, NJDG moved beyond basic pendency tracking and began to support comparative analysis across courts and benches. The High Courts NJDG introduced finer classifications such as stage-wise pendency, age-based categories, and bench-level data that made it possible to identify patterns of delay and variation that were previously difficult to see. At this stage, NJDG started to function more clearly as an administrative and planning tool, rather than merely a transparency initiative.[3]

The integration of Supreme Court data in September 2023 completed NJDG’s three-tier structure. With this addition, the platform began to reflect the full trajectory of litigation, from institution in the trial courts to final adjudication at the apex level. The Supreme Court NJDG introduced features such as coram-wise pendency and time-to-disposal metrics, allowing a more detailed view of how cases move through the Court. This phase marked NJDG’s transition into a mature judicial data system, capable of supporting both internal court administration and external research on judicial performance.[4]

NJDG as Defined in official document(s)

The National Judicial Data Grid is formally defined in multiple official documents. According to the Department of Justice, Ministry of Law and Justice, the NJDG is a database of orders, judgements and case details from 18,736 District and Subordinate Courts and High Courts.[5] It is a flagship project under the e - Committee, Supreme court of India, and is a system for monitoring pendency and disposal of cases in courts. [6]This portal has been developed around the Concept of elastic search technology leading to effective management, monitoring and disposal of cases.[7]

The Judicial Statistics Bill, 2004

Fali S. Nariman’s Judicial Statistics Bill[8] was an early and important attempt to address a basic but long-ignored problem in India’s justice system, the lack of reliable data about how courts actually function. Introduced as a Private Member’s Bill in the Rajya Sabha in 2004, it proposed a structured mechanism to collect and publish statistics on case filings, pendency, disposals, and delays across all levels of the judiciary. Nariman’s core argument was simple: without accurate data, judicial reform would always be based on assumptions rather than evidence. He believed that regular, publicly available judicial statistics would help policymakers identify bottlenecks, understand patterns of delay, and design targeted reforms. Although it was never enacted, the idea behind the Bill remains significant and is a precursor to later initiatives like the National Judicial Data Grid.

The Judicial Statistics Bill, 2017

Once again, in 2017, Narayan Lal Panchariya once again proposed a judicial statistics bill which was much more elaborate than the 2004 bill which primarily focused on the need for official reliable judicial statistics and was restrained in terms of the data to be collected. Its emphasis was on transparency and aggregate performance indicators without intruding into court-room level details. The 2017 Bill adopted a much more prescriptive approach. It proposed collecting sensitive micro-level data including names of judges, lawyers appearing in cases, and hours spent. Additionally, it also proposed statutory authorities with dedicated budgets, audits, and reporting obligations. [9]

NJDG as Defined in official government report(s)

National Court Management System Report, 2012

Following the failure of legislative efforts, the issue continued to draw attention from institutional bodies. The National Court Management System (NCMS), in its 2012 report, highlighted that judicial statistics were often incomplete or incorrect and emphasised the need for a national network to collect uniform data.

245th Law Commission of India Report, 2014

It described the lack of complete judicial data as a major handicap in undertaking serious analysis and making informed policy recommendations.[10] As a result, judicial data collection in India functions without a dedicated legislative mandate, relying instead on administrative and technological initiatives such as the National Judicial Data Grid, which operates without a standalone statutory framework.

National Judicial Data Grid in case law(s)

Swapnil Tripathi v. Supreme Court of India [11]

In this case, the court reinforced open justice principles under Articles 14, 19, and 21, mandating live-streaming of key cases and linking such transparency to digital platforms, implicitly supporting NJDG's public data dissemination for reducing misinformation and building trust.

Data Recorded in the National Judicial Data Grid

The National Judicial Data Grid records day-to-day case data from courts across India using information entered in the e-Courts Case Information System. It shows how many cases are filed, pending, and disposed of in District, Taluka, and High Courts. As courts update case details, the numbers on NJDG change automatically, making it a live record of court workload. The data also includes information on how old cases are, whether orders have been uploaded, and how many cases are moving or stuck at different stages of proceedings

Parameters used to Classify Data

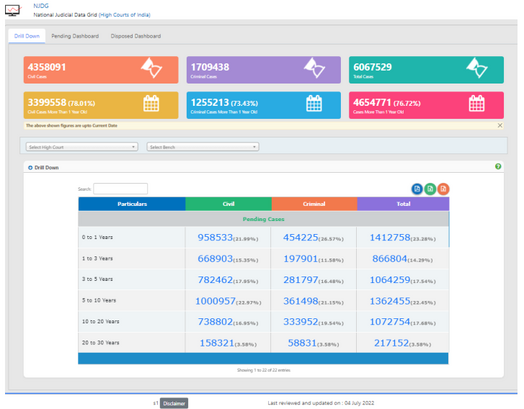

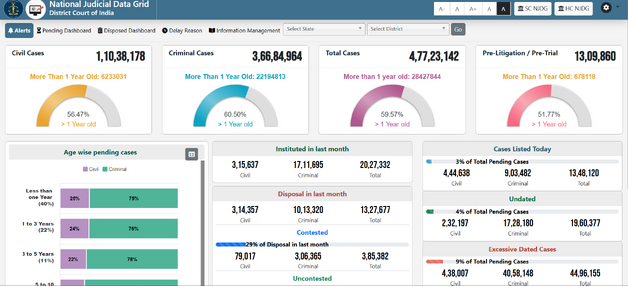

The National Judicial Data Grid (NJDG) classifies and presents judicial data across Indira through multiple parameters. At the most basic level, cases are categorized into Civil, Criminal, and Total Cases. In addition to these, there is also data on Pre-litigation and Pre-trial stages.

Each of these categories is further broken down based on the age of cases in percentage terms, particularly distinguishing between cases that are less than one year old and those that are older than one year.

A more detailed classification is available through the age-wise pendency data, which groups pending cases into the following time brackets: less than one year, one to three years, three to five years, five to ten years, and above ten years. For each of these categories, the NJDG displays the proportion of civil and criminal cases, enabling a comparative understanding of delays across different types of litigation.[12]

The platform also provides demographic-based and procedural statistics. These include data on cases involving women litigants, senior citizens, and the total number of pending cases. Additionally, NJDG tracks case movement by showing the number of cases instituted in the previous month and the number of cases disposed of in the previous month, further divided into contested and uncontested matters. Excessively delayed cases and undated cases are also separately highlighted.[13]

All of these statistics can be accessed at varying levels of granularity. Users can filter and view data for a specific State or District. The platform offers a separate “Pending Cases” dashboard and a “Disposed Cases” dashboard, each designed to present relevant metrics specifically structured.

In addition, the NJDG includes visual data representations, such as graphs showing reasons for delay at the court level for both civil and criminal cases. The website also provides state-wise summaries covering overall case statistics, along with judicial strength and judge-related data.[14] The NGDG website also provides 3 manuals regarding the functioning and the data presented by the different dashboards of the District Courts, High Courts, and Supreme Court.

International Experience

United Kingdom

Here, judicial data is made available through the Justice Data portal hosted by the Ministry of Justice. This portal publishes official statistical data on the operation of the courts and tribunals in England and Wales, drawing from administrative records compiled by HM Courts & Tribunals Service (HMCTS). The portal includes headline measures such as total disposals and open caseloads for Crown and magistrates’ courts, civil judgments, family court cases, and tribunal receipts and disposals, along with time-series data that illustrate trends in workloads and system performance. These figures are released on a quarterly basis and cover criminal, civil, family, and tribunal jurisdictions.[15]

United States of America

In the United States, the Public Access to Court Electronic Records (PACER) system functions as the federal judiciary’s central electronic access service for case and docket information. Managed by the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts, PACER allows users to retrieve case details and documents filed in federal district, appellate, and bankruptcy courts. Each court manages its own case records, and a portion of case metadata from these records is nightly transferred to a central index known as the PACER Case Locator. Additionally, the US also launched a Court Statistics Project (CSP), a long-running statistical initiative focused on collecting, analyzing, and publishing standardized data about state court systems. It serves as the most comprehensive national source for understanding how state courts operate, how many cases they handle, and how trends shift over time. Create Comparable Data: The CSP was established to develop a valid, uniform, and complete statistical database detailing the work of state courts such as trial courts and appellate courts so that data are consistent across all states.

Spain

In Spain, the Justice in Data (Justicia en Datos) portal serves as an open platform for official justice-related data. It aggregates and publishes judicial and administrative data related to the administration of justice, guided by a statutory framework that defines uniform criteria for data collection, processing, transmission, and use. The portal is supported by the National Judicial Statistics Commission, which standardizes the production of judicial statistics across jurisdictions, and by electronic judicial administration systems that ensure interoperability and quality. The Spanish portal presents thematic indicators and analytical tools, enabling users to explore justice activity across different dimensions.[16]

Open Courts in the Digital Age: A Prescription for an Open Data Policy by Vidhi

According to this report[17], The National Judicial Data Grid was created to address a long standing gap in India’s judicial system: the lack of reliable and detailed court statistics. For years, pendency and disposal figures were presented in broad civil and criminal categories, offering little insight into how different courts function or where delays actually occur. This absence of granular data has repeatedly been flagged by Parliament, the Law Commission, and judicial committees as a major obstacle to planning and reform.

With the rollout of the e Courts project, courts began capturing detailed case level information across the district judiciary. NJDG consolidated this data and made it publicly visible, marking a clear improvement over earlier systems. However, the platform largely publishes aggregated figures. It does not provide access to the underlying data needed to study case types, stages, judicial workload, or litigation trends. As a result, NJDG functions more as an overview tool than a foundation for serious empirical analysis.

The report argues that this is a policy choice rather than a technical limitation. Courts already collect far more data than what is released. What is missing is an open judicial data policy that governs how court data can be shared and reused. Such a policy would be rooted in the open courts principle, which treats access to judicial records as a core aspect of transparency, subject only to narrow and clearly defined exceptions.

Privacy concerns are recognized but seen as manageable. Existing law already permits protection in specific categories such as sexual offences, juvenile cases, matrimonial disputes, and matters involving national security. The report recommends addressing privacy upfront through anonymization in these limited cases, instead of restricting access to judicial data as a whole.

India Justice Report: Constructing an Evaluation Framework for Assessing Dashboards

Section 3.2 of this report[18] presents the National Judicial Data Grid as a significant institutional shift in how judicial information is made visible in India. It acknowledges that the NJDG has changed the landscape by bringing together case-level data from district and subordinate courts on a single public platform, allowing anyone to see broad patterns relating to filings, pendency, and disposals in near real time. This, the report notes, is a marked departure from the earlier situation where such information was scattered, irregular, or entirely unavailable, and it has helped move conversations on judicial delay away from anecdote and perception toward some degree of empirical grounding.

It also underlines the limits of what the NJDG currently offers. It points out that the quality of data entering the system varies significantly across states and courts, largely because of differences in data entry practices, infrastructure, and administrative capacity. The NJDG also remains focused on aggregate and status-based indicators, with little insight into how cases progress through different stages, why adjournments are granted, or where delays are concentrated within the life cycle of a case. As a result, while the NJDG improves transparency and enables basic monitoring, the report suggests that it falls short as a tool for diagnosing structural problems in the justice system or for designing targeted access-to-justice reforms.

Challenges Faced in the National Judicial Data Grid (NJDG)

Despite substantial public investment exceeding 2,308 crore in the eCourts project since 2005, the NJDG continues to face critical reliability and transparency issues:

- Inherent Data Inaccuracies: The platform carries a prominent disclaimer stating that its data is general in nature, not a substitute for authentic records, and must be cross-verified with individual courts, reflecting deep-seated systemic flaws.

- Inflated Disposal Statistics: Reported disposal rates frequently appear unrealistic and exaggerated when compared to established judicial performance benchmarks.

- Double Counting of Cases: Instances of the same case being recorded multiple times distort pendency and disposal figures.

- Inconsistent Case Logging Practices: Criminal proceedings register interlocutory applications (e.g. repeated bail petitions) as separate cases, while civil matters consolidate them under a single case number, leading to artificial inflation of overall caseload metrics.

- Broader Judicial Opacity: Lack of transparency in administrative functions including record management, finances, and infrastructure, extends to statistical reporting, impeding meaningful accountability and analysis of litigation patterns.

- Resistance to External Scrutiny: The judiciary has historically declined to share performance data with Parliament and other oversight bodies, sometimes invoking constitutional provisions in ways that limit public and legislative oversight.

These interconnected challenges significantly undermine the NJDG's credibility as a tool for monitoring judicial performance and informing reform efforts.

Way Forward

Parliament should impose a clear statutory obligation on the judiciary to publish reliable and meaningful judicial statistics, including data on the functioning of the district judiciary under the administrative control of the High Courts. The law must clearly define the data points to be disclosed and should incorporate the core parameters originally envisaged in Fali Nariman’s Judicial Statistics Bill. To ensure accountability, the Chief Justice of each High Court should be required to certify the accuracy of this data and place an annual consolidated judicial statistics report before the Speaker of the State Legislative Assembly. Since initiatives such as the e-Committee of the Supreme Court and the National Judicial Data Grid are entirely funded by Parliament, the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Law and Justice should undertake a review of their functioning and data quality. Such oversight would not intrude into adjudicatory independence, but would strengthen transparency and democratic accountability in the administration of justice.[19]

References

- ↑ https://ecommitteesci.gov.in/publication/district-courts-of-india-national-judicial-data-grid-njdg-dc/

- ↑ https://ecommitteesci.gov.in/publication/district-courts-of-india-national-judicial-data-grid-njdg-dc/

- ↑ https://ecommitteesci.gov.in/publication/high-courts-of-india-national-judicial-data-grid-njdg-hc-2/

- ↑ https://ecommitteesci.gov.in/publication/supreme-court-of-india-national-judicial-data-grid-njdg-sc-2/

- ↑ https://doj.gov.in/the-national-judicial-data-grid-njdg/

- ↑ https://www.nic.gov.in/project/national-judicial-data-grid/

- ↑ https://ecommitteesci.gov.in/service/national-judicial-data-grid/

- ↑ https://rsdebate.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/50335/2/ID_203_03122004_3_p189_p189_35.pdf

- ↑ https://sansad.in/rs/legislation/bills

- ↑ https://cdnbbsr.s3waas.gov.in/s3ca0daec69b5adc880fb464895726dbdf/uploads/2022/08/2022081643.pdf

- ↑ (2018) 10 SCC 639; AIR 2018 SC 4806; Writ Petition (Civil) No. 1232 of 2017

- ↑ https://cdnbbsr.s3waas.gov.in/s388ef51f0bf911e452e8dbb1d807a81ab/uploads/2018/07/2022120782.pdf

- ↑ https://ecommitteesci.gov.in/service/national-judicial-data-grid/

- ↑ https://njdg.ecourts.gov.in/njdg_v3//?p=home&app_token=63e61755a2c03646f86775f536ec071b0fa841a2efab3db89f370aca214e8d66

- ↑ https://data.justice.gov.uk/

- ↑ https://datos.justicia.es/en/

- ↑ https://images.assettype.com/barandbench/import/2019/11/Open-Data-Final-Report.pdf

- ↑ https://indiajusticereport.org/files/Evaluation-Framework-A2J-Lab_India-March22,%202024.pdf

- ↑ Abhinav Chandrachud, Tareekh Pe Justice: Reforms for India’s Courts (Penguin Random House India, 2022).