Plea Bargain

What is a Plea Bargain?

Plea bargaining is an active negotiation process wherein an offender voluntarily agrees to plead guilty before a court, often in exchange for a reduced sentence or lesser charge. This process usually takes place prior to trial, though it may occur at any stage before judgment is rendered. Historically, the practice of plea bargaining in the United States can be traced back to the 19th century, notably in Alameda County, California. While it was not as prevalent then as it is today, the judiciary did recognize and credit guilty pleas, reflecting the early emergence of this procedural mechanism.[1]

According to Black’s Law Dictionary, plea bargaining means: “The process whereby, the accused and the prosecutor, in a criminal case, work out a mutually disposition satisfactory of the case subject to court approval. It usually involves the defendant’s pleading guilty to a lesser offence or to only one or some of the counts of a multi-count indictment in return for a lighter sentence than that possible for the graver charge.”

Marriam-Webster defines plea Bargain as “The negotiation of an agreement between a prosecutor and a defendant whereby the defendant is permitted to plead guilty to a reduced charge,”[2] while the Cambridge Dictionary describes it as “An agreement to allow someone accused of a crime to admit to being guilty of a less serious crime, in order to avoid being tried for the more serious one.”[3]

Thus, Plea bargaining may be defined as an agreement in a criminal case between the prosecution and the defense by which the accused changes his plea from not guilty to guilty in return for an offer by the prosecution or when the judge has informally made the accused aware that his sentence will be minimized, if the accused pleads guilty. In other words, it is an instrument of criminal procedure which reduces enforcement costs (for both parties) and allows the prosecutor to concentrate on more meritorious cases.[4]

Official Definition of a Plea Bargain

Plea Bargain as defined in Legislations

Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023

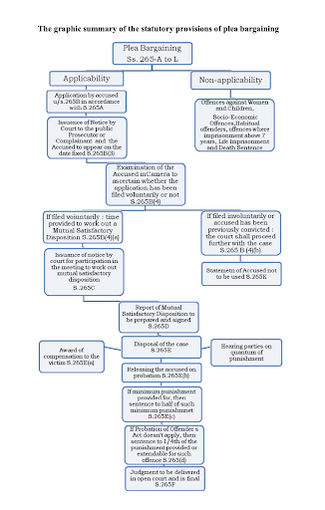

Chapter XXIII of the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023 (corresponding to Chapter XXI-A of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973) introduced the concept of plea bargaining in India through Sections 265A to 265L. These provisions establish the statutory framework for plea bargaining and specify the procedure to be followed. Under Section 265B, the accused may initiate a plea bargaining application after the court has taken cognisance of the offence but before the commencement of trial. Once the court is satisfied that such an application has been made voluntarily, it proceeds to facilitate a mutually satisfactory disposition of the case in accordance with Sections 265C and 265D.

Scope of Plea Bargaining under BNSS

Section 265A lays down the scope of plea bargaining, providing that an accused may apply for plea bargaining in respect of offences for which the prescribed punishment is imprisonment of up to seven years, provided that such offences do not affect the socio-economic condition of the country and are not committed against a woman or a child below fourteen years of age.

- (a) Where the police have filed a report under Section 173 of the Code, alleging commission of an offence punishable with imprisonment up to seven years; or

- (b) Where a Magistrate has taken cognisance of an offence on complaint and the offence is punishable with imprisonment up to seven years.However, offenses that have impacted socio-economic conditions of the country or have been committed against a woman or a child of below 14 years of age have been kept out of the purview of the application of this chapter.

However, the Central Government, in exercise of powers under Section 265A(2) CrPC, has notified certain offences that are excluded from the scope of plea bargaining, particularly those having an impact on the socio-economic condition of the country or those committed against women or children below the age of fourteen years.[5] These are:

- Dowry Prohibition Act, 1961

- The Commission of Sati Prevention Act, 1987

- The Indecent Representation of Women (Prohibition) Act, 1986

- The Immoral Traffic (Prevention) Act, 1956

- Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005

- The Infant Milk Substitutes, Feeding Bottles and Infant Foods (Regulation of Production, Supply and Distribution) Act, 1992

- Provisions of Fruit Products Order, 1955 (issued under the Essential Services Commodities Act, 1955)

- Provisions of Meat Food Products Orders, 1973 (issued under the Essential Commodities Act, 1955)

- Offences with respect to animals that find place in Schedule I and Part II of the Schedule II as well as offences related to altering of boundaries of protected areas under Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972

- The Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989

- Offences mentioned in the Protection of Civil Rights Act, 1955

- Offences listed in Sections 23 to 28 of the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2000

- The Army Act, 1950

- The Air Force Act, 1950

- The Navy Act, 1957

- Offences specified in Sections 59 to 81 and 83 of the Delhi Metro Railway (Operation and Maintenance) Act, 2002

- The Explosives Act, 1884

- Offences specified in Sections 11 to 18 of the Cable Television Networks (Regulation) Act, 1995

- Cinematograph Act, 1952

Procedural Aspects under the BNSS

Section 265B of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 prescribes the procedure for filing an application for plea bargaining. The accused must submit an application in writing to the court, which, upon being satisfied that the application has been made voluntarily, shall issue notice to the prosecutor or the complainant, as the case may be, to facilitate a mutually satisfactory disposition of the case.[6]

The guidelines for arriving at such mutually satisfactory disposition are laid down under Section 265C, which mandates the participation of the prosecutor, the accused, the victim, and, where appropriate, the investigating officer, in the process.[7] Once a settlement has been reached, Section 265D requires the court to prepare a report of the disposition signed by the presiding officer and the parties involved, and to proceed with the disposal of the case in accordance with the agreed terms.[8]

Further, Sections 265E to 265G collectively govern the court’s discretion and the conditions for refusal or withdrawal of a plea bargaining application. The court may refuse an application if it is not voluntary, not in the interest of justice, involves a minor victim, or where public interest requires continuation of the trial. The court may also seek modifications in the proposed terms, and the accused is permitted to withdraw the application before judgment, in which case the case proceeds normally, and Section 265H provides that once the court accepts the mutually agreed terms, it shall dispose of the case in accordance with the agreement, and the trial is deemed concluded with the consent of the parties. Additionally, under Section 265I, any period of detention already undergone by the accused during investigation, inquiry, or trial shall be set off against the term of imprisonment imposed in the final judgment.[9]

Modifications under BNSS

The Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023 (BNSS) substantially modifies and refines the plea-bargaining framework that was first introduced in India through Chapter XXIA of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (CrPC) by the Criminal Law (Amendment) Act, 2005. One of the most notable changes is the prescription of definite timelines for initiating and concluding the plea-bargaining process. Section 289 of the BNSS now mandates that an accused person must file an application for plea bargaining within thirty days from the date on which the charge is framed by the court—whereas the CrPC provisions under Section 265B contained no such deadline.[10] After such an application is filed, the court may allow the parties a period not exceeding sixty days to arrive at a mutually satisfactory disposition (MSD) between the accused, the prosecutor, and the victim or complainant.[11] This introduction of statutory timelines aims to prevent procedural delays and strengthen the element of certainty in criminal negotiations.

The BNSS also introduces enhanced leniency for first-time offenders. Under the new framework, where an offence prescribes a minimum term of imprisonment, the court may impose only one-fourth of the minimum sentence in cases resolved through plea bargaining. If no minimum is prescribed, the punishment may be reduced to one-sixth of the prescribed maximum term for first-time offenders.[11] These provisions reflect a rehabilitative and reformative approach, acknowledging the distinction between habitual offenders and those without prior convictions. Further, Section 299 of the BNSS expressly provides that statements or facts disclosed by an accused in the course of plea bargaining shall not be used for any other purpose, thereby introducing a clear statutory safeguard to protect the voluntariness and fairness of the process.[12]

In addition, BNSS retains the limited scope of plea bargaining as recognised under the CrPC—applicable only to offences punishable with imprisonment up to seven years, and not to offences affecting the socio-economic condition of the country or those committed against women or children.[13] It remains a form of “sentence bargaining”, meaning that while the accused may negotiate the extent of punishment, there can be no bargaining over guilt or alteration of the charge itself. The Sanhita also makes the role of the court more structured: judges are required to ensure that the application is filed voluntarily, that the accused comprehends the implications of the plea, and that the settlement reached complies with the statutory requirements.[^6] Collectively, these modifications demonstrate the legislature’s intent to strengthen procedural fairness, transparency, and voluntariness in plea bargaining while maintaining judicial oversight within defined time frames.[14]

Procedural Differences between Plea Bargaining under the CrPC and the BNSS

Under both the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (CrPC) and the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023 (BNSS), plea bargaining serves as a mechanism allowing an accused to plead guilty in exchange for a lesser sentence or reduced charge, but the BNSS introduces a few procedural refinements. While the CrPC contained these provisions in Chapter XXIA (Sections 265A–265L), they are now placed under Chapter XXI (Sections 289–303) in the BNSS, with the overall framework retained. The eligibility criteria remain largely the same—plea bargaining is permissible for offences punishable with imprisonment up to seven years and not for offences against women or children—but the BNSS explicitly reaffirms the exclusion of offences affecting the “socio-economic condition of the country” as notified by the government. Procedurally, both laws require the accused to file a written application before the trial court, which then notifies the prosecution and the complainant and conducts an inquiry to ensure that the application is made voluntarily. However, the BNSS strengthens safeguards for voluntariness and informed consent by mandating that the court personally satisfy itself that the accused understands the nature and consequences of the plea. The negotiation stage, involving a “mutually satisfactory disposition,” is retained, but the BNSS places greater emphasis on the participation of the victim and the inclusion of compensation as part of the negotiated outcome. In essence, the BNSS preserves the CrPC’s structure but makes the process more rights-oriented, transparent, and sensitive to the victim’s role within plea bargaining.

Plea Bargain as Defined in Official Government Reports

Law Commission Report

142nd Law Commission Report

142nd Law Commission Report, which recommended incorporation of plea bargaining in the Indian Legal Justice System defined “Plea Bargaining” as “ …pre-trial negotiations, usually conducted by the counsel and the prosecution, during which the defendant agrees to plead guilty in exchange for certain concessions by the Prosecutor …”[1]

It further explicated on the distinction between “charge-bargaining” and “sentence bargaining”. The former refers to a promise by the prosecutor to dismiss or reduce some of the charges brought against the defendant in exchange for a guilty plea. The latter refers to a promise by the prosecutor to recommend a specific sentence or to refrain from making any sentence recommendation in exchange for a guilty plea.

154th Law Commission Report

Plea Bargaining was introduced in India by an amendment of the Code of Criminal Procedure in 2005 by the Criminal Law (Amendment) Act, 2005. It allows plea bargaining for offenses with punishment upto seven years imprisonment. But, it excludes offenses affecting the socio-economic condition of the country or offenses committed against a woman or a child below the age of fourteen are excluded.[15]

The Law Commission of India beneath the Chairmanship of Justice K. Jayachandra Reddy gave his 154th Report on Cr.P.C. 1973 (Act No. 2 of 1974) in the year 1996, in this Report, the Law Commission examined the Cr.P.C. with a view to doing a comprehensive revision of the code. The plea bargaining concept is discussed in separate Chapter XIII. The Commission discussed the issue of pendency and problem of undertrial prisoners and has given the following recommendation in para 9 of the Report.: On Reform of Criminal Justice System, in 2000 The Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India constituted a Committee. This Committee beneath the Chairmanship of Justice V.S. Malimath presented its Report in the year 2003.

Malimath Committee Report

This committee is known as the Criminal Justice Reform Committee or Malimath Committee (hereinafter Malimath Committee). In this Report, in Part I. Fundamental Principles, Chapter 6 is on victim to Justice. In this Chapter, Committee stated that: “The Committee is in favour of giving the role to the victim in the negotiation leading to settlement of criminal cases either through Courts, Lok Adalats or Plea bargaining.”the Malimath Committee briefly discussed on plea bargaining and provisions of compounding of offences and suggested for implementation of plea bargaining. The Committee, chaired by V. S. Malimath, was constituted in 2000 by the Indian Government to examine the functioning of the criminal justice system (investigation, trial, sentencing) and suggest wide-ranging reforms.  In its 2003 report it recommended the introduction of plea bargaining as one of the mechanisms to reduce delay, alleviate the burden of cases on courts and prisons, and enable more efficient disposal of criminal matters.  The Committee suggested that plea bargaining could be applied to offences that are not of a “serious nature” (i.e., those where the value to society is limited, victim-impact rather than widespread societal harm) and that such a mechanism would allow the victim-party greater involvement, streamline proceedings and deliver quicker justice.  Among its broader recommendations, the Committee also sought to strengthen victim rights, make courts more responsive, reduce backlog, and modernise investigation and trial procedures.  However, human rights critiques (e.g., by Amnesty International) observed that the report paid insufficient attention to issues affecting marginalised groups, access to legal aid, and safeguarding trial rights in the context of reforms including plea bargaining.

Parliamentary Committee Report

111th report on Criminal Law (Amendment) Bill, 2003 (Rajya Sabha)

The Parliamentary Standing Committee was constituted on 5th August 2004, on Home Affairs by Rajya Sabha, under the Chairmanship of Smt. Sushama Swaraj. The Committee held a discussion on Criminal Law (Amendment) Bill, 2003 and presented its 111th Report to Rajya Sabha on 2nd March 2005 and Lok Sabha on 4th March 2005. In this Report Committee recommended recommendations regarding plea bargaining as follows: “The Committee even keeping in mind the views of the witnesses on plea bargaining consider that as a pragmatic approach to management of crime and streamlining of the criminal justice administration under a system burdened with three crore pending cases, some dispensations which are fair, just and reasonable can be considered. However, it is of the strong view that this provision of plea bargaining should be introduced only after putting in place the Directorate of Prosecution as envisaged in the Code of Criminal Procedure (Amendment) Bill, 1994 and endorsed by the Committee. It feels that there is no rational for introducing plea bargaining in the absence of the institution of the independent Directorate of Prosecution and empowering courts to settle the cases through ‘plea bargaining.’ Thus the Parliamentary Committee also insisted and suggested for insertion of provisions of plea bargaining in Cr.P.C.

As defined in Case laws

The judiciary in India has shown high reluctance with respect to resorting to the procedure of plea bargaining, and has also on several occasions rejected the same even after the various contentions made through the Law Commissions Reports.

The earliest cases in which the concept of plea bargaining was considered by the Hon'ble Court was Madanlal Ramchander Daga v. State of Maharashtra[16] in which the court observed - "In our opinion, it is very wrong for a court to enter into a bargain of this character Offences should be tried and punished according to the guilt of the accused. If the Court thinks that leniency can be shown on the facts of the case it may impose a lighter sentence."

Further, In Muralidhar Megh Raj v. State of Maharashtra the Apex Court continued to disapprove the concept of plea bargaining when the appellants pleaded guilty to the charge where-upon the trial Magistrate, sentenced them each to a piffling fine. The Court observed: "To begin with, we are free to confess to a hunch that the appellants had hastened with their pleas of guilty hopefully, induced by an informal, tripartite understanding of light sentence in lieu of nolo contendere stance."

However, after the amendment, the concept of plea bargaining has found recognition in the Indian Courts since the court is left with no option but to interpret the law and not make laws. The courts have held that criminals who admit their guilt and repent upon, a lenient view should be taken, while awarding punishment.[17]

Following the introduction of Chapter XXIA in the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 by the Criminal Law (Amendment) Act, 2005, the Indian judiciary has increasingly recognised and clarified the scope of plea bargaining. The Supreme Court in Vipul v State of Uttar Pradesh emphasised that plea bargaining under Chapter XXIA serves a “laudable objective” of facilitating expeditious justice while ensuring the participation of all stakeholders, including the victim. The Court further clarified that the consensual aspect of plea bargaining relates primarily to the quantum of sentence once guilt is admitted and underscored the duty of courts to inform the accused about the availability of this statutory mechanism at the appropriate stage of proceedings.[18] Similarly, in G Venkateshan v State, the Madras High Court (2024) held that not all offences committed against women are automatically excluded from the ambit of plea bargaining; only gender-centric offences such as those under Sections 354 or 376 IPC fall outside its scope. The Court directed that, after the framing of charges, trial courts must inform the accused in writing of their eligibility to apply for plea bargaining under Chapter XXIA of the CrPC or its corresponding provisions under the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023.[19]

Thus, across these post-amendment judgments, the consistent judicial understanding is that plea bargaining, when undertaken voluntarily and in accordance with procedural safeguards, is a legitimate means to secure “mutually satisfactory disposition” without undermining the fairness of the criminal process.

The court in Re: Policy Strategy for grant of bail provided some suggestions for effectuating the provisions related to plea bargaining.[20] The suggestions provided by the division bench regarding plea bargaining entail a structured approach to facilitate the disposal of criminal cases. The court proposed the selection of specific courts as pilot cases to identify suitable cases for plea bargaining. These courts are instructed to identify cases pending at pre-trial or evidence stages, involving offences with a maximum sentence of 7 years' imprisonment, excluding certain specified offences. Notices are to be issued to the parties involved, informing them of the court's intention to consider disposing of the cases through plea bargaining. Public Prosecutors are tasked with assessing the criminal antecedents of the accused, with only cases involving first-time offenders being considered. The court is directed to explain the provisions of plea bargaining to the accused, allowing them time to consider their options. In cases where the under trial is in judicial custody, the court is to facilitate the provision of legal aid and explain the available options to the accused. Additionally, a timeline of 4 months is stipulated for the entire process, encompassing training of judicial officers, identification of cases, notice to the parties, and consideration of the matter. These measures aim to expedite the disposal of criminal cases and provide opportunities for resolution through alternative mechanisms while upholding the principles of justice and fairness.

Types of Plea Bargaining

Plea Bargaining can be divided into three types- (1) Charge Bargaining; (2) Sentence Bargaining; and (3) Fact Bargaining. Each type involves implied sentence reductions but differs in the ways of achieving those reductions.[21]

Charge Bargaining

It involves bargaining over the nature or number of charges against the accused. Under this type, more serious charges may be dropped or reduced, or multiple charges trimmed down in exchange for a plea of guilty to one or more less serious charges. For example, an accused charged with offences A, B and C might plead to only B or a lesser version of A, while A and/or C are dropped. This type helps reduce exposure to more serious liability.[22]

Sometimes “multiple charge bargaining” or “unique charge bargaining” are terms used under the broader “charge bargaining” rubric. Multiple charge bargaining means dropping some of the various charges; unique charge bargaining might mean substituting a more serious charge for a less serious one. These distinctions help clarify the kind of concessions made by prosecution.[23]

Sentence Bargaining

This refers to the situation where the accused admits guilt (or pleads guilty) to a specified charge, but negotiates for a lighter or reduced sentence compared to what might have been imposed in a full trial. The negotiation is over the quantum of punishment rather than whether guilt is admitted. This is the type most directly reflected in Indian statute under CrPC (and under the newer BNSS) where, if plea bargaining is accepted, there are specific provisions about how much the sentence may be reduced in certain cases (e.g. for first time offenders). Commentary often treats this as the default type when people speak of plea bargaining in India.[24]

Fact Bargaining

This involves the accused agreeing to admit certain facts or stipulate to a factual version which may exclude aggravating circumstances, or the prosecution agreeing not to contest certain facts. Thus, some facts that could make the offence more grave (or lead to greater sentencing) might be withheld or not pursued in evidence. Some commentators argue this form is less compatible with principles of justice, since it may allow distortion or concealment of true facts.[25]

Difference between plea bargain and a guilty plea - The guilty plea means to confess or admit. The person who is charged with an offence admits his offence or responsibility. Simplest meaning of a guilty plea is “admission of offence by the accused”. After framing of charge at that time if the accused admits his guilt, then the judge shall record the plea of accused, convict him in his discretion, convict him thereon and trial ends at that moment.

Plea Bargaining vs. Compounding

Although both plea bargaining and compounding of offences aim to achieve the expeditious disposal of criminal cases through negotiated resolution, they differ fundamentally in their nature, scope, and legal consequences. Plea bargaining, introduced by the Code of Criminal Procedure (Amendment) Act 2005 and codified under Chapter XXI-A (sections 265A–265L), is a statutory mechanism allowing the accused to voluntarily plead guilty in exchange for a lesser sentence, subject to the court’s scrutiny.[26] In contrast, compounding of offences under section 320 of the Code of Criminal Procedure 1973 permits certain offences to be settled privately between the victim and the accused, resulting in an acquittal of the latter.[27] While plea bargaining involves negotiation between the prosecution and the accused under judicial supervision, compounding rests on the consent of the victim, and its scope is confined to offences specifically enumerated by statute.[28] Thus, plea bargaining represents a judicially monitored reformative measure, whereas compounding remains a consensual settlement rooted in restorative justice principles.[29]

Appearance in Official Database

Crime In India Report

Crime in India Report prepared by National Crime Records Bureau, contains statistics regarding disposal of cases through different methods, one of which is plea bargaining.

This table showcases court disposal of economic offenses in India.

This table shows court disposal of crimes against senior citizens in the year 2021, total number of plea bargains in this case were 158.

This table depicts state/ut wise crimes. While the aim of introducing Plea Bargaining in India was to relieve the courts of an insurmountable burden, the practical application of the same has largely remained on a very small level. The problem seems to be present more on an implementational level rather than legislative. Plea bargaining is also known as ‘plea deals’ or ‘plea agreements’ or ‘plea in mitigation’ or ‘copping a plea”.

Plea Bargaining In Other Countries

U.S.A

“Plea bargaining is a defining, if not the defining, feature of the federal criminal justice system” According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics (2005), in 2003 there were 75,573 cases disposed of in federal district court by trial or plea. Of these, about 95 percent were disposed of by a guilty plea (Pastore and Maguire, 2003). While there are no exact estimates of the proportion of cases that are resolved through plea bargaining, scholars estimate that about 90 to 95 percent of both federal and state court cases are resolved through this process.[30]

Plea bargaining in US is permissible in all types of cases, including terrorism and murder cases too, but in a particular case, the prosecution may reject or to be instructed to reject negotiation. In the United States, only after negotiations among the accused as well as the prosecutor is over, application for plea bargaining is filed. Ascertaining the voluntariness of application is not binding on the judge.

In the United States, the accused has three options with respect to pleas; guilty, not guilty or plea of nolo contendere[31]. In plea of nolo contendere the defendant answers the charges made in the indictment by declining to dispute or admit the fact of his or her guilt. The defendant who pleads nolo contendere submits for a judgment fixing a fine or sentences the same as if he or she had pleaded guilty. The difference is that a plea of nolo contendere cannot later be used to prove wrongdoing in a civil suit for monetary damages, but a plea of guilty can.[32]

The Indian concept of plea bargaining is inspired from the Doctrine of Nolo Contendere. It has been incorporated by the legislature after several law commission recommendations. This doctrine has been considered and implemented in a manner that takes into account the social and economic conditions prevailing in our country.

However, Plea Bargaining forms a major part of the Federal Justice system in US in contrast to India where it has an otiose existence only to unburden the courts on paper.

Canada

The Supreme Court of Canada has recognized plea bargaining as an essential part of the exercise of Crown discretion; R. v. Anderson, 2014 SCC 41. Making an informed decision about which charges are to be proceeded upon and whether to accept a plea to a lesser charge are two examples set out in Anderson as being essential roles for a Crown Attorney.[33]

In Canada, it appears that about 90% of criminal cases are resolved through the acceptance of guilty pleas: many of these pleas are the direct outcome of successful plea negotiations between Crown and defense counsel.[34]

In Canada also, no restriction has been placed on the application of Plea Bargaining and can occur in all cases. Where a plea bargain has been implemented, the Crown and the accused effectively determine the nature of the charge(s) that will be laid. Since the nature and quantum of sentences are primarily based on the charge(s) brought against the accused, it is clear that the parties to a successful plea negotiation enjoy the de facto power to exercise a considerable degree of influence over the sentence that is ultimately imposed by the trial judge.

England

Plea Bargaining is not officially part of the system in England and Wales, except in complex fraud cases, but the judicial sentencing guidelines suggest those who plead guilty at the earliest hearing over other crimes may be given a reduction of up to a third of their sentence. There is a sliding scale of sentence reductions as criminal proceedings continue, and informal bargaining is widespread.[35] Under Section 144 of the Criminal Justice Act 2003, courts must consider the stage and circumstances of a guilty plea while sentencing.[36] The Sentencing Council’s Guideline on Reduction in Sentence for a Guilty Plea (2017) allows up to a one-third reduction for pleas entered at the first opportunity, reducing gradually for later pleas.[37] Though not a negotiated deal as in the U.S., such provisions encourage efficiency and conserve judicial time. Informal plea discussions, known as a “basis of plea”, often occur between prosecution and defence to agree on undisputed facts, subject to the court’s approval.[38] Studies show that most criminal cases in England and Wales conclude through guilty pleas, reflecting a functional but regulated form of plea bargaining.[39]

Problems with Plea Bargaining

Plea Bargain is a closed process which means that the data related to it will not be readily available and therefore much of the research is based on personal interviews, observations and questionnaires. However, Plea bargaining, while promising faster disposal of criminal cases, faces serious challenges. According to the SVP National Police Academy, these challenges include “procedural inconsistencies, potential for coercion, and uneven application,” which collectively impede the realization of its intended benefits.[40]

The National Judicial Academy highlights that the low usage of plea bargaining is attributed to factors such as “limited awareness among the people, untrained judicial officers and lawyers with respect to implementation of plea bargaining, ambiguous nature of law, and restricted applicability of Chapter XXI-A.”[41]

These issues underscore the need for comprehensive reforms to address the procedural inconsistencies and to enhance the understanding and application of plea bargaining within the Indian criminal justice system.

Reasons for Its Failure

According to official data, a meagre 0.045% (4,816) of the criminal cases were settled under the Plea-Bargain law in 2015 which further declined to 0.043% (4,887) in 2016. Moreover, number of under-trial prisoners also show an upwards trajectory. Thus, the Plea-Bargain law failed to achieve either of the two objectives that it was intended to fulfil.[42]

Reasons such as crude replication of an American model without making necessary modifications for an Indian socio-economic and cultural conditions (Biswas), extreme regulation on its application as compared to in US (Sekhri), have attributed to failure of Plea Bargain in India. Further more attractive options are available such as compounding of offences which avoids the stigma of “conviction” present in plea bargaining, or High Court can be.[42]

Research that engages with

The practice of plea bargaining under the clever camouflage of ‘plead guilty’ was employed as an outrageous affront to the sense and cause of justice. The year 1973 in the state of Gujarat witnessed a popular practice of letting off accused in food adulteration cases at ridiculously low sentences/fine upon pleading guilty. Such plea-bargaining practices became a recurring feature in certain types of criminal cases without a sense of judicial restraint and accountability. This ‘chronic disease’ of plea bargaining was sought to be arrested, remedied and uprooted.

The idea of introducing plea bargaining in the Indian jurisdiction was emphasized in the case of Barey and Ors. v. State188 owing to the gigantic problem of pendency in High Court. Thereafter, the option of plea bargain was proposed to be offered in all the pending criminal appeals before a single judge bench. The Court has the discretion to not send them to jail or modify their sentence to sentence of fine or the period already undergone. However, this provision was made only for cases up to the year of 1991.

Prior to the year 2000, the Apex court was essentially against the idea of disposal of criminal cases via plea-bargaining. It was majorly agreed that mere acceptance or admission of guilt should not be a ground for reduction of sentence and the case must be decided on merits and sentence should be commensurate with the offence.189 Plea bargaining was not recognized and is against public policy under our criminal justice system. This mechanism has time and again been disapproved by the courts for varied reasons such as giving way to corruption, collusion, polluting the pure fountain of justice and violative of the spirit of the Constitution.

However, owing to the criminal system groaning under the weight of cases filed, alternative solutions are sought after the world over. The use of already existing provision of compounding was encouraged. In relation to offences not compoundable, a conscious decision was taken to introduce the mechanism of plea bargaining where substantive sentence of imprisonment in jail deserved to be imposed on an offender who pleads guilty while invoking the scheme of concessional statement. This was a departure from the scheme of plea-bargaining prevailing in other countries where the offender is let off at a ridiculously low sentence.

THE PLEA BARGAINING CONTROVERSY* DOUGLAS A SMITH**

In The Plea Bargaining Controversy (1987), D.A. Smith critically examines plea bargaining as the dominant mechanism of criminal case disposal, defining it as the process where a defendant pleads guilty in exchange for reduced charges or sentences. Smith traces its evolution in the U.S. from a once-disfavored practice to an institutionalized norm, arguing that while it enhances efficiency by reducing court burdens and ensuring speedy resolutions, it simultaneously undermines fairness and the integrity of trial rights. The article highlights concerns of coercion—particularly the “trial penalty” that pressures defendants into guilty pleas—along with disparities arising from prosecutorial discretion and unequal bargaining power. Smith warns that the normalization of plea bargaining risks transforming justice into a transactional process driven by expediency rather than truth, shifting power from judges to prosecutors and potentially inducing innocent defendants to plead guilty. He concludes that although plea bargaining may appear pragmatic, it raises deep ethical and procedural questions that demand empirical and policy-level scrutiny.

The Bargain Has Been Struck: A Case for Plea Bargaining in India (NLSIR)

Kathuria’s article examines the insertion of Chapter XXIA into the Criminal Law (Amendment) Act, 2005, which formally introduced plea-bargaining into the Indian criminal justice system, and argues that this mechanism should be embraced rather than rejected. The author traces how plea-bargaining offers a potential solution for the heavy case-load and systemic delays afflicting Indian courts, emphasising its efficiency gains: by enabling prosecutors and defendants to negotiate resolutions short of full trial, the system may conserve resources, accelerate finality and reduce backlog. At the same time, Kathuria acknowledges the vulnerabilities of such a system in the Indian context—such as the risk of procedural unfairness, the power imbalance between accused and prosecution, and the possibility that innocent defendants may feel coerced into pleas—but contends that with proper safeguards—judicial oversight, transparency of legal counsel, and fixed criteria for admissibility—it can align with principles of justice. Importantly, the article situates India’s adoption of plea-bargaining not merely as a transplant of Western models, but as a culturally and procedurally adapted reform: it emphasises that the Indian law provides for only certain types of crimes (non-serious offences) to be eligible, limiting potential abuse. Kathuria concludes that when implemented with caution and procedural rigour, plea-bargaining represents a pragmatic reform toward a fairer and more efficient criminal justice system in India—balancing the tension between speed and rights.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 142 Law Commission Report, Government of India, <https://patnahighcourt.gov.in/bja/PDF/UPLOADED/BJA/MISC/392.PDF>

- ↑ Merriam-Webster, plea bargaining, available at https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/plea%20bargaining.

- ↑ Cambridge Dictionary, “plea bargain”, available at https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/plea-bargain

- ↑ “Disposal of Case Without Trial”, Krishna District, <https://districts.ecourts.gov.in/sites/default/files/Second%20topic.pdf>

- ↑ Ministry of Home Affairs Notification, S.O. 1042(E), The Gazette of India: Extraordinary, Part II, Section 3(ii) (11 July 2006) — notified offences under s 265A(2) CrPC.

- ↑ Code of Criminal Procedure 1973, s 265B (inserted by the Criminal Law (Amendment) Act 2005).

- ↑ ibid s 265C.

- ↑ ibid s 265D.

- ↑ ibid s 265l.

- ↑ ‘Section 290 BNSS (Equivalent to CrPC Section 265B)’ Prashant Kanha Blog (2024) https://www.prashantkanha.com/section-290-bnss-bhartiya-nagarik-suraksha-sanhita-2023-equivalent-cr-p-c-section/ accessed 15 October 2025.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 ‘Navigating through Criminal Law Reforms – Part II: Review of the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023’ Nishith Desai Associates (2024) https://nishithdesai.com/hotline.aspx/hotline.aspx/navigating-through-criminal-law-reforms-part-ii-review-of-bharatiya-nagarik-suraksha-sanhita-2023-replacing-the-code-of-criminal-procedure-1973-14897 accessed 15 October 2025.

- ↑ ‘Section 299 BNSS – Statements of Accused Not to Be Used’ ApniLaw (2024) https://www.apnilaw.com/bare-act/bnss/section-299-bharatiya-nagarik-suraksha-sanhitabnss-statements-of-accused-not-to-be-used/ accessed 15 October 2025.

- ↑ ‘The Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023’ PRS Legislative Research (2023) https://prsindia.org/billtrack/the-bharatiya-nagarik-suraksha-second-sanhita-2023 accessed 15 October 2025.

- ↑ ‘Plea Bargaining under BNSS (Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023)’ Legal Service India (2024) https://www.legalserviceindia.com/legal/article-17318-plea-bargaining-under-bnss-bharatiya-nagarik-suraksha-sanhita-2023-.html accessed 15 October 2025.

- ↑ “Plea Bargaining”, < https://legalservices.maharashtra.gov.in/Site/Upload/Pdf/plea-bargaining.pdf>

- ↑ AIR 1968 SC 1267

- ↑ State of Gujarat v. Natwar Harchanji Thankor 2005 Crl.L.J 2957 (Guj)

- ↑ Vipul v State of Uttar Pradesh, SLP (Crl.) No. 3114 of 2022, Supreme Court of India, judgment dated 5 August 2022 https://indiankanoon.org/doc/77984354/ accessed 15 October 2025.

- ↑ G Venkateshan v State, Madras High Court, judgment dated 8 August 2024, reported in (2024) Verdictum, https://www.verdictum.in/court-updates/high-courts/gvenkateshan-vs-the-state-plea-bargaining-non-gender-offences-plea-bargaining-1548613 accessed 15 October 2025.

- ↑ https://www.scconline.com/blog/post/2022/10/31/supreme-court-under-trial-prisoners-suggestions-plea-bargaining-probation-of-offenders-act-compoundable-offences-bail-dlsa-under-trial-review-committees-legal-resea/

- ↑ Legal Services of Maharashtra, “Plea Bargaining”, <https://legalservices.maharashtra.gov.in/Site/Upload/Pdf/plea-bargaining.pdf>

- ↑ https://www.legalserviceindia.com/legal/article-8436-plea-bargaining.html

- ↑ Legal Vidhiya, “Types of Plea Bargaining: Charge, Count, Fact, Sentence, etc.” https://legalvidhiya.com/plea-bargaining-2/ accessed 15 October 2025.

- ↑ https://www.legalserviceindia.com/legal/article-3857-concept-of-plea-bargaining-under-criminal-procedure-code.html

- ↑ The Legal Quotient, “Fact Bargaining… involves negotiations of factual version, sometimes criticized” https://thelegalquotient.com/criminal-laws/criminal-jurisprudence/plea-bargaining-in-india/3642/ accessed 15 October 2025.

- ↑ Code of Criminal Procedure 1973, ss 265A–265L (as inserted by the Criminal Law (Amendment) Act 2005).

- ↑ Code of Criminal Procedure 1973, s 320.

- ↑ State of Gujarat v Natwar Harchandji Thakor (2005) 1 SCC 189.

- ↑ Law Commission of India, Report No 142: Concessional Treatment for Offenders who on their own initiative choose to plead guilty without any bargaining (1991).

- ↑ Lindsey Devers, “Plea and Charge Bargaining”, Bureau of Justice Assistance U.S. Department of Justice, <https://bja.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh186/files/media/document/PleaBargainingResearchSummary.pdf>

- ↑ Latin term which means "i do not wish to contest".

- ↑ Wests Encyclopedia of American Law.

- ↑ Government of Canada, “Victim Participation in the Plea Bargaining Process in Canada”, <https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/cj-jp/victim/rr02_5/p0.html#:~:text=A%20simple%20definition%20of%20plea,action.%22%20More%20specifically%2C%20three>

- ↑ Government of Canada, “Victim Participation in the Plea Bargaining Process in Canada”, <https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/cj-jp/victim/rr02_5/p0.html#:~:text=A%20simple%20definition%20of%20plea,action.%22%20More%20specifically%2C%20three>

- ↑ Daniel Boffey, “Rise of plea-bargaining coerces young defendants into guilty pleas”, The Guardian <https://www.theguardian.com/law/2022/oct/06/rise-of-plea-bargaining-coerces-young-defendants-into-guilty-pleas-says-report>

- ↑ Criminal Justice Act 2003, s.144 (U.K.).

- ↑ Sentencing Council, Reduction in Sentence for a Guilty Plea: Definitive Guideline (Sentencing Council, 2017) https://www.sentencingcouncil.org.uk/overarching-guides/crown-court/item/reduction-in-sentence-for-a-guilty-plea-first-hearing-on-or-after-1-june-2017/ accessed 16 October 2025.

- ↑ Crown Prosecution Service, Sentencing – Overview of General Principles and Mandatory Custodial Sentences (CPS, 2022) https://www.cps.gov.uk/legal-guidance/sentencing-overview-general-principles-and-mandatory-custodial-sentences accessed 16 October 2025.

- ↑ John Baldwin and Mike McConville, ‘Plea Bargaining and Plea Negotiation in England’ (1979) 13 Law and Society Review 287; Sentencing Academy, Sentence Reductions for a Guilty Plea (Sentencing Academy, 2021) https://www.sentencingacademy.org.uk/sentence-reductions-for-a-guilty-plea/ accessed 16 October 2025.

- ↑ https://www.svpnpa.gov.in/static/gallery/docs/697450646409418c8f7c2c8d39576d85.pdf

- ↑ https://nja.gov.in/Concluded_Programmes/2022-23/P-1341_PPTs/2.Plea%20bargaining%20-%20Session%20IV.pdf

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 SVP National Police Academy, "Criminal Law Review 2021", Vol. 7 No.1, SVP National Police Academy, Hyderabad, <file:///C:/Users/J%20K%20Saxena/Downloads/CLR_2021_72RR%20(1).pdf>