Police custody

What is police custody?

A police custody[1] can be defined as an arrest of a person, suspected of having committed a cognizable offence, by a police officer. The term custody[2] here means apprehending someone for protective care. A police custody is when a police officer arrests the suspect of a crime, following some information/ complaint/ report of a crime. It is done with the intent of preventing him from committing further crimes.

Official definition of police custody

Police custody is not specifically defined under any statute, however, it finds its mention in the Bhartiya Nagrik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023 (BNSS), which recently replaced the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (CrPC).

As per Section 35(1)(b) of the BNSS and Section 41 of the CrPC, a police officer can arrest a person without an order from a Magistrate or a warrant, if a reasonable complaint has been made or credible information has been received, or a reasonable suspicion exists that he has committed a cognizable offence punishable with imprisonment for a term which may be less than seven years or which may extend to seven years whether with or without fine, if the following conditions are satisfied, namely:—

- the arrest is necessary to prevent further offence, and to conduct proper investigation, and prevent the person from making any inducements or threats to the court or police officer; or

- if the person is not arrested, their presence in the court cannot be ensured; or

- who has been proclaimed as an offender either under BNSS/ CrPC or by order of the State Government; or

- in whose possession anything is found which may reasonably be suspected to be stolen property; or

- who obstructs a police officer while in the execution of his duty, or who has escaped, or attempts to escape from lawful custody.

It is imperative that the police officer must record their reasons in writing when making the arrest. In cases where the arrest is not required, the reasons in writing must be recorded as well.

Types of police custody

As per Articles 22(1) and 22(2) of the Constitution of India, an arrested person must be made to appear before a magistrate within twenty-four hours of being taken into custody, with the right to counsel. Section 57 of the CrPC and Section 58 of the BNSS concurs that a person detained cannot be kept in police custody for more than twenty-four hours, without an arrest warrant.

The standard rule: detention upon the approval of the magistrate

The BNSS and CrPC mention the responsibilities of a magistrate while allowing for police custody in Sections 187(4) and 167(2)(ii)(b) respectively. It states that a magistrate shall not authorize the detention of an accused in police custody unless the accused is made to appear before him, for the first and every subsequent time. A caveat is further mentioned that the Magistrate authorizing detention in the custody of the police shall record his reasons for doing so.

Section 167(1) of the CrPC and Section 187(2) of the BNSS further add to the mandate by allowing a person to be detained in judicial custody if the investigation cannot be completed within the twenty-four hour period. The officer in charge of the police station or the police officer making the investigation must transmit the entries to the nearest Judicial Magistrate, who may authorize the detention for up to fifteen days. If the Magistrate has no jurisdiction to try the case, they may order the accused to be forwarded to a Magistrate with such jurisdiction. However, no Magistrate can authorize detention beyond fifteen days unless adequate grounds exist. The accused person is subject to judicial custody for a period of ninety days for offences punishable by death, life imprisonment, or ten years, or sixty days for other offences. If the accused person is prepared to provide bail, they can be released on bail, on the expiry of the said period of ninety days, or sixty days, as the case may be. Magistrates cannot authorize detention in police custody without the accused being presented in person, and no Magistrate of the second class, not specially empowered by the High Court, can authorize detention in police custody.

In the case of Mithabhai Pashabhai Patel and Ors. v. State of Gujarat, 2009[3], the court had held that an accused who has been granted bail cannot be taken into police custody for further investigation unless the bail is cancelled.

Provisions in special legislations

However, the standard rule of detention finds its exceptions in the special legislations.

The Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967 (UAPA)

The UAPA has modified certain provisions of the CrPC, allowing every offence punishable under the UAPA Act to be a cognizable offence. As per Section 43D of the UAPA, Section 167 of the CrPC applies to cases involving UAPA, with alterations to ‘fifteen days’, ‘ninety days’, and ‘sixty days’ period construed as ‘thirty days’, ‘ninety days’, and ‘ninety days’ respectively. If investigations are not completed within the ninety-day period, the court, after being satisfied with the report produced by the Public Prosecutor, may extend it up to 180 days.

The apparent issue with this special legislation is that instead of meeting the promises of greater efficiency and a timely police investigation, it increases the concerns of the people detained by the police as the duration of their custody increases.

Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act 2015

There are also situations where the alleged offender is apprehended by the police but is not ‘arrested’ or kept in ‘police custody’.

Section 10(1) and Section 12 of the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act 2015, when read together state that if a child is apprehended, they must be placed under the charge of a special juvenile police unit or designated child welfare police officer. The child must be produced before the Board within twenty-four hours, excluding the time for the journey. Provided that in no case, a child alleged to be in conflict with law shall be placed in a police lockup or lodged in a jail.

Bail can be granted to a child alleged to have committed a bailable or non-bailable offence, unless there are reasonable grounds to believe it could bring them into association with a known criminal or expose them to moral, physical, or psychological danger. If the child is not released on bail, they must be kept in an observation home or place of safety until brought before the Board. If the child fails to meet the conditions of bail within seven days, they must be produced for modification.

The Police Act, 1861

As per Section 34 of the Police Act, 1861, the State Government has extended penalties and enhanced the powers of the police officers for certain offences on roads and open places within towns. Any person who commits any of these offences, such as slaughtering cattle, cruelty to animals, obstructing passengers, exposing goods for sale, throwing dirt into the street, being drunk or riotous, indecent exposure of person, or neglect to protect dangerous places, shall be liable to a fine of fifty rupees or imprisonment for up to eight days. Police officers can take into custody without a warrant for any person who commits these offences. Penalties for neglect of duty include three months’ pay or imprisonment for up to three months, with or without hard labor. This section empowers police officers to take into custody any person who commits these offences without a warrant.

Issue with prolonged duration of police custody

With prolonged police custody, the possibility of custodial violence is increased, which is an important concern[4]. Prolonged police custody makes the accused more susceptible to coerced admissions and other forms of evidence falsification.

The collection of forensic evidence is a further source of concern. Prior to the BNSS, when there was an unreasonable delay in submitting samples to forensic labs or problems with sealing after collection, courts rejected the forensic evidence. However, now if the accused is given unlimited access through police custody in the later stages, the BNSS would make such tampering easier.

In CBI v. Anupam J. Kulkarni, 1992,[5] and Devender Kumar & Anr Etc vs State Of Haryana & Ors.[6], the courts had to decide whether or not a person could still be remanded to police custody by the magistrate who produced him after the first fifteen-days had passed. The courts held that even if subsequently it is discovered that he committed further yet less serious offences during the same transaction, there cannot be any further detention in police custody beyond the initial fifteen days. However, if the detained accused is a party to another case that results from a different transaction, this bar does not apply.

Police Custody at the Stage of Further Investigation

Police remand can be sought in respect of accused arrested at the stage of further investigation, if interrogation is necessary. The expression ‘accused if in custody’ in Section 309(2) of the CrPC does not include the accused who is arrested on further investigation before a supplementary charge sheet is filed.

In the case of Dinesh Dalmia v. CBI[7], the court held that an accused should not be sent to judicial custody under 167(2) CrPC, but rather under 309(2) CrPC when the police custody has expired.

In the case of State v. Dawood Ibrahim Kaskar[8], the court ruled that detention in custody under Section 167 of the CrPC and the remand of a person under Section 309(2) of the CrPC vary significantly. A person may be placed in judicial custody under Section 309(2), which applies only after the court has given the case its proper consideration. However, a person may be placed into custody while an investigation is ongoing under Section 167. Based on the specifics of the case and the magistrate’s order, custody may be either police or judicial[9].

Alteration of Police custody and Judicial custody

The phrase “from time to time” included in S. 167(2) indicates that, within the first 15 days of custody, multiple orders may be issued under S. 167(2), changing the type of custody from judicial to police and vice versa. However, after the fifteen days, only judicial custody may be used as a form of custody.

This change in custody may be the result of one order, or several orders if the orders are for a shorter period of time; nonetheless, the total amount of time in custody cannot exceed fifteen days.

Official Documents

There have been various reports by law commissions and human rights organizations that time and again advocate for the cause of both the detained persons as well as the victims.

The Malimath Committee Report[10] suggested doubling of both the ninety-days period available for filing a charge-sheet after which an accused can be released on bail, and the permissible fifteen-days police remand of an accused for grave offences. It also recommended the following for the purposes of Police inquiry:

- Law and Order should be separated from its Investigation branch;

- state Security Commissions and a National Security Commission should be formed;

- specialized squads should be established to combat organized crime; and they should be assembling a group of officers to investigate interstate or transnational crimes; and

- police custody should be extended to thirty days and an extra ninety days period should be allowed to file charge sheets in cases of major crimes.

The Committee took a stern stand for the protection of the victims, but these recommendations have not been implemented yet.

On the other hand, the NHRC guidelines focus on the rights of the detained individuals, and states that arrest is a curtailment of the fundamental human rights, and hence, there are certain thresholds that must be met. For instance, first, at the stage of pre-arrest, an arrest can be made without a warrant only if the police are satisfied with the genuineness of the complaint. This was highlighted in the case of Juginder Kumar v. State of Uttar Pradesh, 1994[11]. Then second, at the time of arrest, the following steps shall be taken:

- Use of force is to be avoided;

- handcuffing is to be avoided;

- searches on the person of the accused should be done in a dignified manner;

- as far as possible, women police officers should be present at the time of arrest of women;

- during the arrest of children or juveniles, no use of force is permitted under any circumstances; and

- the arrested person should be informed of his right to inform a friend, right to legal counsel and aid, and right to medical assistance.

Third, post his arrest, the person should be produced before a magistrate within twenty-four hours.

Moreover, as per the guidelines framed by NALSA, known as “The Standard Operating Procedure for Under-Trial Review Committees”, constituted by the Ministry of Home Affairs states that there shall be a consideration of the cases of inmates who have completed half of their sentence, for their early release. This was in furtherance of the issue of overcrowding of Indian prisons.

Despite such efforts and recommendations in place, and even after 15 years of the enactment of the Model Police Act, 2006, only 17 states have adopted the Model Police Act or amended the state’s law in adherence to the Model law. Thereby, the Ministry of Home Affairs, under its 237th report, on the subject of “Police-training, Modernisation and Reforms”, has urged all the remaining states to express their concerns and come up with potential solutions such that a coherent and uniform police structure be maintained in India.

Regional Variations

As per the Model Police Manual, there are certain rules to be followed regarding Police Custody. It includes:

- all the detained arrested persons should be kept in secure areas under constant watch;

- people called to a police station for questioning should not be kept in lock-up without arrest;

- arrested persons known as goondas, rowdies, dangerous criminals, members of organized gangs, terrorist groups, or those likely to escape should be kept in lock-up rooms;

- they should not be able to leave the lock-up after sunset except in special circumstances with adequate escort;

- prior to remand, arrested persons should have the right to see relatives and an advocate, but they cannot talk to the public; and

- Food is provided at the government’s cost, and foreigners can communicate with their country’s representatives.

Appearance in official databases

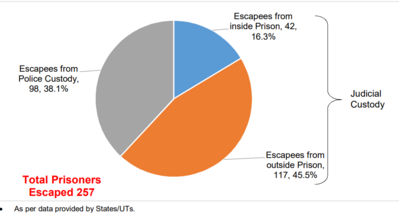

The National Crimes Records Bureau (NCRB) provides the following data, with regards to the statistics for Jail-Breaks, Escapes, and Clashes/Group Clashes inside the Prison. In the year 2022:

- 257 inmates managed to escape. Out of these, 98 (38.1%) had escaped from police custody and 159 from court custody.

- 113 individuals who had escaped were apprehended again.

- There were four instances of jail break.

- There were 45 incidents of conflicts or group conflicts in 2022.

Research that engages with police custody

The Polis Project: The plight of Kashmiris detained under the Jammu & Kashmir Public Safety Act (PSA)[12] highlights the plight of the Kashmiris.

A person may be detained in order to prevent them from acting in a way that could jeopardize “the security of the state or the maintenance of the public order” in accordance with the PSA, 1978. It has a striking resemblance to the National Security Act, which other state governments employ for detention without trial. In August 2023, the Jammu and Kashmir Home Department released a statement stating that 408 people who were detained under the PSA were being held in jails outside of Jammu and Kashmir. Since they were taken into custody following the loss of Article 370 and 35A and the abrogation of Jammu and Kashmir’s special status, they frequently endure arbitrary incarceration.

A Right To Information request made in 2020 by two students from Kashmir University brought attention to the issue of Jammu and Kashmir’s overcrowded jails. According to the data, there were 4,031 inmates housed in fourteen jails, which is more than the 3,600 maximum that was set. The problem was confirmed by later NCRB statistics from 2022, which revealed that 4,105 inmates were housed in the 14 facilities, more than the 3,600 maximum.

Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International India, and the International Commission of Jurists have all declared that the PSA ought to be revoked since it contravenes international norms pertaining to due process.

Also known as

Remand to police custody under section 167 CrPC is a delicate issue that involves a police investigation and should not be handled carelessly. It is sometimes necessary for the investigating officers to place the accused person under police remand in order to advance the case through appropriate questioning. This is because it is extremely difficult to conclude an investigation or interrogation within a twenty-four hour period, and the police are not allowed to hold an accused person in their custody for longer than twenty-four hours without a magistrate’s order.

Detention[13] entails holding an accused person in police custody without a valid justification to make an arrest. Laws stipulate requirements that must be fulfilled before an individual can be placed under arrest. People may be detained only under extraordinary circumstances, but detentions in other situations are considered to be illegal.

References

- ↑ Custody, Arrest, Judicial Custody and Police Custody, Vidhi Judicial Academy, https://vidhijudicial.com/custody,-arrest,-judicial-custody-and-police-custody.html

- ↑ Judicial Custody and Police Custody-Recent Trends, https://districts.ecourts.gov.in/sites/default/files/fct.pdf

- ↑ Mithabhai Pashabhai Patel & Ors vs State Of Gujarat, 2009 AIR SCW 3780, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/475211/

- ↑ Criminal Law Bills 2023 Decoded #15: Custody of Arrested Persons During Investigation, Nov. 14, 2023, https://p39ablog.com/2023/11/criminal-law-bills-2023-decoded-15-custody-of-arrested-persons-during-investigation/

- ↑ Central Bureau Of Investigation vs Anupam J. Kulkarni 1992 AIR 1768, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/244622/

- ↑ Devender Kumar & Anr vs State Of Haryana & Ors. 2010 AIR SCW 4411, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/244622/

- ↑ Dinesh Dalmia vs C.B.I on 18 September, 2007,https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1128468/

- ↑ State Through Cbi vs Dawood Ibrahim Kaskar & Ors, 1997, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1519516/

- ↑ Judicial Custody vs Police Custody, May 18, 2022, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1519516/

- ↑ Malimath Committee - An Overview, https://byjus.com/free-ias-prep/malimath-committee/

- ↑ Joginder Kumar vs State Of U.P 1994 AIR 1349, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/768175/

- ↑ Geographical Displacement and Medical Negligence: The plight of Kashmiris Detained Under the Public Safety Act, https://www.thepolisproject.com/read/geographical-displacement-and-medical-negligence-the-plight-of-kashmiris-detained-under-the-public-safety-act/

- ↑ Detention, https://byjus.com/question-answer/detention-is-the-act-of-keeping-an-accused-under-police-custody-legallyunlawfullylawfullyconstitutionally-1/