Political parties

What is a Political Party

A Political Party fundamentally represents an organised group of individuals who share similar political aims and opinions, seeking to influence public policy by getting their candidates elected to government office. They serve as essential institutional mediators, connecting civil society's demands to governmental machinery, thereby making modern representative democracy functionally possible. Their most publicly visible role, though not their only function, remains the nomination and presentation of candidates in electoral campaigns.

Official Definition of Political Party

Legislative definitions surrounding political parties are precise, establishing their status for regulatory and electoral purposes. While the general meaning describes a broad political organisation, the legal framework provides a strict definition for recognised electoral participation. Specifically, the Election Symbols (Reservation and Allotment) Order, 1968, defines a political party strictly as an "association or body of individual citizens of India registered with the Commission as a political party under Section 29A of the Representation of the People Act, 1951" (Section 2(h)).

This definition is crucial as it anchors all privileges and regulations to the process of registration under RPA, 1951, Section 29A. The legislative scope governing political parties is layered across several key statutes. The Constitution of India (Article 324) grants the Election Commission of India (ECI) the foundational authority to regulate party activities. The Representation of the People Act, 1951 (RPA, 1951), provides the framework for party registration (Part IVA), candidate nominations (Part V), and corrupt practices (Part VII). Finally, the Election Symbols (Reservation and Allotment) Order, 1968, promulgated under the authority of the Constitution and the RPA, defines the rules for party recognition and the exclusive allotment of symbols.

The operation of political parties is governed by several critical legal provisions that mandate transparency and establish boundaries for conduct:

Freedom of Association

The right to form a political party finds its fundamental guarantee in Article 19(1)(c) of the Constitution of India. This constitutional bedrock allows citizens to organize themselves for political action, though this freedom is subject to reasonable restrictions.

Anti-Defection

This constitutional provision acts as a regulatory check, enshrined in the Tenth Schedule of the Constitution. Its purpose is to reinforce party discipline by penalizing elected legislators for voluntarily giving up party membership or voting against the party whip. This mechanism effectively prioritizes party loyalty and mandate over individual legislative conscience.

Registration of Political Party

The core legal identity is established by Registration under the Representation of the People Act, 1951 (RPA, 1951), Section 29A. This voluntary process is mandatory for any association seeking to contest elections. The party’s constitution must explicitly affirm its true faith and allegiance to the Constitution of India and the principles of socialism, secularism, and democracy. Registration grants the party legal recognition and access to electoral privileges

Recognition of Political Party

Recognition is the grant of status (National or State Party) by the ECI based on a party’s quantifiable poll performance (votes polled and seats won). The criteria are strictly detailed in Paragraphs 6A and 6B of the Election Symbols (Reservation and Allotment) Order, 1968. Recognition is essential for securing a reserved symbol and accessing privileges like free broadcast time.

De-recognition of Political Party

De-recognition occurs when a recognized party fails to maintain the performance criteria. The Symbols Order, 1968, Paragraph 16A, grants the ECI the power to suspend or withdraw recognition for failure to observe the Model Code of Conduct or follow lawful directions. However, the ECI lacks the statutory power under the RPA, 1951, to de-register (cancel registration) of a political party for non-compliance (e.g., failure to contest elections), a limitation confirmed by the Supreme Court in the Indian National Congress vs. Institute of Social Welfare case.

Internal Democracy

While RPA Section 29A requires parties to submit their constitution containing details on the election of office-bearers and adherence to democratic spirit, the Act does not confer supervisory jurisdiction upon the ECI to enforce or adjudicate the fairness of internal elections once a party is registered. This legal gap often renders the democratic provisions in party constitutions merely formal, not functional.

Auditing Finances

Financial transparency is statutorily mandated. Parties must submit Contribution Reports to the ECI detailing donations received in excess of $20,000. Audited Accounts: The ECI mandates the submission of Annual Audited Accounts to comply with Section 13A of the Income Tax Act, 1961. Proper auditing is viewed as critical to the conduct of free and fair elections.

Political Party as Public Authority under the RTI Act

The Central Information Commission (CIC) Full Bench ruled in 2013 that major political parties (including INC and BJP) are 'Public Authorities' under Section 2(h) of the RTI Act, 2005. This declaration was justified by the critical public functions they discharge and the substantial indirect financing they receive from the government (e.g., tax exemptions).[1] Th decision is challenged and pending final adjudication at the Supreme Court.

Election Symbol

This Election Symbol Order, 1968 made by the Election Commission of India under its constitutional and statutory powers (Art. 324 of the Constitution read with Section 29A of the Representation of the People Act, 1951), lays down rules for how election symbols are specified, reserved, chosen and allotted in Parliamentary and State assembly elections.

Parliamentary Committees

Political parties are the determinant factor in the composition of Parliamentary Committees, which are essential for detailed scrutiny of legislation and administration. The membership of parliamentary committees (both Standing Committees and Ad Hoc Committees like Joint Parliamentary Committees or JPCs) is generally determined on the principle of proportionality to reflect the numerical strength of different political parties in the House. The Speaker of the Lok Sabha or the Chairman of the Rajya Sabha nominates members to these committees, but they do so based on the recommendations or allocation slots provided by the political parties and groups. This party-driven composition ensures that bills receive detailed scrutiny from members across the political spectrum. Parties often use these assignments to align an MP's personal expertise and interests with the relevant committee's scope.

Political Party as Parliamentary Groups

The recognition of political parties as distinct units within India’s parliamentary framework is primarily governed by the Rules of Procedure and Conduct of Business in both the Lok Sabha and the Rajya Sabha, alongside supplementary “Directions” issued by the respective presiding officers. This recognition holds procedural significance as it determines a party’s eligibility for participation in parliamentary business, allocation of time, representation on committees, and access to institutional facilities.

Recognition under the Lok Sabha Rules

The Rules of Procedure and Conduct of Business in Lok Sabha[2] continue to serve as the operative framework as of 2024[3]. While the Rules do not explicitly define the term political party, they acknowledge legislature parties through procedural requirements. Rule 2 provides general definitions of “member” and “House” but omits any numerical or structural definition of political parties[4]. The recognition of political units is instead facilitated through the Directions by the Speaker, issued under the Speaker’s discretionary powers, which determine the status of a party or group for purposes such as representation and speaking rights[5].

Appendix IV of the Rules requires the leader of every legislature party consisting of more than one member to submit a formal list of its members, a copy of the party’s constitution, and any rules applicable to its legislature wing (Lok Sabha Secretariat, 2019). This procedure affirms that political parties are treated as organizational entities within the parliamentary system, possessing formal leadership structures and codified internal regulations. Furthermore, Appendix II to the Rules includes the Leaders of Recognized Parties and Groups in Lok Sabha as members of the General Purposes Committee, demonstrating the procedural entrenchment of recognized political units in parliamentary administration (Lok Sabha Secretariat, 2019). However, the recognition criteria remain flexible and are largely determined by the Speaker’s Directions rather than a codified numerical formula, allowing for adaptability to shifting political configurations[6].

Recognition under the Rajya Sabha Rules

The Rules of Procedure and Conduct of Business in the Council of States (Rajya Sabha) adopt a more structured approach to recognition through Rule 266 and the accompanying Chairman’s Directions. Chapter 10 of the Rajya Sabha at Work elaborates on the recognition of parliamentary parties and parliamentary groups[7] . A parliamentary party must possess a distinct ideology, a common parliamentary programme, an organizational structure both inside and outside Parliament, and a minimum strength of one-tenth of the total membership of the House. In contrast, a parliamentary group must meet similar organizational and ideological conditions but with a minimum strength of fifteen members. Recognition is conferred by the Chairman, whose decision on such matters is final.

These provisions ensure that only cohesive political entities with demonstrable ideological unity and organizational capability are granted formal recognition. This status allows recognized parties and groups to exercise procedural privileges, including participation in committee representation, allocation of office space, and entitlement to special facilities under the Leaders and Chief Whips of Recognized Parties and Groups in Parliament (Facilities) Act, 1998[8] [9].

Political Party as defined in Government Reports

Goswami Committee (1990):

The Dinesh Goswami Committee on Electoral Reforms was constituted in 1990 under the Chairmanship of the then Law Minister, Mr. Dinesh Goswami, by the V.P. Singh government. The committee was tasked with suggesting comprehensive measures to eradicate flaws threatening the integrity of the electoral system, such as the increasing role of money and muscle power, criminalization of politics, and misuse of official machinery.

The report made extensive recommendations spanning the electoral machinery, political parties, and state funding. The Committee recommended that the Chief Election Commissioner (CEC) should be appointed by the President after consulting with the Chief Justice of India and the Leader of the Opposition. Further, the other Election Commissioners should be appointed in consultation with the CEC, and all EC members should be ineligible for further government appointments upon the end of their tenure, thereby securing the independence of the commission. To enhance procedural integrity, the Committee suggested implementing multi-purpose Photo Identity Cards (ID Cards) for voters. It also advocated for the statutory backing of the Model Code of Conduct (MCC), banning the use of government resources in campaigns, and making legislative measures to deal with endemic problems like booth capturing and rigging.

Crucially, the committee was an early proponent of the extensive use of Electronic Voting Machines (EVMs) to stop manipulation and tampering. The report recommended increasing the security deposit for both Lok Sabha and Assembly elections. Furthermore, it proposed a restriction banning a candidate from contesting elections from more than two constituencies. A major focus was on party financing: the committee recommended enacting comprehensive legislation to govern the registration and de-recognition of political parties, making the compulsory maintenance and audit of party accounts mandatory. It suggested that parties should be required to disclose their annual accounts to the income-tax authority. The committee also initiated the push for mandatory disclosure of criminal antecedents of candidates and their dependents, alongside their assets and educational qualifications, which has since become judicially enforced.

Recognizing that high election expenditure was a source of corruption, the Goswami Committee endorsed the idea of State Funding of Elections. This funding was suggested in kind (such as time on electronic media, printing facilities, and vehicles/petrol) rather than cash, and would be made available to candidates of political parties recognized by the EC. The aim was to reduce reliance on private, often opaque, donations and thereby curb the influence of money power.

Law Commission's Report

Law Commission's 170th Report (1999): Reform of the Electoral Laws.

This comprehensive report aimed to make the electoral system more representative, fair, and transparent. The Commission suggested including a chapter in the law dedicated to regulating the formation and functioning of political parties, specifically to ensure internal democracy. It proposed making it obligatory for every candidate to declare their assets (including those of a spouse and dependents) and particulars regarding criminal cases pending against them directly in the nomination paper. This proposal predated and provided the blueprint for the Supreme Court's mandate on candidate disclosure. The report put forth draft Bills, including one for amending the Representation of People Act, 1951.

Law Commission's 244th Report (2014): Electoral Disqualifications.

This report focused on curbing the criminalization of politics, addressing the ineffectiveness of the then-existing law (disqualification only upon conviction) due to long trial delays. It recommended that disqualification should be triggered at the stage of framing of criminal charges by a competent court for serious offences (punishable by five years or more), rather than waiting for conviction. It also recommended that the penalty for filing a false affidavit (RPA Section 125A) be enhanced to a minimum of two years imprisonment, and that conviction for this offense should explicitly be made a ground for disqualification.

Law Commission's 255th Report (2015): Electoral Reforms

This report provided comprehensive suggestions to improve election management, candidate financing, and party regulation. It supported empowering the ECI with the authority to de-register political parties for non-compliance, a power the ECI had long sought.

National Commission to Review the Working of the Constitution Report (2001):

The National Commission to Review the Working of the Constitution examined the structure and functioning of political parties, highlighting the need for internal party democracy and anti-defection measures. Its work focused on structural requirements for parties and strengthening the Anti-Defection Law.

Tarkunde Committee (1975):

Formed under the chairmanship of Justice V. M. Tarkunde, this was one of the earliest official committees dedicated to electoral reform. Its recommendations were instrumental in pushing for the lowering of the voting age (which was later achieved by the 61st Amendment Act, 1988) and introducing state funding of elections.

Political Parties as defined in Official Reports

Political Parties (Maintenance and Auditing of Accounts) Bill, 2010

The Political Parties (Maintenance and Auditing of Accounts) Bill, 2010, which was introduced in Rajya Sabha as a Private member bill by Shri Mohan Singh. This bill seeks to provide for preparation, maintenance and auditing of annual accounts of political parties.

According to this bill

Political party means an association or body of individual citizens of India registered with the Commission as a political party in accordance with the provisions contained in Section 29A of the Representation of the People Act, 1951.

The Political Parties (Maintenance and Auditing of Accounts) Bill, 2010 aimed to promote transparency and accountability in the financial affairs of political parties. It requires all registered political parties to maintain proper annual accounts of income and expenditure, have them audited by a qualified Chartered Accountant, and submit the audited reports to the Election Commission of India, which will publish them for public access. Non-compliance can lead to suspension or withdrawal of a party’s registration or recognition. The Bill empowers the Central Government to make rules in consultation with the Election Commission and gives the Act overriding authority over conflicting laws, thereby seeking to curb money power and ensure financial transparency in politics.

Political Parties as defined in International Instruments

African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance

The African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance recognizes political parties as vital pillars of democracy. It emphasizes pluralism, free competition , strengthening party systems, and protecting opposition parties, which are all critical to ensuring democratic governance in AU member states.

Inter-American Democratic Charter

The Inter-American Democratic Charter recognizes political parties and political organizations as essential components of a functioning democracy. It emphasizes the need for a pluralistic party system, ensuring that citizens have real choices and the ability to participate freely in political life. The Charter also highlights the importance of transparency in party financing and the equitable participation of parties in elections, reinforcing the role of political parties in upholding democratic governance, accountability, and the rule of law across the Americans.

Commonwealth Charter

The Commonwealth Charter affirms the fundamental right of individuals to participate in democratic processes, especially through free and fair elections. It emphasizes that governments, political parties, and civil society share the responsibility of upholding and promoting democratic values and practices. These entities are expected to act accountably and foster a political culture that supports active citizen engagement and transparent governance.

OSCE Guidelines on Political Party Regulations (2010)

The OSCE Guidelines on Political Party Regulations (2010) emphasises that political parties must practice internal democracy through transparent leadership selection and active member engagement. They should ensure financial transparency to combat corruption and guarantee equitable media access during elections. Political parties are encouraged to promote inclusiveness by facilitating the participation of women, minorities, and youth. While state regulation is necessary to prevent abuse, it must not undermine party independence or impose excessive restrictions. The freedom to form and operate political parties without undue interference is essential for a robust democratic system, fostering fair competition and strengthening democratic governance.

Joint Guidelines on Political Party Regulation (2020)

The Joint Guidelines on Political Party Regulation (2020) emphasise that political parties are central to democratic life, serving as the bridge between citizens, public debate, and power. It outlines that parties must be regulated in ways that guarantee their freedom to form, operate and campaign, while ensuring transparency, accountability (especially in financing), internal democracy and integrity. At the same time, it underscores that regulation should facilitate pluralism, prevent dominance by a single party, and maintain fair competition, so that parties contribute to democratic elections, representation and governance under the rule of law.

Political party as defined in Case Laws :

Gajanan Krishnaji Bapat and Anr v. Dattaji Raghobaji Meghe and Ors (1995)

The Supreme Court in this case upheld the election of the returned candidate, Dattaji Raghobaji Meghe, by ruling that the petitioners failed to discharge the heavy burden of proof required to establish the corrupt practice of incurring excess expenditure under the RPA, 1951.[10]

The petitioners, in this case, alleged that the winner had suppressed election expenses, falsely showing them as incurred by his political party or other associations to circumvent the prescribed expenditure limit.

The Hon’ble SC’s held that:

- Corrupt practices must be proved with evidence as clear, cogent, and reliable as in criminal charge.

- The mere possibility or suspicion that the candidate funded the expenses shown in the name of a party or association is not enough.

- The petitioners failed to conclusively prove that the expenses were authorised or incurred by the candidate or his election agent.

Indian National Congress (I) v. Institute of Social Welfare and Ors (2002)

The Supreme Court dealt with the question whether the Election Commission of India (ECI) have the power under Section 29A of the RPA, 1951 to de-register or cancel the registration of a political party[11].

The Court held that :

- ECI's function is Quasi - Judicial : The Court held that the ECI’s function of registering a political party under Section 29A is quasi- judicial because it requires the commission to consider facts, conduct an inquiry, and provide an opportunity for a hearing before deciding.

- No General De-registration Power : The ECI does not have an express or inherent general power to de-register a political party for violating the Constitution or breaching its commitment ( like calling for unconstitutional bundhs enforced by force, which was the issue in this case ).

- Ancillary Power for De-registration : The Court ruled that the ECI possesses incidental and ancillary power to cancel a registration in three exceptional circumstances:

- Where the registration was obtained by fraud or forgery.

- Where the party amends its internal documents to abrogate its commitment to the Constitution of India, secularism, democracy, or sovereignty/integrity of India (thus knocking out the very foundation of its registration).

- Where a registered political party is declared unlawful by the Central Government under laws like the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967.

Union of India v. Association for Democratic Reforms (2002)

The Supreme Court emphasised on the electorate’s right to information and held that it strengthens the democratic fabric by ensuring that voters are empowered to make informed decisions.[12]

Technological and Digital Initiatives :

Registration of political parties is governed by the provisions of Section 29A of the Representation of the People Act, 1951. An association seeking registration under the said Section has to submit an application to the Commission within a period of 30 days following the date of its formation, as per the guidelines prescribed by the Commission in exercise of the powers conferred by Article 324 of the Constitution of India and Section 29A of the Representation of the People Act, 1951.

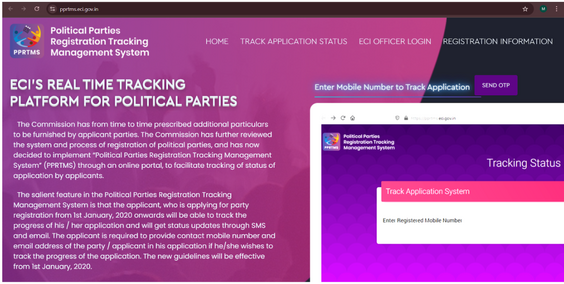

In order to enable applicants to track the status of the application, the Commission has launched a “Political Parties Registration Tracking Management System(PPRTMS)”. The salient feature in the PPRTMS is that the applicant, who is applying for party registration from 1st January, 2020 will be able to track the progress of his/her application and will get status update through SMS and e-mail. The status can be tracked through the Commission’s portal at link https://pprtms.eci.gov.in/ . The Commission in the month of December, 2019, has amended the guidelines and issued a Press Note dated 02.12.2019 regarding registration of political party for the information of the general public. The new guidelines is effective from 1st January, 2020 and is available on the Commission’s website http://eci.gov.in. [13]

Official Database:

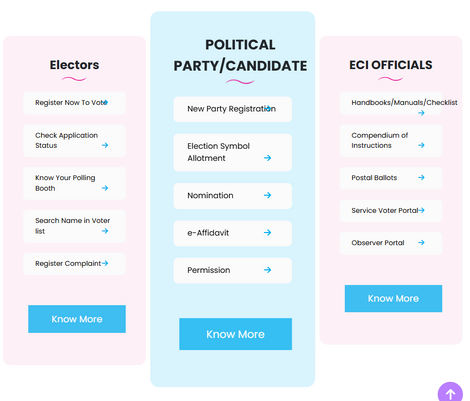

The Election Commission of India

The website eci.gov.in is the official portal of the Election Commission of India (ECI), a constitutional body established under Article 324 of the Indian Constitution responsible for conducting and supervising elections to the Parliament, State Legislatures, and the offices of the President and Vice-President of India. It serves as the primary digital platform for disseminating authentic information related to elections, including voter registration, electoral rolls, candidate affidavits, election schedules, results, and press releases. The portal also provides access to historical election data, guidelines for political parties, the Model Code of Conduct, and voter education resources under initiatives such as SVEEP (Systematic Voters’ Education and Electoral Participation). By integrating technology into electoral processes, the website enhances transparency, accessibility, and public participation, allowing citizens to verify their voter details, download electronic voter ID cards (e-EPIC), and track election updates in real time. Despite its significance as a symbol of democratic transparency, the site has occasionally faced issues such as server downtime, interface inefficiency, and user-reported glitches during peak election periods. Nevertheless, eci.gov.in remains a vital instrument in promoting free and fair elections, strengthening electoral integrity, and fostering informed civic engagement across India’s democratic framework.

Repository of Constitution of Political Parties

The ECI’s Constitution of Political Party page outlines the requirement that any political party seeking registration with the ECI must submit its own party constitution/memorandum or rules and regulations as part of the registration process under Representation of the People Act, 1951 (Section 29A). Key features that such a party constitution typically must include are :

- The party’s name

- Objectives/aims

- Organizational Structure

- Offices at national/state/district levels,

- Provisions for membership,

- Elections of office‑bearers,

- Terms of office,

- Procedure for amendment of constitution,

- Mechanisms for merger/dissolution, and

- obligations to bear true faith and allegiance to the Constitution of India and to uphold the unity, integrity and sovereignty of India.

The ECI expects these documents to reflect internal democracy and transparency in party functioning. Although the ECI monitors submission of these documents at registration time, recent judicial pronouncements have held that the ECI does not have supervisory jurisdiction to enforce whether a registered party is actually adhering to its submitted constitution in its internal functioning.

Organisational Election

The ECI’s page on Organisational Elections sets out the requirement that registered political parties hold periodic internal elections for their leadership and office-bearers, as part of fulfilling their obligations under registration rules. The purpose is to ensure that political parties are not static hierarchical structures but evolving, democratically run organisations with transparent processes for selecting their leadership. These elections promote internal accountability, member participation, and alignment with democratic values. By mandating such internal democracy, the ECI intends to improve the overall health of party-politics and strengthen the link between citizen-members and the party structure.

Database maintained by Civil Societies

Association for Democratic Reforms

The ADR report offers a comprehensive analysis of the status, finances, and activity of Registered Unrecognised Political Parties in India.

Another ADR report comprehensively gives out the status of Information that political parties should disclose in Public Interest.

International Experience:

Germany

Germany is famous for making internal democracy a constitutional requirement. Its laws make sure political parties hold regular elections, involve members in decision-making, and are transparent about finances. Parties get public funding, but only if they report all donations and spending. This system is highly transparent and accountable. Strong legal rules ensure parties are truly democratic inside and financially transparent.[14]

Portugal

Portugal emphasizes participation. Every party must have written rules explaining how members can vote, choose leaders, and help shape policies. Public funding is linked to election results, and annual audits ensure money is spent properly. Clear rules for member participation and responsible funding make parties accountable and fair.[15]

Spain

Spain requires parties to be democratic and ensures members can influence leadership and candidate selection. Its Court of Audit checks party finances, making sure donations and spending are transparent. Combines member participation with independent financial oversight.[16]

Latin America

Many countries, like Mexico, Chile, and Costa Rica, give parties public funding tied to election results. They also require internal elections and leadership rotation. Enforcement isn’t perfect, but public funding helps reduce dependence on private donors and encourages fair competition. Public funding ensures equality and limits corruption.[17]

Sub-Saharan Africa

Countries like South Africa, Kenya, and Ghana have laws protecting party formation and requiring registration with independent election commissions. Public funding exists in some countries, and commissions audit finances. Enforcement can be tricky, but systems are improving. Independent electoral commissions ensure parties follow rules and remain accountable.[18]

Research

Constitutional Particracy: Political Parties and the Indian Constitution

This paper by Aradhya Sethia, affiliated with the University of Cambridge, Faculty of Law, and the Honourable Society of the Inner Temple, was first posted on July 12, 2024, and last revised on July 15, 2025. It is a conceptual and constitutional analysis rather than an empirical study, developing the theory of constitutional particracy to explain how political parties are not merely external political actors but are deeply embedded within and constitutive of India’s constitutional framework. Through a normative and interpretive approach, the author argues that political parties, by shaping electoral processes, government formation, law-making, and accountability, have effectively reallocated real constitutional power from formal state institutions to themselves. This dynamic, often viewed as manipulative of constitutional formalities, is reframed by Sethia as a source of vitality and functionality within India’s pluralist democracy. The paper contends that parties are “intimate yet invisible friends” of the Constitution and urges a reassessment of legal doctrines concerning defection laws, intra-party democracy, and the constitutional role of opposition parties. By highlighting the structural centrality of parties, Sethia’s framework recommends that constitutional and legal discourse formally recognize the phenomenon of constitutional particracy to better align normative theory with India’s political reality.[19]

Where’s the Party?: Towards a Constitutional Biography of Political Parties in India

This paper by Aradhya Sethia, affiliated with the University of Cambridge, Faculty of Law and the Honourable Society of the Inner Temple, was first posted on November 18, 2018, and last revised on November 5, 2019. Adopting a constitutional-theoretical and doctrinal methodology, the paper traces the historical and constitutional evolution of political parties in India, examining how they were perceived during the framing of the Constitution and how their role has transformed through subsequent constitutional and legal developments, especially the anti-defection law. Sethia introduces the idea of a “constitutional biography” of parties to demonstrate that, although the Indian Constitution does not expressly mention political parties, they have become indispensable to its operation and democratic legitimacy. The paper argues that parties have been “constitutionalized” over time to stabilize governance, shape representation, and manage political competition, while also critiquing the inconsistencies in Indian electoral and constitutional jurisprudence—where anti-defection law recognizes parties as core representative institutions, but election law continues to emphasize individual candidates. Sethia concludes that acknowledging this duality is essential for coherent legal treatment of political finance, accountability, and party regulation in India’s constitutional democracy.[20]

Public Functions of Political Parties in the United Kingdom

This paper by Leah Trueblood, published in the Modern Law Review in 2025, employs a doctrinal and theoretical legal methodology to examine when political parties in the UK can be said to perform “public functions” and therefore be subject to judicial review. Trueblood analyses constitutional principles, case law under the Human Rights Act 1998, and recent decisions such as Tortoise Media v. Conservative Party (2023), where the courts rejected the idea that the Conservative Party’s internal selection of the Prime Minister could constitute a public function. Challenging this narrow approach, she argues that although political parties are generally private associations protected by freedom of speech and association, they sometimes operate as integral components of the governmental framework, thereby performing public roles that directly affect the functioning of representative democracy. Trueblood proposes a framework for identifying when party activities cross this threshold—particularly when they shape the composition or operation of government—and contends that such actions should, in principle, be amenable to judicial review. Her work advances a nuanced understanding of the constitutional status of political parties in the UK, bridging the gap between their private organizational character and their indispensable role in public governance.[21]

References

- ↑ https://www.adrindia.org/sites/default/files/Why%20political%20parties%20should%20be%20made%20public%20authorities.pdf

- ↑ https://eparlib.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/2495198/1/Rules_of_Procedures_E_2019_16th_edition.pdf

- ↑ https://www.sansad.in/getFile/bull2mk/2024/12-01-2024.pdf

- ↑ https://eparlib.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/2495198/1/Rules_of_Procedures_E_2019_16th_edition.pdf

- ↑ https://sansad.in/uploads/LSPP_Questions_Procedure_rules_2c7312313c.pdf

- ↑ https://sansad.in/uploads/LSPP_Questions_Procedure_rules_2c7312313c.pdf?

- ↑ https://cms.rajyasabha.nic.in/UploadedFiles/Procedure/RajyaSabhaAtWork/English/346-364/CHAPTER10.pdf

- ↑ https://mpa.gov.in/sites/default/files/English_Manual_06092019.pdf

- ↑ https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/1995/1/A1999-05.pdf

- ↑ 1995 SCC (5) 347

- ↑ AIR 2002 SC 2158

- ↑ (2002) 5 SCC 294

- ↑ https://www.pib.gov.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=196237

- ↑ Law Commission Report No 255

- ↑ Law Commission Report No 255

- ↑ Law Commission Report No 255

- ↑ https://apcz.umk.pl/CLR/article/view/CLR.2020.006

- ↑ https://www.kas.de/c/document_library/get_file?uuid=735c449b-fd52-c43f-6f58-403a818d3be9&groupId=252038

- ↑ Aradhya Sethia, Constitutional Particracy: Political Parties and the Indian Constitution, in The Cambridge Companion to the Constitution of India (Aparna Chandra, Gautam Bhatia, & Niraja Gopal Jayal, eds., Forthcoming 2024), available at SSRN: 4859875.

- ↑ Aradhya Sethia, Constitutional Particracy: Political Parties and the Indian Constitution, in The Cambridge Companion to the Constitution of India (Aparna Chandra, Gautam Bhatia, & Niraja Gopal Jayal, eds., Forthcoming 2024), available at SSRN: 4859875.

- ↑ Leah Trueblood, Public Functions of Political Parties in the United Kingdom, 88 Mod. L. Rev. (forthcoming 2025).