Presidential reference

What is Presidential Reference?

Through Presidential reference, the President may refer any question of law or fact of public importance to the Supreme Court for its opinion, based on the advice of the Union council of ministers. The Supreme Court may provide its opinion after such hearing as it thinks fit. However, the opinion is legally not binding on the President, and does not hold a precedential value for the courts to follow in subsequent cases. Article 143 as seen today has been influenced by Section 213 of the erstwhile Government of India Act, 1935. Section 213 empowered the Governor-General to seek the Federal Court’s opinion on significant legal issues. It was considered expedient to confer advisory jurisdiction upon the Federal Court, which led to the Constituent Assembly’s Union Constitution Committee accepting the idea of Presidential reference. It was included as Article 119 of the Draft Constitution of India, which formed the basis of Article 143.

Although it is not obligatory for the Supreme Court to render its opinion, out of the references made till date, the court has declined to provide its opinion for only one reference in 1993 with respect to the Ram Janmabhoomi case[1].

Further Article 317(1) of the Constitution provides that the President of India can only remove the Chairman or any other member of a Public Services Commission for misbehavior, but only after the Supreme Court, upon reference from the President, reports that the member should be removed, and after conducting an inquiry in accordance with Article 145.

Official definition of Presidential Reference

Article 143 of the Constitution confers advisory jurisdiction to the Supreme Court. It empowers the President of India to consult the Supreme Court if at any time, it appears to the President that a question of law or fact has arisen, or is likely to arise, which is of such a nature and of such public importance that it is expedient to obtain the opinion of the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court, after hearing as it thinks fit, may report its opinion to the President. Article 145 of the Constitution provides that any reference under Article 143 shall be heard by a bench of minimum five judges.

Article 317(1) provides the concept of Presidential reference in matters concerning the removal of the Chairman or any other member of a Public Service Commission from their office on the ground of misbehaviour. It provides that such member shall be removed by Presidential order, only after the Supreme Court, on reference being made to it by the President, has, on inquiry as prescribed by Article 145, reported that the member ought to be removed on any such ground.

Supreme Court Rules, 2013

Order XLII of the Supreme Court Rules provides the procedure for the consideration of a Special Reference under Article 143 by the Supreme Court. Order XLIII provides the procedure for Presidential references made under Article 317(1), or any statute.

As defined in case laws

There have been around fifteen references made since 1950 before the current reference. Many significant decisions have been rendered by the Supreme Court while adjudicating a case on reference.

- The first reference was made in the Delhi Laws Act case (1951), wherein the issue of the extent up to which the legislature could delegate its legislative function to the executive without violating the separation of powers doctrine arose. The Supreme Court laid down the contours of ‘delegated legislation’, through which the legislature could delegate legislative powers to the executive for effective implementation of any law.

- In Re Special Courts Bill, 1978[2], the Supreme Court elaborated on several general issues concerning its advisory jurisdiction under Article 143(1) of the Constitution, which is strictly confined to the Supreme Court and not the High Courts. The Court underscored the non-binding nature of advisory opinions, observing that such opinions do not have the force of law and are akin in value to the opinions of law officers. The Court remarked that “the question of the value of advisory opinions of the Supreme Court may have to be considered more fully on a future occasion”. The Court clarified Article 143(1) confers discretion upon the Court to refuse to answer a reference, indicating that responding to a Presidential reference is not obligatory, and the Court may decline if it deems fit. The Court held that it is not required to render opinions on speculative or hypothetical questions. The questions referred must involve substantial issues of constitutional or public importance, and should be specific rather than abstract inquiries.

Binding or Non-Binding nature

Although the Supreme Court generally held that advisory opinions under Article 143(1) are not binding (In Re Special Courts Bill and The Matter of Cauvery Water Disputes Tribunal, Re[3], there have been instances of reliance on advisory opinions. In Vasantlal Maganbhai Sanjanwala v. State of Bombay[4] A. I. R. 1961 S. C. 4 [S. C.], the Court relied on the advisory opinion in the Delhi Laws Act case. Similarly, in the Bearer Bonds case, Justice Bhagwati treated the Special Courts Bill opinion as binding, despite earlier acknowledgment that it was not. The conflict arises due to Article 141, which states that the “law declared” by the Supreme Court is binding. However, advisory opinions are given without opposing parties and are more consultative in nature. As there is no adjudication, they do not fall under “law declared” and thus do not attract Article 141. Therefore, although advisory opinions may be respected and followed, they are not binding precedents.

Official Database

Case category- Supreme Court website

- Presidential reference under Article 143 is given the category code 39.

- Reference under Article 317(1) for removal of Chairperson/member of Tribunal/Commission/ authority under any Central law where inquiry has to be conducted by the Supreme Court, is given the category code 40.

Case status- Supreme Court website

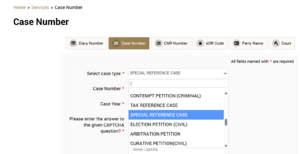

Presidential reference under Article 143 is classified as Special Reference for the purpose of case status on the Supreme Court website.

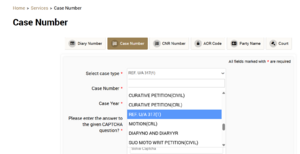

Further reference under Article 317(1) is classified as “ref. U/A Art.317(A)” as a case type for ascertaining case status.

International Experiences

The advisory jurisdiction of the Supreme Court of India, under Article 143(1) of the Constitution, finds parallels in several historical constitutional frameworks and in the committee documents produced during the drafting of the Indian Constitution. Despite this, the Constituent Assembly Debates and the reports of its sub-committees do not delve into the potential tensions or criticisms surrounding this power, either in Indian or foreign legal contexts. This suggests a general consensus among the framers that such a reference power was both desirable and necessary. However, the controversy around the recent Presidential references has reignited debates about the proper limits of the Supreme Court’s advisory jurisdiction. These disputes are similar to those seen in other common law jurisdictions, such as Australia, Canada, and the United States, regarding the relationship of the advisory jurisdiction of the Court and its adjudicatory role.

United Kingdom

The concept of advisory jurisdiction traces its origins to the United Kingdom, where, from the outset, the Crown would seek the opinion of judicial authorities before enacting any legislation. This consultative practice persisted even after the judiciary was formally institutionalized. The tradition of providing legal advice to the executive and the monarch remained unaffected. A significant development in this regard was the Judicial Committee Act of 1833, which, under Section 4, conferred the authority on the Privy Council, which was then the highest appellate body for courts outside the UK, to offer such advisory opinions.

United States of America

The U.S Constitution does not explicitly provide for or prohibit the issuance of advisory opinions. However, the U.S. Supreme Court has consistently rejected the idea of issuing such opinions, based on two core principles. First, the U.S. Constitution enshrines a strict separation of powers, and judicial involvement in non-adjudicative matters, such as advising the executive, would breach this doctrine. Second, the judiciary is empowered only to resolve actual disputes brought before it through proper legal channels. Consequently, advisory opinions are viewed as hypothetical and outside the scope of judicial power. This stance was first affirmed in Hayburn’s Case (1792), where the Court declined to offer advice, citing the separation of powers. The same principle guided its refusal in later cases such as Alabama State Federation of Labour v. McAdory, where the Court emphasized that it could only decide on existing legal controversies, not abstract or future-oriented issues. In Powell v. McCormack, the Court further clarified that it would not entertain political questions. While the federal judiciary maintains this position, some U.S. states allow their courts to issue declaratory judgments, which may function similarly to advisory opinions in practice.

Canada

Canada has embraced the concept of advisory jurisdiction, rooted in its British colonial legal heritage. The Supreme Court Act of 1875 formally recognized this power, which was preserved in subsequent re-enactments in 1906 and 1952. Under this framework, the Governor General can refer legal or factual questions to the Supreme Court, which is constitutionally obligated to answer them. Unlike India, where the Supreme Court may decline to answer a reference under Article 143, the Canadian Supreme Court does not enjoy such discretion. Moreover, advisory opinions issued by the Canadian Supreme Court are binding in nature, giving them the force of law. This differs significantly from India, where advisory opinions under Article 143(1) are considered persuasive but not binding. The power to issue advisory opinions in Canada is not limited to the Supreme Court; it extends to provincial courts as well, reflecting a more expansive and obligatory model of judicial advisory functions.

Research that engages with Presidential Reference

Presidential References and their Precedential Value: A Constitutional Analysis (National Law School of India Review)

The research article "Presidential References and their Precedential Value: A Constitutional Analysis"[5] by Deepaloke Chatterjee, examines the constitutional and jurisprudential status of advisory opinions issued by the Supreme Court of India under Article 143(1). The research establishes that such advisory opinions, although delivered by the highest court, do not possess binding precedential value. This is primarily because they are not the result of a lis (an actual dispute between parties) and do not involve the exercise of judicial power in the strict sense.

The paper further outlines arguments both supporting and opposing the idea that such opinions are binding, ultimately concluding that advisory opinions—despite being delivered by the apex court—do not constitute binding precedent. Instead, they should be viewed as persuasive authority, given their non-adjudicatory and consultative nature. This distinction, the author argues, is vital to maintaining the balance between the Court’s advisory and adjudicatory roles in a constitutional democracy.

Analysing Presidential References in India & Questions Which Follow (ILI Law Review)

The research article titled “Analysing Presidential References in India & Questions Which Follow” by Shivam Tripathi[6] offers a comprehensive examination of the Supreme Court of India's advisory jurisdiction under Article 143 of the Constitution. It traces the history and origin of this provision to the Government of India Act, 1935, and delineates the nature, scope, and limitations of presidential references. It establishes that the President's power to make a reference is broad and discretionary, allowing questions of legal or public importance to be placed before the Court. However, it recognizes the limited scope of advisory jurisdiction. The limitation is that it does not permit the Court to reopen or revisit its previous decisions and confines it to the specific questions referred. The article concludes that while advisory opinions do not hold the force of law, they play a vital role in guiding constitutional governance and reinforcing the dialogue between the judiciary and other branches of the state.

Challenges

- Overbroad Scope of Article 143: Article 143 does not limit the types of questions the President may refer to the Supreme Court. This opens the door for the Centre to encroach upon areas reserved for the States under the federal structure of the Constitution. For example, in In re Keshav Singh, the President referred questions related to state legislative privileges—an area under the State List—raising federalism concerns. Though no opinion was rendered, the Chief Justice noted that more restraint should have been exercised. A recommended practice is for the President to consult the concerned State before referring such matters, promoting cooperative federalism.

- Quasi-Legislative Role Due to Vague References: Under Article 143(1), vague or hypothetical questions referred by the President can push the Court into performing a legislative function. In re Special Courts Bill, the Court was asked to assess the constitutionality of a bill not yet enacted—thus reviewing legislation prematurely. Critics argue that such pre-enactment review departs from the Court’s judicial role and blurs institutional boundaries.

- Need for Judicial Discretion and Specificity: To maintain institutional balance, it is crucial that references under Article 143 be legally precise and not vague or speculative. Furthermore, the obligation under Article 143(2) should be revisited to restore judicial discretion, ensuring that the Supreme Court retains its autonomy and does not act as an advisory arm of the executive.

References

- ↑ Yubaraj Ghimire, Ashok Damodaran, “SC's rejection of presidential reference on Ayodhya temple issue upsets political parties”, Indian Express, July 17th 2013.

- ↑ In Re Special Courts Bill, [(1979) 1 SCC 380].

- ↑ The Matter of Cauvery Water Disputes Tribunal, Re, A.I.R. 1992 S. C. 522 [S. C.].

- ↑ Vasantlal Maganbhai Sanjanwala v. State of Bombay

- ↑ Deepaloke Chatterjee, "Presidential References and their Precedential Value: A Constitutional Analysis", the National Law School of India Review (Vol. 21, Issue 1), 2009. Accessible at: https://repository.nls.ac.in/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1052&context=nlsir

- ↑ Shivam Tripathii; ANALYSING PRESIDENTIAL REFERENCES IN INDIA & QUESTIONS WHICH FOLLOW ILI Law Review -2020 (Winter Issue) e-ISSN-0976-1489 available at; https://ili.ac.in/ilrwin20.html