Public Authority

Who is a Public Authority?

Section 2(h) of the Right to Information Act, 2005 defines a ''Public authority'' as "any authority or body or institution of self government established or constituted by or under the Constitution, or by any other law made by the Parliament or a State Legislature; or by notification issued or order made by the Central Government or a State Government." Governmental and Non-Governmental bodies which are owned, controlled or substantially financed by the Central Government, or State Government also fall within the definition of public authority.

The purpose behind including such a wide range of bodies under the definition was to ensure that any institution performing a public function or handling public funds remains open to public scrutiny. The RTI Act was enacted to make governance more transparent, and defining what qualifies as a public authority forms the very foundation of this transparency mechanism.[1]

The RTI ACT 2005, empowers citizens with the right to access information under the control of public authorities. Accordingly, the RTI Act creates a legal Framework to make this right by defining public authorities, enabling citizens to seek information from them. It also imposes penalties on officials of public authorities for failing to disclose the information as defined in Section 2(f). The Central Information Comission (CIC) and courts have repeatedly clarified that the nature of funding and the performance of public functions are key criteria in determining whether an organisation qualifies as a public authority.[2]

Meaning of public authority in case laws

Indian courts have played a vital role in clarifying what entities fall under the term public authority. In Shivanna Naik V. Bangalore University[3], Karnataka university was deemed to be a public authority under Article 12 of the Constitution. Other cases have held co-operative societies as public authorities only in instances where the society is substantially financed directly or indirectly by the State Government.

An institution run by the registered society and providing education to the society, which owns a permanent building and receives grants-in-aid from the state falls under the definition of the "Public authority." Additionally, in Bihar Public Commission V. State Of Bihar, the Bihar public service commission was held to be a public authority.[4][5]

The judiciary has also clarified that cooperative societies or other semi-private entities can be considered public authorities only when they are substantially financed by the government or perform significant public functions. For example, educational institutions receicing regular government grants and serving a public purpose have been recognized as public authorities under the Act. [6]

Comparetively, international frameworks such as the UK Freedom of Information Act 2000 and the UN Convention against Corruption (2003) adopt a similarly broad understanding. These laws emphasize that ay institution involved in public administration, public service delivery, or the use of public funds must remain accountable and transparent. This reflects a global trends towards openness in goverance.[7]

In India, the Central Information Commission (CIC) regularly issues directions to ensure that ministries and departments register all qualifying bodies as public authorities. When there is ambiguity, the CIC has the power to order registration under its monitoring software. This proactive approach prevents departments from bypassing RTI obligations by failing to designate themselves or their subsidiaries as public authorities.

List of Public authorities

Under the Right to Information (RTI) Act, 2005, public authorities include:

- Central Government Ministries and Departments.

- State Government Departments.

- Public Sector Undertakings (PSUs).

- Autonomous Bodies (e.g., universities, councils).

- Local Authorities (e.g., municipalities, panchayats).

- Judicial and quasi-judicial bodies.

- Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) that receive substantial funding from the government.

The term "substantial" has been interpreted broadly, not limited to a numerical threshold but based on whether the funding enables or influences the functioning of the institution. This interpretation was supported by the Central Information Commission in several decisions, notably the Indian Olympic Association case, which clarified that financial dependence on the government can bring an organization within the ambit of a public authority.

This wide inclusion ensures that citizens can access information about how public money is utilized, even when it is channeled through semi- governmental or non governmental bodies. For example, educational trusts and cooperative societies receving continuous state aid or performing government-delegated tasks have been recognized as public authorities under the Act.

Every public authority is required to appoint a Public Information Officer (PIO) to handle RTI requests.

REGISTRATION OF PUBLIC AUTHORITY

All entities likely to be qualified as a PA must be registered with the Central Information Commission by the concerned ministries/ departments. Wherever an entity are due to be registered as PAs, and any information/complain of this nature is received, the CIC may direct the concerned ministry / department to register such entities as a PA in CIC software.

The CIC takes a proactive role and directs all concern ministries / departments to follow to uniform pattern while registering such type of PAs. However, the right for inclusion, merger, bifurcation and deletion of any PA vests with the controlling ministries/ departments. These directions aim to avoid duplication, omissions, or inconsistencies between the records maintained by the central and state governments. For instance, when a department is reorganized or merged, the registration details must also be updated to reflect such administrative changes.

Registration is not merely procedural-it plays a critical role in ensuring that the public can easily identify which institutions are accountable under the RTI framework. Once registered, each public authority is expected to appoint designated officials, such as Public Information Officers(PIOs) and First Appellate Authorities (FAAs), who facilitate information requests and handle appeals.

The Department of Personnel and Training (DoPT), which is the nodal agency for implementing the RTI Act, regularly updates its RTI Online portal to include the names and contact details of registered public authorities. Citizens can access this portal to file RTI requests electronically and track them across various ministries and departments.

By ensuring that all public authorities—central, state, and local—are properly registered and accessible through a centralized database, the system strengthens the accountability mechanism envisioned by the RTI Act. It also ensures that smaller and semi-autonomous bodies do not evade public scrutiny simply because of administrative oversight or definitional ambiguity.

Obligations of Public Authorities:

As defined in the RTI ACT 2005, Section 4(1) contains a list of the following obligations of public authorities:

1. Maintenance of records: Every public authority is required to maintain all its records duly cataloged and indexed. In order to facilitate access to its records, the public authority shall ensure that all the records that are appropriate for computerisation are computerized and connected through a network across the country on various systems, within a reasonable time frame and according to resource availability.

This provision addresses one of the major challenges faced before the enactment of the RTI Act— the inaccessibility of government records due to poor documentation, loss, or bureaucratic opacity. The National Archives of India, under the Public Records Act, 1993, also plays a supporting role in ensuring proper record management, which directly contributes to efficient RTI implementation.[8]

Many departments have now transitioned to digital recordkeeping systems. The e-Office initiative of the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology, for example, has greatly simplified file management by replacing paper-based systems with electronic workflows. This not only ensures faster access to information but also builds institutional memory that is searchable and less prone to manipulation.

2. Publication of certain matters: Every public authority is required to publish the following particulars within 120 days of the enactment of the Act. These include:

- Particulars of its organisations, functions, and duties;

- Powers and duties of its officers and employees;

- Procedure followed in the decision-making process, including channels of supervision and accountability;

- Employee directory of such public authority

- Monthly salary given to employees and officers

- Details of budget allocated to its agencies

- Details regarding information held in electronic form

- Particulars of facilities available to citizens for obtaining information

- Names and designations of the Public Information Officers etc.

- Every public authority shall provide reasons for its judicial or administrative decisions to those affected by it.[9]

Primary Role of Public Authority:

Under the Right to Information (RTI) Act, public authorities form the backbone of India's transparency framework. Their primary responsibility is to enable citizens to acess information that ensures accountability and good governance. The RTI Act transforms government offices from being gatekeepers of information to facilitators of transparency.

In practice, this means that every public authority—whether a ministry, department, public sector enterprise, or local body—has both proactive and reactive duties: to provide information when requested and to make crucial dara available to the public even before it is sought.

1. Providing Information:

Authorities are expected to respond to RTI requests within a stipulated time frame (typically 30 days) under section 7(1) of the Act.If the information concerns the life or liberty of a person, it must be furnished within 48 hours. This legal obligation ensures timely access and reduces bureaucratic delay. When a request is made to the wrong department, the Public Information Officer (PIO) must transfer it to the appropriate authority within five days under section 6(3). They are mandated to provide complete and accurate information, apart from assisting applicants by directing the query to the appropriate authority. This reflects the citizen-centric ethos of the Act, ensuring that procedural barriers do not obstruct the right to information.

The Central Information Comission (CIC) and various High Courts have repeatedly emphasized that incomplete or evasive responses violate bot the letter and spirit of the Act. Transparency is not optional—it is a statutory duty.[10]

2. Designating Public Information Officers

Section 5(1) of the RTI ACT requires a public authority to designate "as many" officers as central public information officer or the state public information ,as the case may be, in all administrative units and offices it may be necessary to provide information to persons requesting for the same. They were to be designated within 100 days of enactment of the act. https://wblc.gov.in/sites/default/files/Role%20of%20PIO.pdf

These officers serve as the key interface between citizens and the government, ensuring that information requests are received, processed, and delivered efficiently.

They must also assist applicants who are unable to make written requests and guide them in accessing the relevant records. Where the information sought concerns another department, the PIO must transfer it promptly to ensure that citizens are not bounced between offices.

The West Bengal Labour Commission's Official guidelines underline that PIOs carry a dual responsibility—both as information providers and as facilitators of transparency— ensuring that citizens can meaningfully exercise their right to know. [11]

Failure to appoint or empower PIOs can lead to administrative penalties under Section 20 of the RTI Act, including monetary fines imposed by the Information Commission.

3. Maintaining Records

Public Authorities must maintain accurate and updated date records of information. They must also ensure that such records must be accessible when sought.Section 4(1)(a) of the RTI Act directs every authority to “maintain all its records duly catalogued and indexed in a manner and the form which facilitates the right to information.” This obligation ensures that when citizens seek information, it can be readily located and provided without delay or confusion.

Many departments have now adopted digital record management systems, aligning with the e-Office initiative of the Government of India. Digitization has significantly reduced paperwork, improved accountability, and minimized the loss or misplacement of files—a common problem in earlier decades.

The National Archives of India, under the Public Records Act, 1993 also provides framework to ensure the long term preservation and accessibility of public records, supporting RTI implementation through better data governance.

4. Ensuring Transparency: Under Section 4(1)(b) of the Act, public authorities are required to voluntarily publish information about their organizational structure, powers, functions, decisions-making procedures, and budgets. This is known as "suo motu disclosure."

The idea is that citizens should not always have the file RTI applications—key information should already be available online or on public notice boards.

The Department of Personnel and Training (DoPT), through its 2013 Office Memorandum,reiterates that every ministry and department must regularly update these disclosures. The memorandum also directs that information be presented in user-friendly formats and made accessible to persons with disabilities.

This proactive approach reduces administrative burden, builds trust, and empowers citizens to engage more meaningfully with public institutions.

5. Maintaining Confidentiality: While transparency is the cornerstone of the RTI Act, the law also recognizes that some information must remain confidential to safeguard national interest, personal privacy, and security.

Section 8(1) of the Act lists specific exemptions—such as information that may affect national security, trade secrets, or ongoing investigations. However, even these exemptions are not absolute. The public interest override in Section 8(2) allows disclosure when the larger public interest outweighs potential harm.

Thus, the role of public authorities is twofold: to uphold openness where possible and to exercise discretion responsibly when confidentiality is justified.

The Supreme Court of India, in Girish Ramchandra Deshpande v. CIC, clarified that disclosure of personal information may be refused unless a demonstrable public interest exists.This balance between transparency and privacy is what keeps the RTI framework credible and constitutionally sound.[12]

SUO MOTU DISCLOSURE

1. Every public authority must provide as much information Suo motu to the public via various reasonable means of communication. This is to ensure that citizens need to minimally resort to the use of the Act to obtain information. The Internet being one of the most effective means of communications, the information may be posted on the website.

2. Section 4(1)(b) of the Act, in particular, requires every public authority to publish following sixteen categories of information:

- (a)the parliament of its organization, functions and duties;

- (b)the powers and duties of its officers and employees;

- (c)the procedure followed in the decision making process, including channels of supervision and accountability;

- (d)the norms set by it for the discharge of its functions;

- (e)the rules, regulations, instructions, manuals and records, held by it or under its control or used by its employees for discharging its functions;

- (f)a statement of the categories of document that are held by it or under its control;

- the particulars of any arrangement that exists for consultation with, or representation by, the members of the public in relation to the formulation of its policy or implementation thereof;

- (g)a statement of the boards, councils, committees and other bodies consisting of two more persons constituted as part or for the purpose of its advice, and as to whether meetings of those boards, councils, committees and other bodies are open to the public, or the minutes of such meetings are accessible for public;

- (h)directory of its officers and employees;

- (i)the monthly remuneration received by each of its officers and employees, including the system of compensation as provided in its regulations;

- (j)the budget allocated to each of its agency, indicating the particulars of all plans, proposes expenditures and reports on disbursements made;

- (k)the manner of execution of subsidy programmes, including the amounts allocated and the details of beneficiaries of such programmes;

- (l)particulars of recipients of concessions, permits or authorizations granted by it;

- (m)details in respect of the information, available to or held by it, reduced in an electronic from;

- (n)the particulars of facilities available to citizens for obtaining information, including the working hours of a library or reading room, if reduced in an electronic from;

- (o)the names, designations and other particulars of the Public Information Officers;

3. Besides the above categories of information, the Government may prescribe other categories of information to be published by any public authority. It is to be noted that publication of the information as referred to above is not optional, but rather a statutory requirement which every public authority is bound to meet under Section 4(1)(b).

4. The public authority is obliged to update the aforementioned categories of information annually. It is advisable that, as far as possible, the information should be updated periodically as and when new developments occur. Particularly, in case of online publication, the information should be maintained and updated timely.[13]

The purpose is to minimize the need for individual citizens to request information repeatedly. If information is already available online or in the public domain, the need for formal RTI applications naturally declines, leading to faster access and reduced administrative burden.

The Department of Personnel and Training (DoPT) periodically issues guidelines reinforcing these requirements, reminding departments to update their proactive disclosure sections regularly.[14] According to the DoPT Office Memorandum No. 1/6/2011-IR dated 15 April 2013, every public authority should ensure that suo motu disclosures are comprehensive, up-to-date, and easily navigable for citizens.[15]

A key innovation has been the introduction of the “RTI Dashboard” — an online repository that tracks the status of proactive disclosures and compliance levels across ministries. This helps in identifying departments that lag behind and provides a transparent view of how well each institution fulfills its obligations.

Designation of Public Information Officers

The Right to Information Act, 2005 accords a central role to Public Information Officers (PIOs), recognizing them as the statutory interface between public authorities and citizens. The appointment of PIOs ensures that the right to information, as guaranteed under the Act, is effectively operationalized across all tiers of government. Every public authority, whether at the Central, State, or local level, is mandated to designate one or more officers to discharge the functions of providing information to applicants under Section 5 of the Act. The presence of PIOs institutionalizes the process of information dissemination, thereby promoting transparency, accountability, and participatory governance within the framework of administrative law.

Section 5(1) requires public authorities to appoint Central Public Information Officers (CPIOs) and State Public Information Officers (SPIOs) within 100 days of the Act’s commencement. Such officers are required by the Act to furnish the requested information.

Section 5(2) establishes a Central Assistant Public Information Officer or a State Assistant Public Information Officer at each sub-divisional or other sub-district levels. Such officials shall accept applications for information or appeals under the Act and send them to the CPIO/SPIO or the senior officer indicated in Section 19(1), the Central Information Commission, or the State Information Commission, as applicable.

This system ensures that citizens can file RTI applications even in rural or remote areas without needing to approach higher offices directly.

Responsibilities and functions of Public information officers

Section 5(3) of the RTI Act, 2005 assigns CPIOs and SPIOs the following responsibilities:

- Respond to information requests from any citizen within the prescribed time limits — generally 30 days, or 48 hours if the information concerns the life or liberty of a person. Failure to meet these timelines can attract penalties under Section 20 of the Act.

- Provide assistance to applicants, especially those who are illiterate, disabled, or unable to make a written request. If an application is made to the wrong office, the PIO must transfer it to the correct authority within five days as per Section 6(3).

- Maintain proper records and indexes to ensure that requested information can be located quickly. This responsibility aligns with the record-maintenance obligations under Section 4(1)(a) of the Act.

- Facilitate transparency by proactively disclosing commonly requested information, thereby reducing the number of formal RTI applications.

- Balance openness and confidentiality, applying the exemptions listed under Section 8(1) judiciously and ensuring that no information is withheld without valid justification.

In practical terms, PIOs serve as both facilitators and guardians of the citizen’s right to know. They must handle requests professionally, maintain neutrality, and avoid unnecessary denials of information.

Penalties

The CIC/SIC has the authority to impose sanctions on the CPIO/SPIO for purposeful violations of the Act when resolving a complaint or an appeal under the Act. Before any decision regarding the application of a penalty is made, the CPIO/SPIO in question must be given a reasonable opportunity to be heard. The burden of proving that he behaved reasonably and diligently rests solely on the concerned CPIO/SPIO.

A penalty is imposed at the rate of Rs. 250 per day till the application is received or information is furnished. However, the total amount of the penalty shall not exceed Rs. 25,000. Section 20(1) of the Act lists several grounds for which penalties maybe imposed:

- unreasonable refusal to receive an application for information

- information not provided within the time period specified in Section 7(1)

- mala fide rejecting of the information request

- knowingly provided false, incomplete, or misleading information

- the applicant’s requested information was destroyed

- obstruction in any way in providing the information

In practice, the Information Commissions have exercised their powers with caution, ensuring penalties are imposed only where clear malafide intent or gross negligence is shown.[16] In R K Jain v Ministry of Finance, the CIC held that mere delay without evidence of bad faith is not penal.[17] Conversely, in CIC v State Bank of India, the Commission imposed a penalty when the PIO deliberately withheld information despite repeated directions.[18]

State Commissions have followed this standard. The Maharashtra SIC, in Ramesh Chavan v Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai (2015), imposed the statutory maximum penalty of ₹25,000 where records were intentionally destroyed.[19] The Tamil Nadu SIC has further clarified that penalties function as a “remedial and corrective mechanism” aimed at compliance, not punishment.[20]

These decisions underscore that the penalty mechanism operates under judicial prudence and fairness, ensuring that transparency does not compromise administrative due process.[21]

Role of First Appellate Authority (FAA)

It is the responsibility of PIO of a public authority to supply correct and complete information within the specified time to any person seeking information under RTI act 2005. The failure to do so, on certain counts, allows citizens to appeal to the First Appellate Authority. The act contains provision to appeal to tide over such a situation. The 1st appeal is heard within public authority by an officer designated as the First Appellate Authority by the concerned public authority.

The First Appellate Authority (FAA) plays a crucial role in maintaining transparency and accountability within the information delivery process. Acting as the first internal review mechanism, the FAA ensures that applicants are not denied their right to information due to administrative lapses, delays, or arbitrary decisions of Public Information Officers (PIOs). Under Section 19(1) of the Right to Information Act 2005, an appeal may be filed within 30 days from the date of expiry of the prescribed period or from the receipt of the PIO’s decision, though the FAA may admit an appeal after this period if sufficient cause for delay is shown.[22]

The FAA is mandated to dispose of the appeal within 45 days of its receipt, providing a reasoned and written order to the applicant in accordance with Section 19(6) of the Act.[23] In doing so, the FAA must consider whether the PIO acted in good faith and in compliance with the provisions of the RTI framework. Importantly, the FAA exercises quasi-judicial authority, enabling it to direct disclosure, recommend corrective steps, and, where necessary, propose disciplinary action against erring officials.

Judicial and administrative interpretations have emphasized the independence and proactive function of the FAA. In R.K. Jain v Ministry of Finance, the Central Information Commission observed that FAAs should not merely endorse PIO decisions but must issue reasoned, independent findings based on facts and law.[24] Similarly, the Department of Personnel and Training (DoPT), in its Guide on the Right to Information Act 2005 (2022), clarifies that FAAs serve as impartial arbiters within public authorities, ensuring that administrative discretion does not undermine the citizen’s right to know.[25]

By serving as a vital link between information seekers and Information Commissions, the FAA reinforces institutional accountability and strengthens the overall architecture of transparency envisioned by the RTI Act.[26]

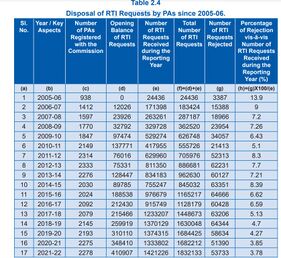

Statistical Overview of Public Authorities

Annual report of Central Information Commission ( 2022-2023)

1.Ministry wise list of authority who have have not submitted annual return. Retrieved from pg 251. https://cic.gov.in/sites/default/files/Reports/AR2021-22E.pdf

Annual report of CIC (2022-2023)

STATE WISE ANNUAL REPORT (2022-2023);

HARYANA- The Haryana State Information Commission in its Annual Report 2022–2023 highlighted its consistent efforts to strengthen the implementation of the Right to Information Act across departments. The report showcases a steady rate of disposal of second appeals and complaints, indicating improved efficiency in processing RTI matters. The Commission also emphasized training and awareness initiatives for Public Information Officers (PIOs) to ensure greater compliance with the statutory timelines under Section 7(1) of the Act. Furthermore, the report noted that penalties were imposed in cases of deliberate delays or refusals to furnish information, thereby reinforcing accountability within the administrative machinery (Haryana State Information Commission, 2023).https://cicharyana.gov.in/

UTTAR PRADESH - The Uttar Pradesh Information Commission’s Annual Report 2022–2023 reflects substantial progress in promoting transparency and reducing pendency in appeals. The Commission recorded a significant number of cases disposed of during the reporting year, while continuing to address challenges related to delays and incomplete responses by PIOs. It also stressed the importance of proactive disclosure by departments to minimize the need for individual RTI applications. Regular capacity-building programs were organized to enhance the understanding of information officers regarding their duties and the scope of exemptions under the Act (Uttar Pradesh Information Commission, 2023).https://upic.gov.in/

PUNJAB -According to the Punjab Information Commission’s Annual Report 2022–2023, the state demonstrated notable progress in ensuring compliance with the RTI framework. The Commission focused on expeditious disposal of second appeals and complaints and continued to monitor adherence to orders passed under Section 19(8) of the Act. The report also highlighted that the Commission remained proactive in imposing penalties under Section 20(1) for non-compliance and delays, thereby maintaining the integrity of the information regime. Training sessions and outreach activities were held to sensitize public authorities about their obligations (Punjab Information Commission, 2023).https://infocommpunjab.com

UTTARAKHAND

The Uttarakhand Information Commission’s Annual Report 2022–2023 underscored its commitment to transparency and citizen empowerment through timely resolution of RTI appeals. The report recorded a steady decline in pending cases compared to previous years, reflecting improved administrative responsiveness. It also identified recurring issues, such as inadequate record management and partial information disclosure by some departments. To address these challenges, the Commission proposed the adoption of digital record-keeping and more rigorous training for PIOs to ensure uniform compliance with the RTI framework (Uttarakhand Information Commission, 2023).https://uic.uk.gov.in/index/index.php

Rajasthan-The Rajasthan Information Commission in its Annual Report 2022–2023 reported progress in ensuring that public authorities adhere to the mandates of the RTI Act. The Commission’s analysis showed a consistent rate of appeal disposal and increased imposition of penalties for willful non-compliance. It also stressed the importance of public awareness programs and transparency workshops to strengthen citizen participation in governance. The report called for improved coordination between departments to facilitate the timely sharing of information and reduce procedural bottlenecks (Rajasthan Information Commission, 2023).https://ric.rajasthan.gov.in/

References

- ↑ PK Das, Handbook on the Right to Information Act 2005 (Universal Law Publishing 2005).

- ↑ Department of Personnel and Training (n 2).

- ↑ 2006 (1) AIR KAR R 130

- ↑ AIRONLINE 2009 SC 343

- ↑ Das PK, Handbook on the Right to Information Act, 2005 (Universal Law Publishing Co 2005)

- ↑ Government of Tripura, Guidelines for Public Authorities (retrieved from https://rti.tripura.gov.in/guidlines-for-the-public-authorities).

- ↑ Freedom of Information Act 2000 (UK); United Nations Convention against Corruption (adopted 31 October 2003, entered into force 14 December 2005) 2349 UNTS 41.

- ↑ The Public Records Act 1993, and National Archives of India guidelines.

- ↑ https://blog.ipleaders.in/right-to-information-act-2005-a-comprehensive-overview/#Obligations_of_public_authorities_Section_4

- ↑ Central Information Commission, Handbook for Public Information Officers (2020).

- ↑ West Bengal Labour Commission, Role of PIOs under RTI Act (official circular), available at https://wblc.gov.in/sites/default/files/Role%20of%20PIO.pdf

- ↑ Girish Ramchandra Deshpande v. CIC (2013) 1 SCC 212.

- ↑ Guidelines for Public Authorities, Govt. of Tripura. Retrived from https://rti.tripura.gov.in/guidlines-for-the-public-authorities

- ↑ Department of Personnel and Training, Guidelines for Suo Motu Disclosure under Section 4 of the RTI Act (2013).

- ↑ DoPT Office Memorandum No. 1/6/2011-IR, dated 15 April 2013.

- ↑ Central Information Commission – Annual Report 2022-23 https://cic.gov.in/.

- ↑ R K Jain v Ministry of Finance (CIC/AT/A/2007/01029, 16 June 2009).

- ↑ CIC v State Bank of India (CIC/SM/A/2011/001056).

- ↑ Ramesh Chavan v Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai (Maharashtra SIC, 2015).

- ↑ Tamil Nadu State Information Commission Decisions (2020) https://www.tnsic.gov.in/.

- ↑ Central Information Commission v PIO Ministry of Environment and Forests (CIC/SG/A/2011/002545, 2012).

- ↑ Right to Information Act 2005, s 19(1).

- ↑ Right to Information Act 2005, s 19(6).

- ↑ R.K. Jain v Ministry of Finance CIC/AT/A/2007/01029 (16 June 2009) (Central Information Commission).

- ↑ Department of Personnel and Training (DoPT), Guide on the Right to Information Act, 2005 (DoPT 2022) https://rti.gov.in/.

- ↑ Central Information Commission, RTI Manual (CIC 2023) https://cic.gov.in/.