Public interest litigation

What is Public Interest Litigation (PIL)?

Public Interest Litigation (PIL) is filed in a court of law for protection of public interest. It is a concept derived from American jurisprudence. It has been designed to provide representation to those groups or sections that were previously unrepresented. It can be filed by any member of the public to redress issues that affect the public at large, such as environmental issues, terrorism, as well as those involving violation of constitutional rights. In the Indian context, the scope of issues deemed to fall within the realm of “public interest” continues to evolve over time.

Official Definition of Public Interest Litigation

The term “Public Interest Litigation” has not been defined in any statute. It emerged as a concept through a series of cases over time. The seeds of PIL litigation were sown by Justice Krishna Iyer, in 1976, in the case of Mumbai Kamgar Sabha v. Abdulbhai Faizullabhai[1]. Generally, to bring a suit or appear before the Court the principle of locus standi must be adhered to. This principle provides that the person bringing the action must have the capacity and grounds to do so. The party bringing such action must have a direct and personal stake in the outcome of the case. Justice Krishna Iyer, in the above case, identified that public interest can be promoted by a spacious construction of this concept of locus standi in order to allow people to invoke the jurisdiction of higher courts where the remedy is shared by a considerable number, particularly when they are weaker. Article 226 is viewed through a wide perspective, it can be used to redress collective or common grievances, as distinguished from assertion of individual rights, which has been the focus of the traditional view. This paved the way for the concept of PIL, as it enabled citizens to fight for issues, to which they may bear a personal connection. PIL began to be used as a means of representation of poorer or underprivileged sections of the society.

Justice Bhagwati also made significant contributions towards the conceptualization of PIL in India. The first PIL filed by Kapila Hingorani in 1979 to secure the release of almost 40000 under-trials from Patna’s jails in the case of Hussainara Khatoon v. State of Bihar[2]. The Bench led by Justice Bhagwati not only proceeded to make the right to a speedy trial the main issue in the case, but it also issued an order for the general release of nearly 40,000 people. In doing so, the Court strengthened the concept of PIL.

Statutory Provisions

The Supreme Court's jurisdiction under Article 32 of the Indian Constitution and the High Court’s jurisdiction under Article 226 can be invoked for entertaining a PIL, and therefore a wide range of remedies can be awarded for matters litigated in public interest. Courts have the power to treat a letter addressed to it as a writ petition, if addressed by the aggrieved person or any public-spirited individual or a social action group for the enforcement of legal or constitutional rights to any person who, upon poverty or disability, are not able to approach the court for redress. There exists a PIL cell which screens all letter-petitions before placing them before the Court, based on guidelines of the Supreme Court.

The idea of PIL can be found in Article 39A of the Indian Constitution, which provides a goal to ensure equal justice and provide legal assistance. PIL litigation supports this goal by empowering courts to deal with matters that are concerning to the public at large, and by providing a means of representation to the weaker sections of the society.

Order 38 Rule 12 of the Supreme Court Rules, 2013[3] deals with PILs. It provides the procedure and details involved in filing a PIL. It also provides the various ways in which a PIL can be instituted. Further, to deal with the misuse of PILs, it provides that the Court may impose exemplary costs on the petitioner if it finds the petition to be frivolous or instituted with oblique or mala fide motive or lacks bona fides.

Alternate Remedies

Statutory relief- Where a statute creates a right or a liability, and at the same time also prescribes the remedy or procedure for the enforcement of such right or liability, then the relief provided under the statute may be resorted to, before invoking Court’s jurisdiction under Article 32 or Article 226. This may include approaching the various Tribunals constituted for different subject-matters.

Civil suits- If the issue involves violation of rights without broader public interest implications, civil suits can be filed in the appropriate civil court.

Criminal complaints- In criminal matters, complaints can be with the police or with the Magistrate, as per provisions under the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023 (formerly the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973).

Misuse of PILs

Originally, PILs were intended to allow marginalized individuals and groups access to the higher courts through proceedings brought by unaffected parties. However, in recent times it has become an extension of political theatre. There has been an increasing influence of optics on filing of PILs. Consequently, filing of many frivolous petitions under the guise of PILs can be observed in recent years. The basis of the concept of PIL is the relaxation of the principle of locus standi. However, this has led to the misuse of PILs. PILs are filed even when there is no involvement of public interest, for extraneous and ulterior motives. As PIL is a less expensive tool than private litigation, it can be misused to settle personal vendettas. PILs are registered in pursuance of political or business interests, rather than public interests. Many PILs are filed in the Supreme Court without showing that there has been a violation of fundamental rights. There also lies the aspect of publicity, which causes petitioners and courts to cherry-pick issues that will garner more public attention, rather than serve public interest.

Types of PILs

PILs can be broadly divided into 2 categories:

- Representative Social Action- In this form of PIL, a member of the public can seek judicial redressal as a representative of either a person or such class of persons, who are unable to approach the Court due to socially or economically disadvantaged position in society. The petitioner is accorded locus standi as representative of such other person or group of persons. The case of Hussainara Khatoon demonstrates representative form of PIL.

- Citizen Social Action- This form of PIL empowers anyone with a sufficient interest to assert a right. The petitioner is accorded locus standi to sue as a member of the public, to whom public duty was owed. This form of PIL was first recognized in the S P Gupta v. Union of India[4], which dealt with the transfer of judges. In this case, the Court entertained the PIL based on the contention that public interest existed assuring the freedom of the judiciary from political influence.

Difference in Nomenclature across High Courts:

PILs have variations in their nomenclature, according to the State, and hence vary across High Courts. Some High Courts consider PILs under the category of writ petition.

The following High Courts have a separate designation for PILs: Chhattisgarh, Bombay, Allahabad, Karnataka, Calcutta, Gujarat, Rajasthan, Gauhati, Andhra Pradesh, Jammu and Kashmir, Telangana, Manipur, Meghalaya, Uttarakhand, Tripura.

Official Documents

Supreme Court Guidelines[5]

The guidelines issued by the Supreme Court lays down instances of entertaining a PIL involving individual/ personal matters. It lays down conditions for considering letter petitions as PILs. PILs are first reviewed by the PIL Cell. Only cases falling under the categories specified under the guidelines are placed before a Judge nominated by the Chief Justice of India (CJI). Registrars ensure adherence to guidelines before cases are processed further. The framework seeks to ensure that PILs serve their intended purpose of addressing public interest issues by filtering out personal grievances and matters better suited for other judicial or administrative forums.

High Court Guidelines

- The High Court of Karnataka (Public Interest Litigation) Rules, 2018[6] provides for constitution of PIL Cell, which is entrusted with the duty of screening letter petitions before placing it before the PIL Committee. The guidelines lay down the categories of those letter petitions that can be considered as PILs. Once approved by the PIL Committee, the PIL is place before the Chief Justice. The framework provides for appointment of suitable advocates as amicus curie to assist the Court for effective disposal. Further, the modes of entertaining a PIL are provided. Detailed instructions for filing PIL is provided, along with the details to be furnished by the petitioner.

- The Punjab and Haryana High Court follows the Maintainability of Public Interest Litigation Rules, 2010[7]. These rules lay down the categories of subject-matter for maintaining a PIL. There is also a specific provision that enlists the instances in which Public Interest Petitions received through post can be entertained. This includes petitions sent by prisoners or detenus.

- Himachal Pradesh High Court Public Interest Litigation Rules, 2010[8] were framed with a view of preserving the purity and sanctity of PIL. It sought to keep a check on frivolous letters or petitions. Along with the categories of subject- matter that can be considered as PILs, the framework also specifies the factors to be considered before entertaining a PIL. Communications to be treated as PILs can be in the form of letters, petitions, complaints or newspaper clippings.

- Orissa High Court Public Interest Litigation Rules, 2010[9] provides the format for filing a public interest petition, and the rules pertaining to the same. It requires Court to prima facie verify the credentials of the petitioner/petitioners, correctness of the contents of the petition and that substantial public interest is involved in the PIL, before entertaining it. It provides for exemplary costs if a petition is found to be frivolous, or due to extraneous or ulterior motive.

- Delhi High Court (Public Interest Litigation) Rules, 2010[10] provides for a PIL Cell, which is to process all letter petitions for being placed before the PIL Committee. The framework also provides for the constitution of PIL Bench to hear all matters of PIL. The categories of letter petitions to be entertained as PILs are laid down. The instructions to file such PILs are also defined in the rules.

PIL Cell

PIL Cells are bodies constituted under the PIL Guidelines of the Supreme Court and the respective High Courts of each state. The Cells are entrusted with the duty to process and screen letter petitions to ascertain whether they can be entertained as PILs. In the Supreme Court, following screening by the PIL Cell, the petition will be placed before a Judge to be nominated by Hon'ble the Chief Justice of India for directions, after which the case will be listed before the Bench concerned.

In High Courts, PIL Cells are constituted by the Chief Justice of the respective states. Following screening by the PIL Cell, the petition is placed before the PIL Committee for approval. PIL Cells are also responsible for preparing a summary in English of the petition and the points of public concern, if a petition is found to be eligible as a PIL. On approval of the Committee, it is placed before either the Chief Justice of the concerned High Court or division bench, according to the rules of the concerned state.

Maintainability of PILs

The Court can entertain PILs if it is convinced that constitutional rights of a vulnerable group of individuals have been modified or public interest at large has been affected. A PIL by any member of the public or social action group acting bonafide can invoke the writ jurisdiction of the High Courts, under article 226 or that of the Supreme Court, under Article 32, seeking redressal against violation of legal or constitutional rights of persons who due to social or economic or any other disability cannot approach the Court, can be entertained by the Court.

The Court needs to be convinced that the person filing PIL has sufficient interest and is acting in good faith. In certain cases, the Court can deny entertaining a PIL on the grounds of existence of an alternate remedy. However, it is not an absolute bar on maintainability of PIL.

International Experience

The United States (US)

PIL is commonly known as public interest law in the US. The concept of PIL litigation, as observed in India today, was adopted from American jurisprudence. The idea originated in the 1960s, when the US witnessed a phase of unrest. PIL evolved during this time. This branch is referred to as public interest law. It was built by the practice of lawyers and public spirited individuals who sought to precipitate social change through court-ordered decrees that reform legal rules, enforce existing laws, and articulate public norms. It includes all efforts made to provide legal representation to unrepresented groups and interests. The idea of legal aid laid down the foundation for the evolution of PIL. The concept has undergone changes over the years in their common law based system.

The United Kingdom (UK)

The genesis of PIL in the UK lies mainly in the common law dimension of judicial review. PIL in the UK refers to liberal access to courts for pressure groups, representative bodies and statutory organizations that wish either to bring proceedings in their own names or to intervene as third parties in ongoing disputes. The concept is governed by the principle of rule of law and the common law principle of legality. The focus is mainly on judicial review since it is the most regularly used forum for challenging public authorities.

Germany

Germany has a more comprehensive legislation in the PIL system and the relevant provisions of PIL are included in the Constitution of Germany, Administrative Procedure Law, Civil Procedure Act and the Anti-Unfair Competition Law. It is referred to as public action in the German Constitution. The German system of constitutional claim encompasses private parties. This means that any single individual has the possibility to directly address the Constitutional Court. The Constitution empowers German citizens to approach the German Constitutional Court to challenge unconstitutional laws. The Courts are empowered to declare such laws invalid if they are found to violate the Constitution, regardless of whether the citizens bringing such action are directly or indirectly affected by such infringement.

Appearance in Database

SCI Annual Report

The SCI Annual Report presents data regarding the Letter/Petitions and Writ Petitions (Civil and Criminal) received or filed under PIL in the Supreme Court of India between 1985 to 2024. The data also indicates the number of PILs that were taken up by the Supreme Court suo-moto. The graph presented below reflects the data collected and presented in the Supreme Court’s Annual Report 2023-24[11].

India Environment Portal

The India Environment Portal is a platform which is managed by the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) promoted by the National Knowledge Commission (NKC), Government of India. This portal maintains information on PILs filed in relation to environmental subjects, animal rights and wildlife management. It contains reports, court cases, news about PILs specific to this subject.

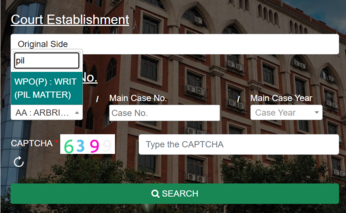

High Court Websites

Bombay High Court

Allahabad High Court

Calcutta High Court

Chhattisgarh High Court

DAKSH Dashboard[12]

The Daksh High Court Writ Dashboard provides an analysis of eCourts data regarding the filing of cases under the category of PILs. It reflects the number of PILs received across High Court between 2010 to 2021.

Research that engages with PIL

- Anti Corruption by Fiat: Structural Injunctions and Public Interest Litigation in the Supreme Court of India[13]“Anti Corruption by Fiat: Structural Injunctions and Public Interest Litigation in the Supreme Court of India” by Chintan Chandrachud examines the Supreme Court's engagement with PIL to address systemic corruption through structural injunctions. Structural injunctions refer to a court issuing a series of interim orders over a period of time in an effort to stimulate institutional reform. It highlights both the potential and limitations of using judicial processes to address deep-rooted institutional challenges.

- On an Average, the Court Receives over 25,000 PILs a Year[14]This article by Gauri Kashyap and Ayushi Saraogi, published in the Supreme Court Observer website, analyses the number of Public Interest Litigation (PIL) cases filed before the Supreme Court between 1985 and 2019. It also presents a quantitative comparison of the nature of PILs filed before the Court. The data indicates that the rate at which PILs are filed is rising.

- Public Interest Litigation in India: Overreaching or Underachieving?[15]“Public Interest Litigation in India: Overreaching or Underachieving?” by Varun Gauri, published by The World Bank, Development Research Group in November 2009 analyses the criticisms of public interest litigation in the context of concerns regarding separation of powers, judicial capacity, and inequality. The study reflects that the practice of PIL in India is a double-edged sword. While it contributes to democratizing justice and making it more accessible, its effectiveness depends on balancing judicial activism with restraint, ensuring that the judiciary complements rather than supplants the role of other democratic institutions.

- Courting the People: Public Interest Litigation in Post-Emergency India[16]“Courting the People: Public Interest Litigation in Post-Emergency India” by Anuj Bhuwania, traces the rise of PIL as a way to remedy the fundamental rights violations during the 1970s in the immediate aftermath of the Emergency, through the ingenuity of a Supreme Court. The work critiques the transformation of the judiciary into a more activist institution and delves into the consequences. It highlights the concern of how what was initially used as a tool for social justice expanded, blurring the lines between judicial and executive functions.

- Environmental Justice in India: A Case Study of Environmental Impact Assessment, Community Engagement, and Public Interest Litigation[17]“Environmental Justice in India: A Case Study of Environmental Impact Assessment, Community Engagement, and Public Interest Litigation” by Ariane Dilay, Alan P. Diduck, and Kirit Patel, examines how Environmental Justice (EJ) principles are manifested in India, with a specific focus on three critical mechanisms: Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA), community engagement, and Public Interest Litigation (PIL). The paper presents case studies that reveal gaps in implementing EIA norms and demonstrate how PILs have been used both effectively and ineffectively to advance environmental justice.

Challenges

In recent times, it has been observed that the use of PILs has strayed from their intended purpose. The practice of PIL has, although expanded the access to justice, also expanded the judicial power, without putting in place a proper system of checks and balances. This form of judicial activism threatens due process. The practice now involves more political angles and hence are driven by political agendas, rather than the intent to do justice.

It has also been observed that in dealing with PILs, there has been hesitance on the part of the judiciary in passing comprehensive orders that cannot be easily overturned. This strays away from the intended purpose of adjudicating PILs to bring in effective change by addressing matters of public concern.

There also exists the problem of filing frivolous petitions, without showing that there has been a violation of fundamental rights. This gives rise to the possibility of taking up the Court’s time and diverting it from meritorious petitions that require the Court’s attention. Other than the concern of time, there also lies the concern of whether the Supreme Court is as PIL- friendly or PIL-conscious as it used to be. Even though the number of PIL filings has been on an upward trajectory over the last decade, it has not often translated to relief for petitioners who challenge the government.

Synonymous Terms

Public interest litigation (PIL) is also commonly referred to as Social Action Litigation (SAL), Social Interest Litigation (SIL), and Class Action Litigation (CAL). They indicate the same idea of taking legal actions to enforce public interest.

References

- ↑ Mumbai Kamgar Sabha v. Abdulbhai Faizullabhai, (1976) 3 SCC 832.

- ↑ Hussainara Khatoon v. State of Bihar, 1980 SCC (1) 81.

- ↑ The Supreme Court Rules, 2013

- ↑ S P Gupta v. Union of India, 1981 Supp SCC 87.

- ↑ Supreme Court Guidelines

- ↑ The High Court of Karnataka (Public Interest Litigation) Rules, 2018

- ↑ Maintainability of Public Interest Litigation Rules, 2010

- ↑ Himachal Pradesh High Court Public Interest Litigation Rules, 2010

- ↑ Orissa High Court Public Interest Litigation Rules, 2010

- ↑ Delhi High Court (Public Interest Litigation) Rules, 2010

- ↑ Supreme Court’s Annual Report 2023-24

- ↑ DAKSH High Court Dashboard

- ↑ Chintan Chandrachud, "Anticorruption by Fiat: Structural Injunctions and Public Interest Litigation in the Supreme Court of India", (2018) 14(2) Socio-Legal Review 170

- ↑ Gauri Kashyap and Ayushi Saraogi, "On an Average, the Court Receives over 25,000 PILs a Year"

- ↑ Varun Gauri, “Public Interest Litigation in India: Overreaching or Underachieving?”, The World Bank, Development Research Group (November 2009)

- ↑ Anuj Bhuwania, "Courting the People: Public Interest Litigation in Post-Emergency India”

- ↑ Ariane Dilay, Alan P. Diduck, and Kirit Patel, "Environmental Justice in India: A Case Study of Environmental Impact Assessment, Community Engagement, and Public Interest Litigation”, IMPACT ASSESSMENT AND PROJECT APPRAISAL (2020), VOL. 38, NO. 1, 16–27