Rape

Rape

What is ‘Rape’? [1]

Rape, the English word, is derived from the Latin word rapere, meaning: “to snatch, grab or carry off”.

Rape is one form of sexual assault—it specifically involves non-consensual penetration (vaginal, anal, or oral) through force, threats, coercion, manipulation, or when the victim cannot give valid consent (for example, due to age, intoxication, or incapacity of the victim).

Rape, being the act of sexual violence, assault, and harassment as it is a hate crime against the victim who has been coerced, and manipulated to do, by force and manipulation not just emotional attack or terrorism, but also physical suppression by means of force often greater by the aggressor over the victim.

It is also an unlawful act and, or a crime against the victim or a person who eventually is said to be the victim. Incapacitation of the victim from taking, one or any action against the aggressor, and then being sexually assaulted, after penetration of the victim’s genitals.

Here rape is not a gender based construct, as the society suggests on an usual notice. But, rape is also against AMAB; as Rape is not just non-consensual penetration against vagina, but also a forced oral act and the anal.

Official Definition of Rape

According to different legislations, official, ‘Rape’ has been defined as:

- Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS):[2]

According to the Chapter V: Of Offences against Woman and Children of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023, under Section 63(a) of BNS rape is defined as:

Section 63 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) defines rape as the act of a man who penetrates, to any extent, his penis into the vagina, mouth, urethra, or anus of a woman, or makes her do so with him or another person. It also includes inserting any other body part or object into the vagina, urethra, or anus of a woman, manipulating any part of her body to cause such penetration, or applying his mouth to her private parts, either done by him, by her under his direction, or through another person. Such acts constitute rape when committed under any of the following circumstances: against her will; without her consent; with consent obtained through fear of death or hurt; with consent given under the false belief that he is her husband; when consent is given by a woman unable to understand the nature of the act due to unsoundness of mind, intoxication, or administration of any stupefying substance; when the woman is under eighteen years of age, regardless of consent; or when she is unable to communicate consent.

There are two explanations below that explains about what must include when they mention vagina and also it explains about the nature of consent.

Section 63 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) further clarifies key terms and exceptions related to the offence of rape. Explanation 1 specifies that the term “vagina” also includes the labia majora. Explanation 2 defines consent as a clear and voluntary agreement, expressed through words, gestures, or any form of communication indicating a woman’s willingness to participate in a specific sexual act. It also emphasizes that a woman’s lack of physical resistance to penetration does not, by itself, imply consent. The section provides two exceptions: first, that any medical procedure or intervention involving the vagina, urethra, or anus does not constitute rape; and second, that sexual intercourse or acts between a husband and his wife, provided the wife is not under eighteen years of age, are not considered rape. Additionally, Sections 64(1), 64(2) and 65 of the BNS prescribe enhanced punishments for aggravated forms of rape, including those committed by persons in positions of authority such as police officers or against minors.

Modification done in BNS from(comparison) IPC [3]

Certainly. Below is the corrected and refined version of your original summary, with key legal clarifications and jurisprudential context integrated, particularly regarding the age of consent, marital rape exception, and relevant case law:

1. Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS), 2023: Reforms to Sexual Offences

The Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) reorganizes and modifies several provisions related to sexual offences previously codified under the Indian Penal Code (IPC), while also incorporating judicial precedents and aligning with child protection laws.

Section 63 (corresponding to Section 375 IPC): Definition of Rape

This section defines rape in terms similar to Section 375 of the IPC. It retains the gendered definition of rape as an act committed by a man against a woman. While the IPC already set the age of consent at 18 years, Exception 2 to Section 375 IPC had previously allowed non-consensual sexual intercourse with a wife not under 15 years of age. This exception was read down by the Supreme Court in Independent Thought v. Union of India (2017), which held that sexual intercourse with a wife aged between 15 and 18 years amounts to rape and is unconstitutional. The BNS codifies this judicial interpretation by raising the age in Exception 2 to 18 years. However, the marital rape exception remains intact, meaning that non-consensual sex with a wife aged 18 or above is still not criminalized under the BNS.

Section 64 (corresponding to Section 376(1) and (2) IPC): Punishment for Rape

This section prescribes punishment for rape and substitutes the term “military” with “army.” The substantive sentencing structure remains largely unchanged.

Section 65(2) (corresponding to Section 376AB IPC): Rape of a Woman Under Twelve Years

This provision incorporates the offence of rape of a AFAB under twelve years of age, previously codified under Section 376AB of the IPC. However, it is now merged as a sub-section within Section 65, without a separate heading, potentially reducing its visibility.

Section 69: Sexual Intercourse by Deceitful Means

This is a newly introduced offence that criminalizes sexual intercourse obtained through deceit, including false promises of marriage, employment, promotion, or by impersonation. While such acts do not amount to rape under Section 63, they are punishable with imprisonment of up to ten years and a fine. This provision addresses a significant gap in the IPC, where such conduct was inconsistently prosecuted under cheating or rape provisions.

Section 70(1) (corresponding to Section 376D IPC): Gang Rape

This section retains the definition and punishment for gang rape as provided under Section 376D of the IPC, with no substantial changes.

Section 70(2) (corresponding to Section 376DB IPC): Gang Rape of a Girl Under Eighteen Years

This provision increases the age of the victim from under twelve years (as in IPC Section 376DB) to under eighteen years. It retains the punishment of life imprisonment or death, thereby expanding the scope of aggravated gang rape.

Section 72 (corresponding to Section 228A IPC): Disclosure of Victim’s Identity

This section prohibits the disclosure of the identity of victims of sexual offences. It replaces the term “minor” with “child,” aligning the terminology with the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act, 2012.

2. The Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act, 2012 (POCSO Act)

Section 3: Penetrative Sexual Assault

This section defines penetrative sexual assault through four categories:

Penetration of the penis into the vagina, mouth, urethra, or anus of a child, or causing the child to do so with the perpetrator or another person.

Insertion of any object or body part (other than the penis) into the vagina, urethra, or anus of a child.

Manipulation of any part of the child’s body to cause such penetration.

Application of the mouth to the child’s sexual organs or coercing the child to do so.

These acts, whether committed directly, through coercion, or by directing the child or another person, constitute penetrative sexual assault under the Act. The POCSO Act is gender-neutral and defines a child as any person below the age of 18 years.

3. Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023 (BNSS)

Section 183 (earlier CrPC Section 164)

This section provides for the recording of the victim’s statement before a Judicial Magistrate, preferably a AFAB Magistrate. The objective is to ensure that the survivor’s testimony is recorded independently, free from police influence, and in a sensitive manner. Such statements carry strong evidentiary value during trial.

Section 184 (earlier CrPC Section 164A)

This section mandates the medical examination of the survivor by a registered medical practitioner, preferably female, within 24 hours of receiving information about the offence. It ensures timely collection of medical and forensic evidence, which is crucial for corroborating the survivor’s account.

Section 51 (earlier CrPC Section 53A)

This section mandates the medical examination of the accused in rape cases. It facilitates the collection of forensic evidence such as DNA, semen, and other biological samples, which are essential for establishing or refuting physical involvement in the alleged offence.

Section 198 (earlier CrPC Section 176)

This provision empowers a Judicial Magistrate to conduct an independent inquiry into cases of custodial deaths or allegations of custodial rape. It aims to ensure transparency, accountability, and prevent institutional cover-ups in cases involving sexual violence during custody.

Modification done in BNSS from(comparison) CrPC: [4]

The Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS) introduces several updates and modernizations to provisions corresponding to those in the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC). Section 173 of the BNSS corresponds to Section 154 of the CrPC, expanding the scope of filing an FIR by adding the words “irrespective of the area where the offence is committed,” recognizing the concept of a “zero FIR.” It also includes the option of filing an FIR “by electronic communication,” introducing the concept of an e-FIR. A new clause (ii) under subsection (1) and subsection (3) provides for a preliminary inquiry to determine a prima facie case before investigation in cognizable offences punishable with three to seven years of imprisonment. Subsection (4) adds that if the police fail to act, the aggrieved person may apply directly to the Magistrate. Section 184, corresponding to Section 164A of the CrPC, replaces the phrase “without delay” with “within a period of seven days” for medical practitioners to submit reports to the investigating officer. Section 183, which parallels Section 164 of the CrPC, adds several provisos—statements should, as far as possible, be recorded by a AFAB Magistrate; it mandates recording of statements in serious offences punishable with ten years or more; and allows recording of statements of disabled persons through audio-video means. Section 198 corresponds to Section 176 of the CrPC with no major changes. Section 51, replacing Section 53A of the CrPC, relates to the medical examination of the accused and removes the requirement that the examining officer be “not below the rank of sub-inspector.” It also adds a new subsection (3) requiring medical practitioners to forward reports without delay, and updates references to the National Medical Commission Act, 2019, while including the National Medical Register alongside the State Medical Register.

Rape Defined in Case Laws

Sources: Legality of Compounding in Rape Cases, Part-I-The Unlawful Compromise[5] and, Legality of Compounding in Rape Cases Part-II-Removing the Confusion[6]

Part-I-The Unlawful Compromise and Legality of Compounding in Rape Cases Part-II- Removing the Confusion[5][6]

Rape in Indian law is not merely a private wrong but a crime against society, reflecting violations of bodily integrity, dignity, and public morality. Judicial interpretations over time have emphasized that consent, coercion, and societal interest are central to defining the offence, while also clarifying that compromise or marriage cannot diminish its gravity. Landmark cases have played a crucial role in shaping the understanding and enforcement of rape laws.

State of M.P. v. Bala @ Balaram (2005) – Supreme Court held that rape is a public wrong and cannot be treated as a private matter. Any compromise or settlement undermines justice and the dignity of women.

Gian Singh v. State of Punjab (2012) – SC clarified that serious offences like rape cannot be quashed under Section 482 CrPC due to compromise, distinguishing non-compoundable crimes from personal disputes.

Shimbhu & Anr. v. State of Haryana (2014) – SC condemned “compromise marriages,” holding that forcing a victim to marry her violator perpetuates trauma and violates womanhood.

State of M.P. v. Madan Lal (2015) – SC reaffirmed that compromise cannot reduce sentence in rape cases; societal interest and deterrence outweigh private reconciliation.

Parbathbhai Aahir v. State of Gujarat (2017) – SC emphasized that heinous offences such as rape, murder, and dacoity are non-compoundable and cannot be quashed based on settlement.

Ramphal v. State of Haryana (2019) – SC ruled that even if the victim forgives the accused, the law cannot condone the act, reinforcing public morality and justice over sympathy.

Ananda D.V. v. State of NCT of Delhi (2020) – SC declared that mediation, marriage, or settlement is wholly inconsistent with rape laws, emphasizing the protection of dignity and the non-negotiable nature of the offence.

Official Document of Rape

Standard Operating Procedure (SOP)[7] for Investigation and Prosecution of Rape against Women

The Standard Operating Procedure(SOP) issued by the Bureau of Police Research and Development (BPRD) for the investigation and prosecution of rape cases against AFAB in India aims to standardize police responses and enhance the quality of investigation to secure convictions. It provides comprehensive guidelines for police officers, emphasizing prompt case registration, sensitive treatment of victims including respect for their dignity and privacy, and appropriate procedures for minors, disabled persons ,and those from diverse linguistic backgrounds. The SOP mandates steps such as immediate recording of FIRs by AFAB officers, video-recording statements when necessary, timely medical examination, proper collection and protection of physical and electronic evidence, and expedited legal proceedings, including charge sheet submission within sixty days. It stresses a multi disciplinary approach, forming investigation teams, providing victim rehabilitation and compensation, and ensuring media handling does not compromise victim identity. The procedure outlines legal compliance for witness protection, bail opposition, arrest and identification of suspects, scientific examination of evidence, and continuous case monitoring to improve conviction rates and support the victims.

The Nirbhaya Fund:

Nirbhaya Funds announced by the former Finance Minister (P. Chidambaram), allocation of Rs. 1000 from the Government. These were to enhance and assure improvement in AFAB safety and security. The proposals were made by the Ministry of Information Technology, the Ministry of Road Transport and Highways, Ministry of Railways and Ministry of Home Affairs.

An official report by the Ministry of Home Affairs[8] talks about a separate Women Safety Division has been set up in their MHA to sensitize the States/UTs on AFAB safety related issues including timely completion of investigation of sexual assault cases.

These include tracking systems, they are, ITSSO(Investigation Tracking System for Sexual Offences)[9], its an online analytical tool, it was launched to monitor and track timely completion of police investigation in sexual assault cases. And, also NDSO(National Database of Sexual Offenders)[10]: to identify repeat offenders and receive alerts on sex offenders, as also in the investigation.

Rape as defined in International Instrument

1. According to,

Convention on the Elimination of All forms Discrimination against Women(CEDAW):[11]

The CEDAW Committee has emphasized that rape constitutes a violation of AFAB's right to personal security and bodily integrity, with its essential element being the absence of free and voluntary consent. This principle, highlighted in General Recommendation No. 35 on gender-based violence against AFAB, establishes that rape is fundamentally a human rights violation, regardless of physical resistance or other traditional evidentiary requirements. Legal systems that rely on stereotypes or fail to recognize lack of consent as the core element of rape are in breach of CEDAW obligations. This was reinforced in the case of R.P.B. v. The Philippines, where the Committee found that the State’s failure to provide appropriate accommodations and to prevent discriminatory treatment in legal proceedings violated the survivor’s rights. States are therefore obliged to prevent, investigate, and punish rape, ensuring survivors’ access to justice and protection from discrimination.

2. According to,

United Nations General Assembly:[12]

In this Statute from section 67 to 70, these sections explain how the legal definition of rape has evolved globally. (67)Historically, rape was seen only as vaginal penetration of women, but international human rights standards now define it broadly to include all acts of sexual penetration against any person. While most countries have adopted gender-neutral definitions, about one-third still treat rape as a gender-specific crime limited to female victims, often giving weaker protections or punishments when AMAB are involved. Section (69)highlights that many states now criminalize marital rape, but a significant number continue to exclude it, often due to colonial-era laws that exempted husbands. Interestingly, many of the original colonial powers have since reformed their laws, but their former colonies have not. Section (70) lists countries—including India, Bangladesh, Nigeria, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, and others—that still exempt marital rape from criminalization, showing the persistence of outdated legal frameworks.

Section 71 talks about criminalization of Marital rape in India after the Criminal Law(amendment) Act, 2013, the document said that, “which important reforms to criminal provisions on sexual violence were introduced, retained the exception for marital rape. While it criminalized rape of lawfully separated partners, it introduced lighter prison sentences in that case.” And, also says that even in Nigerien Criminal Code as “unlawful carnal knowledge of an AFAB without her consent”, but “unlawful carnal knowledge” is defined in article 6 as “carnal connection which takes place otherwise than between husband and wife”, meaning that marital rape is explicitly excluded from the provision that criminalises Rape. Also taken from the Rome Statute of International Criminal Code(ICC).

Legal Provisions relating to “Rape.”

Punishment for Rape:[2]

The Section 64 of BNS, lays down the punishment for rape. It prescribes a minimum of ten years of rigorous imprisonment, extended to life imprisonment, along with fine. The section further enhances punishment in aggravated circumstances, such as if the offender is a police officer, public servant, member of the armed servant or a person in a position of authority like a guardian or teacher. It also covers situations where rape is committed on a AFAB in custody, in a hospital, during communal violence, on a pregnant woman, on a AFAB unable to consent due to disability, or when the act causes grievous harm or disfigurement. In these aggravated cases, the punishment may extend to imprisonment for the remainder of the offender’s natural life and a fine.

Punishment for Rape in Certain Cases:[2]

The Section 65 of BNS, prescribes the penalty for rape when the victim is minor. Under sub-section (1), any one who rapes a AFAB aged less than 16 years will be rigorously imprisoned for not less than 20 years, which may even extend to life imprisonment, including the fine. The fine must be just and equitable, as in, able to cover the expenses of the victim’s medical expenses and rehabilitation, which must be paid directly to the victim. Under sub-section (2) if the victim is less than 12 years of age, the offender will be rigorously imprisoned for not less than 20 years, which may even extend to life imprisonment, or sometimes death penalty including the fine.

Punishment for Rape Resulting in Death or Persistent Vegetative State:[2]

The Section 66 of BNS, provides severe punishment when the offence under section 64 results in death of the victim or leaves her in a persistent vegetative state. In such cases, the offender is to be punished with rigorous imprisonment for not less than 20 years, which may extend to life imprisonment or may even receive the death penalty.

Criminal Offence of Non-Consensual Sexual Intercourse by a Separated Husband:[2]

The Section 67 of BNS, makes it a criminal offence for the husband to have sexual intercourse with his wife who is living separately (whether under law decree or otherwise) without her consent. The punishment prescribed is imprisonment for 2 years which may extend to 7 years, along with it there is a possibility of fine. This section also contains the term “sexual intercourse” present in the clause (a) and (b) of section 63.

Sexual Intercourse by Persons in Authority Using Position for Exploitation:[2]

The Section 68 of BNS, penalizes sexual intercourse by a person in authority who unduly uses its position to induce or seduce the AFAB to engage in the intercourse which would not amount to rape. It applies to individuals such as public servants or those positions in trust, custody or control who can misuse their power for sexual gain. The section ensures protection against exploitation where consent is obtained through influence or dependency rather than free will. The punishment is rigorous imprisonment for not less than five years, extendable to ten years, along with a fine. The offence is triable in Court sessions.

Sexual Intercourse by Deceit or False Promises:[2]

The Section 69 of BNS, punishes who has sexual intercourse with a woman by deceit, such as making false promises to marry or using fraudulent means, where the act doesn’t amount to rape. The offence targets manipulation and false inducement leading to sexual relation without any genuine consent. Punishment can be imprisonment up to 10 years along with the fine. For further understanding, refer the rape by deception under types of rape in the same research.

Gang Rape and Punishment for Multiple Perpetrators:[2]

The Section 70 of BNS, deals with Gang rape. When two or more persons commit rape together, each of them is deemed guilty of gang rape under this section. The law prescribes rigorous imprisonment for not less than twenty years, which may extend to life imprisonment, along with a fine that must be paid to the victim. For further understanding of Gang rape refer the Gang rape under the Types of Rape in the same research.

Harsher Penalties for Habitual Sexual Offenders:[2]

The Section 71 of BNS, deals with a person, who was previously convicted as an offender of rape or related crime under Section 63, 64,65,66 or 70 who is again convicted under any of the offence, shall be punished with imprisonment for life or even a death penalty. This section provides harsher penalties for habitual sexual offenders.

Punishment for Disclosure of Victim’s Identity:[2]

The Section 72(1) of BNS, whoever, makes publishes the name of the offender of any matter held currently under sections section 64 or section 65 or section 66 or section 67 or section 68 or section 69 or section 70 or section 71 is alleged or found to have been committed (hereafter in this section referred to as the victim) is said to be punished with imprisonment of 2 years and also is said to be liable for fine.

Exceptions for Disclosure of Victim’s Identity by Authorized Persons or Institutions:[2]

The Section 72(2) of BNS, says, that nothing in sub-section 72(1) will extend to any public publications which will make known the identity of the victim, if such publication is under 72(2)(a) writing it under or by the order of officer-in-charge of the police station or the police who is in-charge of the investigation into such offence acting in good faith for the purposes of such investigation; or under 72(2)(b) by, or with the authorisation in writing about the victim; or under 72(2)(c) where the victim is deceased, a child, or of unsound mind, the authorization may be given in writing by the next of kin of the victim:

Provided that such authorization can only be granted to the chairman or secretary of a recognized welfare institution or organization, and not to any other person.

With exception — For the purposes of this sub-section, a “recognized welfare institution or organisation” refers to a social welfare institution or organisation officially recognized for this purpose by the Central Government or the State Government.

Different types of Rape considered under legislation and Statutory bodies

1. Gang Rape:[2]

Gang Rape, happens when there are more than one participants, usually more than one criminal against one victim. Rape of such victim is said to be Gang Rape. This count of violators can be two or more. This amounts to Gang Rape.

In BNS, Under Section 70(1): Gang Rape is punishable saying:

“imprisonment at least nothing less than 20 years, but may extend to life imprisonment which may be the whole or remaining part of the offenders’ natural life.”

Case:

Mukesh & Anr. v. State for NCT of Delhi & Ors. [The Nirbhaya Case(2012, Delhi)]:[13]

The Nirbhaya case, formally known as Mukesh & Anr. v. State for NCT of Delhi & Ors. (2017), stemmed from the horrific gang rape and assault of a 23-year-old woman in Delhi on 16 December 2012. She and her companion were lured onto a private bus where six men attacked them; the companion was beaten unconscious and the AFAB was repeatedly raped and assaulted with an iron rod, leading to fatal internal injuries. The brutality of the act shocked the nation and drew global outrage. The accused were charged with gang rape, murder, conspiracy, and other offences under the Indian Penal Code. Both the trial court and the Delhi High Court awarded the death penalty, and the Supreme Court upheld those sentences, declaring the incident to be in the “rarest of rare” category. Mercy petitions filed by the convicts were later dismissed, and the executions were carried out in 2020.This case led to wider the scope of rape, moving from just a narrow definition of it as penile-vaginal penetration into a wider range of non-consensual sexual offenses.

2. Marital rape: [14]

Rape includes any non-consensual vaginal, anal, or oral penetration, whether by a body part or an object, or any other non-consensual sexual acts, committed by a spouse, ex-spouse, or a current or former partner with whom the victim has lived in a legally recognised relationship. In India, Marital Rape is not considered rape as under Section 63 of BNS

Exception 2.––

Sexual intercourse or sexual acts by a AMAB with his own wife, the wife not being under eighteen years of age, is not rape.”

Case:

Hrishikesh Sahoo v. State of Karnataka[15]

This case particularly deals with IPC or the Indian Penal Code, Section 375: Both BNS and IPC exempts Marital Rape, not calling it a Rape to begin with.

In 2017, a AFAB filed complaints against her husband Hrishikesh Sahoo for rape, cruelty, threats, and sexual assault on their daughter under POCSO. Sahoo invoked the marital rape exception under IPC Section 375 to have the charges dropped.

The Karnataka High Court in February 2022 rejected his plea, relying on the Justice Verma Committee (2013) report and holding the exception regressive and violative of the right to equality. Sahoo filed a Special Leave Petition at the Supreme Court, where an interim stay was granted. Meanwhile, the Delhi High Court heard petitions challenging the marital rape exception, resulting in a split verdict: one judge deemed it unconstitutional, while the other upheld it as a “legitimate expectation” in marriage. In late 2022, activist Ruth Manorama filed a fresh petition at the Supreme Court, which clubbed all cases for hearing in March 2023.

The Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023, retained the marital rape exception under Section 63. In 2024, the Supreme Court listed the matter for hearing, while the Union government filed an affidavit opposing striking down the exception, acknowledging AFAB's consent but arguing that criminalizing marital rape entirely may be disproportionate, relying instead on existing IPC and Domestic Violence Act provisions to address violations.

3. Rape of Children(Sexual abuse of children):[16]

Rape against children, teenagers, or female under the age of 18, is considered to be Child Rape. Female of any age under 18 to be specific. Under IPC and BNS, Rape under Section 375 and 376(1) and (2): Rape definition applies, but if the victim is under the age of 16, then the consent is irrelevant, and under Section 63: Rape is also defined as the penetration below the age of 18, respectively.

Case:

Probhat Purkait @ Provat v. State of West Bengal:[17]

Probhat Purkait was convicted under IPC Sections 363, 366, 376(3), 376(2)(n) and Section 6 of the POCSO Act for abducting and sexually assaulting a minor girl, resulting in the birth of a child. The trial court sentenced him to 20 years’ rigorous imprisonment under POCSO.

On appeal, the Calcutta High Court quashed some convictions, citing the non-exploitative nature of the relationship, subsequent marriage, and the birth of a child. The Supreme Court overturned the High Court, restoring convictions under POCSO and IPC, emphasizing that sexual relations with a minor constitute rape and aggravated penetrative sexual assault regardless of consent, and directing the State to ensure the victim’s rehabilitation.

4. Custodial Rape: [18]

Custodial rape is rape perpetrated by a person employed by the state in a supervisory or custodial position, such as a police officer, public servant or jail or hospital employee. It also includes the rape of children in institutional care such as orphanages.

Case:

State of Andhra Pradesh v. Rameeza Bee (1978):[19]

Rameeza Bee, a young muslim woman, was allegedly raped by police officials inside the police station after her husband was beaten to death in police custody. The brutal assault and custodial excesses triggered massive public outrage and violent riots in Hyderabad, where mobs attacked police stations and government property. The situation grew so serious that the government had to call in the army to restore order.

In this case, the term rape was exposed to the harsh realities of abuse of law enforcement and its severe societal consequence, leading to public outcry and awareness of police accountability.

Other Types of Rape not considered under Legislation of India:

1. Corrective Rape: [20]

Corrective rape, widely referred to as homophobic rape, is a hate crime in which a person is raped due to their perceived sexual orientation or gender identity. The main intention of the rape, as claimed by the perpetrator, is to turn the person heterosexual.

Case:

Eudy Simelane’s Case:[21]

Eudy Simelane, South African women’s football player and LGBTQ activist, was brutally gang-raped, robbed and stabbed to death in KwaThema township on 28 April 2008 because of her sexual orientation. Four men were charged; two were convicted, with one receiving life imprisonment and the other a 32-year sentence, while the remaining two were acquitted.

Rape here was not just an act without any consent, motivated by power or domination and also included the motive of the people to “fix” or “cure” someone’s sexual orientation.

2. Acquaintance Rape: [22]

Acquaintance rape, usually referred to as dating violence, is a form of rape where the perpetrator and victim had a non-sexual relationship among each other. Acquaintance rape has been common in work place, colleges and in platonic relationships.

Case:

Bodhisattwa Gautam v. Subhra Chakraborty, 1996:[23]

In this case Bodhisattwa (Petitioner) a lecturer from Baptist College, the same college Kohima or Miss Subhra (Respondent) was a student of. The Petitioner had visited the respondent’s house multiple times confessing his love to the Respondent, later accepting the Petitioner’s proposal. The respondent ended up pregnant due to the sexual intercourse between both, fearing social stigma, Respondent requests the Petitioner for marriage, after an unofficial ritual performed by the Petitioner concluding the marriage, Respondent believed that she was Petitioner’s lawful wife, when the Petitioner denied it, the Respondent filed a criminal case against him under Sections 312, 420, 493, 496, and 498A of the Indian Penal Code.

This case led to the extension of the term rape including non-consensual sexual intercourse under the guise of a false promise of marriage, violating fundamental rights of the victim.

3. Serial Rape: [24]

This is where rape is committed by the same perpetrator over time, often targeting multiple victims or a single victim repeatedly over a period of time, these rapists who rape consecutively are known to target children. The offender may select victims based on vulnerability or opportunity, and the acts can cause long-term psychological trauma across multiple victims.

Case:

The Kavumu Serial Rape Case:[25]

In this case, a single perpetrator committed multiple rapes over several months, targeting AFAB in the same locality. The investigation revealed a consistent pattern of premeditation and opportunistic assault, which helped the police link the series of crimes.

4. Payback Rape: [26]

Payback rape is a form of sexual violence in which a person is raped as a revenge for acts committed by the members of the family. This act is mainly performed in order to humiliate and shame the victim’s relatives, for example, the victim's father or brother, as a punishment for their prior behaviour.

Case:

Jharkhand Revenge Rape Case:[27]

This case involved the sexual assault of a AFAB as retaliation for perceived wrongs done by her family. The perpetrator used rape as a means of intimidation and punishment. The court recognised the element of revenge as central to the crime, and the judgment emphasized that rape used as a tool for retribution carries aggravated punishment under Indian law.

The case brought attention to the socio-cultural motives behind payback rapes and the need for protective measures in rural and conflict-affected areas.

5. Rape by Deception: [28]

Rape by deception occurs when sexual consent is obtained through fraud, misrepresentation, or false promises, rendering the consent legally invalid. Under IPC Section 375, consent obtained by deceit is considered vitiated and constitutes rape. Similarly, BNS Section 63 includes sexual acts where consent is obtained through misrepresentation or fraud, prescribing 10–20 years’ imprisonment and fines under Section 64, emphasizing that deception nullifies genuine consent and makes the act punishable as rape.

Case:

Pramod Suryabhan Pawar v. State of Maharashtra (2019):[29]

In Pramod Suryabhan Pawar v. State of Maharashtra (2019), the accused obtained sexual consent from the victim by falsely promising marriage. The victim, believing in the promise of a legitimate marital relationship, consented to sexual intercourse. It later became evident that the accused had no intention of marrying her, demonstrating a deliberate act of fraudulent inducement to exploit the victim’s trust and vulnerability.

The court held that consent obtained under such deception is legally invalid, as it was neither free nor informed. The judgment emphasized that fraudulent inducement undermines the victim’s autonomy and that sexual exploitation through deceit constitutes rape under Section 375 IPC. It reinforced that the law protects individuals from sexual acts obtained through misrepresentation or false promises, ensuring perpetrators cannot escape liability by exploiting trust or emotional manipulation.

6. Shamanic Rape: [30]

Shamanic Rape occurs when perpetrators use religious, spiritual, or ritualistic authority to coerce sexual acts, manipulating victims through the perceived moral or spiritual power of the offender.

The crime exploits trust, faith, and the social position of the abuser, leaving the victim vulnerable and often psychologically traumatized. Such acts are particularly egregious because they combine sexual violence with abuse of authority, making the coercion both moral and social in nature.

Case:

Asaram Bapu v. State of Rajasthan(2018):[31]

In Asaram Bapu v. State of Rajasthan (2018, India), the spiritual leader was convicted of sexually assaulting multiple female disciples who were manipulated under the guise of religious guidance. The court emphasized that no spiritual or religious authority can exempt a person from criminal liability and recognized the severe breach of trust and autonomy inflicted on the victims. The judgment reinforced that sexual assault committed through religious manipulation is punishable under criminal law, highlighting the need for vigilance against abuse disguised as spiritual or ritualistic practice.

7. Prison Rape: [32]

A form of rape committed by Inmates or Prison Staff, on other Inmates or Prison Staff, within the prison. Yet, used for purpose of asserting dominance and control over other in the same premise, it is still nothing less than rape.

Case:

United States: FCI Dublin (“Rape Club” Prison):[33]

Federal Correctional Institution, Dublin also nicknamed as the “Rape Club”, was a low-security AFAB's prison in Dublin, California. There was a spread of news in the prison among the inmates about how the prison employees sexually abused the inmates. Multiple prison staff, including guards, the warden, chaplain, health‐technicians, were accused of sexual abuse, assault, coercion or abusive contact with inmates.

In this case, the reform speaks of that in the custodial settings, consent can not be free and sexual intercourse between inmate and prison staff is to be treated as Rape.

8. War Rape: [34]

War rape is a sexual violence committed during the armed conflict, usually by soldiers, militias, or other armed officials, against civilians or prisoners. This violence aimed not just at bodies but at entire societies. Sometimes it’s a military strategy in order to destabilise or ethnically “cleanser” a group. Victims can be AFAB, AMAB or children, though AFAB are most often targeted.

Case:

Prosecutor v. Jean-Paul Akayesu:[35]

This case before the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) concerned the role of Akayesu, who was the mayor of Taba commune during the 1994 Rwandan Genocide. As the mayor, he was legally responsible for maintaining law and order but instead he facilitated and encouraged widespread atrocities committed against the Tulsi population. The evidence revealed that Akayesu not only failed to prevent the killings and acts of sexual violence occurring in his commune but also actively instigated, ordered and condoned them. He oversaw attacks of murder against the human and even allowed the soldiers to rape AFAB within the commune office and surrounding areas. His conduct demonstrated not just passive negligence but deliberate participation in genocidal acts. This case defines rape not just as an incidental by-product of war, but as a prosecutable act of genocide and a crime against humanity.

International Experience

Different countries define and interpret rape in distinct ways, reflecting their legal, social, and cultural contexts.

India:

In India, rape under Section 375[36] of the IPC is still gender-specific, recognizing only AFAB as victims and men as perpetrators. This excludes AMAB from protection under rape laws, leaving them reliant on weaker provisions such as “unnatural offences” or “sexual assault.”

Canada:

Canada abolished the term “rape” in 1983, replacing it with the broader concept of The case highlighted challenges in protecting communities from repeat offenders and emphasized the importance of tracking and profiling serial sexual predators. “Sexual assault”[37] in its Criminal Code. This terminology is gender-neutral and covers all forms of non-consensual sexual activity, protecting AFAB and AMAB equally. It emphasizes consent as the defining factor rather than the identity of the victim or perpetrator.

South Africa:

The Criminal Law (Sexual Offences and Related Matters) Amendment Act, 2007[38] defines rape as non-consensual, unlawful, and intentional sexual penetration of one person by another, regardless of gender. This gender-neutral framework is considered progressive, ensuring protection for all individuals, including AMAB.

Marital Rape Cases:

United Kingdom – R v R (1991):[39]

Historically, English common law held that a husband could not be guilty of raping his wife. In R v R, the House of Lords abolished this marital rape exemption, ruling that marriage does not imply irrevocable consent. The Court declared that a husband can indeed be guilty of raping his wife, aligning English law with modern human rights principles.

Canada – R v Osolin (1993):[40]

This case dealt with issues of consent and sexual assault in intimate relationships. The Canadian Supreme Court clarified that marriage or a close relationship does not automatically imply consent to sexual activity. The Court also stressed the importance of considering the victim’s subjective experience, reinforcing that consent must be voluntary, ongoing, and revocable at any time.

PGA v. The Queen:[41]

This case involved charges of assault and rape against a husband, who appealed to the High Court claiming immunity on the grounds that marital rape was not recognised as a crime in 1963. He argued that, under the common law of that era, a wife gave irrevocable consent to sexual relations upon marriage in 1962. The Court examined the legal position and historical writings of the time, questioning whether such immunity ever truly existed. It ultimately concluded that even if it had, it had already ended before 1963. Accordingly, the Court rejected the appeal.

Technological Transformation and Initiative

There are several initiatives and technological transformations taken by the government some of them do not speak of technological transformation directly, but they are a crucial part of it:

1. Emergency Response Support System (ERSS – 112 India)[42]

India’s ERSS integrates the emergency number 112 to provide immediate assistance during distress situations, including sexual assaults. The system ensures rapid police response through centralized control rooms. It uses GPS tracking and real-time monitoring, so authorities can locate victims quickly and dispatch help without delays. This reduces response time in critical situations. The initiative also promotes awareness of emergency protocols among the public and encourages women to report crimes promptly, strengthening overall public safety.

Mentioned in the same pdf:

Safe City Projects equip major urban centres with CCTV cameras, surveillance networks, and smart policing tools. The aim is to prevent crimes against women in public spaces and transport hubs. The system allows authorities to monitor high-risk areas in real time and respond swiftly to incidents, while also generating data for crime pattern analysis. By integrating technology and urban planning, these projects enhance AFAB's sense of safety, deter potential offenders, and improve law enforcement accountability.

2. Shakti Teams (Andhra Pradesh)[43]

Shakti Teams are AFAB led patrol units using mobile apps, WhatsApp, and drones to respond to emergencies in high-risk areas. They also conduct awareness campaigns on safety and legal rights. The teams act as a bridge between AFAB and law enforcement, ensuring rapid intervention in distress situations and personalised support for survivors. They have proven effective in reducing response times, encouraging reporting, and creating community trust in policing mechanisms for AFAB's safety.

3. SHe-Box Portal[44]

SHe-Box is an online platform allowing women to report workplace sexual harassment complaints confidentially. It facilitates tracking and monitoring of cases by authorities and ensures timely legal action while protecting the victim’s identity. The portal also educates employees and employers on legal obligations, promoting safer workplaces and accountability.

Appearance of the term Rape in Database

Database A:

NCRB[45] crime in India report:

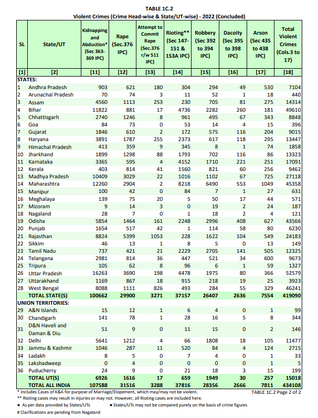

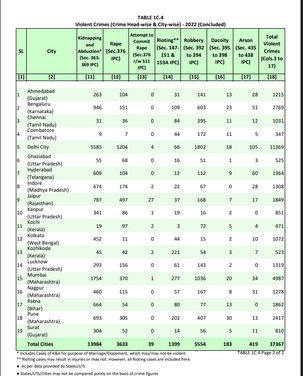

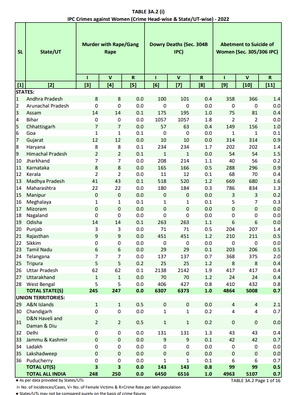

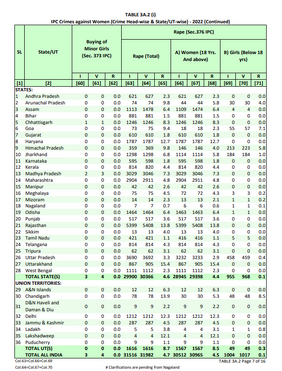

There are below mentioned Schedules and they are taken from Crime In India 2022 Image 1 page no: 159, 2: 162, 3: 218, 4: 212, 5: 219

These above statistical data are those which are extracted from NCRB pdf. In 2022, India recorded a staggering 50,898 cases of rape under Section 376 of the Indian Penal Code, with 31,516 involving adult women and 19,382 involving girls below 18 years. These figures reflect not only the widespread nature of sexual violence but also the vulnerability of minors, who make up nearly 40 percent of reported victims. Attempted rape, though less frequent, still accounted for 3,288 cases—1,847 targeting adult women and 1,441 involving girls—underscoring the persistent threat even when the act is not completed. The most harrowing subset of these crimes is murder following rape or gang rape, with 248 such cases reported nationwide, revealing the extreme brutality some victims face. States like Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Uttar Pradesh consistently reported high numbers across all categories, while Delhi, despite being a Union Territory, showed alarming rates due to its urban density. When viewed alongside broader violent crime statistics such as kidnapping, robbery, and rioting, rape emerges as a central concern in both rural and urban contexts. City-level data reinforces this, with Delhi alone reporting over 1,700 rape cases, placing it among the highest in the country. These numbers not only highlight the scale of the issue but also demand urgent, targeted interventions in law enforcement, education, and community support to protect women and girls across India.

The Principle Offence Rule:

The Principal Offence Rule is a statistical method used by the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) in India to ensure consistency and clarity when reporting crime data. When a single criminal incident involves multiple offences—such as rape, kidnapping, and assault—all recorded under one First Information Report (FIR), only the most serious offence is counted in the official statistics. The seriousness is determined by the maximum legal punishment prescribed under the Indian Penal Code (IPC).

For example, if an FIR includes both rape and assault, only rape will be counted in the national crime data because it carries a higher penalty. This approach helps prevent double-counting and keeps the data streamlined. However, it also means that lesser offences within the same incident may not appear in the statistics, potentially underrepresenting the full scope of criminal activity. This rule is especially relevant when interpreting data on crimes like rape, where associated offences such as abduction or attempt to murder may be present but not separately tallied. Understanding this rule is crucial for researchers, policymakers, and advocates who rely on crime statistics to assess trends and design interventions.

Database B:

These are the database which used the data from NCRB in their reports:

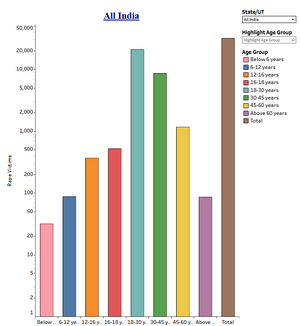

The bar graph specified above, from Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation[46] their sources being: Crime in India, National Crime Records Bureau, Ministry of Home Affairs; Women and Men in India, 2023[47], shows the rape occurrence across all the state in India across different Age Group.

The highest instance of rape is among the women aged between 18-30 years.

And, the lowest being the age below 6 years. This graph above shows Rape all over India for the year 2022.

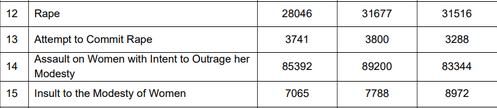

The Schedules below show the Official report of Crime Against Women in years

2020, 2021, and 2022. These Schedules were taken from GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. 1251 PDF[48]. Where there are questions asked regarding crime against women.

And, what question be held was: “(b) whether there has been highest increase in women abuse in the country especially in cases of rape and murder;”

Answers to this question were given with answers to question (a) and (c).

Those being, “(a) the number of cases which have been registered for Women abuse in the country, Statewise;” and, “(c) the number of accused persons have been convicted, acquitted for women abuse in the country during the last three years, State-wise;”.

The answer summarised: “The National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) publishes annual data on crimes reported by States/UTs in its Crime in India report, the latest being for 2022. Annexures provide state-wise details of cases registered under crimes against women (including rape and murder) from 2020–2022, along with data on convictions, acquittals, arrests, and disposals. The government attributes rising numbers partly to increased awareness of women’s rights, easier access to police (including Zero FIRs), gender-sensitivity training, and stricter action against erring officials, which have improved reporting mechanisms.” Or to look into the complete answers refer to the website cited.

BMC Public Health[49] has collected annual reports from the reports made by National Crimes Record Bureau (NCRB)[50]. Using this methods they have extracted the reports of Rape and other sexual offences committed against women and young girls.

The results were that there was an increase in all raped related crimes by 11.6% in 2001 to 19.8 in 2018 per 100,000 women and girls. It also said that most of the 70.7% of increase between the years 2001 to 2018, was after the 2012 gang rape and murder case, or the Nirbhaya Case. Most of the offences committed against women were, “recorded as assault with the intent to outrage modesty of the woman, followed by rape.”, - facts from the website.

The website also mentions that by the end of 2018, 9.6% of the cases had completed trials, with 73% of acquittal.

PMC or PubMed Central[51], and Hindustan Times[52] have used NCRB reports to come up with their reports or results too.

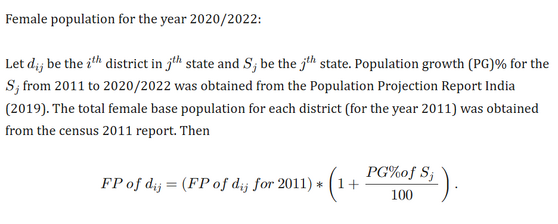

PubMed Central or PMC has used their formula to ascertain the district-wise female population, as the report only had information of state population, not district-wise. The

below formula was used with the explanation of the same with it:

This above image presents the creative notion of how research can be done using various forms, and using a formula is what PubMed Central has come up with.

Research that engages with the term ‘Rape’.

Research by “Indian Journal of Integrated Research in Law”[53]

There is a research on the term ‘Rape’ by Indian Journal of Integrated Research in Law says that rape is one of the most heinous crimes against humans, causing severe physical injuries and long-lasting psychological trauma. They also talk about how it undermines victims’ dignity, confidence, and sense of security, often devastating their very identity. In India, women from lower castes, minorities, and economically weaker sections are particularly vulnerable. They retort that slow legal process prolongs their suffering, highlighting the urgent need for prompt action and victim support.

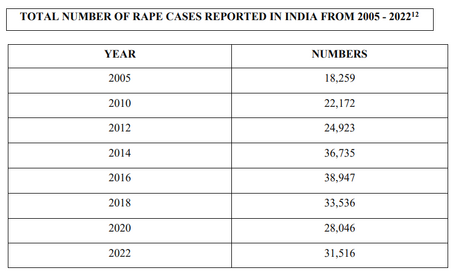

Indian Journal of Integrated Research in Law provides, taken report from NCRB, ‘Statistical Data on Sexual Violence in India’, and in the report they have produced data of rape cases that have been reported between year 2005 to 2022, it also says after 2012, yearly rape count recorded by the police was 25,000 across India, there was a general figure of 30,000 cases of rape apart from 2020 due to pandemic, but in year 2016 there was report of 39,000 rape cases.

And, in 2018, reports say, in average there was on e rape every 15 minutes. The latest report says, in the year 2022, there were reports of 31,000 cases.

This below Schedule shows the number of rape cases filed each year:

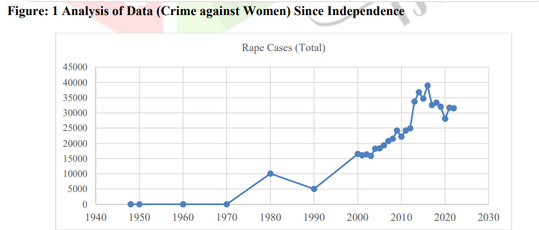

Research by “International Journal of Creative Research Thoughts (IJCRT)” [54]

This research provided by IJCRT gives us a line graph data of Rape cases since the time of Independence, nearly mid-1940s, this is the line graph they have provided:

Research by Tweisha Mishra[55] and Shantanu Pachauri[56]: “Developing a Uniform Sentencing Policy for Rape with Special Reference to the issue of Compromise[57].”

The research brings in light about the inconsistency in India’s sentencing for rape. The researcher argues that despite the offence being one of the gravest crimes of bodily autonomy and dignity, courts are often inconsistent with their judgements, as their judgements differ from case to case. The researcher criticizes this, as identical offenses yield in different sentences.

They dissect Indian rape law under the IPC, exposing its gaps and uneven judicial interpretation. A large portion of the study condemns the judiciary’s occasional acceptance of compromise settlements- where offenders and victims resolve the matter, often through social pressure, sometimes by marriage. The researchers are of the opinion that this compromise are both wrong and harmful as it makes rape seem like a small, personal issue between two people instead of recognizing it as a serious crime.

The researchers propose a uniform sentencing framework grounded in proportionality, consistency, and victim- centred justice. They argue that the punishment should reflect both the gravity of the act and the need for deterrence, not the personal circumstances or negotiations of the parties involved.

References that were used for the research were:

- D.A Thomas Principles of Sentencing.

- John Sir, Barry

- Ram V Adu, Mukna

- Karnataka V State Of, Krishnappa

The research concludes by suggesting that India must urgently codify sentencing policy for rape. First to eliminate arbitrary leniency, secondly forbidding compromise, and anchors judicial discretion in transparent guidelines. If we try to compress this research, it just conveys us that “uniformity of sentencing for a crime like rape is a backbone of the justice system”.

Research by Harshit[58]: “Legality of Compounding in Rape Cases

Part-I-The Unlawful Compromise.

Under Indian criminal law, rape is a non-compoundable offence and cannot be privately settled under Section 320 of the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC). Despite this, several High Courts and even the Supreme Court have, at times, allowed compromises or reduced sentences in rape cases by invoking their inherent powers under Section 482 CrPC, often citing “complete justice” or “exceptional circumstances.” This judicial trend has created serious confusion about whether such offences—being crimes against both the individual and society—can ever be resolved through private agreement.

A number of cases illustrate this inconsistent approach. In Baldev Singh v. State of Punjab (2011) and Ravindra v. State of Madhya Pradesh (2015), the Supreme Court reduced rape sentences because of delays and mutual settlements. Similarly, in Rahul v. State of NCT Delhi (2013) and Dalbir Singh v. State of Punjab (2015), courts treated marriage or compromise as grounds to reduce punishment or quash proceedings. The Madras High Court in V. Mohan (2014) even referred a rape case to mediation, while the Kerala High Court in Freddy (2018) and the Gauhati High Court in Md. Jahirul Maulana (2016) quashed rape cases after marriages between the accused and victim. The Supreme Court again followed this path in Saju P.R. v. State of Kerala (2019), quashing a rape case based on settlement.

These rulings, viewed as departures from settled law, have blurred the boundaries between private compromise and public justice. They raise critical concerns about whether compassion or social reconciliation should outweigh the fundamental legal principle that rape, as a grave violation of bodily autonomy and societal order, cannot be compounded under any circumstance.

Part-II-Removing the confusion

The law on rape in India treats the offence as heinous, non-compoundable, and a crime against society, not just the individual victim. The Supreme Court in the State of M.P. v. Bala made it clear that factors like delay in trial or an offer of marriage by the offender cannot justify leniency or compounding. The judgment reaffirmed that rape under Section 376 IPC is a grave violation of bodily integrity and human dignity, and that private settlements cannot override the need for justice and deterrence.

In Gian Singh v. State of Punjab, the Supreme Court distinguished between civil or personal disputes, which may be quashed on compromise, and serious offences such as rape, murder, or dacoity, which cannot be nullified through private agreements, even under Section 482 of the CrPC. Similarly, in Narinder Singh v. State of Punjab, the Court emphasized that crimes that harm society’s moral fabric must be prosecuted by the State, regardless of reconciliation between the parties. These rulings underline that rape is not a private dispute but a public wrong demanding punishment.

The judgment in Shimbhu & Anr. v. State of Haryana further stated that compromise or marriage with the accused can never be a reason for leniency. The Court warned that such compromises often result from social pressure or coercion and undermine the victim’s dignity. Likewise, in the State of M.P. v. Madan Lal, the Court declared that settlements in rape or attempted rape cases are legally impermissible, as these crimes strike at the core of a woman’s honour and societal values. The focus, therefore, must remain on justice and deterrence, not on reconciliation.

Reinforcing this position, later judgments such as State of T.N. v. R. Vasanthi Stanley and Ramphal v. State of Haryana clarified that while High Courts have inherent powers under Section 482 CrPC, they must not use these powers to quash rape cases based on compromise. In Ramphal, the Court went further to stress that instead of allowing settlements, courts should ensure victim compensation under Section 357(3) CrPC. Together, these rulings establish a consistent principle: rape is a crime against humanity and public morality, and cannot be compounded or diluted through private agreement.

Research by Sanjay Varshishtha: “Rape and Marriage Jurisprudence: A Study of Recent Judicial Trends Pertaining to Marriage Post Rape”[59].

The research explores the trouble in judicial practice of India where courts have increasingly treated marriage between a rape accused and the victim as a means of criminal proceedings. The research questions about women's rights, criminal justice, and the misuse of social morality within legal reasoning.

The researcher explores the judgment held by various high courts where marriage or a promise to marry was considered sufficient to grant bail or reduce criminal liability. Cases such as Chetan Chandrakant Tambatkar v. State of Maharashtra, Amarjeet v. State of U.P, and Monu v. State of U.P, are discussed in the research to illustrate how judicial discretion has often been taken away by social constructs of “honour” and “rehabilitation” rather than by legal principles.

The researcher argues that such decisions directly contradicts established Supreme Court ruling, which mentions rape as a heinous offence that can’t be nullified by private settlements. Further the research critiques the patriarchal nature of the judgments, which assumes that women’s dignity can be restored through marriage to her by the offender, thereby overlooking the trauma and lack of genuine consent that may accompany such arrangements.

The research concludes by asserting that the rape is not merely an offence against an individual but a grave offence against the entire society as a whole. He urges the judiciary to adopt a firm and consistent approach that upholds the rule of law, protects victim’s rights, and rejects marriage as a mitigating factor. Overall the essence of the research is just that true justice cannot coexist with the normalization of post rape marriages.

Challenges

There are several challenges that the Rape has in our nation, that is it does not recognise Rape done by husband on his wife, which is Marital Rape. The IPC and BNS have exempted Marital Rape in exception 2, unless, if the age of the wife is below 18.

According to Section 375 of the Indian Penal Code,1860 rape is defined as:

“penetrates his penis, to any extent, into the vagina, mouth, urethra or anus of a woman or makes her to do so with him or any other person”. And, consent must be not forcefully obtained, freely given, not coerced, presumption of such would not amount to consent, and also not by incapacity of the victim who can not freely or will-fully consent to such sexual intercourse. But, if a wife were to not consent to any form of sexual intercourse with the husband, and the husband proceeds to force the wife into it, Exception 2 under both IPC and BNS exempt it and not consider it as a Rape. A conundrum indeed. The Indian government has defended the marital rape exception, arguing that criminalizing marital rape could disrupt the institution of marriage and family structures. And, again, IPC and BNS, has only considered that rape can be done on and against female, exempting other genders from their interpretation of Rape. Sexual Offences faced by genders other than women are to be subjected to be not under Rape. This interpretation by the statutes are quite paradoxical.

The challenge in the term ‘rape’ also lies in its own definition as it differs from one jurisdiction to another or from one country to another, according to its relevant facts.

There can also be few modifications in respect of the definition of rape, as in, the judiciary can work upon to wider the scope of rape- including the cyber sexual assault and violence along with the act of penetration. Though the act of penetration is not present, it still has the same psychological impact on the victim. If the charges of the web-cam rape is considered as a rape then the very act of the man on a webcam can be reduced or minimised, as the fear of being convicted and trialled as an offender and then to be called as a rapist is a fear that men would procure from their reckless actions. This would let women explore the internet without ponder the fear of, or experiencing web-cam or digital rape.

Way Ahead

While we know that the laws of the land are always adopted for the best of the citizens, sometimes as the time passes by, there is a necessity to modify the law. For example- web-cam rape was not prevalent around 20th century because there wasn’t the required technology. But recently there has been a huge upsurge in this rape, but the constitution lacks the law for the same.

Along with this, efforts can be made to improve the procedure of rape, by streamlining investigation, educating the masses for reporting the crime, improving the trial procedures, to reduce unnecessary delays, victim’s insensitivity and to support victim effectively.

There have been retorts made by senior judges about marital rapes, as for in 2022, Justice Nagaprasanna of the Karnataka High Court rejected a plea invoking the marital rape exception, referencing the Justice J.S. Verma Committee's 2013 recommendation to remove the exception, and in a 2022 Delhi High Court split verdict, Justice Shakdher deemed the marital rape exception unconstitutional, arguing it violated a woman's bodily autonomy.

Contrastingly, Justice Shankar upheld the exception, asserting that sexual relations within marriage are a legitimate expectation, thus legitimizing the exception.

Shireen Jejeebhoy a prominent Indian social scientist specialising in population studies, Jejeebhoy has highlighted that marital violence is often perceived as acceptable behaviour in India's patriarchal setting, with the notion that marital rape is a husband's right deeply embedded in societal norms. And, in a 2025 study, Dr. Ghosh emphasized the urgency of criminalising marital rape in India, discussing its implications and the causes for its persistence within the existing legal framework.

Marital Rape, is a Rape, there was personal reasoning given up above in challenges section. There are experienced senior judges and prominent Indian social scientists who are against the exception mentioned in the statute. Yet, it still has not found its way out of the BNS. Interpretation of Rape has to be revised in our constitution, and it has to be very soon, if not so we will end up in the same circumstances, but with more cases, solved or unsolved in our hands.

Related terms

- Sexual Assault

- Sexual Abuse

- Sexual Violence

- Statutory Rape

- Assault by penetration

- Forcible Intercourse

- Molestation

- Sexual trafficking

- Stealthing

- Drug- facilitated sexual assault

Reference

- ↑ RAINN. (2025, October 9). Get the facts about sexual assault & rape

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 Ministry of Home Affairs. (2024). The Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023 (No. 45 of 2023)

- ↑ Bureau of Police Research and Development. (2024). Comparison summary: BNS to IPC

- ↑ Bureau of Police Research and Development. (2024). Comparison summary: BNSS to CrPC

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Lawgical HS30. (2024, April 5). Legality of compounding in rape cases Part I: The unlawful compromise

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Lawgical HS30. (2024, April 6). Legality of compounding in rape cases Part II: Removing the confusion

- ↑ Ministry of Home Affairs. (2022, December). Standard Operating Procedure for Investigation of Rape Cases

- ↑ Press Information Bureau. (2021, March 9). Women safety initiatives by Government of India

- ↑ https://www.google.com/search?q=ITSSO&oq=ITSSO&gs_lcrp=EgZjaHJvbWUyBggAEEUYOTIKCAEQABixAxiABDIKCAIQABixAxiABDIKCAMQABixAxiABDIKCAQQABixAxiABDIKCAUQABixAxiABDIHCAYQABiABDIKCAcQABixAxiABDIQCAgQABiDARixAxiABBiKBTIKCAkQABixAxiABNIBCDE5NTJqMGo3qAIAsAIA&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8

- ↑ Press Information Bureau. (2018, March 7). Government initiatives to ensure safety of women

- ↑ Republic of the Philippines v. R.P.B. (2019). Regional Trial Court Decision. Asian Development Bank Law and Policy Reform Database

- ↑ United Nations. (2021). Report of the Secretary-General on conflict-related sexual violence (A/75/826–S/2021/312)

- ↑ Bhubaneswar District Court. (2023). Circular No. 39 regarding rape case proceedings

- ↑ United Nations ESCWA. (2024). Marital rape – SDG glossary entry

- ↑ International Journal of Legal Literature and Research. (2024, October 15). Criminality of marital rape in India through the lens of Antonin Scalia and Arie Rosen

- ↑ Government of India. (2012). Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act, 2012 (No. 32 of 2012)

- ↑ Supreme Court Observer. (2025, January 20). Top court overturns Calcutta HC judgement that advised adolescent girls to control sexual urges

- ↑ HeinOnline. (2024). International Journal of Law and Legal Welfare, Vol. 11

- ↑ Gender Study Archive. (2024). Rameeza Bee: State complicity and gender violence

- ↑ United Nations ESCWA. (2024). Corrective rape – SDG glossary entry

- ↑ BBC News. (2024, June 21). The rape trial you didn’t see [Audio podcast episode]. BBC Sounds

- ↑ James Madison University Counseling Center. (2023). Acquaintance rape

- ↑ Shri Bodhisattwa Gautam v. Miss Subhra Chakraborty, AIR 1996 SC 722 (India)

- ↑ Peace Over Violence. (2025). Types of sexual violence

- ↑ Physicians for Human Rights. (2025, January). Kavuma case study: Toolkit on sexual violence documentation

- ↑ World Pulse. (2024). Types of rape you don’t know about

- ↑ BBC News. (2014, July 11). India rape laws: The problem with implementation

- ↑ Ghosh, A. (2024). Reframing rape discourse in India: Gender, law and justice. Journal of Gender Studies, 38(2), 1–18

- ↑ Supreme Court of India. (2025, January 20). Order in Criminal Appeal No. 36274/2022

- ↑ Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS). (2019). Ayahuasca community guide for the awareness of abuse

- ↑ State of Rajasthan v. Asharam Bapu, (2023). Rajasthan High Court Judgment

- ↑ Cornell Law School Legal Information Institute. (2024). Definition of rape under 34 U.S.C. § 343688665

- ↑ News Nation Now. (2024, September 18). “Rape club” in FCI Dublin prison: Former inmates share their stories

- ↑ Council of Europe. (1997). Rape and sexual violence: Report of the Committee on Equal Opportunities for Women and Men

- ↑ International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR). (1998). Prosecutor v. Jean-Paul Akayesu (ICTR-96-4-T)

- ↑ Government of India. (1860). Indian Penal Code (Act No. 45 of 1860)

- ↑ Department of Justice (Canada). (2024). Criminal Code, R.S.C. 1985, c. C-46, s. 271 (Sexual assault)

- ↑ Republic of South Africa. (2007). Criminal Law (Sexual Offences and Related Matters) Amendment Act 32 of 2007

- ↑ R v. R [1991] UKHL 12

- ↑ R v. Ewanchuk, [1999] 1 S.C.R. 330 (Can.)

- ↑ PGA v. The Queen, [2012] HCA 21 (Australia)

- ↑ Press Information Bureau. (2019, June 28). Government measures for safety and protection of women

- ↑ Times of India. (2025, February 20). Shakthi Teams emerge as a force in addressing crimes against women

- ↑ Press Information Bureau. (2025, March 8). Women safety initiatives under the Nirbhaya Fund

- ↑ National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB). (2023). Crime in India: 2022 Statistics

- ↑ Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MoSPI). (2023). State-wise and age-wise distribution of rape victims – 2022

- ↑ National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB). (2023). Crime in India portal

- ↑ Ministry of Home Affairs. (2025, February 11). Unstarred Question No. 1251 in Lok Sabha – Crimes against Women

- ↑ Mahapatra, R., & Das, S. (2022). Sexual violence in India: An epidemiological perspective. BMC Public Health, 22, 13182

- ↑ National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB). (2023). Crime in India: 2022 Statistics

- ↑ National Library of Medicine. (2024). Sexual violence reporting trends in South Asia. PLOS One, 19(3)

- ↑ Hindustan Times. (2023, December 27). Crimes against women and children rose by 4.87% in 2022: NCRB report

- ↑ International Journal of Indian Research Law. (2024, October). Combating rape in India: Analysing causes, legal provisions and recommendations

- ↑ International Journal of Creative Research Thoughts (IJCRT). (2025). Rape laws in India: A comparative study under BNS and IPC

- ↑ Social Science Research Network (SSRN). (2024). Author profile: ID 2700092

- ↑ Social Science Research Network (SSRN). (2024). Author profile: ID 4252078

- ↑ Gupta, N. (2021). Rape laws and societal response in India. SSRN Electronic Journal

- ↑ Lawgical HS30. (2024). Author profile

- ↑ SCC Online. (2022, November 5). Rape and marriage jurisprudence: A study of recent judicial trends pertaining to marriage post-rape