Search and seizure

What is search and seizure ?

Search and seizure refers to a law enforcement practice involving the examination of persons or places to collect evidence, apprehend suspects, or gather sufficient material to justify an arrest and secure a conviction[1]. The concept embodies a delicate balance within the justice system, where the need to maintain public order and enforce the law often comes into tension with the protection of individual rights[2]. The term "search" is rooted in the Old French word searcher, meaning “to follow, pursue, or inquire into,” which traces further back to the Latin secare, meaning “to cut” or “to divide.” This evolved into the modern sense of closely or thoroughly examining something. Similarly, "seizure" comes from the Old French seiser, and the Latin saisire, meaning “to take hold of,” now understood in legal contexts as the act of taking possession of property, often by force[3]. The extent of legal protection afforded to individuals during search and seizure processes varies across jurisdictions. In India, such actions may be conducted either with a warrant or, in specific circumstances, without one, depending on the legal authority and urgency involved.

Official definition

Despite not being explicitly defined in procedural or substantive acts, the process of search and seizure is governed by section 103 of the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023 . It explains the procedure of search and seizure and provides the duties of 'Persons in Charge During a Search'.

When a place that is subject to search or inspection is closed, the person residing in or responsible for it must, upon being shown a valid warrant, allow the officer access and assist in conducting the search[4]. If access is denied, the officer may force entry following the method outlined in Section 44(2)[5]. This includes breaking open outer or inner doors or windows of any building, whether it belongs to the person being arrested or someone else, if access is denied after the officer has clearly identified themselves, stated their purpose, and requested entry.

If there is reasonable suspicion that someone at the premises is hiding something on their body, that person may be searched. In the case of a woman, this search must be carried out by another woman, respecting decency[6]. Before beginning the search, the officer must call upon two or more respectable, independent individuals from the locality or nearby if none are available to witness the process[7]. These individuals may be officially ordered to participate. The search must be conducted in their presence, and a list of seized items and where they were found must be prepared and signed by the witnesses. However, witnesses are not required to attend court unless specifically summoned[8]. The occupant of the premises or someone on their behalf must be allowed to be present during the search, and a signed copy of the seizure list must be given to them[9]. If a person is searched, a list of items taken from them must also be prepared and a copy provided[10]. Refusing or neglecting to act as a witness to the search without reasonable cause, after receiving a written order, is punishable under Section 222 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023[11].

Search Warrants

A court can issue a search warrant if it reasonably believes that a person who has been summoned or asked to produce a document or item will not comply, or if the court does not know who currently holds the document or item, or if a general search would help the inquiry, trial, or proceeding[12]. The court may specify the exact place or part of a place to be searched, and the search must be limited to that area[13]. The power to issue warrants to search for documents or parcels held by postal authorities is on District Magistrate or CJM only[14].

If a District Magistrate, Sub-divisional Magistrate, or a Magistrate of the first class receives information and, after conducting any inquiry they consider necessary, believes that a location is being used to store or sell stolen goods or to keep or sell certain prohibited items, or that such prohibited items are kept there, they can issue a warrant. This warrant authorizes a police officer (above the rank of constable) to[15]:

- enter the premises, with help if needed;

- carry out a search as outlined in the warrant;

- take possession of anything found that they reasonably suspect to be stolen or prohibited;

- present such items before a Magistrate, secure them at the spot until the suspect is produced before a Magistrate, or keep them safely elsewhere;

- arrest and bring before a Magistrate any person found on the premises who appears to be involved in the storage, sale, or production of such items, knowing or reasonably suspecting them to be stolen or prohibited.

The prohibited or objectionable articles are[16] :

- counterfeit coins;

- metal items made illegally under the Coinage Act, 2011, or imported against customs regulations;

- counterfeit currency notes or stamps;

- forged documents;

- fake seals;

- obscene materials mentioned in Section 294 of the BNS

- tools or equipment used to produce any of the items listed above.

If the State Government believes a newspaper, book, or document contains material punishable by certain laws, it may declare all copies of that publication forfeited. Police officers may seize these copies, and magistrates can authorize searches for such material[17]. The definitions of “newspaper” and “book” follow the Press and Registration of Books Act, and “document” includes visible representations like paintings or photographs[18]. Actions or orders under this section can only be challenged through the procedure outlined in section 99[19]. A person interested in a forfeited publication may apply to the High Court within two months to revoke the forfeiture, arguing the publication did not contain the punishable material[20]. Applications are heard by a special bench of three or more judges, or all judges if fewer than three[21] and the Copies of the publication can be submitted as evidence regarding the nature of the content[22]. If the High Court finds the publication lacks punishable material, it will cancel the forfeiture[23].

If any District Magistrate, Sub-divisional Magistrate or Magistrate of the first class believes someone is wrongfully confined, they can issue a search warrant to locate that person. Upon finding the person, they must be immediately brought before the magistrate, who will decide on appropriate action[24].

Whenever a search is conducted or property is seized, the entire process must be recorded using audio-video electronic means, preferably on a mobile phone. This includes the making of the seizure list and getting it signed by the witnesses.The police officer must promptly send this recording to the District Magistrate, Sub-divisional Magistrate, or a Judicial Magistrate of the first class without delay.

Power of Police Officer to Seize Certain Property[25]

- A police officer has the authority to seize any property that is either suspected to be stolen or found in circumstances suggesting an offence might have occurred.

- If the police officer making the seizure is not in charge of the police station, he must immediately report the seizure to the officer in charge.

- Any police officer seizing property must report it to the Magistrate having jurisdiction. If the property: a) cannot be easily transported to the court, b) cannot be properly stored, c) or is not needed in police custody for investigation,

then the officer may hand over the property to a responsible person. That person must sign a bond promising to produce the property in court when required and comply with future court orders on its disposal. If the seized property is liable to quick decay, the rightful owner is unknown or absent, and its value is below ₹500, it may be sold by auction under the order of the Superintendent of Police. The rules in Sections 503 and 504 will apply to the proceeds of such sale, as far as practicable.

Attachment, Forfeiture or Restoration of Property[26]

- If during investigation a police officer reasonably believes that certain property is derived directly or indirectly from criminal activity or offence, they may apply to the Court or Magistrate handling the case after getting approval from the Superintendent or Commissioner of Police to have that property attached.

- If the Court or Magistrate, at any stage before or after hearing evidence, believes the property is indeed proceeds of crime, they will issue a notice to the person involved, asking them to explain within 14 days why the property should not be attached.

- If the property is held by another person on behalf of the accused, that person must also be served a copy of the notice.

- After considering any explanations and the evidence, and giving a fair hearing, the Court or Magistrate may order the attachment of the property if it is found to be proceeds of crime. If the person fails to respond or appear within 14 days, the Court may pass the order without their presence (ex parte).

- If the Court believes that giving notice might defeat the purpose of attachment, it may issue an interim ex parte order attaching or seizing the property, which remains effective until a final decision is made.

- If the Court confirms the property is proceeds of crime, it must order the District Magistrate to distribute the proceeds proportionally among those affected by the crime.

- The District Magistrate has 60 days to distribute the proceeds personally or through an authorized subordinate officer.

- If no claimants are found, or after claims are satisfied any surplus remains, the proceeds will be forfeited to the Government.

Any Magistrate authorized to issue a search warrant can also order that the search be conducted in their presence[27].

Search by Police Officer[28]

- The section empowers the officer in charge of a police station or any police officer conducting an investigation to search any place within the limits of their police station or jurisdiction. This power can be exercised when the officer reasonably believes that something necessary for the investigation may be found there, and that obtaining it by any other means would cause undue delay. Before conducting the search, the officer must record in writing the reasons for their belief in the case diary and specify, as far as possible, the item or thing to be searched for.

- The police officer carrying out the search should ideally conduct the search personally. Additionally, the entire search must be recorded using audio-video electronic means, preferably by mobile phone, to ensure transparency and accountability.

- If the officer in charge cannot personally conduct the search and there is no other competent person available at that time, the officer may write down the reasons for this and order a subordinate officer to conduct the search instead. This written order must specify the place to be searched and, as far as possible, the thing to be searched for. The subordinate officer is then authorized to carry out the search accordingly.

- The general provisions related to search warrants and other rules regarding searches stated in section 103 also apply to searches conducted under this section, to the extent possible. This ensures procedural consistency and legal safeguards.

- Copies of the written record of the search (made under subsections (1) or (3)) must be sent promptly, and in any case within 48 hours, to the nearest Magistrate who has the authority to take cognizance of the offence. Additionally, the owner or occupant of the searched place can apply to the Magistrate to receive a free copy of this record, ensuring transparency and the right to information for the affected parties.

Search and seizure in official documents and legislations

Kerala police Standard operating procedure

The Kerala Police SOP lays down specific procedures and guidelines to be observed during searches and seizures:

- Before entering the house, the Investigating Officer and witnesses should allow themselves to be searched by the occupant or a representative, who should be allowed to be present during the search.

- No person, except members of the household, should be permitted to enter or approach the house during the search.

- If necessary, female officers should accompany the search party, and their services can be arranged from the local police. Upon arrival, all telephones in the house should be secured by the search party.

- Members of the search party should behave politely with the inhabitants, especially women and elderly persons.

- Due respect should be shown to places of worship, but the search should still cover the entire premises.

- The search must be thorough and meticulous, ensuring that all incriminating documents and articles are seized in the presence of witnesses.

The Companies Act, 2013

The Companies Act, 2013 governs the formation, operation, and regulation of companies in India. It replaced the Companies Act of 1956, which was the first major corporate legislation enacted after independence, based on the recommendations of the Bhabha Committee. Over the years, the 1956 Act underwent numerous amendments, leading to the comprehensive overhaul in 2013. Section 209 under the Act, lays down the provisions related to search and seizure.

- If the Registrar or an inspector has reasonable grounds to believe—based on information received or otherwise—that the books and records of a company (or those of its key managerial personnel, directors, auditors, or practicing company secretary in the absence of an appointed CS) are at risk of being destroyed, tampered with, hidden, or falsified, they may, after obtaining permission from the Special Court, carry out the following:

- Enter and search the premises where such records are kept, with necessary assistance.

- Seize the relevant books and documents, allowing the company to take copies or extracts at its own expense.

- The seized documents must be returned within 180 days to the company from which they were taken. However, if required, the Registrar or inspector may retain them for an additional 180 days through a written order.

- Before returning the documents, the Registrar or inspector may:

- Take copies or extracts,

- Place identification marks on them,

- Or handle them in any other way considered necessary.

- The procedures for search and seizure outlined in the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 apply mutatis mutandis (i.e., with necessary changes) to actions taken under this section.

The Consumer Protection Act, 2019

The Consumer Protection Act, 2019 (CPA), first enacted in 1986 and revised in 2019, aims to protect consumers from unfair trade practices and ensure quick dispute resolution. Section 22 empowers the Director-General, an authorised officer, or the District Collector to investigate violations after a preliminary inquiry under Section 19(1). If they believe consumer rights have been violated, unfair trade practices committed, or false/misleading advertisements made, they may enter premises at a reasonable time to search for and seize relevant documents, records, or articles, make an inventory, or require any person to produce such items.

The procedures for search and seizure under the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 apply here. Seized or produced items must be returned within 20 days after certified copies or extracts are taken as prescribed. If items are perishable, they may be disposed of accordingly. For non-perishable articles, the provisions for analysis or testing in Section 38(2)(c) apply with necessary adjustments.

Judicial precedents

In K. Satwant Singh v. State of Punjab[29], the Supreme Court affirmed that the right against self-incrimination is a fundamental constitutional guarantee. The Court held that any statement obtained through coercion or inducement cannot be accepted as valid evidence. It further established that any search or seizure conducted in violation of an individual's right to due process would be deemed unlawful and inadmissible in court.

In M/S Bhumi Associate v. Union of India[30] , a division bench of the Gujarat High Court, in its order dated 18.02.2021, addressed complaints against tax authorities involving allegations of undue harassment, coercion, physical violence, and torture during search proceedings. The Court emphasized that tax officers and authorities “should act and perform their duties within the four corners of law.” While the officers are empowered to conduct search operations under Section 67 of the CGST Act, such actions must be “strictly in accordance with law.” This ruling underscores the settled principle that search and seizure powers granted under indirect tax statutes must be exercised within legal boundaries. However, when it comes to the Right to Privacy, especially in the context of such search procedures, the precise limits remain less clearly defined, creating an area of ongoing legal and constitutional debate.

In Shri Ramkishan Srikishan Jhever v. Commissioner of Commercial Taxes[31], a division bench of the Madras High Court examined the validity of search and seizure conducted without a warrant under the Madras Sales Tax Act, 1959. The Court acknowledged the complex balance between the fundamental rights of a citizen and the interests of the State, stating that “to what extent the fundamental right should yield to State necessity or public interest or to what extent the law should prevail over it is a question of nicety and difficulty which had to be resolved having regard to several factors.” The judgment recognized that effective law enforcement necessarily involves legally sanctioned interference with individual rights. While the Right to Privacy was argued as a ground to invalidate warrantless search and seizure, the Court rejected this contention, relying on precedents such as M.P. Sharma v. Union of India and similar cases, which upheld the legality of such searches within the framework of existing law.

In R. Manimaran v. State of Tamil Nadu[32], the Madras High Court held that vehicles seized under the NDPS Act cannot be released through CrPC provisions alone, even after acquittal. The appellant sought the return of a vehicle seized in 2021, but the Court ruled that disposal must follow the special procedure under Section 52A of the NDPS Act and the 2022 Drug Disposal Rules. Emphasizing that these provisions override Sections 451 and 452 CrPC, the Court noted that ownership and disposal decisions lie with the Drug Disposal Committee (DDC), not the trial court. It criticized the systemic neglect of timely disposal, which burdens courts and increases misuse risk. The judgment reinforces that disposal of seized vehicles must adhere strictly to the NDPS framework to ensure proper verification, prevent delays, and uphold the law’s integrity.

Research that engages with the topic

The article "Search and seizure of electronic devices in India: time for a change?" explores the lack of clear legal provisions in India for handling electronic device searches. It analyzes the Virendra Khanna v. State of Karnataka[33] judgment and contrasts India’s evolving legal position with the robust U.S. framework. It critiques missed opportunities in the 2023 data protection and criminal procedure bills and calls for reforms that uphold privacy while ensuring investigative efficiency[34].

The SFLC.in Guide on Search & Seizure of Electronic Devices, developed with UNESCO, offers a comprehensive overview of individuals' rights and responsibilities during the search and seizure of electronic devices in India. It explains legal safeguards under constitutional and statutory frameworks, outlines procedures to follow during and after a device seizure, and provides tips to secure digital privacy. It is particularly useful for journalists, activists, and citizens concerned with digital rights and law enforcement overreach[35].

In The Law of ‘Search and Seizure’ in India, Vijay Kumar Singh explores the multifaceted legal landscape of search and seizure provisions across Indian legislation. He emphasizes that while such powers are essential tools for law enforcement and regulatory authorities whether in criminal investigations, income tax raids, or proceedings under special laws like the IT Act and PMLA they must be exercised with strict adherence to legal procedures. Singh also cautions against arbitrary use, stressing the need for oversight and reporting to prevent violations of individual rights and ensure the admissibility of evidence[36].

The article “Right to Privacy in a Context of Search and Seizure” explores the significance of the right to privacy in India, identifying it as vital to individual dignity and freedom under the Constitution. It argues that privacy, while not absolute, must be legally justified when infringed. The piece compares U.S. protections under the Fourth Amendment, which require warrants and exclude unlawfully obtained evidence. It also highlights mechanisms like tort liability to check abuse of power. The discussion draws parallels between U.S. law and India's evolving stance under Article 21[37].

International experience

United States of America

The Fourth Amendment[38] of the U.S. Constitution safeguards individuals from unreasonable searches and seizures by the government. It mandates that warrants can only be issued upon probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and must specifically describe the place to be searched and the items to be seized. While it protects against unreasonable searches and seizures, it does not guarantee immunity from all such actions, only those deemed unreasonable under the law. Evidence obtained unlawfully typically cannot be used in criminal proceedings, underscoring the requirement that government intrusion into areas of reasonable privacy must be justified. In United States v. Jacobsen[39], the Supreme Court clarified that the Fourth Amendment: "protects two types of expectations: one related to 'searches,' where there is an infringement on a reasonable expectation of privacy; and another related to 'seizures' of property, which occurs when there is a meaningful interference with an individual's possessory interests in that property."

New Zealand

In New Zealand, the Search and Surveillance Act 2012 aims to modernize laws governing search, seizure, and surveillance, adapting to technological advancements while upholding human rights values. It facilitates monitoring of legal compliance and enhances investigation and prosecution capabilities. Part 2 of the Act delineates various powers related to search and surveillance. Section 334 of the Resource Management Act 1991 states that “entry to search can be sought if there are reasonable grounds to believe that an offense punishable by imprisonment has occurred”. These warrants authorize searches for specific items believed to be located in any place or vehicle, intended to provide evidence of or related to the offense. Additionally, section 21 of the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990 mandates that any search or seizure conducted under a public function must be reasonable. Violations of this requirement may result in legal actions and potential compensation for damages.

Data on search and seizure

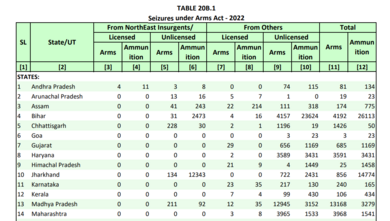

The Crime in India 2022 report (Volume 3) by the NCRB provides detailed data on seizures and prosecutions conducted by State/UT police, Central Armed Police Forces, and Central Law Enforcement Agencies, including statistics on arms, currency (both original and counterfeit), narcotics, explosives, and other contraband across multiple chapters.For further details and additional data, refer to Chapters 20B, 20C, and 20D of the report,

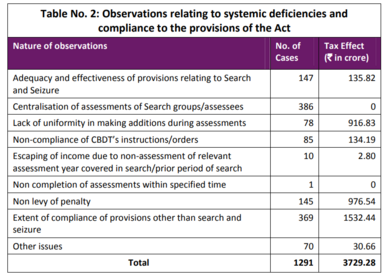

The Report of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India for the year ended March 2019 presents a performance audit on Search and Seizure Assessments conducted by the Income Tax Department. Prepared for submission to the President under Article 151 of the Constitution, the report covers significant findings from audits carried out between 2014-15 and 2017-18 within the Department of Revenue – Direct Taxes. The audit, conducted from March to July 2019 in accordance with CAG auditing standards, highlights key instances that came to light during the examination[40].

References

- ↑ Fourth Amendment, Encyclopaedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Fourth-Amendment (last visited May 22, 2025)

- ↑ Search and Seizure and the Bill of Rights, EBSCO Research Starters, https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/law/search-and-seizure-and-bill-rights (last visited May 22, 2025)

- ↑ Seizure, Online Etymology Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/word/seizure (last visited May 22, 2025).

- ↑ S 103 (1) of BNSS

- ↑ S 103 (2) of BNSS

- ↑ S 103 (3) of BNSS

- ↑ S 103 (4) of BNSS

- ↑ S 103 (5) of BNSS

- ↑ S 103 (6) of BNSS

- ↑ S 103 (7) of BNSS

- ↑ S 103 (8) of BNSS

- ↑ S 96 (1) of BNSS

- ↑ S 96 (2) of BNSS

- ↑ S 96 (3) of BNSS

- ↑ S 97 ( 1) of BNSS

- ↑ S 97 (2) of BNSS

- ↑ S 98 (1) of BNSS

- ↑ S 98 (2) of BNSS

- ↑ S 98 (3) of BNSS

- ↑ S 99 (1) of BNSS

- ↑ S 99 (2) of BNSS

- ↑ S 99 (3) of BNSS

- ↑ S 99 (4) of BNSS

- ↑ S 100 of BNSS

- ↑ S. 106 of BNSS

- ↑ S 107 of BNSS

- ↑ S 108 of BNSS

- ↑ S. 185 of BNSS

- ↑ AIR 1960 SC 266

- ↑ 2021 (2) TMI 701

- ↑ 1965 16 STC 708 (Mad)

- ↑ Crl.A.(MD) No.192 of 2024

- ↑ AIRONLINE 2021 KAR 525

- ↑ Shah, M. G., Gupta, A., & Bajpai, A. (2024). Search and seizure of electronic devices in India: time for a change? The International Journal of Evidence & Proof, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/13657127241230694

- ↑ Software Freedom Law Center, India, Guide: Search and Seizure of Electronic Devices, SFLC.in (Feb. 25, 2025), https://sflc.in/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/SFLC.IN-GUIDE-SEARCH-AND-SEIZURE-OF-ELECTRONIC-DEVICES-1.pdf

- ↑ Singh, Vijay Kumar, Law of Search and Seizure in India (2009). Chapter in edited book on Law of Search and Seizure, Amicus Books, ISBN: 978-93-80120-06-5, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2972055 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2972055

- ↑ Right to Privacy in a Context of Search and Seizure, Indian Journal of Law, Polity and Administration, ISSN: 2582-7677, at 16 (2021), available at https://www.ijlpa.com/_files/ugd/006c7e_ec0ed656e5e44cccbeb86e3eb171e4f4.pdf

- ↑ U.S. Const. amend. IV.

- ↑ 466 U.S. 109, 113 - 14 (1984).

- ↑ Comptroller & Auditor Gen. of India, Performance Audit on Search and Seizure Assessments in Income Tax Department, Report No. 11 of 2019, for the year ended Mar. 2019, available at https://cag.gov.in (last visited May 20, 2025).