Sedition

What is Sedition

Sedition is a form of speech and expression intended to incite insurrection against the governing authority. Edward Jenks, in The Book of English Law, contends that sedition is “perhaps the very vaguest of all offences”.[1]Sedition is the conduct or language inciting rebellion against the constituted authority in a state.[2] Another alternate definition states that it is in speech, writing, or behavior intended to encourage people to fight against or oppose the government.[3]

'Sedition' has been defined in “Black's Law Dictionary[4] as:

- An agreement, communication, or other preliminary activity aimed at inciting treason or some lesser commotion against public authority.

- Advocacy aimed at inciting or producing – and likely to incite or produce- imminent lawless action. At common law, sedition included defaming a member of the royal family or the government. The difference between sedition and treason is that the former is committed by preliminary steps, while the latter entails some overt act for carrying out the plan. But if the plan is merely for some small commotion, even accomplishing the plan does not amount to treason.”

Official definition of Sedition

Sedition as defined in Legislations

Sedition was defined explicitly in the Section 124A of the erstwhile Indian Penal Code,1860[5] but is not explicitly mentioned in Bhartiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023. Section 152 of the Bhartiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS), 2023[6] seeks to criminalise ‘Acts endangering sovereignty, unity and integrity of India’ and punishes them with imprisonment for life or with imprisonment which may extend to seven years and fine. The minimum punishment for the offence has been increased from three years to seven years.

Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) and Indian Penal Code (IPC)

Section 124A of IPC[7] define Sedition as:-

Whoever by words, either spoken or written, or by signs, or by visible representation, or otherwise, brings or attempts to bring into hatred or contempt, or excites or attempts to excite disaffection towards the Government established by law in shall be punished with imprisonment for life, to which fine may be added, or with imprisonment which may extend to three years, to which fine may be added, or with fine.

Explanation 1.—The expression “disaffection” includes disloyalty and all feelings of enmity.

Explanation 2.—Comments expressing disapprobation of the measures of the Government with a view to obtain their alteration by lawful means, without exciting or attempting to excite hatred, contempt or disaffection, do not constitute an offence under this section.

Explanation 3.—Comments expressing disapprobation of the administrative or other action of the Government without exciting or attempting to excite hatred, contempt or disaffection, do not constitute an offence under this section.

Broadly, the essentials of Sedition can be seen as:-

- Presence of Intention or knowledge

- excites or attempts to excite, secession or armed rebellion or subversive activities, or encourages feelings of separatist activities or endangers sovereignty or unity and integrity of India; or indulges in or commits any such act

- Through words, either spoken or written, or by signs, or by visible representation, or otherwise[8]

Modifications under Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita

Section 152 of the Bhartiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS), 2023 is in the same vein as s. 124A of the IPC.[6] The provision may not be labelled ‘sedition’, but the spirit of that provision has been retained and potentially, covers a wider range of acts which themselves suffer from ambiguity and vagueness in their current form, creating implications for its constitutionality. The IPC requires exciting disaffection, hatred or contempt towards ‘the Government established by law in India’, whereas Section 152 of BNS mentions endangering the ‘sovereignty, or unity and integrity of India’. The former lends itself to conceptualising the government as an identified and separate entity whereas the latter expands the scope of offence because the nation is a necessarily abstract concept and does not lend itself to specificity. [9]

- ‘Sedition’ has been replaced by a new offence, defined in section 152 of the BNS, titled ‘Act endangering sovereignty, unity and integrity of India’ and differs in some ways from its counterpart in the IPC. While the word ‘sedition’ has been removed from the penal statute, the new provision appears to be as rights-restrictive as its counterpart.

- Section 124A of the IPC focuses on activities that excite hatred, contempt or disaffection towards the government, whereas Section 152 of the BNS penalises activities that excite ‘subversive activities’ or encourage ‘feelings of separatist activities’ or endanger the ‘sovereignty or unity and integrity of India.’ The BNS does not explain what constitutes exciting ‘subversive activities’ or encouraging ‘feelings of separatist activities’.

Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS) 2023

Section 127 of the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS) 2023[10] deals with securing good behavior from individuals who disseminate certain matters. Specifically, it addresses situations where a person disseminates seditious matters or matters that constitute criminal intimidation or defamation of a judge, or disseminates obscene materials. The Magistrate may require such individuals to show cause why they should not be ordered to execute a bond for good behavior for a period not exceeding one year.

It may also be noted that s. 108 of the CrPC which provides for obtaining security for good behaviour from persons disseminating 'seditious matters' has been substantially retained in Section 127 of the BNSS which changes the terminology from 'seditious matter' to 'certain matters'.

Sedition as defined in official government reports

Law Commission Report

- The 42nd Report of the Law Commission[11] termed the punishment for Section l24Ato be very 'odd'. It could be either imprisonment for life or imprisonment up to three years only, but nothing in between, with the minimum punishment being only fine. A comparison of the sentences as provided for the offences in Chapter VI ofthe IPC suggests that there is a glaring disparity in the punishment prescribed for Section 124A. It is, therefore, suggested that the provision be revised to bring it in consonance with the scheme of punishment provided for other offences under Chapter VI. This would allow the Courts greater room to award punishment for a case of sedition in accordance with the scale and gravity of the act.

- The 279th Report of the Law Commission of India[12] delved deep into the issue of Sedition, considering the history, evolution, case judgements and the way forward on this law. The Commission found it ‘imperative’ to retain sedition laws because threats to internal security are inextricably linked to the sovereignty of the country. It also laid a condition that sedition will apply when there is a ‘tendency to incite violence or cause public disorder'. three major recommendations were given by the commission. Firstly, it recommended widened the scope of sedition; Second, adding a higher quantum of punishment, and third, incorporating ‘procedural safeguards’ to prevent misuse. It also highlighted certain issues that need to be addressed:

- The definition of sedition is that it does not take into account disaffection towards (a) the Constitution, (b) the Legislature, and (c) the administration of justice, all of which would be as disastrous to the security of the State as disaffection towards the executive Government.

- The LCI’s proposed amendments also include an enhanced punishment for sedition. Section 124A currently provides for life imprisonment, or imprisonment up to three years and/or fine. The LCI proposes to increase the three years to seven years.

- The recommendation also creates another condition for attracting Section 124A – ‘tendency to incite violence’. This phrase is defined as ‘mere inclination to incite violence or cause public disorder rather than proof of actual violence or imminent threat to violence’. This is a very low threshold and becomes a matter of interpretation, not only on what acts ‘tend to incite violence’, but also on what would constitute a disturbance of public order, which is not only subjective, but also not settled in Indian free speech jurisprudence. [13]

Sedition as defined in case laws

Post-independence, courts have had multiple occasions to interpret Section 124A of the IPC, particularly regarding its impact on the right to freedom of speech guaranteed under the Constitution. These decisions have had the effect of limiting the scope of the section to only curb speech that poses an imminent threat to public order. In this light, the scope of Section 152 of the BNS—a completely new provision with changed standards—is unclear since the tests evolved by the courts in decisions regarding Section 124A of the IPC no longer apply.

Romesh Thappar vs The State of Madras,1 950

The drafters of Indian constitution excluded the word ‘sedition’ from the constitution and retained it under penal laws post-independence. The first case for validity of s.124A IPC came before the courts in Romesh Thapar case.[14] The Supreme Court observed that any provision restricting free speech and expression cannot be a part of Article 19(2) unless it is a threat to State security. The after effect of the case was that it led to the constitutional amendment. And the terms “public order” and “relations with friendly states” were included as exceptions in the Indian Constitution's First Amendment, and the word “reasonable” was added prior to “restrictions.”

Later, section 124A IPC was held unconstitutional in Tara Singh v. The State of Punjab[15] case. Also, In the Ram Nandan’s[16] Case, section 124A was challenged and this section pertaining to sedition law was held as unconstitutional.

Kedar Nath Das v. State of Bihar, 1967

Kedar Nath was a member of the Forward Communists Party of Bihar charged with sedition for accusing Congress of corruption and attempts to redistribute land at a speech in Barauni in 1953. A five-judge bench of the Supreme Court in the Kedar Nath's case[17], headed by Chief Justice B.P. Sinha, upheld provisions in the Indian Penal Code criminalizing sedition. The law remained punishable with imprisonment up to a life sentence. However, the court specified that sedition can only be charged if the expression in question involves “intention or tendency to create disorder, or disturbance of law and order; or incitement to violence.” Sinha offered the opinion that the law should solely be applied in cases that “ameliorate the condition of the people.” This shift in emphasis to the incitement of violence warranting a sedition charge has popularized the law’s use against grassroots organizers, social media influencers, and journalists. What acts constitute “violence” or “disorder” is subjective to the opinions of officials in power. The Supreme Court further justified their decision by quoting Article 19 (2) of the Indian Constitution in their opinion, which states “reasonable restriction” can be placed by the government on freedom of speech and expression.

Balwant Singh v. State of Punjab, 1995

In Balwant Singh v State of Punjab,1995[18] the Supreme Court held that merely raising slogans without any other action that incites violence did not amount to sedition. The case led to the inclusion of an ‘intent test’, which excluded from the scope of sedition acts of criticism without malicious intent. Therefore, while the provision on sedition was retained in the statute book, it underwent certain developments with a positive impact on the right to free speech.

S.G Vombatkere v. Union of India, 2022

In S.G Vombatkere v. Union of India[19] the constitutionality of section 124A IPC was again challenged before the Supreme Court of India. However, the Court ordered that the law be kept in abeyance, and no First Information Report (‘FIR’) be registered by Central or State Governments. An FIR is a document prepared by the police on basis of a complaint received by them, which has information about the alleged crime. It is followed by investigation and sets the criminal justice system in motion. The Court also ordered that trials pending under the sedition law should only be continued if they do not cause any prejudice towards the accused. This order came after the Government filed an affidavit in which it stated that the sedition law would be ‘re-examined’.

Appearance of Sedition in databases

Crime in India Report

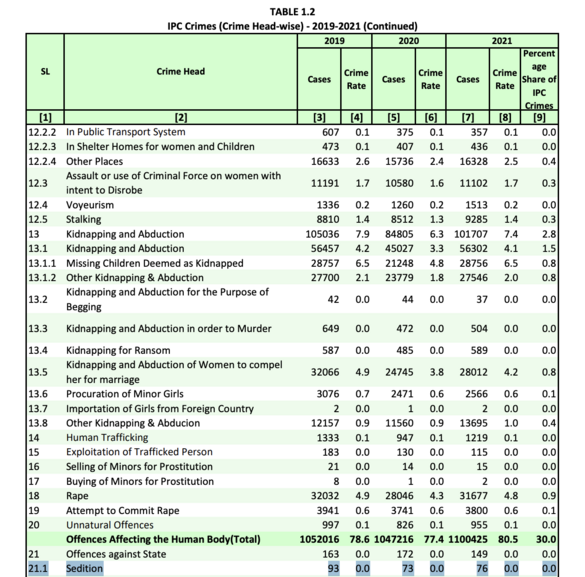

The Crime in India Report (NCRB)[20] compiles and publishes crime statistics as reported by states and Union Territories, and data on sedition cases (registered under Section 124A of the IPC). NCRB began documenting sedition cases only in 2014.

The data on sedition cases is given under the headline ‘Offences Against State’. While cases registered under the Section 124A of the IPC have been mentioned under the sub-head ‘Sedition’, the cases registered under Section 121, 121A, 122 and 123 IPC have been given under the second sub-head ‘Others’.

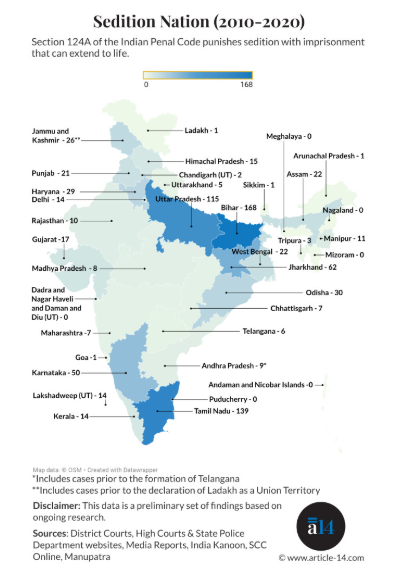

Decade of Darkness (Article 14)

This dynamic database contains information on all cases of sedition filed in India from 1 January 2010 onwards.[21] All cases implicate Section 124A of the Indian Penal code. The data is sourced from a combination of open access, subscription based platforms and investigative reporting. Data mining was carried out across national & regional digital media, the E-Courts portal, Indian Kanoon, State Police Department websites and subscription based platforms like SCC Online and Manupatra. The investigative reporters also interviewed more than 70 persons accused of sedition.

Research that engages with Sedition

Sedition law and death of free speech (Alternate law forum)

The research report by Centre for the study of social Exclusion and Inclusive Policy, National Law School of India Policy, Bangalore & Alternate Law Forum titled Sedition law and death of free speech published in February 2011, brings together various arguments to make the case for a repeal of these laws.[22] It critics section 124A IPC as inherently colonial and draconian. It is not used to protect national security rather to suppress dissent and curbs democratic rights, such as free speech, protest and freedom of press. UK government abolished sedition in 2009 but India retains it and the law essentially contradicts with constitutional rights like Article 19(1)(a) that guarantees freedom of speech and Article 19(2) that allows reasonable restriction on speech and expression. However, sedition law puts unreasonable restriction on such rights. The report also provides case studies showing the misuse of sedition to suppress dissent and target young activists.

The research gives data from NCRB that shows the rise of sedition cases however, the rate of conviction remains considerably low. The Courts have failed to check executive overreach, where Government purposely use sedition to silence criticism of its policies and control the narrative. The research recommends for the complete repeal of section 124A IPC to uphold constitutional protection of fundamental rights such as free speech and peaceful dissent.[23] It also called for police and prosecutorial accountability for misuse of laws and to educate citizens and institutions about the constitutional value of dissent in a democracy and safeguarding the rights of young activists and students.

References

- ↑ 'Edward Jenks', The Book of English Law 136 (P.B. Fairest ed., 6th ed. 1967). https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/sedition

- ↑ Sedition, Oxford English Dictionary.https://www.oed.com/dictionary/sedition_n

- ↑ Sedition, Collins English Dictionary, https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/sedition

- ↑ p.1479 Black's Law Dictionary” (Ninth Edition) available at: https://archive.org/details/blacks-law-9th-edition/page/n9/mode/2up

- ↑ Section 124A, Indian Penal Code, 1860 (repealed). https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?actid=AC_CEN_5_23_00037_186045_1523266765688&orderno=133

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, § 152 (2023) (India). https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?abv=CEN&statehandle=123456789/1362&actid=AC_CEN_5_23_00048_2023-45_1719292564123§ionId=90517§ionno=152&orderno=152&orgactid=AC_CEN_5_23_00048_2023-45_1719292564123

- ↑ Indian Penal Code, § 124A (1860) (India). https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1641007/

- ↑ John D. Smith, Reforming Sedition Laws in India, 11 Ind. J. L. & Legal Stud. 400, 412 (Year), https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/injlolw11&div=392&id=&page=

- ↑ https://p39ablog.com/2023/09/criminal-law-bills-2023-decoded-8-sedition-recast-implications-of-clause-150-of-the-bns-2023/

- ↑ Bharatiya Nagarika Suraksha Sanhita, § 127 (2023) (India). https://indiankanoon.org/doc/153742946/

- ↑ Law Com’n of India, One Hundred Fifty-Sixth Report on the Indian Penal Code (Amendment), Including Proposed Community Service as a Punishment 67 (1997). https://cdnbbsr.s3waas.gov.in/s3ca0daec69b5adc880fb464895726dbdf/uploads/2022/08/2022081040.pdf

- ↑ Law Com’n of India, Report No. 279: Usage of the Law of Sedition (Apr. 2023), https://cdnbbsr.s3waas.gov.in/s3ca0daec69b5adc880fb464895726dbdf/uploads/2023/06/2023060150.pdf

- ↑ Mohammad Zayaan, Worrying Recommendations on Reform of Sedition Law from the Law Commission of India, Oxford Human Rights Hub (Jul. 19, 2023),https://ohrh.law.ox.ac.uk/worrying-recommendations-on-reform-of-sedition-law-from-the-law-commission-of-india/

- ↑ Romesh Thappar vs The State Of Madras 1950 SCR 594, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/456839/

- ↑ Tara Singh v. State of Punjab, AIR 1951 SC 441 (India). https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1912825/

- ↑ Ram Nandan v. State, AIR 1959 All. 101 (India). https://indiankanoon.org/doc/537326/

- ↑ Kedar Nath Singh v. State of Bihar, AIR 1962 SC 955 (India). https://indiankanoon.org/doc/111867/

- ↑ Balwant Singh & Anr. v. State of Punjab, (1995) 3 SCC 709 (India). https://indiankanoon.org/doc/123425906/

- ↑ S.G. Vombatkere v. Union of India, MANU/SCOR/45878/2022 (India).https://indiankanoon.org/doc/134384639/

- ↑ Nat’l Crime Rcds. Bureau, Crime in India 2021: Volume 1 – Statistics (Ministry of Home Affairs, Govt. of India 2022), https://www.ncrb.gov.in/uploads/nationalcrimerecordsbureau/custom/1696831798CII2021Volume1.pdf

- ↑ A Decade of Darkness: India’s Sedition Database (2010–2021), Article 14 (Feb. 4, 2022), https://sedition.article-14.com/#

- ↑ Centre for Study of Social Exclusion and Inclusive Policy & Alternative Law Forum, Bangalore, Sedition Laws & the Death of Free Speech in India (2011), https://altlawforum.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Sedition-Laws-the-Death-of-Free-Speech-in-India.pdf

- ↑ Jwalika Balaji & Aditya Prasanna Bhattacharya, The Problem With Section 152, Times of India (May 22, 2025, updated May 22, 2025, 21:24 IST),https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/toi-plus/law/the-problem-with-section-152/articleshow/121344431.cms