Terrorist Act

What are Terrorist Acts?

Terrorism is the deliberate use of violence to instill fear within a population, with the aim of achieving a specific political objective, often resorting to increasingly dramatic, violent, and high-profile attacks, including hijackings, hostage situations, kidnappings, mass shootings, car bombings, and suicide bombings[1].The underlying causes of terrorism and insurgency in India are rooted in political, religious, ethnic, ideological, identity-driven, linguistic, or socio-economic grievances. In many cases, religious groups also serve as tools for indoctrination and radicalization, influencing individuals, including not only the poor and marginalized but also those from diverse backgrounds, to engage in extreme violence and terrorism[2].

The official definition in legislations

Terrorist and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act, 1987

TADA is one of the first laws enacted to deal with terrorism in India. It was introduced in 1985, shortly after the assassination of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, during a time of growing unrest. The law remained in force till 1995, after which it lapsed, following widespread allegations of misuse. In this act terrorist act is defined in Section 3 (1) as

An act done with the intent to:

- Overawe (intimidate) the Government as established by law,

- Strike terror among the people or any section of the people,

- Alienate any section of the people, or

- Adversely affect harmony among different sections of the people.

The act must involve the use of bombs, dynamite, or other explosive substances, inflammable substances, lethal weapons, poisons or noxious gases or other chemicals, or any other substances (biological or otherwise) of a hazardous nature. It must be done in such a manner that it causes or is likely to cause death or injuries to any person(s), loss, damage, or destruction of property, disruption of supplies or services essential to the life of the community. Although the TADA was repealed, the definition provided therein has formed the basis for subsequent legislation.

The Prevention of Terrorism Act, 2002

Following the 2001 attack on the Indian Parliament, POTA was passed to strengthen the country's legal response to terrorism. However, the law quickly drew heavy criticism for enabling widespread human rights violations. POTA's broad definition of a ‘terrorist act’ extended even to political dissent, allowed for extended pre-trial detention, and shifted the burden of proof onto the accused by reversing the presumption of innocence. Due to these concerns, the Act was repealed in 2004. Nevertheless, POTA remains significant today, as its repeal did not impact ongoing investigations and legal proceedings initiated under its framework[3].

Section 3 (1) of POTA defines terrorist acts. Compared to the earlier definition under TADA, the definition of a terrorist act in POTA, 2002 added several new elements. It expanded the scope by explicitly mentioning threats to the unity, integrity, security, and sovereignty of India. It allowed for broader methods of committing terrorist acts by including the phrase "any other means whatsoever," not limiting it to specific weapons like bombs or firearms. POTA also included the destruction or damage of defense-related property or government facilities as part of terrorist acts. Additionally, it brought in provisions where being a member of an unlawful association under the UAPA while possessing illegal arms and causing harm, would be treated as committing a terrorist act. Lastly, the act of raising funds for terrorism was specifically recognized as a terrorist act, which was not explicitly mentioned under TADA.

The Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967

UAPA is currently India's main anti-terrorism law. Originally passed by Parliament in 1967, its purpose was to allow reasonable restrictions on the rights to free speech, peaceful assembly, and the formation of associations, specifically to protect India's sovereignty and integrity. At the time of its enactment, the Act mainly targeted general unlawful activities, without focusing on terrorism. Provisions specifically addressing terrorism were introduced later, starting with major amendments in 2004 after the repeal of POTA. The UAPA was further strengthened in 2008 following the Mumbai terrorist attacks, with the addition of Section 15 defining a ‘terrorist act’ and the creation of new terrorism-related offences. Currently, section 15(1) reads:

A person commits a terrorist act if they perform any action with the intent or likelihood of threatening the unity, integrity, security, economic stability, or sovereignty of India, or to instill terror among the people in India or abroad. This includes:

- Using bombs, explosives, inflammable substances, firearms, lethal weapons, poisonous gases, radioactive, nuclear, biological, or other hazardous materials, or any other means to[4]:

- Cause death or injuries to individuals[5],

- Damage, destroy, or cause loss to property[6],

- Disrupt supplies or services essential to community life in India or any foreign country[7],

- Harm India's monetary stability through the production, smuggling, or circulation of high-quality counterfeit currency or related materials[8],

- Damage or destroy property used for defense purposes or government functions in India or abroad[9].

- Using criminal force or threatening to do so to intimidate public officials, or attempting or causing the death of public functionaries[10].

- Detaining, kidnapping, or abducting any person with threats of harm, to pressure the Indian government, a state government, foreign governments, international organizations, or individuals into taking or refraining from certain actions[11].

The First Schedule of the UAPA lists terrorist organizations, which the Central Government can modify[12]. Mere membership in such a terrorist group is considered an offense under the Act. A person who associates with or claims to be associated with a terrorist organization, with the intention to promote its activities, is guilty of the offense of "membership of a terrorist organization" and can face up to ten years of imprisonment, a fine, or both[13]. Additionally, providing support to a terrorist organization through funds, property, arranging meetings to promote its activities, addressing meetings to encourage support[14], or raising funds for such a group[15] are also offenses under the UAPA.

The Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023 ('BNS')

The BNS came into effect on July 1, 2024, replacing the Indian Penal Code,1860. Compared to the old penal law, the new code includes provisions related to terrorist acts and organized crime under the chapter on offences affecting the human body. In contrast, terrorism laws were typically categorized under offences against the state in the previous framework. The UAPA focuses on acts aimed at "striking terror," while the BNS broadens this scope to include acts intended to intimidate the public or disturb public order. This makes the general law's definition more expansive than that of the special law, potentially covering a wider range of activities. However, the procedural safeguards provided in the UAPA for terrorist acts have not been incorporated into the BNS[16].

Section 113 of the BNS provides that

A terrorist act is committed when an individual, in India or abroad, intentionally threatens the unity, integrity, and security of India, intimidates the public, or disrupts public order through any violent means including[17]

- Using bombs, explosives, inflammable substances, firearms, lethal weapons, poisonous gases, hazardous chemicals (biological, radioactive, nuclear, etc.), or any other means to cause or likely to cause[18]:

- death or injury to any person[19];

- loss, damage, or destruction of property[20];

- disruption of essential supplies or services in India or abroad[21];

- harm to India's monetary stability through counterfeit currency, coins, or materials[22];

- damage or destruction of property used for India's defence or government purposes[23].

- Overawing or attempting to overawe by criminal force, or causing or attempting to cause death of any public functionary[24].

- Detaining, kidnapping, or abducting a person to threaten, kill, injure, or compel the Government of India, any State Government, foreign government, international body, or any person to act or refrain from acting[25].

Anyone who attempts or commits a terrorist act faces severe penalties. If the act results in the death of a person, the offender shall be punished with either the death penalty or life imprisonment without the possibility of parole, along with a mandatory fine[26]. In all other cases, the punishment includes a minimum imprisonment of five years, which may extend to life imprisonment, accompanied by a fine[27].

Anyone who conspires, organizes, or facilitates the formation of any organization[28], association, or group for carrying out terrorist acts, or aids in preparatory activities[29] for such acts, shall face a minimum imprisonment of five years, extendable to life imprisonment, along with a fine. Any individual who is a member of a terrorist organization involved in terrorist activities shall be subject to imprisonment, which may extend to life, and a fine[30].

Anyone who intentionally harbors, conceals, or attempts to protect a person involved in a terrorist act shall face imprisonment ranging from a minimum of three years to life imprisonment, along with a mandatory fine. However, this provision does not apply if the act of harboring or concealment is carried out by the offender's spouse[31].

Anyone who directly or indirectly possesses, acquires, provides, collects, or utilizes property or funds derived from terrorist activities or obtained through terrorist financing, or offers financial or related services to support terrorist acts, shall face imprisonment of up to life and a mandatory fine of no less than five lakh rupees. Additionally, any such property shall be subject to attachment and forfeiture[32].

Legal provisions relating to Terrorist Acts

The National Investigation Agency Act, 2008

Terror-related activities, including the use of bombs, dynamite, poisons, various gases, and biological, radioactive, and nuclear substances, have been specifically addressed in the NIA Act[33], which was enacted to establish the NIA as the primary counter-terrorism law enforcement agency in India. The introduction of the NIA was necessitated by the increasing frequency and complexity of terrorist attacks in India, many of which had inter-state and international linkages. The Act empowers the NIA to investigate and prosecute offences related to terrorism and other threats to national security under various designated laws. Even though the NIA can act suo motu to deal with terrorism, the Act grants states the authority to alert the NIA when they discover offences related to terrorism being committed.

Key provisions of the Act include the establishment of Special Courts for the speedy trial of terrorism cases, concurrent jurisdiction allowing both the NIA and state police to investigate cases, and the authority to take over cases from state law enforcement if deemed necessary for national security. By strengthening India's internal security framework, the NIA Act plays a crucial role in combating terrorism and related offences.

Terrorist Financing

India is a member of the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), the Asia/Pacific Group on Money Laundering, and the Eurasian Group on Combating Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing. It faces serious threats from terrorism and terrorist financing, including from groups like ISIL and Al Qaeda.

The Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA) 2002

PMLA is a crucial law in India aimed at tackling terrorist financing and money laundering. It works alongside the UAPA, which defines and criminalizes terrorist acts and the collection of funds for such activities. While the UAPA addresses the act of terrorism itself, the PMLA focuses on preventing the movement and concealment of illicit funds, including those intended for financing terrorism, and allows for the confiscation of assets obtained through such activities.

Under Section 12AA, every reporting entity must conduct enhanced due diligence before carrying out any specified transaction. "Specified transactions" include:

- Any cash withdrawal or deposit exceeding a prescribed limit,

- Any transaction in foreign exchange above a certain threshold,

- Any high-value imports or remittances,

- Any other transaction or class of transactions, as may be prescribed, that pose a high risk of money laundering or terrorist financing or are considered important in the interest of revenue.

The Indian government has openly acknowledged that passing this legislation was one of the conditions for joining the FATF. The law was subsequently amended in 2012 and 2019, following recommendations from the FATF’s 2010 evaluation and 2013 follow-up report on India. However, over the past two decades, certain controversial provisions which violate international human rights law (IHRL) and conflict with FATF’s own guiding principles have been misused to obstruct the legitimate human rights work of non-profit organizations (NPOs) in India. The PMLA, besides containing provisions that breach IHRL, fails to include internal safeguards to target only those NPOs considered genuinely at risk of money laundering. Instead, all NPOs are subjected to the same strict requirements, disproportionately affecting organizations that pose little or no risk[34].

Terrorist Acts defined in International Instruments

The International Convention for the Suppression of the Financing of Terrorism

The convention which entered into force on 10 April 2002, aims to strengthen international cooperation in preventing and combating the financing of terrorism. It criminalizes the act of providing or collecting funds, directly or indirectly, with the intent or knowledge that they will be used for terrorist activities. This includes acts intended to cause death or serious injury to intimidate a population or compel a government or international organization to act or refrain from acting. The Convention establishes that an offence is committed regardless of whether the funds are ultimately used for terrorist acts. It mandates State Parties to take necessary legal measures to detect, freeze, seize, or forfeit assets linked to terrorist financing. Additionally, it requires States to establish jurisdiction over such offences, ensure strict penalties, and facilitate extradition or prosecution of offenders. The Convention also promotes international cooperation through preventive measures, countermeasures, and the exchange of information and evidence essential for related criminal proceedings.

Term as defined in official documents or government reports

The Second Administrative Reforms Commission (ARC)

The commission chaired by Shri Veerappa Moily, was set up by the Government of India under the Ministry of Personnel, Public Grievances & Pensions to recommend comprehensive reforms in public administration. The Commission addressed key areas such as ethics in governance, e-governance, personnel administration, public order, crisis management, federal polity, and citizen-centric service delivery. One of its significant thematic reports, titled “Combatting Terrorism,” focuses on strengthening India's approach to terrorism within the framework of democratic governance. This report comprises seven chapters: (1) Introduction; (2) Terrorism – Types, Genesis and Definition; (3) Terrorism in India; (4) Dealing with Terrorism: Legal Framework; (5) Measures Against Financing of Terrorism; (6) Institutional and Administrative Measures; and (7) Civil Society, Media and Citizens. The report provides a holistic view of the legal, institutional, financial, and societal dimensions of counter-terrorism and proposes reforms to enhance coordination, accountability, and democratic resilience in India's internal security framework[35].

Terrorist Act defined in Case Laws

Vinit Agarwal Alias Vineet Agarwal vs Union Of India Through The National Investigation Agency

It was held that there was sufficient evidence to classify the activities of the appellants under the ambit of "terrorist acts" pursuant to Section 15, making them liable for punishment under Section 17 of the UAPA. The appellants were found to have criminally conspired with co-accused persons and committed offences under Section 120-B IPC read with Sections 17 and 18 of the UAPA, Section 17 of the Criminal Law Amendment Act, 1908, and Section 201 IPC. The Court emphasized that branding an individual as a terrorist does not require proof of organizational membership; participation in terrorist acts, as broadly defined by the amended provisions of the UAPA, is sufficient to attract liability.

Muhammed Shafi P vs National Investigation Agency[36]

The Court examined the application of Section 15(1)(a)(iiia) of the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967 (UAPA), which defines a "terrorist act" to include any act that damages India's monetary stability through the production, smuggling, or circulation of high-quality counterfeit currency or related materials. The Additional Solicitor General (ASG) contended that the accused had committed offences falling within this provision, emphasizing that Section 15(1)(a) provides illustrative, not exhaustive, methods of committing terrorist acts. However, the accused argued that mere smuggling of gold, without intent to destabilize India's economic security or monetary stability, does not constitute a terrorist act under the UAPA. The Court agreed that while smuggling of gold is punishable under the Customs Act, it would not, by itself, amount to a terrorist act under Section 15(1)(a)(iiia) of the UAPA unless it is shown that the smuggling was intended or likely to threaten India's economic security. Furthermore, the Court clarified that offences under Sections 17 (raising funds for terrorist acts) and 18 (conspiracy and preparation to commit terrorist acts) are not wholly dependent on proving a terrorist act under Section 15. Nonetheless, at the bail stage, without sufficient evidence establishing the intent to threaten economic security, the invocation of UAPA provisions, particularly based solely on gold smuggling, was considered unsustainable.

Kartar Singh vs State of Punjab[37]

In the case concerning the Terrorist and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act (TADA) of 1987, the Court highlighted the essential requirement of intent in defining a "terrorist act," as specified in Section 3(1) of the Act. The definition requires that the act be intended to overawe the Government, strike terror in people, or endanger India's sovereignty and integrity. The Court emphasized that both the TADA Act and UAPA share similar motives for terrorist acts, particularly focusing on threats to national security. Additionally, the case delved into procedural concerns, noting that while the Acts aimed for speedy trials in terrorist-related offences, they also raised significant issues regarding fair trial rights, the presumption of innocence, and the erosion of judicial independence. The case also discussed the requirement of intent in committing terrorist offences under the TADA Act, where it was clarified that abetment or conspiracy to commit terrorist acts, even without direct involvement, could be considered as participation in a terrorist offence. Thus, the intersection of intent and act is crucial in determining guilt, with the Court underlining the constitutional need for fair procedures.

International experience

Australia

The Criminal Code Act 1995, particularly Division 101, lays out a comprehensive legal framework to criminalize and prevent terrorist activities. It defines a range of terrorism-related offences, including engaging in a terrorist act, providing or receiving terrorist training, possessing things, or collecting documents connected with terrorism, and other preparatory acts. The penalties are severe, ranging from 10 years to life imprisonment and apply even if the terrorist act does not occur or is not linked to a specific attack. The law criminalizes both acts done with knowledge and those committed with recklessness as to their connection with terrorism. It also incorporates extended geographical jurisdiction, allowing prosecution for acts committed abroad.

United Kingdom

The Terrorism Act 2000, terrorism is defined as the use or threat of action intended to influence a government or international organisation, or intimidate the public, with the aim of advancing a political, religious, racial, or ideological cause. Such action qualifies as terrorism if it involves serious violence against people, damage to property, risk to life, endangerment to public health or safety, or serious disruption to electronic systems. Notably, any use or threat involving firearms or explosives is automatically deemed terrorism, even if the intent to influence or intimidate is not proven. The definition extends to acts committed outside the UK, and applies regardless of where the persons or property involved are located. Furthermore, actions done for the benefit of a proscribed organisation are also included within the scope of terrorism.

Appearance in official database

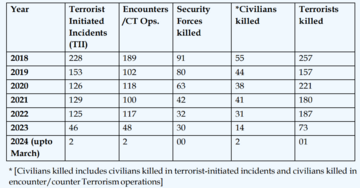

The Annual Report 2023–2024 by the Ministry of Home Affairs provides a detailed overview of India's internal security situation, policy initiatives, and law enforcement measures. It covers areas such as counter-terrorism efforts, border management, disaster response, and the modernization of police forces.

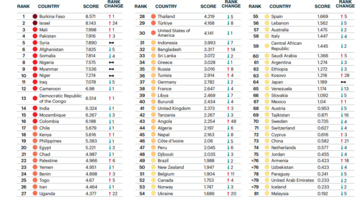

The Global Terrorism Index 2024, published by the Institute for Economics & Peace, provides a comprehensive analysis of the global impact of terrorism based on data trends from the past decade. It examines shifts in terrorist activity, key regional developments, and the evolving threats posed by different groups by offering insights into policy responses and broader socio-economic factors influencing terrorism.

The following data visually traces the evolution of India's national security laws, highlighting how legal frameworks have expanded over time to address various internal and external threats.

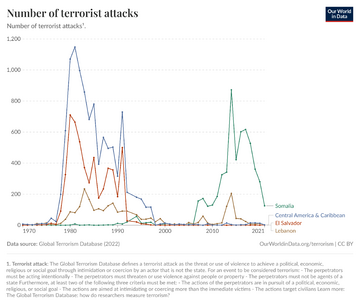

The following image presents data from the Global Terrorism Database (GTD), which records incidents involving the intentional use or threat of violence by non-state actors to pursue political, economic, religious, or social objectives. Only incidents meeting strict criteria—such as intentionality, violence or threat thereof, and sub-national perpetration—are included. The data spans from 1970 to 2021 and has been processed by Our World in Data[41].

Research that engages with terrorist act

Impact of Anti-Terrorism Laws on Human Rights in India (OHCHR)

In the article, the author discusses how anti-terrorism laws rooted in India's colonial past such as MISA, TADA, POTA, and AFSPA have been used to justify excessive force, arbitrary detentions, and human rights abuses in various regions. While some of these laws have been repealed, many of their provisions continue under new laws like the UAPA and the National Security Act, disproportionately targeting marginalized groups and activists, thereby promoting human rights violations and state repression[43].

Tenuous Legality: Tensions Within Anti-Terrorism Law in India

The article by Manisha Sethi examines the evolution and legal tensions within India's anti-terror laws, specifically TADA, POTA, and UAPA. It highlights how these laws erode constitutional safeguards and are often used to suppress dissent rather than combat terrorism[44].

Anti-Terror Law in India a Study of Statutes and Judgments, 2001 – 2014 (Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy)

The report examines the legal landscape surrounding the investigation and prosecution of terrorism-related offences in India. It addresses key issues in the phrasing and implementation of anti-terror laws, their interpretation by courts, and the coordination challenges arising from concurrent jurisdiction between State and Central agencies. Focusing on laws like the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967 (UAPA) and the Maharashtra Control of Organised Crime Act, 1999 (MCOCA), the study seeks to map substantive and procedural provisions, analyze constitutional disputes between the Centre and States, and trace how judicial treatment of terrorism cases differs from ordinary criminal trials[45].

Beyond lethargy: What the 7/11 case reveals about flawed terror trials (The Times of India)

The editorial reflects on the tragic shortcomings of the 7/11 Mumbai blasts investigation and trial, which culminated in the Bombay High Court acquitting all twelve accused. It highlights serious flaws in both the police investigation and the prosecution, describing them as marked by manipulation, incompetence, and a disregard for the victims’ suffering. The nearly two-decade delay in reaching a verdict worsened the injustice, leaving the families of the 187 victims and 824 injured without closure. Although the Supreme Court has stayed the acquittals, the editorial questions whether the real perpetrators will ever be held accountable and whether justice will truly be delivered for the victims[46].

Reference list

- ↑ Terrorism, Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/topic/terrorism/Types-of-terrorism (last visited Apr. 28, 2025)

- ↑ Lt. Gen. V.K. Ahluwalia, Terrorism in India & Successful Counter-Terrorism Strategies, Vision of Humanity (2017), https://www.visionofhumanity.org/terrorism-counterterrorism-strategies-indian-chronicle/

- ↑ Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy, Terrorism and the Law in India (May 2015), https://vidhilegalpolicy.in/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/150531_VidhiTerrorismReport_Final.pdf

- ↑ UAPA S 15(1) a

- ↑ UAPA S 15(1) a (i)

- ↑ UAPA S 15(1) a (ii)

- ↑ UAPA S 15(1) a (iii)

- ↑ UAPA S 15(1) a (iiia)

- ↑ UAPA S 15(1) a (iv)

- ↑ UAPA S 15(1) b

- ↑ UAPA S 15(1) c

- ↑ UAPA S 35

- ↑ UAPA S 38

- ↑ UAPA S 39

- ↑ UAPA S 40

- ↑ https://p39ablog.com/2023/09/criminal-law-bills-2023-decoded-7-analysing-the-terror-offences-framework-under-2023/#_ftn7

- ↑ S 113 (1) of BNS

- ↑ S 113 (1) (a) of BNS

- ↑ S 113 (1) (a) (i) of BNS

- ↑ S 113 (1) (a) (ii) of BNS

- ↑ S 113 (1) (a) (iii) of BNS

- ↑ S 113 (1) (a) (iv) of BNS

- ↑ S 113 (1) (a) (v) of BNS

- ↑ S 113 (1) (b) of BNS

- ↑ S 113 (1) (c) of BNS

- ↑ S 113 (2) (a) of BNS

- ↑ S 113 (2) (b) of BNS

- ↑ S 113 (4) of BNS

- ↑ S 113 (3) of BNS

- ↑ S 113 (5) of BNS

- ↑ S 113 (6) of BNS

- ↑ S 113 (7) of BNS

- ↑ Tarali Neog, Balancing Act: Navigating National Security and Civil Liberties in Anti-Terrorism Legislation Under the Indian Constitution, 7 NLUA L. Rev. 239 (2023), https://nluassam.ac.in/docs/Journals/NLUALR/Volume-7/Article%2010.pdf.

- ↑ Amnesty International, India: Weaponizing Counterterrorism: India's Exploitation of Terrorism Financing Assessments to Target Civil Society, Index No. ASA 20/7222/2023 (Sept. 26, 2023), https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/asa20/7222/2023/en/

- ↑ Second Administrative Reforms Commission (India), Combating Terrorism – Protecting by Righteousness (8th Report of the Second ARC, Department of Administrative Reforms & Public Grievances, Ministry of Personnel, Public Grievances & Pensions, Government of India, June 2008), available at DARPG (India), https://darpg.gov.in/sites/default/files/combating_terrorism8.pdf

- ↑ 2023:KER:40947

- ↑ 1961 AIR 1787

- ↑ Ministry of Home Affairs, Annual Report 2023–2024 (Dec. 27, 2024), https://www.mha.gov.in/sites/default/files/AnnualReport_27122024.pdf.

- ↑ Institute for Economics & Peace, Global Terrorism Index 2024: Measuring the Impact of Terrorism (Feb. 29, 2024), https://www.economicsandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/GTI-2024-web-290224.pdf

- ↑ Bhamati Sivapalan & Vidyun Sabhaney, In Illustrations: A Brief History of India's National Security Laws, The Wire (July 27, 2019), https://thewire.in/law/in-illustrations-a-brief-history-of-indias-national-security-laws

- ↑ Hannah Ritchie, Joe Hasell, Cameron Appel, & Max Roser, Terrorism, Our World in Data, https://ourworldindata.org/terrorism (last visited Apr. 28, 2025

- ↑ Global Terrorism Database (2022) – processed by Our World in Data. “Attacks” [dataset]. Global Terrorism Database (2022) [original data].

- ↑ Liberation, Impact of Anti-Terrorism Laws on the Enjoyment of Human Rights in India, U.N. Human Rights Council, Universal Periodic Review: India, 1st Sess. (Mar. 2008), https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/lib-docs/HRBodies/UPR/Documents/Session1/IN/LIB_IND_UPR_S1_2008_Liberation_uprsubmission.pdf

- ↑ Manisha Sethi, Tenuous Legality: Tensions Within Anti-Terrorism Law in India, 13(2) Socio-Legal Rev. 139 (2017), https://repository.nls.ac.in/slr/vol13/iss2/4/

- ↑ Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy, Terrorism and the Law in India (May 2015), https://vidhilegalpolicy.in/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/150531_VidhiTerrorismReport_Final.pdf

- ↑ Anup Surendranath, Beyond Lethargy: What the 7/11 Case Reveals About Flawed Terror Trials, Times of India, July 27, 2025, 5:00 AM IST, TOI EDIT Page, available at Times of India (online edition), https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/blogs/toi-edit-page/beyond-lethargy-what-the-7-11-case-reveals-about-flawed-terror-trials/