Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights

1. What is Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS)[1]

TRIPS stands for Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights. The Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights is an international legal agreement between all the member nations of the World Trade Organization (WTO). [2]Intellectual property rights are the rights given to persons over the creations of their minds. They usually give the creator an exclusive right over the use of their creation for a certain period. It is a non-tangible asset created by the human mind. Business organizations may use Intellectual property to their advantage to compete worldwide.

Intellectual property is an umbrella term for a set of intangible assets or assets that aren't physical in nature, it is owned and legally protected from outside use or implementation by a person or company without consent. It can consist of many types of assets, including trademarks, patents, and copyrights.

Intellectual property infringement occurs when a third party engages in the unauthorized use of the asset. These assets are created using human intellect. Such property can take many forms and can include artwork, symbols, logos, brand names, and designs.

Companies are diligent when it comes to identifying and protecting intellectual property because it holds such high value in an increasingly knowledge-based economy. Producing intellectual property requires heavy investments in brainpower and the time of skilled labour. This translates into heavy investments by organizations and individuals that shouldn't be accessed by others with no rights.

The purpose of Intellectual property is that it can be used for various reasons such as branding and marketing as well as to protect assets that give a competitive advantage.

2. Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS)

The Trade-Related Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) agreement is crucial for promoting trade in knowledge and innovation, resolving intellectual property trade-related disputes, and ensuring the freedom of World Health Organization (WTO) members to pursue their domestic goals.

TRIPS-related disputes can arise when member countries perceive violations of IP rights or restrictions on trade. WTO's dispute settlement mechanism is used to address such disputes and ensure compliance with TRIPS.

The WTO’s Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), negotiated during the 1986-94 Uruguay Round, introduced intellectual property rules into the multilateral trading system for the first time. The Trips Agreement came into effect on January 1, 1995, and is, to date, the most comprehensive multilateral agreement on intellectual property.)

The TRIPS agreement is one of the most significant WTO accords. India became an associate of the WTO and thus a participant in the TRIPS Agreement in 1995.

The TRIPS Council is responsible for administering and monitoring the operation of the TRIPS Agreement. In its regular meetings, the TRIPS Council serves as a forum for discussion between members on key issues.

In its special sessions, the TRIPS Council serves as a forum for negotiations on a multilateral system of notification and registration of geographical indications (GIs) for wines and spirits.

2.1. - Legal provision(s) relating to Term[4]

The TRIPS agreement is further divided into 7 parts which contain provisions related to Intellectual Property.[5]

Part 1- General Provisions and Basic Principles (Article 1 to Article 8)

Part 2-This part covers the requirements for the availability, scope, and application of intellectual property rights (Article 9 to Article 40)

Part 3- The enforcement of IPRs is the focus of this part (Article 41 to Article 61)

Part 4- This part covers the procedures for obtaining and maintaining intellectual property rights (Article 62)

Part 5- This part deals with the prevention and resolution of conflicts resulting from the provisions of the Agreement (Article 63 to Article 64)

Part 6- This part is about transitional agreements (Article 65 to Article 67)

Part 7- This part of the Agreement deals with a variety of institutional arrangements (Article 68 to Article 73)

2.2- Term as defined in international instrument(s)[6]

“Intellectual Property shall include rights relating to literary, artistic, and scientific works, discoveries throughout all areas of human endeavor, scientific advances, industrial design rights, trademarks, service marks, and commercial names and designations, protection against unfair competition”, states Article 2 of the WIPO(World Intellectual Property Organization)- Central Organization for the Protection of the Intellectual Property laws and the UN expert organization. Intellectual property rights are granted to individuals over the creations of their minds. For a set period, they usually grant the creator exclusive rights to use his or her creations. Intellectual property (IP) is a non-tangible asset developed by the human mind. Business organizations may use IP to gain a competitive advantage and drive their growth. IP ownership interests, like any other property, can be assigned, licensed, or otherwise passed to third parties.

Internationally, IPR is valued and exchanged. The WTO’s TRIPS(Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights) agreement recognises the importance of IP in international trade.

2.3- Principles of TRIPS[7]

A key principle in the WTO is that of non-discrimination. It applies to trade in goods, trade in services and IPRs. It has two components: national treatment, and most-favored-nation (MFN) treatment. The essential principles on the national and most- favored nation treatment of foreign persons are found in Articles 3,4 and 5 and they apply to all kinds of intellectual property covered by the Agreement. These obligations apply not only to substantive standards of protection, but also to issues relating to the availability, acquisition, scope, maintenance and enforcement of intellectual property rights, as well as issues relating to the use of intellectual property rights that are specifically addressed in the Agreement. While the national treatment clause forbids discrimination between a member’s own nationals and the nationals of other members, the MFN treatment clause forbids discrimination between the nationals of other members.[8]

Procedures for notifying and sharing information: the most-favoured nation[7]

The TRIPS Agreement allows WTO members exceptions to the non-discrimination principle known as most-favoured-nation treatment (MFN), that is where a country normally does not discriminate between rights holders from different trading partners. But they must notify the TRIPS Council — in other words the WTO’s membership — if the exceptions arise from agreements that already existed when the TRIPS Agreement took effect.

The most-favored-nation clause requires a country to extend the same trade terms to all trading partners. The MFN clause is the founding principle of the World Trade Organization, with notable exceptions under WTO rules.

Notification under Article 3

Article 3 on national treatment requires each member to accord to the nationals of other members treatment no less favourable than that it accords to its own nationals with regard to the protection of IP. With respect to the national treatment obligation, the exceptions allowed under the four pre-existing WIPO treaties (Paris, Berne, Rome and IPIC) are also allowed under TRIPS.

An important exception to national treatment is the so-called ‘comparison of terms’ for copyright protection allowed under Article 7(8) of the Berne Convention, as incorporated into the TRIPS Agreement. If a member provides a term of protection in excess of the minimum term required by TRIPS, it does not need to protect a work for longer than the term fixed in the country of origin of that work. In other words, the additional term can be made available to foreigners on the basis of ‘material reciprocity’.

Exceptions can be allowed to the national treatment principle for judicial and administrative procedures – for instance, foreign applicants for IP protection may be required to provide an address for service or a local agent in that jurisdiction. But Article 3.2 requires that such exceptions be necessary to secure compliance with laws and regulations which are consistent with the TRIPS Agreement and that such practices not be applied so as to constitute a disguised restriction on trade.[8]

Notifications under Article 4(d)

The TRIPS Agreement’s Article 4 on most-favoured-nation treatment provides that, with regard to the protection of intellectual property, any advantage, favour, privilege or immunity granted by a member to the nationals of any other country shall be accorded immediately and unconditionally to the nationals of all other members. There are certain exceptions to this obligation. Subparagraph (d) of that article, exempts any advantage, favour, privilege or immunity accorded by a member deriving from international agreements related to the protection of intellectual property which entered into force before the WTO agreement entered into force, provided that such agreements are notified to the TRIPS Council TRIPS and do not constitute an arbitrary or unjustifiable discrimination against nationals of other members.

Notifications under Article 5

Article 5 of the TRIPS Agreement provides that national and MFN treatment obligations do not apply to procedures provided in multilateral agreements concluded under the auspices of WIPO relating to the acquisition or maintenance of IPRs. This Article recognizes that certain WIPO agreements, such as the Patent Cooperation Treaty, the Madrid Agreement Concerning the International Registration of Marks (Madrid Agreement) and the Protocol to that Agreement (Madrid Protocol), and the Hague Agreement Concerning the International Registration of Industrial Designs, provide for a system of international applications only open to persons that are nationals or residents of signatory countries or have a real and effective industrial or commercial establishment in those countries. The exception in this Article only applies in respect of procedures relating to the acquisition and maintenance of rights, not to the substantive standards of protection themselves. The exception contained in Article 5 is not limited to pre-existing WIPO agreements.[8]

2.4- [9]Case law on TRIPS[9]

- Novartis A.G vs Union of India (2007)

This case was the first instance of questions regarding India’s compliance with the TRIPS Agreement being brought before the Indian courts.

The complainant, in this case, was a Swiss pharmaceutical company, namely Novartis, which sought to patent a cancer drug called Glivec. However, after the Patent Office denied the application, the Complainant brought a claim before the Indian High Court of Madras, seeking a declaration that Section 3(d) of the Patent Act of 1970 as substituted by the Patents(Amendment) Act, 2005 was not in compliance with the TRIPS Agreement and/or that it was unconstitutional or arbitrary, illogical, vague and offends Article 14 of the Constitution of India.

2. People's Union for Civil Liberties vs. Union of India & Another[10]

Shri Shanti Bhushan, while replying to the arguments advanced by Shri Grover submitted that Shri Grover primarily reiterated and adopted the arguments which had been advanced by the other Counsels on anticipation, novelty and obviousness. Since appropriate replies were given by the Appellant to all those arguments it was not necessary to deal with the same any further. In response to Shri Grover's contention that the grant of patents in 35 or more countries should not have any persuasive value as the laws in those countries were different and his reference to the different Articles, particularly articles 1, 7, 8 and 27 of the TRIPS Agreement, Shri Shanti Bhushan said that the reference to these Articles by Shri Grover was in an endeavour to persuade the Court not to interpret section 3(d) of the Act consistently with the TRIPs Agreement. However, this approach to the interpretation of section 3(d) would be hopelessly unjustified and nothing in the Articles of the TRIPS Agreement supported this contention. A reference to the Article 1 showed that the protection to Intellectual Property was guaranteed by the TRIPs Agreement and the same could not be reduced and permitted the members in their laws to give more extensive protection than was required by the TRIPs provided such more extensive protection did not contravene the provisions of the Agreement. In fact, he said, it was settled law as per the decision of the Supreme Court of India that an Act of Parliament as far as possible, ought to be construed in a manner so as to conform to international agreements to which India was a party. He referred in that connection to a decision of the Supreme Court in (2005) 2 SCC 436 where it is stated:41. Thus international treaties have influenced interpretation of Indian law in several ways. This Court has relied upon them for a statutory interpretation, where the terms of any legislation are not clear or are reasonably capable of more than one meaning. In such cases, the Courts have relied upon the meaning which is in consonance with the treaties, for there is a prima facie presumption that Parliament did not intend to act in breach of international law, including State treaty obligations. It is also well accepted that in construing any provision in domestic legislation which is ambiguous, in the sense that it is capable of more than one meaning, the meaning which conforms most closely to the provisions of any international instrument is to be preferred, in the absence of any domestic law to the contrary. In this view, section 3(2) (d) is to be read keeping in view the Paris principles.

3. [11]Subject matters of Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights

The Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights(TRIPS) Agreement covers seven main types of intellectual property. The following are:

- Copyrights

- Trademarks

- Geographical indications

- Industrial designs

- Patents

- Layouts designs for integrated circuits

- Undisclosed information (trade secrets)

1. Copyrights

According to the Agreement, copyright protection shall extend to expressions and not to ideas, procedures, methods of operation or mathematical concepts as such.

Copyright is granted to literary work, musical work, dramatic work, pictorial work, sculptural work, architectural work, choreographic work, graphic work, motion picture, sound recording, audio-visual work, computer programmes, etc. The owner of a copyright has the right to exclude others from reproducing, distributing, preparing derivative works, performing, displaying, or using the work covered by copyright for a specific period of time. The essence of copyright is originality, which implies that the copyright owner or claimant originated the work. However, a work of originality need not be novel. Originality does not imply novelty in copyright law; it only implies that the copyright claimant did not copy from someone else.

For the first time at the international level, rental rights for phonograms, films and data compilations and minimum standards of protection for works not belonging to natural persons are being granted. The protection of software, in particular computer programmes which, whether in source or object code, should be protected as literary works under the Berne Convention, which includes Articles 9-14.

2. Trademarks

According to this section of Part II of the Agreement, any sign, or any combination of signs, capable of distinguishing the goods or services of one undertaking from those of other undertakings, is capable of constituting a trademark and therefore eligible for registration as a trademark. The holder of a trademark has the right to exclude others from using that trademark.

Based on the provisions, including Article s 15-21 laid down in the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property, the TRIPS Agreement defines the signs' criteria necessary for eligibility for trademark or service mark protection, laying down assignment prerequisites, terms of protection, and exploitation of the entitled rights.

3. Geographical Indications

Geographical indications identify a good as originating in the territory of a Member, or a region or locality in that territory, where a given quality, reputation or other characteristic of the good is essentially attributable to its geographical origin.

Several commercial products are traditionally produced in a specific geographically definable region. Where these products are accredited specific criteria essentially attributable to their geographical provenance, the geographical indication becomes, in trade relations, the reliable "carrier" of qualifying product characteristics. Geographical indications are then ascribed the function and importance of trademarks and are entitled to legal protection.

Articles 22-24 incorporates the principles of the Lisbon Agreement for the Protection of Appellations of Origin and their International Registration signed in 1958 and revised in 1967.

Under the Agreement Members are committed to adopt legislation which prevents the use of indications likely to mislead the public as to the geographical origin of the goods or to constitute an act of unfair competition. Members should also refuse or invalidate the registration of a trademark which contains or consists of a geographical indication with respect to goods not originating in the territory indicated, if use of the indication in the trademark is of such a nature as to mislead the public as to the true place of origin.

Wines and spirits

More restrictive provisions have been developed for wines and spirits. Here, Members shall provide the legal means for preventing the use of a geographical indication identifying wines or spirits as not originating in the place indicated by the geographical indication in question, even where the true origin of the goods is indicated or where the geographical indication is accompanied by corrective supplements such as "kind", "style", "imitation" or similar. The holder of the right does not have to show that there is a likelihood of confusion or that there is unfair competition; the use of an identical or similar indication of origin is itself an infringement.

Section 3 also comprises exceptions to given provisions. Previously existing protection of rights may not be diminished because of the Agreement. Members may refuse protection of geographical indications, which have become generic terms of product description in that Member.

The implementation process must avoid distortion of prior trademark rights. Where a trademark right has been applied for or registered in good faith, or where rights to a trademark have been acquired through use in good faith either before the date of application of the Agreement in that Member or before the geographical indication is protected in its country of origin, implementing measures should not prejudice eligibility for or the validity of the registration of a trademark, or the right to use a trademark, which is identical with, or similar to, a geographical indication.

Members are not obliged to protect geographical indications which are not or cease to be protected in their country of origin, or which have fallen into disuse in that country.

4. Industrial Designs

According to Articles 25-26 of the Agreement, Members shall provide for the protection of independently created industrial designs that are new or original.

Also based on the Paris Convention, yet going far beyond that, the Agreement undertakes to protect industrial designs for a minimum period of ten years. This enables the right holder to prevent third parties not having the holder's consent from manufacturing, importing or selling products embodying the protected design, when such acts are undertaken for commercial purposes. Requires protection for new or original industrial designs and permits members to refuse protection for designs dictated essentially by technical or functional considerations. Grants rights to prevent unauthorized acts such as making, selling, or importing articles bearing or embodying a design which is a copy of the protected design, with a protection term of at least 10 years.

5. Patents

A patent is an IPR granted to inventors. The inventor, as owner of the patent, has the right to exclude any other person from making, using, selling, or importing the invention protected by the patent, for a certain period of time in a given territory, also provide exclusive rights for inventions in all fields of technology, provided they are new, involve an inventive step, and are capable of industrial application, all are being included under Articles 27-34.

Before the adoption of the Agreement, countries were free to determine the terms for patentability, the rights conferred to patent holders and the duration of patent protection. The establishment of areas of non-patentability was also left to countries' own discretion. It is not surprising that patent law was thus tailored to follow countries' own economic interests. This resulted in diverging standards among Members, which inevitably caused substantial tensions in global trade relations.

Partly based on the Paris Convention in its latest version, Section 5 lays down minimum standards for patent law at the international level, thus mitigating this longstanding problem among Members. According to the provisions of the Agreement, Members are committed to make patents available for any invention, whether products or processes, in all fields of technology without discrimination as to the place of invention and whether products are imported or locally produced, provided the requirements of novelty, inventiveness and industrial applicability are fulfilled. Mandatory terms of application comprise complete and sufficiently clear disclosure of the invention as to the method of use and production.

6. Layout Designs

In Section 6 of Part II of the Agreement, Members agree to provide protection to the layout-designs (topographies) of integrated circuits, where articles 35-38 set forth the obligations of WTO members to protect the original layout-designs of integrated circuits, recognizing their unique intellectual property status.

Authorization of the right holder is necessary for importing, selling, or otherwise distributing for commercial purposes a protected layout-design, an integrated circuit in which a protected layout-design is incorporated, or an article incorporating such an integrated circuit only in so far as it continues to contain an unlawfully reproduced layout-design.

As regards the Treaty on Intellectual Property in Respect of Integrated Circuits, the TRIPS Agreement gives additional terms of protection for this subject matter, i.e. minimum protection for ten years, and provides for minimum penalties for infringements. Also, establishes the rights of holders of protected layout-designs, granting them the exclusive authority to reproduce, import, sell, and distribute the protected layout-designs or integrated circuits incorporating them. Addresses limitations, exceptions, and compulsory licensing, allowing members to permit certain uses of a protected layout-design without the right holder's authorization under specific conditions, such as for public non-commercial use or to remedy anti-competitive practices.

7. Protection of Undisclosed Information (Trade secrets)

Recognizing the commercial value of trade secrets and non patentable "know-how", TRIPS requires Members to develop national legislation to protect such information from being disclosed to, acquired by, or used by persons without the consent of the person who is lawfully in control of it, in a manner contrary to honest commercial practices. To be awarded protection, such information must be secret, have commercial value because it is secret, and have been subject to reasonable steps to keep it secret.

Likewise, these provisions are valid, under defined circumstances, for information submitted to governments (i.e. undisclosed tests or other data submitted as a condition of approving the marketing of pharmaceutical or agricultural chemical products), giving protection against unfair commercial use under Article 39, section 7 of Part II.

Also in Article 39(3) addresses the protection of data submitted to governments or governmental agencies, particularly in the context of obtaining marketing approval for pharmaceutical or agricultural chemical products. Members must protect such data against unfair commercial use and disclosure, except where necessary to protect the public or unless steps are taken to ensure the data is protected against unfair commercial use.

3.1 Slight differences and nuances on the TRIPS[12]

The changing face of the world today has precipitated a growing need to address the subject. Intellectual Property falls broadly into two categories: industrial property and copyright. Industrial property includes laws relating to patented inventions, trademarks and designs. Literary and artistic works fall under copyright law. These works may include poetry, drama, dance, novels, music, films, paintings, photographs, and other fine art and designs. Artists and their performances are included in copyright issues, whether this pertains to stage, screen, recordings, broadcasts or media programs.

Copyright law protects the expression of an idea and not the idea itself. There is no requirement for novelty or uniqueness as there is in patent law. The term „original‟ in the copyright law means that the work originated with the author. The things covered by copyright are such as literary creations, films, dramatic works, musical compositions, artistic creations, sound recordings, music. The things which may not be covered by copyright are such as ideas, recipes, names, titles or short phrases, works lacking originality e.g. the phone book, facts, scope of copyright and others. There are two kinds of rights: moral rights to protect personality of author, and economic rights to bring economic benefits.

Patent is an exclusive right granted for an invention, which is a product or a process that provides a new way of doing something, or offers a new technical solution to a problem. With a patent the limited monopoly right granted by the state enables an inventor to prohibit another person from manufacturing, using or selling the patented product or from using the patented process, without permission. Generally a period of patents is 20 years. Patent laws are updated, together with copyright laws. The latter has specific ramifications for issues of piracy, which has become rampant as a result of the ease with which applications, especially music and film, can be downloaded from the Internet. Copyright and piracy laws are required to safeguard against such eventualities. Enhanced protection is needed with respect to new methods of communication technology that both allow the expansion of knowledge and creativity, and simultaneously place these in danger of copyright infringement.

The entities such as inventions in all fields of technology, whether products or processes, if they meet the criteria of novelty; non-obviousness; industrial application (utility) can be patented. There are two categories for patentable inventions: products and processes grant of patent. Patents are granted by national patent offices after publication and substantial examination of the applications. In India provisions exist for pre-grant and post grant opposition by others. They are valid within the territorial limits of the country. Foreigners can also apply for patents.

3.2 Variations in TRIPS of usage in research and per civil society[13]

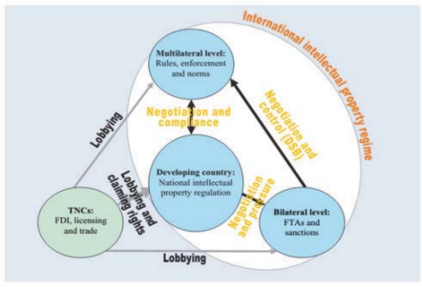

The intellectual property rights (IPRs) are regulated varies strongly across preferential trade agreements (PTAs) characterized by large differences in power and innovative capacity across member states. Computational text analysis on the IPR sections included in 467 PTAs signed between 1994 and 2020 allows us to test expectation. The results show that, indeed, power asymmetries combined with asymmetries in innovative capacity drive deep IPR provisions. At the same time, many states include provisions regulating IPRs in their preferential trade agreements (PTAs). These provisions can require PTA member states to sign up to international conventions on IPRs, lengthen protection periods, impose protection for geographical indications, or ensure enforcement of IPRs.

Both more and less innovative firms will lobby their governments to see their preferences reflected in the country’s trade policies. They can offer financial, campaigning and electoral support to politicians in exchange for support for their positions. Moreover, they may use information and expertise to sway decision-makers. Which side wins should largely depend on the relative strength of the two sides: the more highly innovative firms and industries exist in a country, the more that country should favor the internationalization of IPRs. By contrast, the fewer innovative firms and industries exist in a country, the more that country should strive to avoid the internationalization of IPRs or at least should only want to make shallow commitments.

Countries with lower innovative capacity try to avoid deep IPRs in PTAs; but they are only able to do so if they possess sufficient bargaining power. This means that the rules written down in many PTAs do not equally serve the current interests of all members. In less innovative economies, the strict IPR provisions included in some PTAs may make it harder for local firms and sectors to build capacities and finally become globally competitive innovators themselves. A better understanding of the driving forces behind the internationalization of IPRs, thus is not only of scholarly but also of broader public interest.

3.3 Functional variations across regions/states/High Courts of TRIPS

The implementation and enforcement of the TRIPS (Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights) Agreement in India exhibit notable variations across different regions, states, and High Courts. These differences stem from the decentralized nature of India's judiciary and the discretion afforded to courts in interpreting and applying intellectual property (IP) laws[14].

Judicial Interpretations and Enforcement

Indian High Courts have demonstrated diverse approaches to IP enforcement, particularly concerning injunctions and the application of TRIPS flexibilities. [15]For instance, the Delhi High Court, in cases like Ellora Industries v. Banarsi Dass, has addressed the concept and scope of 'passing off' actions, emphasizing the likelihood of consumer confusion due to misrepresentation. Such decisions highlight the court's proactive stance in protecting trademark rights.

In Imperial Tobacco Co v Registrar, Trade Marks the Calcutta High Court explained to the following concept of ‘geographic term’ namely: “Geographical terms and words in common use designate a locality, a country, or a section of country which cannot be monopolized as trade marks; but a geographical name not used in geographical sense to denote place of origin, but used in an arbitrary or fanciful way to indicate origin or ownership regardless of location, may be sustained as a valid trademark.”

In Tata Sons Ltd. Vs. Manoj Dodia and Others (2011) The Court held that well known trademark is a mark which is widely known or recognized by the relevant general public. The Court referred to Article 6 bis of Paris Convention, 1967 and also Article 16 of TRIPS Agreement 1994. The Court observed that as per Article 16 of TRIPS Agreement 1994, in determining whether the trademark is well known, the members shall take account of the knowledge of the trademark in relevant sectors of the public, including knowledge in the member concerned which has been obtained as a result of the promotion of the trademark. India became a signatory of the TRIPS Agreement in the year 1994.[16]

Conversely, other High Courts may adopt different standards or interpretations, leading to inconsistencies in IP enforcement across the country. These disparities can influence the predictability of legal outcomes for IP rights holders and affect the overall IP landscape in India.

Regional Implementation of TRIPS Flexibilities

The TRIPS Agreement allows member countries to incorporate flexibilities, such as compulsory licensing and parallel imports, into their national laws. India has utilized these provisions to balance IP protection with public interest, especially in the pharmaceutical sector. However, the application of these flexibilities can vary regionally. For example, the interpretation of Section 3(d) of the Indian Patent Act, which prevents the patenting of new forms of known substances unless they enhance efficacy, has been subject to differing judicial opinions.

Case Studies Highlighting Regional Variations

[17]In the case of Novartis AG v. Union of India, the Supreme Court upheld the rejection of a patent application for a modified cancer drug, emphasizing the need for enhanced therapeutic efficacy. This landmark decision underscored India's commitment to preventing 'evergreening' of patents and ensuring access to affordable medicines. Such rulings reflect how higher judiciary interpretations can influence IP enforcement nationwide, though lower courts may still exhibit regional variations.

3.4 Use of different Nomenclature across regions/states/High Courts of TRIPS

The implementation of the TRIPS (Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights) Agreement in India has led to the adoption of various terminologies across different regions, states, and High Courts. While the core principles of TRIPS are uniformly recognized, the specific nomenclature used can differ, reflecting local legal traditions and interpretations.

Geographical Indications vs. Trademarks

A notable example of differing terminology is the distinction between "Geographical Indications" (GIs) and "Trademarks." The Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration & Protection) Act, 1999, was enacted to comply with TRIPS, highlighting differences such as:

- Rights Holder: Trademarks confer rights to individuals or companies, whereas GIs pertain to a community's collective rights.

- Licensing: Trademarks can be licensed to others; GIs, representing collective heritage, typically cannot be licensed.

- Scope of Application: Trademarks apply to various goods and services, while GIs are often associated with specific agricultural products, handicrafts, or other region-specific goods.

Language and Trademark Infringement[18]

The interpretation of trademark infringement concerning language variations also showcases regional judicial approaches. The Delhi High Court, in New Bharat Overseas v. Kian Agro Processing Private Limited & Ors., addressed whether using a registered trademark in a different language constitutes infringement. The court held that translating a registered trademark into another language still amounts to infringement, emphasizing the importance of protecting trademarks across linguistic variations.

The Hon’ble High Court of Delhi also relied the case of Coca-Cola Company v. Bisleri International (P) Ltd., 2009 SCC OnLine Del 3275, where it was held that exporting goods from a country was to be considered as a sale within the country from where the goods were being exported and the same amounted to infringement of a trade mark.

Judicial Interpretations of Patent Terms

Variations also emerge in judicial interpretations of patent-related terms. The Calcutta High Court upheld the constitutionality of Section 53 of the Patents Act, 1970, aligning it with TRIPS by affirming that the patent term in India is 20 years from the filing date. This decision underscores the judiciary's role in harmonizing domestic law with international agreements.

4. International Experience in Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights

India is a member of the WTO, which came into being on January 1, 1995. The WTO administers the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), which is an international agreement among countries to promote free international trade in goods. The WTO is a package deal in that its members must abide by the GATT agreement and a series of other international agreements. One such agreement is the TRIPS Agreement. India is also a member of the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property, the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT), as well as the Budapest Treaty on the International Recognition of the Deposit of Microorganisms for the Purposes of Patent Procedure[21].

Since TRIPS came into force, it has been subject to criticism from developing countries, academics, and non-governmental organizations. Though some of this criticism is against the WTO generally, many advocates of trade liberalisation also regard TRIPS as poor policy. TRIPS's wealth concentration effects (moving money from people in developing countries to copyright and patent owners in developed countries), and its imposition of artificial scarcity on the citizens of countries that would otherwise have had weaker intellectual property laws, are common bases for such criticisms. Other criticism has focused on the failure of TRIPS to accelerate investment and technology flows to low-income countries, a benefit advanced by WTO members in the lead-up to the agreement's formation. Statements by the World Bank indicate that TRIPS has not led to a demonstrable acceleration of investment to low-income countries, though it may have done so for middle-income countries[22].

4.1 Other countries have sought to define, operationalise and collect data regarding the TRIPS[23]

“Developed countries, which host the world’s largest intellectual property-producing industries, were the key advocates for comprehensive minimum standards of protection and enforcement of IPRs. By contrast, many developing countries, which see themselves mostly as a consumer of intellectual property, felt that stronger standards of protection would serve to limit access to new technologies and products, thereby undermining poor countries’ development prospects. Not surprisingly, the TRIPS Agreement remains one of the most controversial agreements of the WTO.”(Fink, 2004)

It is said that the international architecture of TRIPS Agreement is constructed as one size fits all arrangement. This has caused many discussions as TRIPS imposes uniform standards on all member countries. The difference is that the most enthusiastic supporters of TRIPS, which are developed member countries, during the course of their economic development were slow and hesitant in accepting the uniform intellectual property standards imposed from externally. This helped them in gaining economic benefit compared to others. So they protected most the IP of their citizens and were not so worried for the protection of IP of foreign citizens (Dixon & Greenhalgh, 2002).

One important conclusion that emerges from the history of institutional development is that it took the developed countries a long time to develop institutions in their earlier days of development. These institutions typically took decades, and sometimes generations, to develop.

This is like to kick the ladder that helped them to climb higher, so when certain level is reached, they impose to the undeveloped or developing countries to respect the rules. (Chang, 2003)

As noted by Maskus, (cited in Dixon & Greenhalgh, 2002), because TRIPS confers much stronger rights on the developers of intellectual property, the short to medium term impact of TRIPS will be to effect a change in the distribution of gains from intellectual property away from intellectual property users and towards the developers of protected information and intellectual property. This benefits information creators in both the developed and developing world, but as noted above, this will massively favor the developed world.

In their article Archibugi and Filippetti, (2010) raise some thesis in assessing the TRIPS Agreement:

1. TRIPS aims to impose the western IP regime to the rest of the world. The IPRs regime has become stronger in the western world. This trend began in the United States where the scope of IPRs has been extended to additional areas (e.g. software) and additional subjects (public research centers and universities), the other western countries have imitated the same trend. Through TRIPS it is spread the western logic to all countries.

2. TRIPS is the outcome of nondemocratic process driven by a club of US corporations. TRIPS has not been debated and negotiated as a global public good. On the contrary it has been strongly pushed by US. In particular it the outcome of the pressures made by a handful of US corporations which have successfully asked their government to act on their behalf.

3. TRIPS may serve the interests of western corporations but not necessarily of western economies. There is no evidence that TRIPS has been advantageous for American citizens at large. On the contrary, it seems that TRIPS has been important to allow Trans - National Corporations (TNCs) to expand their innovative activities globally, relying on stronger IP regimes abroad.

4. TRIPS alone will not lead to an increase in the technology gap between western countries and emerging countries. Both supporters and detractors of TRIPS have put too much emphasis on the economic significance of legal devices regulating intellectual property. By themselves, legal devices can neither impede developing countries from catching up nor allow developed countries to preserve their dominion in technological innovation. It is much more important to concentrate on the economic rather than the legal conditions that allow or impede countries from maintaining or acquiring their knowledge base. ( Archibugi & Filippetti, 2010, p.146)

4.2 Deviations from Indian practice/conceptualisation relating to the TRIPS

India's implementation of the Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) Agreement reflects a nuanced approach that balances international obligations with domestic priorities, particularly in public health and access to medicines. This has occasionally led to deviations from standard TRIPS interpretations, as evidenced by various judicial decisions.

1. Section 3(d) of the Indian Patents Act

A significant deviation is found in Section 3(d) of the Indian Patents Act, which aims to prevent the "evergreening" of patents by disallowing new forms of known substances unless they demonstrate enhanced therapeutic efficacy. This provision was upheld by the Supreme Court of India in Novartis AG v. Union of India, where the court denied a patent for a modified cancer drug, emphasizing the need for genuine innovation over minor modifications. This interpretation aligns with India's objective to make medicines more affordable, even though it diverges from broader TRIPS standards.

2. Compulsory Licensing

India has exercised the TRIPS provision for compulsory licensing to ensure access to essential medicines. In Bayer Corporation v. Union of India, the Indian Patent Office granted a compulsory license to Natco Pharma for the generic production of Bayer's patented cancer drug, Nexavar. The decision was based on factors like the high cost of the drug and its limited availability, highlighting India's commitment to public health over strict patent enforcement. Under Article 30 of the TRIPS Agreement, each subscribing nation could introduce an exception to the exclusive rights conferred by a patent, taking into account the legitimate interest of the patent owners and of the third parties. The parliament in its wisdom has, thus, couched the exclusion to a patent, as provided under section 107A, which has wide language , cannot restricted in the manner as canvassed on behalf of Bayer.

3. Bolar Provision and Exportation for Research

Section 107A of the Indian Patents Act, known as the Bolar provision, permits the use of patented inventions for research and development purposes, including activities necessary for regulatory approvals. In Bajaj Auto Ltd. v. TVS Motor Company Ltd., the Delhi High Court interpreted this provision to allow not only the use but also the export of patented products for research purposes, a broader application than typically observed in other jurisdictions. This interpretation facilitates generic drug manufacturers in India to conduct research and seek approvals in foreign markets during the patent term.

4. Geographical Indications and Passing Off

Indian courts have also addressed the protection of geographical indications (GIs) through common law actions like passing off, even before specific GI legislation was enacted. In Scotch Whisky Association v. Golden Bottling Ltd., the Delhi High Court recognized the GI status of "Scotch Whisky" and restrained the defendant from using the term for products not originating from Scotland. Article 22(1) defines the geographical indications, which identify a good as originating in the territory of a Member, or a region or locality in that territory, where a given quality, reputation or other characteristic of the good is essentially attributable to its geographical origin. This case demonstrates India's proactive stance in protecting GIs, aligning with TRIPS obligations while utilizing domestic legal concepts[24].

4.3 Any learnings or Best Practices in the TRIPS

The Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) Agreement provides a comprehensive framework for the protection and enforcement of intellectual property (IP) rights globally. Over the years, member countries have developed best practices to effectively implement TRIPS provisions while addressing national priorities. Key learnings and best practices include:

1. Utilizing Implementation Flexibilities

Article 1(1) of the TRIPS Agreement allows members the flexibility to determine the appropriate method of implementing its provisions within their legal systems and practices. This enables countries to tailor IP laws to their specific contexts while adhering to international standards[25].

2. Leveraging TRIPS Flexibilities

The TRIPS Agreement includes flexibilities that permit members to adopt measures necessary to protect public health and promote public interests in sectors vital to socio-economic and technological development. For instance, the issuance of compulsory licenses and parallel imports can be employed to ensure access to essential medicines[26].

3. Enhancing IP Enforcement Mechanisms

Establishing robust enforcement mechanisms is crucial for the effective protection of IP rights. This includes implementing procedures for gathering evidence, applying interim measures, granting injunctions, and awarding damages. Such measures help deter infringement and ensure that IP rights holders can adequately protect their interests[27].

4. Promoting Transparency and Public Awareness

Transparency in the administration of IP laws and raising public awareness about IP rights contribute to a more effective IP regime. Educating stakeholders about their rights and obligations under the TRIPS Agreement fosters compliance and encourages innovation.

5. Engaging in International Cooperation

Collaborating with international organizations and other countries facilitates the exchange of best practices and experiences in IP management. Such cooperation can assist in building capacity, harmonizing standards, and addressing cross-border IP challenges.

By adopting these best practices, countries can effectively implement the TRIPS Agreement in a manner that balances the protection of IP rights with public interest considerations, fostering innovation and contributing to economic development.

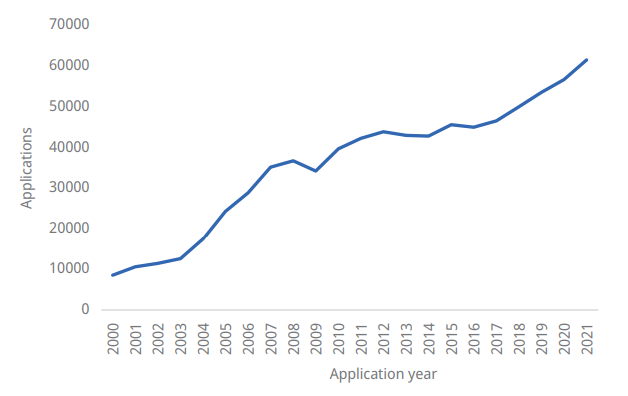

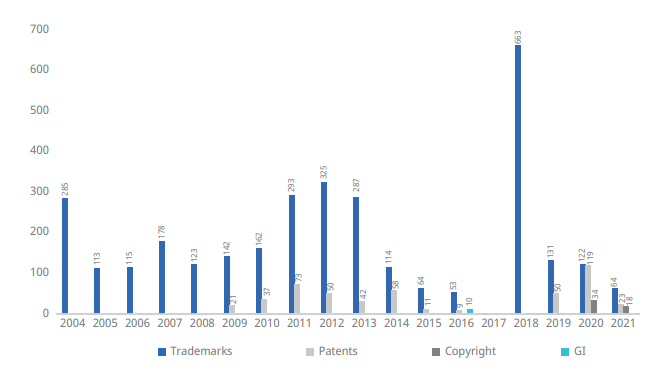

5. Appearance of the TRIPS in Database

The database details of the TRIPS, which show the governmental and non-governmental statistical data information about the variations, changes happened from the past years to the present period.

5.1 Governmental database

6. Research that engages with the TRIPS

Engaged research is a collaborative approach that emphasizes the involvement of societal partners throughout the research process. This method aims to address public interest issues and societal challenges by integrating various stakeholders, including community members, policymakers, and industry representatives. Here’s a detailed overview of engaged research based on the provided information.

6.1 Definition and Importance of Engaged Research

Engaged research is characterized by its commitment to collaboration with societal partners rather than conducting research solely for them. This approach fosters meaningful partnerships that enhance the relevance and impact of research outcomes. Engaged research is often referred to using various terms such as "applied," "community-based," or "participatory," depending on the discipline and context.

6.2 Key Principles of Engaged Research

Collaboration: Engaged research involves active participation from all team members, ensuring that societal partners contribute to every stage of the research lifecycle, from planning to execution and dissemination.

- Capacity Building: This approach focuses on strengthening both human and institutional resources within communities, enabling them to engage effectively in the research process.

- Transdisciplinary Partnerships: Engaged research encourages collaboration across different sectors and disciplines, integrating diverse perspectives to tackle complex societal issues.

- Open Science: Promoting transparency and accessibility in research findings is a crucial aspect of engaged research, facilitating broader community involvement and knowledge mobilization.

- Ethical Considerations: Engaged research prioritizes ethical practices by ensuring that all participants are informed about their roles and rights throughout the study.

6.3 Methodologies in Engaged Research

Engaged research employs various methodologies that can include qualitative and quantitative approaches. It often involves:

- Case Studies: In-depth examinations of specific subjects or phenomena that incorporate both qualitative and quantitative data.

- Community Engagement Activities: Initiatives designed to raise awareness, empower participants, and facilitate dialogue between researchers and community stakeholders.

- Public Engagement: This encompasses a range of activities aimed at involving the public in the design, conduct, and dissemination of research findings.

6.4 Benefits of Engaged Research

- Enhanced Relevance: By incorporating stakeholder perspectives, engaged research ensures that studies address real-world issues that matter to communities.

- Increased Trust: Building relationships with community members fosters trust and encourages ongoing collaboration in future research endeavors.

- Improved Outcomes: Collaborative efforts often lead to more effective solutions that are better aligned with community needs and priorities.

In summary, engaged research represents a shift towards more inclusive and participatory methodologies in academic inquiry. By prioritizing collaboration with societal partners, it not only enriches the research process but also enhances the potential for impactful outcomes that address pressing societal challenges.

7. Challenges in the TRIPS

The Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) has been pivotal in standardizing intellectual property (IP) laws globally. However, its implementation has presented several challenges, particularly for developing countries. Key issues include:

1. Access to Essential Medicines

One of the most pressing concerns is the impact of TRIPS on public health, especially regarding access to affordable medicines. The agreement's stringent patent protections can lead to monopolies, resulting in high drug prices that are prohibitive for many in developing nations. While TRIPS does allow for flexibilities like compulsory licensing, utilizing these provisions can be complex and politically sensitive.

2. Implementation and Compliance

Developing countries often face significant hurdles in aligning their national laws with TRIPS standards. Challenges include limited technical expertise, financial constraints, and the need to balance IP protection with other socio-economic priorities. Ensuring compliance without hindering local innovation or access to knowledge remains a delicate task[29].

3. Protection of Traditional Knowledge

TRIPS primarily focuses on Western notions of IP, which may not adequately safeguard traditional knowledge and cultural expressions prevalent in many developing regions. This oversight can lead to the misappropriation of indigenous knowledge without fair compensation or recognition[30].

4. Enforcement Challenges

Establishing effective enforcement mechanisms for IP rights is resource-intensive. Developing countries may struggle with inadequate infrastructure, lack of trained personnel, and other pressing development needs that compete for limited resources[31].

5. Balancing IP Rights with Public Interest

Striking a balance between protecting IP rights and serving the public interest is complex. Overemphasis on IP protection can stifle competition, hinder the dissemination of knowledge, and limit access to educational materials and technologies essential for development.

Under Section 13(4) of the Patents Act, 1970, the grant of a patent does not guarantee its validity. The underlying principle is that allowing an invalid patent to continue on the register is against the public interest, so every opportunity is provided to remove invalid patents. There are various levels of challenges provided in the Act against a patent application or a granted patent. Such challenges can be made either prior to or after the grant:

– Pre-grant opposition under Section 25(1);

– Post-grant opposition under Section 25(2) before the Patent Office, introduced in 2005;

– revocation under Section 64(1) before the High Court; and

– a counterclaim seeking revocation in a suit for infringement under Section 64(1), in which case the infringement suit and the counterclaim are both transferred to the relevant High Court.

Other challenges to patents or the exercisable rights are compulsory licenses and government use (under Sections 84, 92, 102 and others) and revocation (under Section 66). There has been significant discontent – especially after the 2002 and 2005 amendments – about 265 the multitude of challenge avenues. These provisions for patent challenges may appear to encourage abuse by patent opponents and result in patent grants being held up or delayed almost indefinitely. These apprehensions have been assuaged to a large extent by judicial precedents, which have streamlined the filing of oppositions and dealt with challenges to orders passed in oppositions. In UCB Farchim v. Cipla Ltd, the Delhi High Court confirmed that, once a pre-grant opposition is dismissed and the patent is granted, the order granting the patent cannot be challenged by way of an appeal. The only remedy available is to file a post-grant opposition or a revocation. In Snehlata C Gupte v. Union of India, the practice of filing serial oppositions to hold up the grant of a patent was stopped by the Delhi High Court. The court issued a series of directions preventing delays in patent grants. In Aloys Wobben v. Yogesh Mehra, the Supreme Court categorically held that one person cannot pursue both a revocation application and a counterclaim seeking revocation. These and other decisions have ensured that duplicity and parallel proceedings are avoided to the extent possible.

8. Way Ahead

Stronger IPRs will stimulate creative industries in developing countries and promote foreign direct investment, with an overall positive development outcome. The degree to which the TRIPS Agreement can be expected to encourage FDI and technology transfer is likely to vary significantly not only between developing countries, but also between sectors, between economic activities and between product types. Intellectual property is one of several innovation determinants in health R&D; when assessing impact, intellectual property must be considered in the context of other competencies.

Creatively managed, a global IP regime can be used in the public interest to improve the access of poor populations to new medicines and public health interventions. TRIPS enables countries to establish national patent policies and practices that both meet treaty obligations and address national economic needs and social values. Countries aspiring to use TRIPS to national advantage must build institutional IP capabilities and policies in order to participate in the global marketplace and benefit from emerging technologies.

As a result of the Amendment of 2005, and bringing India’s patent law in compliance with TRIPS, there has reportedly been an upsurge in the number of patent applications filed, and has impacted the economy such that the pharmaceutical industry of India has grown from 6 billion USD in 2005 to 30 billion USD in 2015 and is expected to continue to grow exponentially.

In addition, Article 7 of the TRIPS Agreement emphasizes that the protection and enforcement of IP rights should contribute to technological innovation and the transfer of technology, benefiting both producers and users of technological knowledge in a manner conducive to social and economic welfare. Additionally, Article 8 allows members to adopt measures necessary to protect public health and promote the public interest, provided these measures are consistent with the TRIPS Agreement. These articles suggest that WTO members have the latitude to develop IP policies that accommodate the unique challenges posed by AI advancements.

The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) has been proactive in exploring the intersection of Artificial Intelligence and Intellectual Property policy. Since 2019, WIPO has hosted multiple sessions of the "WIPO Conversation on Intellectual Property and Artificial Intelligence," engaging stakeholders to discuss and address emerging issues related to AI and IP. These discussions have covered topics such as patents, copyrights, and the implications of Artificial Intelligence-generated works.[32]

In conclusion, while TRIPs may have been designed with the intention of promoting global innovation and intellectual property rights, its impact on developing countries has been overwhelmingly negative. From skyrocketing medicine prices and the erosion of agricultural biodiversity to the exploitation of indigenous knowledge and the deepening economic divide between the North and South, the consequences of TRIPs have made it more difficult for developing nations to achieve sustainable development. Moving forward, there is a need for a more equitable approach to intellectual property that recognizes the unique challenges faced by developing countries and allows them to access and build upon global innovations without compromising their own economic, cultural, and social needs.

9. Related Terms in the TRIPS of the Indian concept

Intellectual property rights, intangible assets, trade, agreement, general provisions, copyrights, trademarks, patents, geographical indications, industrial designs, layout designs, trade secrets

10. References

- Trade agreement[6] [22]

- World Trade Organisation[2] [1]

- Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights and Developing countries[3]

- Indian kanoon[4]

- iPleaders - LawShiko[5] [9] [17][27]

- TRIPS Agreement[11]

- CONTOURS AND NUANCES OF INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHTS, COPY RIGHTS AND PATENTS: A FEW EXPLORATIONS[12] [13]

- The TRIPS Agreement and Intellectual Property Rights in India - Lexworth Law [14]

- Geographical Indications under TRIPS Agreement and Legal Framework in India† : Part II [15] [24]

- The Indian Lawyer and Allied Service [18]

- Benchbooks: Philippines and Viet Nam[19][20] [21] [28]

- Power and innovative capacity: Explaining variation in intellectual property rights regulation across trade agreements[23]

- Objectives and Important Provisions of TRIPS Agreement[25]

- Advice on Flexibilities under the TRIPS Agreement[26]

- Implementation of the Trips Agreement and Prospects for its Further Development - SSRN [29] [31]

- TRIPs and Its Consequences for Developing Nations [30]

- Procedures for notifying and sharing information: most-favoured nation[7]

- INTRODUCTION TO THE TRIPS AGREEMENT[8]

- CASEMINE[10] [16]

- WIPO - [32]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/trips_e/trips_e.htm

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/trips_e/intel1_e.htm

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 file:///C:/Users/leyom/Downloads/Trade_Related_Aspects_of_Intellectual_Property_Rig.pdf

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 https://indiankanoon.org/docfragment/136841372/?formInput=trips%20agreement%20% 20doctypes%3A%20judgments

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 https://blog.ipleaders.in/all-you-need-to-know-about-the-trips-agreement/

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/TRIPS_Agreement

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/trips_e/trips_notif4_art4d_e.htm#:~:text=Notifications%20under%20Article%204

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/trips_e/ta_docs_e/modules1_e.pdf

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 https://blog.ipleaders.in/patent-laws-india-compliance-trips-agreement/

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 https://www.casemine.com/search/in/trips%2Bagreement#:~:text=The%20Court%20observed%20that...,a%20result%20of%20the%20promotion

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 https://www.worldtradelaw.net/document.php?id=uragreements%2Ftripsagreement.pdf&mode=download

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 file:///C:/Users/leyom/Downloads/countours%20and%20naunces.pdf

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/03050629.2022.1991337#d1e390

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 https://www.lexworthlaw.com/post/trips-agreement-and-intellectual-property-rights-in-india

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 https://docs.manupatra.in/newsline/articles/Upload/B792FE85-B11E-4AFA-BC8E-9858B07407E4.pdf

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 https://www.casemine.com/judgement/in/56090de0e4b014971117ab36

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 https://blog.ipleaders.in/patent-laws-india-compliance-trips-agreement

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 https://theindianlawyer.in/delhi-high-court-holds-that-defendants-use-of-plaintiffs-registered-trademark-in-a-different-language-amounts-to-infringement-of-trademark

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 file:///C:/Users/leyom/Downloads/wipo-pub-1079-chapter6-en-india-an-international-guide-to-patent-case-management-for-judges%20(1).pdf

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 wipo-pub-1079-chapter6-en-india-an-international-guide-to-patent-case-management-for-judges%20(1).pdf

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 wipo-pub-1079-chapter6-en-india-an-international-guide-to-patent-case-management-for-judges%20(1).pdf

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/TRIPS_Agreement

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 file:///C:/Users/leyom/Downloads/Trade_Related_Aspects_of_Intellectual_Property_Rig.pdf

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 https://docs.manupatra.in/newsline/articles/Upload/B792FE85-B11E-4AFA-BC8E-9858B07407E4.pdf

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 https://thelegalqna.com/objectives-and-important-provisions-of-trips-agreement

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 https://www.wipo.int/en/web/cooperation/policy_legislative_assistance/advice_trips

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 https://blog.ipleaders.in/all-you-need-to-know-about-the-trips-agreement

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 wipo-pub-1079-chapter6-en-india-an-international-guide-to-patent-case-management-for-judges%20(1).pdf

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 https://sociology.institute/sociology-of-development/trips-consequences-developing-nations

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 https://www.wipo.int/en/web/frontier-technologies/artificial-intelligence/conversation