Writ Petition

What is a writ petition?

Writ Petitions (including Public Interest Litigation) are a distinct type of court case which don't deal with general law and order or civil disputes between private parties. Instead, any time that a citizen’s rights (including fundamental rights) are violated, Article 226 of the Constitution of India empowers them to approach the relevant High Court for restoration of the right in question. The aggrieved party petitions the court to issue formal, written orders or directions to a specific government authority for relief. Such cases help reveal how citizens interact with the judiciary as an independent pillar of the state and place their faith in courts to take action against executive overreach, impropriety or lack of action.[1]

Official definition of a writ petition

A writ petition is an application by a petitioner where prayer is made for the issuance of a writ for the redress of his grievances. The Constitution of India, under Articles 32 and 226 confers writ jurisdiction on Supreme Court and High Courts, respectively for enforcement/protection of the fundamental rights of an Individual. A writ petition contains averments or statements sworn, in form of an affidavit.

Legal Provisions

Supreme Court Rules

Under the Supreme Court Rules (Order XXXVIII),[2] a writ petition in the Supreme Court must be filed in Form No. 32, stating petitioner/ respondent details, the nature of the fundamental right infringed, the relief sought, and supporting grounds and documents.

Model High Court Rules by Daksh

The provisions extracted are drawn from the Model High Court Rules governing writ proceedings under Articles 226 and 227 drafted by Daksh Legal.

Under the Rules, every petition under Articles 226 and 227 must be designated as a “writ petition” and presented in the form of a signed memorandum. The memorandum must disclose parties’ details, jurisdictional facts, statutory basis, grounds, reliefs sought, and be supported by affidavits, reflecting procedural formalisation of constitutional remedies.

The Rules require detailed disclosures on maintainability, including availability and exhaustion of alternative remedies, prior writ petitions on the same cause of action, and whether the petition challenges the constitutional validity of any law. This ensures early judicial scrutiny and discourages abuse of writ jurisdiction.

Annexures in writ petitions follow a distinct marking system, with petitioner annexures alphabetically arranged and respondent annexures numbered consecutively. This differentiation underscores the special procedural treatment accorded to writ proceedings as distinct from ordinary original jurisdiction matters.

The Rules permit joint and common writ petitions where parties share similar or common interests, and also recognise writ petitions as the procedural vehicle for Public Interest Litigation. PIL writs must be accompanied by affidavits and prior factual research, reinforcing accountability in constitutional litigation.

Procedurally, writ petitions are structured around preliminary hearings, issuance of rule nisi, service of notice (including electronic service), filing of counter-affidavits, and limited rejoinders. Special urgency is accorded to habeas corpus writs, which are listed before Division Benches and directed toward expeditious disposal.

Interim and ex parte orders in writ proceedings are tightly regulated, requiring service of the petition and annexures along with the order, and placing responsibility on the registry for compliance. Costs may be imposed in writ petitions and writ appeals, reinforcing judicial control over frivolous or abusive filings.

High Court Rules

Karnataka High Court Rules

The Writ Proceedings Rules, 1977[1] designate every designate every petition under Articles 226/227 as a writ petition set out in a specific Form No. I. The petition must succinctly list facts, grounds, and relief claimed in consecutively numbered paragraphs. LegitQuest

Calcutta High Court Rules

Under the Rules relating to applications under Article 226,[3] writ petitions must include particulars as per Schedule A and be type-written in numbered paragraphs.

Madhya Pradesh High Court Rules

MP High Court Rules[2] require petitions to be registered as writ petitions and permit summary dismissal or issuance of rule nisi, with at least 14 days’ time for service where interim relief is sought.

Government Reports

Report No. 245: Arrears and Backlog - Creating Additional Judicial (Wo)manpower

This report[4] examines persistent delays in the justice delivery system and proposes the “Rate of Disposal Method” as an objective basis for calculating the additional judicial strength required to clear existing arrears while managing fresh filings. It recommends structural interventions such as the creation of Special Traffic Courts to divert petty matters and the enhancement of the retirement age of subordinate judiciary to 62 years to stabilise judicial manpower.

Fourteenth Report: Reform of Judicial Administration, Volume I

This foundational report[5] undertakes a comprehensive review of India’s judicial administration with the aim of making justice speedier and more affordable. It analyses the historical evolution and institutional structure of courts, with particular emphasis on judicial recruitment, the organisation of the bar, and the urgent need for reform within the subordinate judiciary.

Fourteenth Report: Reform of Judicial Administration, Volume II

Building on Volume I, this report [6]addresses procedural aspects of judicial functioning, including writ jurisdiction under Articles 32 and 226, administrative adjudication, and the organisation of criminal courts. It recognises that the expansion of writ jurisdiction substantially increased court workloads and recommends procedural efficiencies—such as concise statements of facts—to facilitate quicker disposal.

Seventy-Ninth Report: Delay and Arrears in High Courts and Other Appellate Courts

Focusing specifically on mounting arrears in High Courts, this report [7]proposes the adoption of disposal norms, including the resolution of writ petitions within a one-year timeframe. It further recommends improved administrative support, rationalised listing and grouping of cases, and the appointment of ad hoc judges to address long-pending mattTerritorial Jurisdiction and Cause of Action

In Lt. Col. Khajoor Singh v. Union of India, the Supreme Court held that a writ petition must be filed in the High Court having territorial jurisdiction over the authority concerned. This was reinforced in Oil and Natural Gas Commission v. Utpal Kumar Basu, where the Court rejected forum shopping and held that a writ is maintainable only where a material part of the cause of action arises.

Case Law

Territorial Jurisdiction and Cause of Action

Lt. Col. Khajoor Singh v. Union of India

The Supreme Court held that a writ petition must be instituted before the High Court exercising territorial jurisdiction over the authority against whom relief is sought, and that the mere location or residence of the petitioner does not confer jurisdiction.[8]

Oil and Natural Gas Commission v. Utpal Kumar Basu

Reinforcing territorial discipline, the Court rejected forum shopping and clarified that writ jurisdiction can be invoked only where a material and integral part of the cause of action arises.[9]

Fundamental Procedural Prerequisites

Fertilizer Corporation Kamgar Union v. Union of India

The Court liberalised the doctrine of locus standi by holding that standing depends on the petitioner’s genuine connection with the subject matter, allowing bona fide public-spirited individuals to maintain writ petitions in matters of public importance.[10]

Bandhua Mukti Morcha v. Union of India

This decision revolutionised writ procedure by recognising epistolary jurisdiction, holding that even informal communications may be treated as writ petitions where serious issues of public importance are raised, particularly concerning disadvantaged groups.[11]

Standing and Maintainability

S.P. Gupta v. Union of India

The Court fundamentally reshaped standing in writ jurisdiction by permitting any person with sufficient interest to seek enforcement of constitutional or legal rights on behalf of those unable to approach courts due to socio-economic constraints.[12]

Kushum Lata v. Union of India

In the context of service matters, the Court held that maintainability of writ petitions requires demonstration of a clear legal right and corresponding duty, and ordinarily mandates exhaustion of alternative departmental remedies.[13]

Procedural Discipline and Abuse of Process

Prestige Lights Ltd. v. State Bank of India

The Supreme Court emphasised that writ jurisdiction is discretionary and equitable, and that suppression of material facts or abuse of the judicial process justifies dismissal of a writ petition, even where jurisdiction otherwise exists.[14]

Alternative Remedies

Whirlpool Corporation v. Registrar of Trade Marks

The Court clarified that the existence of an alternative remedy does not bar writ jurisdiction where fundamental rights are violated, principles of natural justice are breached, or the impugned action is without jurisdiction.[15]

L. Chandra Kumar v. Union of India

This judgment reaffirmed that the power of judicial review under Articles 32 and 226 forms part of the basic structure of the Constitution, preserving the supervisory jurisdiction of High Courts over tribunals notwithstanding alternative adjudicatory mechanisms.[16]

Time Limitations, Delay, and Laches

State of Madhya Pradesh v. Bhailal Bhai

The Court held that although writ petitions are not governed by statutory limitation periods, they must be filed within a reasonable time, assessed on factors such as the nature of the right violated and the explanation for delay.[17]

Tilokchand Motichand v. H.B. Munshi

The Court underscored the discretionary nature of writ remedies by holding that delay alone may constitute sufficient ground for refusing relief, even where the petition is otherwise maintainable.[18]

Pendency, Delay, and Speedy Disposal of Writ Petitions

Hussainara Khatoon v. State of Bihar

Linking judicial delay with constitutional rights, the Court held that speedy justice is an essential component of Article 21, particularly in matters involving personal liberty, thereby underscoring the constitutional urgency of writ adjudication.[19]

Judicial Emphasis on Expeditious Writ Adjudication

Rupa Ashok Hurra v. Ashok Hurra

The Court cautioned that excessive delay in adjudicating constitutional remedies undermines the very purpose of writ jurisdiction, emphasising the need for timely and effective judicial intervention.[20]

Interim Orders and Grant of Stay

Rupa Ashok Hurra v. Ashok Hurra

The Court laid down guiding principles for the grant of interim relief in writ proceedings, stressing that such orders must be based on a prima facie case, balance of convenience, and irreparable harm, and that ex parte stays should be granted sparingly.[21]

State of U.P. v. Mohammad Nooh

The Court held that administrative actions should not ordinarily be stayed unless there is a clear case of illegality or violation of principles of natural justice, balancing administrative efficiency with rights protection.[22]

Public Interest Litigation Procedures

Sheela Barse v. Union of India

The Court developed the doctrine of continuing mandamus, allowing courts to retain jurisdiction and monitor compliance in cases involving systemic or institutional violations.[23]

Ramsharan Autyanuprasi v. Union of India

The Court endorsed flexible procedural mechanisms in environmental PILs, including reliance on expert committees and technical assessments to aid judicial decision-making.[24]

Execution and Implementation of Writ Orders

Vineet Narain v. Union of India

This landmark decision strengthened continuing mandamus as a tool to ensure implementation of court directions through periodic reporting and judicial oversight.[25]

Common Cause v. Union of India

The Court emphasised that writ orders affecting policy must be framed in a manner that ensures practical, enforceable, and effective implementation.[26]

Technical and Procedural Requirements

Chief Information Commissioner v. State of Manipur

The Court simplified procedural requirements for writ petitions involving the Right to Information, stressing the need for expeditious disposal while maintaining procedural safeguards.[27]

Mohinder Singh Gill v. Chief Election Commissioner

The Court held that writ petitions must disclose all material facts, particularly in election matters, while ensuring that procedural rigor does not defeat electoral justice.[28]

Modern Procedural Developments

State of Maharashtra v. Prabhu

The Court recognised the need for procedural adaptation to technological change, including acceptance of electronic evidence in writ proceedings.[29]

Union of India v. Cipla Ltd.

The Court laid down principles for handling expert evidence and complex technical material, acknowledging the growing technical complexity of modern writ litigation.[30]

Special Procedural Frameworks

Narmada Bachao Andolan v. Union of India

The Court evolved special procedural safeguards for cases involving large-scale displacement, emphasising inclusive participation and comprehensive impact assessment.[31]

People’s Union for Civil Liberties v. Union of India

The Court developed procedural innovations for rights-based PILs, including continuous monitoring and specialised reporting mechanisms to ensure effective enforcement.[32]

Types of Writ Petitions

Appearance in Official Databases

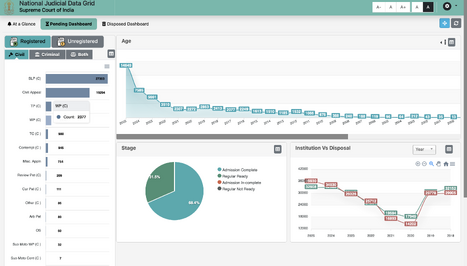

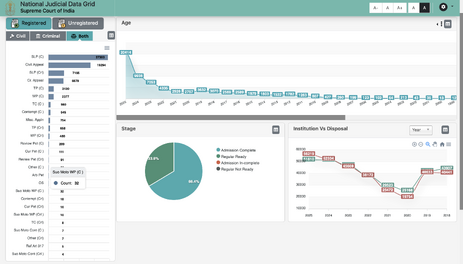

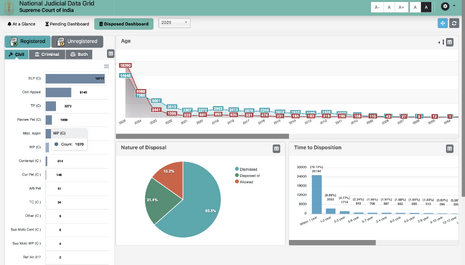

National Judicial Data Grid (NJDG) Supreme Court

National Judicial Data Grid (NJDG) High Court(s)

The National Judicial Data Grid (NJDG) for the High Courts gives the current status of disposed off and pending cases under the writ jurisdiction.

The National Judicial Data Grid subcategories writ cases into eleven case types. They are:

- Service matters

- Cross Objections

- Habeas Corpus

- Execution

- Suo Moto

- Filed by Govt.

- PIL

- Special Subjects

- Industry/Bank/Finance/Insurance/Insolvency

- Company

- Tax/Excise/Duty/Cess.

High Courts website

The High Courts websites do not follow a uniform method of sub categorising writ petition according to case types. Some High Courts generally classify writs as writ (civil), writ(criminal) and PIL while some have adopted subject specific classification. Significantly, the Allahabad High Court follows a broad categorisation of case types under the heads Writ-A, Writ-B, and Writ-C.

Challenges & Variations

- Gujarat identify writs as “SCA” and “SCrA” which makes it difficult for anyone not practising within the court to understand the volume of writs and study deeper.

- Classification within Writs is not harmonised and therefore some courts enable distinction between say civil and criminal writs or service and non-service writs while others do not. There are certain kinds of writs as separate case types based on practical considerations.

- Writs under Article 226 and petitions under Article 227 are classified under the same head and named ‘Writ’

DAKSH Writ Dashboard

The dashboard provides an overview of writ petitions in the Indian High Courts using data reported by High Courts to the Supreme Court, focusing on subject matter, timelines, and outcomes. Writ petitions constitute a significant share of High Court caseloads, with 6.85–7.5 lakh filings annually, accounting for 20–40% of cases, predominantly civil writs. While over half are disposed within a year, a substantial minority face prolonged pendency, with outcomes largely recorded as disposed or dismissed.

Research that engages with Writ Petition

A Study of Karnataka High Court’s Writ Jurisdiction, VIDHI

In this study,[3] case data from writ petitions filed between 2012 to 2016 was examined to see how it has exercised its writ jurisdiction and the challenges it faces in doing so.

The data reveals that writ petitions constitute approximately 60% of the High Court's annual filings, with 30% of these cases categorized as "General Miscellaneous" despite the existence of 129 sub-classifications.

The State Government and local bodies are respondents in 80% of cases primarily regarding land and service issues while demographic data shows a significant gender gap, with 61% of petitions filed by men compared to only 18% by women.

While 69% of cases from the study period have been disposed of, 20% remain "delayed," having been pending for over two years.

Writ Compensation: Issues and Perspectives

This article discusses the judicial evolution of awarding monetary compensation for the violation of fundamental rights, a remedy forged through "Judicial Activism" post-Emergency.

Judgements like Rudul Shah v. State of Bihar established that the Court could award compensation when state lawlessness "shocks the conscience," moving away from traditional conservative views that compensation could not be granted in writ petitions.

The unresolved tensions regarding whether the State or individual officers should be liable are examined, suggesting the State generally pays to avoid deterring officers from public interest decisions, unless the violation was gross and patent.

Writ’ing Wrongs by Compensation: Constitutional Torts and the Need to Provide a Method to the Madness by Rushil Batra

This paper[33] forms part of the broader body of research engaging with the expanding remedial scope of writ jurisdiction. It examines how constitutional courts, while exercising writ powers, have increasingly awarded monetary compensation for fundamental rights violations under the doctrine of constitutional torts.

Through an empirical analysis of High Court decisions from 2019 to 2024, the study demonstrates that although writ courts routinely grant such relief, the reasoning and quantum remain inconsistent and judge-dependent.

The paper therefore contributes to scholarship on the evolution of writ remedies by arguing for structured compensation frameworks that would bring doctrinal coherence to this expanding area of constitutional adjudication.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 DAKSH High Court Writ Dashboard (2022). https://database.dakshindia.org/dashboard/

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Supreme Court Rules 2013, Order XXXVIII.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 https://vidhilegalpolicy.in/research/a-study-of-karnataka-high-courts-writ-jurisdiction/

- ↑ Law Commission of India, 245th Report on Arrears and Backlog: Creating Additional Judicial (Wo)manpower (2014).

- ↑ Law Commission of India, Fourteenth Report on Reform of Judicial Administration, Volume I (1958).

- ↑ Law Commission of India, Fourteenth Report on Reform of Judicial Administration, Volume II (1958).

- ↑ Law Commission of India, Seventy-Ninth Report on Delay and Arrears in High Courts and Other Appellate Courts(1979).

- ↑ Lt Col Khajoor Singh v Union of India AIR 1961 SC 532.

- ↑ Oil and Natural Gas Commission v Utpal Kumar Basu (1994) 4 SCC 711.

- ↑ Fertilizer Corporation Kamgar Union v Union of India (1981) 1 SCC 568.

- ↑ Bandhua Mukti Morcha v Union of India (1984) 3 SCC 161.

- ↑ SP Gupta v Union of India 1981 Supp SCC 87.

- ↑ Kushum Lata v Union of India (2006) 6 SCC 180.

- ↑ Prestige Lights Ltd v State Bank of India (2007) 8 SCC 449.

- ↑ Whirlpool Corporation v Registrar of Trade Marks (1998) 8 SCC 1.

- ↑ L Chandra Kumar v Union of India (1997) 3 SCC 261.

- ↑ State of Madhya Pradesh v Bhailal Bhai AIR 1964 SC 1006.

- ↑ Tilokchand Motichand v HB Munshi (1969) 1 SCC 110.

- ↑ Hussainara Khatoon v State of Bihar (1980) 1 SCC 81.

- ↑ Rupa Ashok Hurra v Ashok Hurra (2002) 4 SCC 388.

- ↑ Rupa Ashok Hurra v Ashok Hurra (2002) 4 SCC 388.

- ↑ State of Uttar Pradesh v Mohammad Nooh AIR 1958 SC 86.

- ↑ Sheela Barse v Union of India (1988) 4 SCC 226.

- ↑ Ramsharan Autyanuprasi v Union of India AIR 1989 SC 549.

- ↑ Vineet Narain v Union of India (1998) 1 SCC 226.

- ↑ Common Cause v Union of India (1996) 1 SCC 753.

- ↑ Chief Information Commissioner v State of Manipur (2012) 7 SCC 1.

- ↑ Mohinder Singh Gill v Chief Election Commissioner (1978) 1 SCC 405.

- ↑ State of Maharashtra v Prabhu (1994) 2 SCC 481.

- ↑ Union of India v Cipla Ltd (2017) 5 SCC 262.

- ↑ Narmada Bachao Andolan v Union of India (2000) 10 SCC 664.

- ↑ People’s Union for Civil Liberties v Union of India (2004) 2 SCC 476.

- ↑ Rushil Batra, ‘Writ’ing Wrongs by Compensation: Constitutional Torts and the Need to Provide a Method to the Madness’ (working paper / journal article).