Debt Recovery Tribunal

What is Debt Recovery Tribunals

Debt Recovery Tribunals (DRTs) are quasi-judicial bodies that were established by the Central government under the Banks and Financial Institutions (RDDBFI) Act, 1993[1] to facilitate the recovery of debts. Appeals from the DRT are heard by the Debt Recovery Appellate Tribunals (DRATs).

These tribunals have the jurisdiction to entertain a wide variety of claims, relating to any secured or unsecured liabilities alleged to be due to banks and financial institutions.[2]The pecuniary minimum for cases over which such tribunals have jurisdiction is Rs. 20 lakh.[3] The exact pecuniary jurisdiction for each DRT is notified by the Central Government.[4]

Official Definition

'DRT' as defined in legislation

'DRT' as defined under Recovery Of Debts And Bankruptcy Act, 1993

As stated in the Long Title, this Act to provide for the establishment of Tribunals for expeditious adjudication and recovery of debts due to banks and financial institutions and for matters connected to it

Section 2(o): “Tribunal” means the Tribunal established under sub-section (1) of section 3[5]

Section 3: The Section provides that the Central Government shall, by notification, establish one or more Tribunals to be known as Debts Recovery Tribunals, to exercise the jurisdiction, powers, and authority conferred on them by or under this Act. The Central Government shall also specify in such notification the areas within which each Tribunal shall exercise jurisdiction for entertaining and deciding applications filed before it.[6]

Composition of DRT

Presiding Officer

Presiding Officer of DRT under Debts And Bankruptcy Act, 1993

Section 4: This section states that the Tribunal shall consist of one person only, who shall be called a Presiding Officer and to be appointed by notification of the Central Government.[7]

Section 5: This section states that a person is qualified to be appointed as the Presiding Officer of a Tribunal only if they are, have been, or are eligible to be appointed as a District Judge.[8]

Presiding Officer of DRT under DRT under Enforcement of Security Interest and Recovery of Debts Laws (Amendment) Act, 2016

Amended Section 4(2)(a): This amendment authorized the Presiding Officer of any other Tribunal constituted under any law in force to also perform the functions of the Presiding Officer of a Debt Recovery Tribunal under this Act, in addition to his existing duties.[9]

Amended Section 4(2)(b)This amendment authorizeda Judicial Member of any other Tribunal established under any law in force to perform the functions of the Presiding Officer of a Debts Recovery Tribunal under this Act, in addition to his role as a Judicial Member of that Tribunal.[10]

Tenure of Presiding Officer of DRT

Tenure of Presiding Officer of DRT under Debts And Bankruptcy Act, 1993

Section 6: This section provides that the Presiding Officer of a Tribunal shall serve a term of five years from the date they assume office and may be reappointed. However, no Presiding Officer shall continue in office after reaching the age of sixty-two years.[11]

Tenure of Presiding Officer of DRT under Enforcement of Security Interest and Recovery of Debts Laws (Amendment) Act, 2016

Section 28: This section provides that the Presiding Officer of a Tribunal shall serve a term of five years from the date they assume office and may be reappointed. However, no Presiding Officer shall continue in office after reaching the age of sixty-five years.[12]

Recovery Officer

Recovery Officer of DRT under Debts And Bankruptcy Act, 1993

Section 7: This section provides that the Central Government shall appoint one or more Recovery Officers to the DRT. Such Recovery Officers shall perform their functions under the general superintendence of the Presiding Officer.[13]

Jurisdiction of DRT

Jurisdiction of DRT under Recovery Of Debts And Bankruptcy Act, 1993

Section 17: The section states that DRT shall have jurisdiction, powers and authority to entertain and decide applications from the banks and financial institutions for recovery of debts[14]

Section 18: The section provides for DRT (except the Supreme Court, and a High Court) to have exclusive jurisdiction, powers or authority to entertain and decide applications from the banks and financial institutions for recovery of debts[15]

Section 19: The section provides that a bank or a financial institution has to recover any debt from any person, it may make an application to the DRT[16]

Pecuniary Jurisdiction of DRT

Pecuniary Jurisdiction of DRT under Recovery Of Debts And Bankruptcy Act, 1993

Section 1(4): The debt owed to a bank, financial institution, or a consortium of such institutions must be at least 10 lakh rupees, or any other amount not less than 1 lakh rupees as may be specified by the Central Government through a notification.[17]

Pecuniary Jurisdiction of DRT under Notification No. S.O 4312(E)

This notification increased the pecuniary jurisdiction of the DRT to a minimum threshold of 20 lakh rupee.[18]

E-filing

Application to DRT under DRT (Procedure) Rules, 1993

Rule 4: The applicant must file the application, in the prescribed form provided in the Rules, either in person, through an authorised agent or legal practitioner, or by sending it by registered post to the Registrar of the appropriate Bench. The application must be submitted in two sets as a paper book, along with an empty file-size envelope with the full address of the defendant. If there is more than one defendant, the applicant must provide additional paper books and envelopes with the full address of each defendant.[19]

Rule 5: This rule sets out the procedure for scrutiny of applications by the Registrar. If the Registrar identifies any defects in an application, the applicant may be permitted to correct them on the spot if the defects are formal in nature. Where the defects are not merely formal, the Registrar may allow such time as deemed appropriate for the applicant to rectify them. If the applicant does not cure the defects within the time granted, the Registrar may, by a written order stating reasons, refuse to register the application. An appeal against such an order of the Registrar shall be filed before the Presiding Officer within fifteen days from the date of the order.[20]

Rule 5A: This rule states that any party aggrieved by an order of the DRT may apply for a review of that order. The review application must be filed within sixty days and must be accompanied by an affidavit verifying the contents of the application.[21]

Rule 18: This rule states that the DRT may pass such orders or take such measures as are necessary or expedient to give effect to its orders, to prevent abuse of its process, or to secure the ends of justice[22]

E-filing to DRT under Debts Recovery Tribunals and Debts Recovery Appellate Tribunals Electronic Filing Rules, 2020

Rule 3 stated that the e-filing of pleadings by applicants shall be optional[23]

E-filing to DRT under Debts Recovery Tribunals and Debts Recovery Appellate Tribunals Electronic Filing Rules, 2021

Rule 3 sub rule (2) stated that e-filing of pleadings shall be compulsory where the debt claimed in the application is one hundred crore rupees or more.[24]

E-filing to DRT under Debts Recovery Tribunals and Debts Recovery Appellate Tribunals Electronic Filing (Amendment) Rules, 2023

Rule 3, sub rule (2) stated that the e-filing of pleadings by applicants is mandatory and any other form of filing shall not be taken on record[25]

E-filing to DRT under Debts Recovery Tribunals and Debts Recovery Appellate Tribunals Electronic Filing (Amendment) Rules, 2025

Rule 4 states that all applications applicant in electronic form, through the e-DRT system.[26]

Procedure of DRT

Procedure of DRT under Recovery Of Debts And Bankruptcy Act, 1993

Section 22: This section states that DRT has not be bound by the procedure laid down by the Code of Civil Procedure, but shall be guided by the principles of natural justice and other Acts and Rules laid down by DRT or DRAT[27]

Procedure of DRT under Debts Recovery Tribunals and Debts Recovery Appellate Tribunals Electronic Filing Rules, 2020

Rule 5: This rule provides that the DRT will regularly upload cause lists, daily orders, and final orders, and will issue directions and notifications electronically through the e-DRT system.[28]

As defined in Official Government Report

T. Tiwari Committe

A 1981 committee headed by Mr. T. Tiwari was set up by the RBI to study the phenomenon of corporate sickness.[29] It also noted that debt recovery cases were treated as ordinary cases, which was a problem in the context of the fact that courts were already burdened with regular cases. It therefore recommended the establishment of special tribunals, i.e., a quasi-judicial setup, exclusively for banks and financial institutions, that would use a summary procedure to quickly dispose off debt recovery cases. It also provided broad outlines for the constitution and functioning of the Special Tribunals.

Narasimham-I Committee

These findings and recommendations were backed by another committee chaired by Mr. Narasimham in 1991 (i.e., the Narasimham-I Committee). This committee went a step further and proposed the formation of quasi-judicial debt collection agencies to expedite debt recovery.[30]

RBI Working Group on the Functioning of Debt Recovery Tribunals

Based on the recommendations of the Second Narasimham Committee Report[31], the Reserve Bank had constituted a Working Group in March 1998 to review the functioning of Debt Recovery Tribunals (DRTs) and to suggest measures for their effective functioning (Chairman: Shri N.V. Deshpande).[32]

In its Final Report, it recommended certain legislative amendments to the RDBFI Act and measures to improve the functioning of DRTs. The recommendations were forwarded to the Government for consideration. In September 1998, the banks were advised, inter alia, to take steps to ensure expeditious recovery procedure at DRTs.

It noted the problem of pendency and stipulated that the presiding officer of DRT should not have more than 30 cases on board on any given date and there should not be more than 800 cases pending before it any given point of time.

As defined in case laws

Union of India & Anr. vs. Delhi High Court Bar Association & Ors

The constitutionality of the RDDBFI Act was challenged on the ground that it violated Article 14 of the Constitution and exceeded the parliament’s legislative competence.[33] The Supreme Court dismissed this and upheld the Act’s validity. It held that “while Articles 323A and 323B specifically enable the legislature to enact laws for the establishment of tribunals, the power of the parliament to enact a law constituting a tribunal such as a banking tribunal is not taken away in relation to the matter specified therein.” Moreover, it held that in exercising its legislative competence, the parliament can offer a mechanism for recovering payments owed to banks and financial institutions.

Standard Chartered Bank vs. Dharmendra Bhoi

However, the Supreme Court has in another case also noted that the jurisdiction of these tribunals is limited to the narrow scope defined in Section 17 of the Act.[34] They cannot encroach upon the jurisdiction of civil courts in matters concerning succession rights, monitoring and enforcing KYC rules, issuing receipts, etc.

Legislative Framework

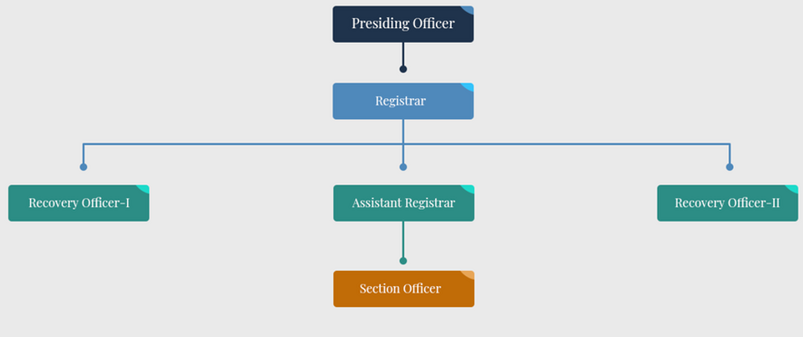

Organizational Structure of DRTs

The following chart describes the institutional setup and structural framework of the DRTs [35]

Provisions Relating to Members of DRTs

- Appointment: Tribunal members are appointed by the Central Government by notification.[36]

- The Debts Recovery Tribunal (Procedure for Appointment as Presiding Officer of the Tribunal) Rules, 1998[37] requires all appointments to be made through a committee consisting of the chief justice of India, three secretaries of the government of India (finance, law, and the department of financial services) and a representative of the governor of the Reserve Bank of India.

- Qualification: A tribunal member must be qualified to be a district judge,[38] i.e., he must have been an advocate/pleader for at least 7 years and be recommended by the High Court for appointment.[39]

- Tenure: 5 years from the date of assuming office, or until the attainment of 62 years of age, whichever is earlier.[40]

- Salaries/Allowances: To be prescribed by the government.[41]

- Removal: By notice in writing. They can also be removed on the ground of proven misbehaviour or incapacity by the Central government, after an inquiry made by the High Court.[42]

Procedural Framework

The Tribunals’ procedure is prescribed by the Central Government in the Debt Recovery Tribunal (Procedure) Rules, 1993.[43] According to these rules when read with the Act, the procedure for debt recovery is as follows:

- Banks need to make an application to the DRT which has jurisdiction in the region in which the bank operates and pay the required fees.[44]

- The defendant shall present a written statement of his defense before the first hearing and set up a counter-claim during the hearing.[45]

- The Tribunal may, after giving the applicant and the defendant an opportunity to be heard, pass such interim or final order.[46]

- The interim order passed against the defendant can restrict him from disposing or transferring his property without the prior assent of the Tribunal.[47]

- DRT after hearing both the parties and their submissions would pass the final judgment within 30 days from hearing. DRT will issue a Recovery Certificate within 15 days from the date of judgment and pass on the same to the Recovery Officer.[48]

- The Tribunal may direct the conditional attachment of the whole or any portion of the property specified by the applicant.[49]

- The Tribunal may also appoint a receiver and confer him all powers to defend the suit in the court and to manage the property.[50]

- Where a certificate of recovery is issued against a company registered under the Companies Act, 1956 the Tribunal may order the sale proceeds of such company to be distributed among its secured creditors.[51]

- Recovery Officers are tasked with the execution of the final decree and are empowered to conduct public auction to realize the debt amount.[52]

The Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest (SARFAESI) Act, 2002,[53] complements the RDFBI in this regard. Borrowers can file applications in the DRTs against action taken for enforcement of security interest under this Act. The Act is applicable to cases where security interest for securing repayment of any financial asset is more than Rs.1 lakh and the amount due is 20% or more of the principal amount and interest thereon.[54]

It has been held that the withdrawal of an action pending before the tribunal under RDDBFI, 1993 is not a prerequisite for resorting to SARFAESI, and that the SARFAESI provides a remedy additional to the RDDBFI that is not ‘inconsistent’ with it.[55]

Subject Matter Jurisdiction

| Particulars | Jurisdiction |

|---|---|

| Debt Recovery | Banks and financial institutions can file an original application before the DRT for the recovery of loans from defaulting borrowers.[56] The minimum pecuniary limit required to be fulfilled is Rs. 20 lakhs.[57] Appeals against orders of a Recovery Officer are also heard by the DRT[58] |

| SARFAESI Act | Under the SARFAESI Act, 2002, the bank or financial institution is empowered to enforce a security interest without the court/tribunal’s intervention[59]. A borrower can approach the DRT for recourse against actions of the secured creditor in realising the security.[60] If such dues are not fully satisfied, even after the sale of secured assets, the bank can approach the DRT to recover the balance amount.[61] |

| IBC | Under Part III, IBC, 2016, the DRT is the adjudicating authority to entertain insolvency pleas against individuals and partnership firms. However, the provisions are not entirely operational as yet[62]. Part III, IBC 2016 has been notified to the extent it applies to personal guarantors to corporate debtors.[63] |

Distribution of Benches

As of February 2024, there are 39 Debt Recovery Tribunals (DRTs) and 5 Debt Recovery Appellate Tribunals (DRATs) established in India.[64]

The territorial jurisdiction of each DRT is determined by the Central notification that established them.[65]

Status of Digitization

The e-DRT project has been implemented in all DRTs and DRATs. It provides access to e-filing, e-payment of fees, cause list generation and a case information system that enables viewing of case status, orders and judgments[66] (on drt.gov.in).

The features of e-DRT are as follows:[67]

- Mechanism and guidelines for paperless filing (“e-filing”) of Original Application (OA), Securitization Application (SA) and other miscellaneous applications across the country

- Provision of necessary information regarding how to use online features of e-DRT Software

- The e-filing system can be used by any Agent (Authorized Legal Practitioner) who has enrolled to practice in the Bar Council of any State in India or by any Petitioner in Person to file cases before DRT or DRAT

The main and supplementary causelists (provided in html format, but also retrievable in .pdf, .doc and .xlx formats on drt.gov.in/#/causelist) provide case number, case name, time of commencement of hearings, and information about the appearing advocate. Some tribunals add remarks to highlight the quantum of the claim pending adjudication.

Hearings are conducted in hybrid form, and all causelists contain a video conferencing link. The Ministry of Finance has issued directions mandating hybrid hearings to comply with the directions of the Supreme Court.[68]

Information disposal data on individual Debt Recovery Tribunals is not publicly available. However, a consolidated statement is published in the annual report of the Department of Financial Services.[69]

Research that Engages with DRTs

Centre for Public Policy Research, ‘A Study on the Effectiveness of Remedies Available for Banks in a Debt Recovery Tribunal: A Case Study on Ernakulum DRT’

This publication notes issues faced by litigants in a DRT, such as pendency (delay of 2-3 years), shortage of staff, a proliferation of stay orders and adjournments.[70]

It suggests providing for accountability measures (such as reporting of disposal data), timely appointment of staff by the Ministry of Finance, closer examination of stay petitions, appointment of an additional Presiding Officer, and legal provisions to ensure time-bound disposal of cases.

CUTS Centre for Competition, Investment and Economic Regulation, ‘Consolidated Project Report on Regulatory Impact Assessment in Indian Financial Sector’

This report took into account the situation between 2013-15 and noted that inadequate capacity and accountability mechanisms in DRTs have led to delays in decision making and consequent recovery of due amounts.[71] It estimated an opportunity cost of around ₹35,000 crore owing to delay in debt recovery (of up to four years) on a consolidated basis (DRT Act and SARFAESI Act). It also noted that low debt recovery has also resulted in credit risk premium of around 300 basis points, resulting in high cost of funds.

It noted that the legislative framework was characterized by short-term fixes, not a comprehensive strategy to manage high non-performing assets, improve debt recovery, and prevent recurring of this episode in future.

It suggested an increase in the monetary threshold for claims (which was implemented in 2018), establishment of 24 new DRTs, provision of technical members, constitution of independent advisory body to recommend candidates to fill vacancies of DRTs, and a stipulation of additional cost for grant of adjournment at increasing rate (0.1 percent of matter) beyond reasonable number. It also suggested SARFAESI-specific legislative changes.

Sujata Visaria, ‘Legal Reform and Loan Repayment: The Microeconomic Impact of Debt Recovery Tribunals in India’

This study uses a micro dataset on project loans to show that the establishment of the new DRTs causes loans with high overdues to improve repayment.[72] The paper notes that tribunals reduced delinquency for the average loan by 28 percent. They also lowered the interest rates charged on larger loans, holding constant borrower quality.

This suggests that the speedier processing of debt recovery suits can lower the cost of credit – that is to say, the establishment of DRTs leads banks to charge lower interest rates on new project loans than it otherwise would have.

Prasanth Regy, Shubho Roy and Renuka Sane, ‘Understanding judicial delays in India: Evidence from Debt Recovery Tribunals’

The authors note that although Debt Recovery Tribunals were set up to wrap up the debt recovery process within 180 days, empirically, judicial delay can be observed in their proceedings as well.[73] They use a novel strategy using micro-data, such as the date and content of orders as well as the factors impacting adjournments, rather than macro-data such as disposal rates, to study the phenomenon of judicial delay.

They find that the average case takes 2.7 years to be disposed off, mostly due to avoidable trial failures and adjournments sought by borrowing parties (petitioners). They explain this by referring to firstly, petitioners’ preference to settle matters outside of court, and secondly the perverse incentives instituted for lawyers who are billed on the basis of hearings. Finally, they note that administrative issues in the tribunal itself may cause delays, and suggest reforms to reduce pendency that target all of these stakeholders.

Pavithra Manivannan, Susan Thomas, and Bhargavi Zaveri Shah, ‘Helping litigants make informed choices in resolving debt disputes’

The authors investigate the factors that they believe would impact litigant decision-making across 3 courts in Bombay, including the Debt Recovery Tribunal.[74] Their study focusses on the following questions:

- How likely is it to get a first hearing in the first year from filing the case in the court?

- How likely is it that the matter will get disposed in the first year from the filing of the case?

- How many hearings are most likely to take place in the first year from the filing of the case?

They conclude that there is a 96% chance that a case filed in the DRT would be heard within a year of its filing, a 17.3% chance of disposal with an average of expected hearings set at 2.7. Their data shows that the DRT performs better in these metrics than the High Court, but worse than another special tribunal, the NCLT.

Renuka Sane, ‘Estimating the Potential Number of Personal Insolvency Cases at the DRT’

This article examines the likely load on DRTs due to the notification of personal insolvency sections of the IBC by asking three questions with respect to personal loans from the banking channel in India[75]:

- What is the spread of personal loans across districts in India?

- How many cases are likely to emerge on account of defaults?

- How well prepared are the DRTs to handle these cases?

It focusses on the number of loan accounts (potential insolvencies) rather than the value of credit outstanding. It notes that districts with a high concentration of loan accounts (barring the seven in the top 20) have DRTs, but it also points out that they shoulder heavy case-loads.

Moreover, it notes and provides suggestions for the potential challenges of including personal insolvencies within the IBC due to the nature of the cases, which is different from ordinary cases at DRTs.

DAKSH, ‘State of Tribunal Report, 2025’

The State of Tribunals in India, 2025 is the first comprehensive effort to map, analyse, and evaluate the functioning of India’s tribunal ecosystem, with a particular focus on commercial tribunals. Tribunals in India were originally envisioned as specialised, quasi-judicial bodies that could resolve disputes more efficiently than traditional courts, combining legal adjudication with sectoral expertise. However, over time, the system has become fragmented, resource-constrained, and beset with structural weaknesses that undermine its promise of swift, credible justice.[76]

By establishing a baseline assessment of tribunal functioning, the report aims to generate evidence, highlight institutional challenges, and provide reform pathways that align with India’s broader economic and governance objectives.

Hiteshkumar Thakkar, Gaurang Rami and Pratik Parashar Sarmah, Efficacy of Debt Recovery Legislation: Indian Experience

Efficacy of Debt Recovery Legislation: An Indian Experience[77] examines India’s attempts to deal with rising non-performing assets (NPAs) through statutory frameworks. The authors analyse the Recovery of Debts Due to Banks and Financial Institutions Act, 1993 and the Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest Act, 2002, as well as the 2016 amendment that sought to close regulatory gaps. Using statistical analysis of Debt Recovery Tribunal (DRT) performance before and after the SARFAESI Act’s enactment, the paper assesses how these laws have affected disposal rates and debt recovery outcomes. It highlights that despite legislative efforts, India has yet to identify an effective mechanism to resolve NPAs; the paper suggests development of a secondary market exchange for distressed assets could improve resolution efficacy.

Ulf von Lilienfeld-Toal, Dilip Mookherjee & Sujata Visaria, The Distributive Impact of Reforms in Credit Enforcement: Evidence From Indian Debt Recovery Tribunals

The paper The Distributive Impact of Reforms in Credit Enforcement: Evidence From Indian Debt Recovery Tribunals analyses how legal reforms that strengthened the enforcement of lender rights in India influenced credit allocation across firms of different sizes and wealth levels. The authors develop a theoretical general equilibrium model showing that when the supply of credit is not perfectly elastic, stronger enforcement can raise interest rates and reallocate credit away from small, less wealthy borrowers to larger, wealthier ones. Using firm-level panel data, they exploit variation in the timing of the establishment of Debt Recovery Tribunals across Indian states as an exogenous reform. Their empirical results show that after DRTs were set up, new long-term borrowing and fixed investment increased for larger firms but declined for smaller firms, and interest rates on borrowing rose for all firms. These findings suggest that, contrary to the conventional belief that stronger enforcement uniformly expands credit access, in contexts of inelastic credit supply, legal enforcement reforms can have adverse distributional effects by constricting access for poorer borrowers while benefiting wealthier ones.[78]

Issues

Pendency of cases has been noted in the research publications above as well as the Supreme Court.[79]

The appointment process has been questioned on the ground of non-independence – it has been argued that the DRT lacks independence because the government nominees in the appointment process may overrule the judicial nominee.[80] Moreover, the Finance Ministry playing a dual role in providing support staff to DRTs and regulating the public sector banks that are the bulk of litigants at DRTs is also a potential cause of concern – i.e., blurring of executive and judicial nature of a tribunal – that has been noted by the Supreme Court.[81]

Moreover, these Tribunals sometimes face administrative issues like a lack of space, electricity and other basic resources due to a lack of support from the Finance Ministry. [82]The lack of manpower, adequate infrastructure and resources was also noted by the Supreme Court, who directed the Union to provide information about remedial steps.[83]

Way Forward

The Finance Ministry is exploring further amendments to the RDBFI Act to solve the problem of pendency and has directed banks and financial institutions to leverage the e-auction platform, currently under development, for listing and auction of properties.[84]

The persistent pendency and institutional challenges faced by Debt Recovery Tribunals indicate the need for a multi-pronged reform strategy. First, capacity constraints must be addressed through timely appointments of Presiding Officers and Recovery Officers, supported by rational staffing norms based on caseload and filing trends. Empirical studies and government reports suggest that without adequate human resources, procedural streamlining alone is insufficient to reduce delays.[85]

Second, concerns regarding the independence of DRTs necessitate reforms in the appointment and administrative oversight framework. Consistent with Supreme Court jurisprudence on tribunal independence, greater judicial primacy in appointments and clearer separation between executive functions and adjudicatory processes would strengthen institutional legitimacy and public confidence.[86]

Third, administrative and infrastructural deficiencies such as lack of space, technological gaps, and inadequate support staff should be remedied through assured budgetary allocations and centralized tribunal administration. The ongoing transition to e-DRT systems provides an opportunity to standardize procedures, improve transparency, and enable data-driven monitoring of tribunal performance.[87]

Finally, systematic collection and publication of case-level data should be institutionalized. Disaggregated data on filings, adjournments, disposal times, and recovery outcomes can inform continuous evaluation of reforms and guide evidence-based policy interventions, ensuring that DRTs fulfil their statutory objective of expeditious and effective debt recovery.[88]

References

- ↑ S.3, Banks and Financial Institutions (RDDBFI) Act, 1993 https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/1775/1/AArecovery1993__51.pdf

- ↑ S. 17 (1) r/w Definition of debt in s. 2 (g), Recovery Of Debts And Bankruptcy Act, 1993

- ↑ Notification S.0. 4312(E), Ministry of Finance Department of Financial Services (06 September 2018) https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/policy/monetary-limit-for-filing-cases-in-drt-doubled-to-rs-20-lakh/articleshow/65706999.cms?from=mdr

- ↑ The Recovery of Debts and Bankruptcy Act, 1993, § 3

- ↑ The Recovery of Debts and Bankruptcy Act, 1993, § 2(o)

- ↑ The Recovery of Debts and Bankruptcy Act, 1993, § 3

- ↑ The Recovery of Debts and Bankruptcy Act, 1993, § 4

- ↑ The Recovery of Debts and Bankruptcy Act, 1993, § 5

- ↑ Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest Act, 2002, § 27 (as amended by Enforcement of Security Interest and Recovery of Debts Laws and Miscellaneous Provisions (Amendment) Act, 2016).

- ↑ Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest Act, 2002, § 27 (as amended by Enforcement of Security Interest and Recovery of Debts Laws and Miscellaneous Provisions (Amendment) Act, 2016).

- ↑ The Recovery of Debts and Bankruptcy Act, 1993, § 6

- ↑ Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest Act, 2002, § 28 (as amended by Enforcement of Security Interest and Recovery of Debts Laws and Miscellaneous Provisions (Amendment) Act, 2016).

- ↑ The Recovery of Debts and Bankruptcy Act, 1993, § 7

- ↑ The Recovery of Debts and Bankruptcy Act, 1993, § 17

- ↑ The Recovery of Debts and Bankruptcy Act, 1993, § 18

- ↑ The Recovery of Debts and Bankruptcy Act, 1993, § 19

- ↑ The Recovery of Debts and Bankruptcy Act, 1993, § 1(4)

- ↑ Government of India, Ministry of Finance, Notification No. S.O. 4312(E), dated 6 Sept. 2018, raising pecuniary jurisdiction of Debts Recovery Tribunals under the Recovery of Debts and Bankruptcy Act, 1993.

- ↑ Debts Recovery Tribunal (Procedure) Rules, 1993, Rule 4

- ↑ Debts Recovery Tribunal (Procedure) Rules, 1993, Rule 5

- ↑ Debts Recovery Tribunal (Procedure) Rules, 1993, Rule 5A

- ↑ Debts Recovery Tribunal (Procedure) Rules, 1993, Rule 18

- ↑ Debts Recovery Tribunals and Debts Recovery Appellate Tribunals Electronic Filing Rules, 2020, Rule 3

- ↑ Debts Recovery Tribunals and Debts Recovery Appellate Tribunals Electronic Filing (Amendment) Rules, 2021, Rule 3 sub rule (2)

- ↑ Debts Recovery Tribunals and Debts Recovery Appellate Tribunals Electronic Filing (Amendment) Rules, 2023, Rule 3 sub rule (2)

- ↑ Debts Recovery Tribunals and Debts Recovery Appellate Tribunals Electronic Filing (Amendment) Rules, 2025, Rule 4

- ↑ The Recovery of Debts and Bankruptcy Act, 1993, § 22

- ↑ Debts Recovery Tribunals and Debts Recovery Appellate Tribunals Electronic Filing Rules, 2020, Rule 5

- ↑ Tiwari Committee, Report of the Committee on Legal and Other Difficulties Faced by Banks and Financial Institutions (1981)

- ↑ Government of India, (1991), Report of the Committee on the Financial System (Chairman: M. Narasimham)

- ↑ Government of India, (1998), Report of the Committee on Banking Sector, (Chairman: M. Narasimham).

- ↑ DBOD No. BP.BC.174/09.06.001/98-99, Letter from RBI, “Working Group to Review the Functioning of DRTs” (1998)

- ↑ Union of India & Anr. vs. Delhi High Court Bar Association & Ors 2002 (4) SCC 275

- ↑ Standard Chartered Bank vs. Dharmendra Bhoi, (2013) 15 SCC 341

- ↑ Debt Recovery Tribunals (India), Organizational Structure, DRT Home (drt.gov.in), https://drt.gov.in/#/organizationalstructure (last visited Nov. 30, 2025)

- ↑ S. 4 (1), RDDBFI Act

- ↑ Debts Recovery Tribunal (Procedure for Appointment as Presiding Officer of the Tribunal) Rules, 1998

- ↑ S.5, RDBFI Act

- ↑ Article 233, Constitution of India

- ↑ S.6 RDBFI Act

- ↑ S. 7 (3), RDBFI Act

- ↑ S.15, RDBFI Act

- ↑ Debt Recovery Tribunal (Procedure) Rules, 1993, https://upload.indiacode.nic.in/showfile?actid=AC_CEN_2_33_00045_199351_1524048948493&type=rule&filename=Debts%20Recovery%20Tribunal%20(Procedure)%20Rules,%201993.pdf

- ↑ S.19, RDBFI Act

- ↑ Debt Recovery Tribunal (Procedure) Rules, 1993, rr. 12(1), 12(6).

- ↑ Recovery of Debts and Bankruptcy Act, 1993, § 19(12).

- ↑ Recovery of Debts and Bankruptcy Act, 1993, § 19(13).

- ↑ Recovery of Debts and Bankruptcy Act, 1993, § 19(20).

- ↑ Recovery of Debts and Bankruptcy Act, 1993, § 19(13A).

- ↑ Recovery of Debts and Bankruptcy Act, 1993, § 19(18).

- ↑ Recovery of Debts and Bankruptcy Act, 1993, § 19(19).

- ↑ Recovery of Debts and Bankruptcy Act, 1993, §§ 25–29.

- ↑ Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest Act, No. 54 of 2002

- ↑ Debt Recovery Tribunals (India), Organizational Structure, DRT — Home (drt.gov.in), https://drt.gov.in/#/organizationalstructure (last visited Nov. 30, 2025)

- ↑ Transcore v. Union of India, AIR 2000 SC 712.

- ↑ Recovery of Debts and Bankruptcy Act, 1993, § 19(1).

- ↑ Recovery of Debts and Bankruptcy Act, 1993, § 1(4), as amended by Recovery of Debts Laws (Amendment) Act, 2016.

- ↑ Recovery of Debts and Bankruptcy Act, 1993, § 30

- ↑ Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest Act, 2002, §§ 13, 17

- ↑ SARFAESI Act, 2002, § 17

- ↑ Recovery of Debts and Bankruptcy Act, 1993, § 19

- ↑ IBC, 2016, Part III

- ↑ IBC, 2016, §§ 78–94

- ↑ Debt Recovery Tribunals, About Us, Gov’t of India, Dep’t of Fin. Servs., Ministry of Fin., https://drt.gov.in/#/aboutus

- ↑ S. 3 (2), RDBFI Act

- ↑ Debt Recovery Tribunals, About Us, Gov’t of India, Dep’t of Fin. Servs., Ministry of Fin., https://drt.gov.in/#/aboutus

- ↑ Government of India, Dep’t of Fin. Servs., Ministry of Fin., e-DRT User Manual, https://drt.etribunals.gov.in/edrt/user_manual.pdf

- ↑ Debt Recovery Tribunal, Public Notice (2024),https://cis.drt.gov.in/drtlive/pdf/pdf.php?file=L3VwbG9hZHMvZHJ0L3B1YmxpY25vdGljZS8yMDI0LzUzNmU2NmU4ZTMzOGJiYzQyMDhkM2MyNGVjYWVjNmY0XzUzNmU2NmU4ZTMzOGJiYzQyMDhkM2MyNGVjYWVjNmY0LnBkZioqKjMjMTg1ODY=

- ↑ Government of India, Ministry of Fin., Dep’t of Fin. Servs., Annual Report 2022–23 (2023),https://financialservices.gov.in/beta/sites/default/files/2023-09/DFS-Annual-report-2022-23-Eng.pdf

- ↑ Mukund P. Unni, A Study on the Effectiveness of Remedies Available for Banks in a Debt Recovery Tribunal (Ctr. for Pub. Pol’y Rsch., Working Paper),http://www.digitalrtimission.com/cppr/A%20STUDY%20ON%20THE%20EFFECTIVENESS%20OF%20REMEDIES%20AVAILABLE-Mukund.pdf

- ↑ CUTS Ctr. for Competition, Inv. & Econ. Regulation, Consolidated Research Report on Regulatory Impact Assessment in the Indian Financial Sector, https://cuts-ccier.org/pdf/Publications-Consolidated_Research_Report.pdf

- ↑ Sujata Visaria, Legal Reform and Loan Repayment: The Microeconomic Impact of Debt Recovery Tribunals in India, 57 J. Dev. Econ. 1 (2009), https://www.jstor.org/stable/25760171

- ↑ Prasanth Regy, Shubho Roy & Renuka Sane, Understanding Judicial Delays in India, Leap Journal (May 18, 2016),https://blog.theleapjournal.org/2016/05/understanding-judicial-delays-in-india.html#gsc.tab=0

- ↑ Pavithra Manivannan, Susan Thomas & Bhargavi Zaveri Shah, Helping Litigants Make Informed Choices in Resolving Debt Disputes, Leap Journal (June 5, 2023)https://blog.theleapjournal.org/2023/06/helping-litigants-make-informed-choices.html#gsc.tab=0

- ↑ https://blog.theleapjournal.org/2017/12/estimating-potential-number-of-personal.html#gsc.tab=0

- ↑ Singh, R., & Prakash, S. B. S. (Eds.). (2025). State of Tribunals Report. DAKSH.

- ↑ Hiteshkumar Thakkar, Gaurang Rami & Pratik Parashar Sarmah, Efficacy of Debt Recovery Legislation: An Indian Experience, 62 Artha Vijnana 38 (2020).

- ↑ Ulf von Lilienfeld-Toal, Dilip Mookherjee & Sujata Visaria, The Distributive Impact of Reforms in Credit Enforcement: Evidence From Indian Debt Recovery Tribunals, 80 Econometrica 497 (2012).

- ↑ Centre for Public Interest Litigation vs. Housing and Urban Development 2017 (3) SCC 566

- ↑ https://scroll.in/article/830511/indias-banking-crisis-is-made-worse-by-the-poor-performance-of-its-debt-recovery-tribunals

- ↑ L. Chandra Kumar v. Union of India AIR 1997 SC 1125

- ↑ http://indiatoday.intoday.in/story/poor-infrastructure-drt-new-delhi-finance-ministry/1/788534.html

- ↑ Centre for Public Interest Litigation vs. Housing and Urban Development 2017 (3) SCC 566

- ↑ https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/money-and-banking/finance-ministry-explores-amendments-in-sarfaesi-and-drt-acts-for-swift-debt-recovery/article67860189.ece

- ↑ Sujata Visaria, Legal Reform and Loan Repayment: The Microeconomic Impact of Debt Recovery Tribunals in India, 57 J. Dev. Econ. 1 (2009).

- ↑ Government of India, Ministry of Fin., Dep’t of Fin. Servs., Annual Report 2022–23 (2023)

- ↑ Government of India, Dep’t of Fin. Servs., Ministry of Fin., e-DRT User Manual, https://drt.etribunals.gov.in/edrt/user_manual.pdf

- ↑ Prasanth Regy, Shubho Roy & Renuka Sane, Understanding Judicial Delays in India, Leap Journal (May 18, 2016), https://blog.theleapjournal.org/2016/05/understanding-judicial-delays-in-india.html.