Debt recovery appellate tribunal

What is 'Debt Recovery Appellate Tribunal'

The Debt Recovery Appellate Tribunal (DRAT) serves as the appellate authority for decisions rendered by the Debt Recovery Tribunals (DRTs) in India, established under the Recovery of Debts and Bankruptcy Act, 1993 (RDB Act) to ensure expeditious adjudication and recovery of debts owed to banks and financial institutions.[1]

Its primary function is to ensure that appeals against DRT orders are addressed efficiently, thereby maintaining the integrity and effectiveness of the debt recovery process. The tribunal acts as a crucial second-tier forum in India's specialized debt recovery mechanism, providing appellate oversight and ensuring procedural fairness in financial recovery proceedings.

The (DRAT) has the power to affirm, modify, or set aside decisions of DRT on legal grounds. It may grant stays on recovery, provide interim relief, and re-examine evidence and arguments before DRT to ensure legal and procedural correctness. The DRAT can also reduce the mandatory 50% pre-deposit to as low as 25% in deserving cases. Its decisions are final and binding, subject only to limited judicial review by the High Court.

DRAT plays a pivotal role in facilitating speedy dispute resolution, reinforcing the strength of the banking and financial sector, balancing creditor–borrower interests, complementing the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC), and promoting legal certainty through consistent precedents.[2]

Official Definition of 'Debt Recovery Appellate Tribunal'

'Debt Recovery Appellate Tribunal' as defined or established in legislations

The Recovery of Debts and Bankruptcy Act, 1993

Under Section 8[3] of the Recovery of Debts and Bankruptcy Act (RDBA), 1993,

8(1)The Central Government shall, by notification, establish one or more Appellate Tribunals, to be known as the Debts Recovery Appellate Tribunal, to exercise the jurisdiction, powers and authority conferred on such Tribunal by or under this Act:

Provided that the Central Government may authorise the Chairperson of any other Appellate Tribunal, established under any other law for the time being in force, to discharge the functions of the Chairperson of the Debts Recovery Appellate Tribunal under this Act in addition to his being the Chairperson of that Appellate Tribunal.[4]

(1A) The Central Government shall, by notification, establish such number of Debt Recovery Appellate Tribunals to exercise jurisdiction, powers and authority to entertain appeal against the order made by the Adjudicating Authority under Part III of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016 (31 of 2016).[5]

(2) The Central Government shall also specify in the notification, referred to in sub-section (1) the Tribunals in relation to which the Appellate Tribunal may exercise jurisdiction.

(3) Notwithstanding anything contained in sub-sections (1) and (2), the Central Government may authorise the Chairperson of one Appellate Tribunal to discharge also the functions of the Chairperson of other Appellate Tribunal.[6]

Legal provision(s) relating to 'Debt Recovery Appellate Tribunal'

Enabling Act(s)

The central government under the Recovery of Debts and Bankruptcy Act (RDBA), 1993 constitutes the DRAT by the powers vested in it under section 8 of the said act.

It is worthy to note that the above section was amended on account of various other Acts, namely,

- S.29 of The Enforcement Of Security Interest And Recovery Of Debts Laws And Miscellaneous Provisions (Amendment) Act, 2016[4] (Amendment to SARFAESI Act, 2002 and RDBA, 2003);

- S.249 of The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016 (Part V)[5];

- S.5 of The Recovery Of Debts Due To Banks And Financial Institutions (Amendment) Act, 2000[6]

DRAT functions as the appellate authority in cases as may be mentioned in all the above mentioned Acts.

Jurisdiction (Appeal to the Appellate Tribunal)

Constitutional:

Per section 20(1&2)[7] of the RDB Act, a person aggrieved by an order of a Tribunal under the Act (DRT) may appeal to the Appellate Tribunal, unless the order was made with the consent of all parties. Section 20(4) also provides for cases appealed to it under s.181(1) of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016 (31 of 2016).

Under section 181(1)[8] of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016, an appeal against a Debt Recovery Tribunal order must be filed before the Debt Recovery Appellate Tribunal within 30 days. The Appellate Tribunal may allow an additional maximum of 15 days for filing if it is satisfied that there was sufficient cause for the delay.

Section 18[9] of the The Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest Act, 2002 provides that: any person aggrieved by a Debt Recovery Tribunal order under Section 17 may appeal to the Appellate Tribunal within 30 days, with the prescribed fee (which may differ for borrowers and others). A borrower’s appeal will not be entertained unless they first deposit 50% of the debt due (as claimed by the secured creditor or determined by the DRT, whichever is less). The Appellate Tribunal may reduce this deposit to not less than 25%, with written reasons. Appeals are to be disposed of in accordance with the provisions and rules of the Recovery of Debts Due to Banks and Financial Institutions Act, 1993.

Geographical:

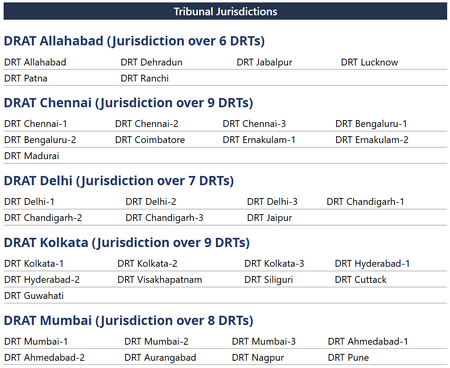

There are 39 DRTs and 5 DRATs, which are single member Tribunals. The jurisdiction of DRATs and list of DRTs is as below:

Authority framework

By virtue of Section 9[10] of the RDB Act, the Appellate Tribunal is composed of a single member, called the Chairperson, who is appointed by the Central Government through a notification.

Provisions relating to the Chairperson

Section 15A[11] of RDB Act refers to the Tribunals Reforms Act (TRA), 2021[12] for the purpose of appointment, tenure, salary, resignation, removal and terms of service. Chapter II of the Tribunals Reforms Act, 2021 deals with the "Conditions of Service of Chairperson and Members of Tribunal". The Central Government can make rules regarding qualifications, appointment, salaries, allowances, resignation, removal, and other service conditions of tribunal Chairpersons and Members

Appointment

Tribunal members are appointed by the Central Government by notification, as mentioned above under section 8[3] of RDB Act.

Section 3[13] of The Tribunals Reforms Act lays down qualifications, appointment, etc., of Chairperson and Members of Tribunal, with a minimum age requirement of 50 years for appointment. Appointments are made by the Central Government based on recommendations from a Search-cum-Selection Committee, who determine the procedure for making the recommendations. The composition of the committee includes: Chief Justice of India or a Supreme Court Judge (as Chairperson with casting vote); Two Government Secretaries nominated by the Central Government; The outgoing Chairperson or a retired SC/HC Judge; and The concerned Ministry Secretary (Member-Secretary without voting rights). The Committee recommends a panel of two names, and the Central Government must decide preferably within three months.

Reappointment

In accordance with section 11[14] of RDB act, a chairperson is eligible for reappointment.

Per Section 6[15] of the Tribunals Reforms Act, The Chairperson and Members of a Tribunal can be re-appointed under the Act, with preference given to their prior service, and all re-appointments must follow the same procedure as the original appointment under Section 3(2).

Qualifications

Section 10[16] of the RDB Act defines the qualifications for appointment as Chairperson of the Appellate Tribunal: A person shall not be qualified for appointment as the Chairperson of an Appellate Tribunal unless he— (a) is, or has been, or is qualified to be, a Judge of a High Court; or (b) has been a member of the Indian Legal Service and has held a post in Grade I of that service for at least three years; or (c) has held office as the Presiding Officer of a Tribunal for at least three years.

As mentioned above, section 3 of Tribunals Reforms Act lays down minimum age requirement as 50 years.

Tenure

The Chairperson of an Appellate Tribunal serves a five-year term, may be reappointed, but cannot continue in office after reaching the age of seventy, per section 11[17] of RDB Act.

However, per section 5[18] of Tribunals Reforms Act, 2021, Chairpersons hold office for four years or until age 70, whichever is earlier. By the powers vested through section 15A of the RDB Act, this provision prevails.

Salary /Allowances

In accordance with section 13[19] of RDB Act and section 7[20] of Tribunals Reforms Act, the Central Government makes rules for salaries, and Members receive allowances equivalent to Central Government officers holding posts with the same pay, with special provisions for higher house rent reimbursement under certain conditions. Service conditions cannot be varied to the disadvantage of the Chairperson after appointment per provisions of RDB Act and TRA.

Vacancies

To be filled by Central government by notification in accordance with the provisions of the Act per section 14[21] of RDB Act

Resignation/Removal

Per section 15[22] of RDB Act, the Chairperson of an Appellate Tribunal may resign by giving written notice to the Central Government, but must continue in office for three months, until a successor assumes charge, or until their term ends, whichever is earlier, unless the Government allows an earlier relinquishment.

They cannot be removed except by the Central Government on grounds of proved misbehavior or incapacity after an inquiry conducted by a Supreme Court judge. The officer must be informed of charges and given a reasonable opportunity to be heard. During the inquiry, the Central Government may suspend the officer if necessary, after consulting the Selection Committee Chairperson. The Central Government may also make rules to regulate the procedure for investigating misbehavior or incapacity.

Pursuant to section 4[23] of the Tribunals Reforms Act, the Central Government, on the recommendation of the Committee, may remove a Chairperson or Member if they are adjudged insolvent, convicted of an offence involving moral turpitude, become physically or mentally incapable of performing their duties, acquire financial or other interests likely to affect their functions, or abuse their position in a manner prejudicial to the public interest; for the last three grounds, the officer must be informed of the charges and given an opportunity to be heard before removal.

Powers

Section 17A[24] was inserted in the act by an amendment in 2000. The Chairperson of an Appellate Tribunal exercises general superintendence and control over the Tribunals under their jurisdiction, including appraising work and recording annual confidential reports of Presiding Officers. To exercise these powers, the Chairperson may direct Tribunals to provide information on pending and disposed cases, convene periodic meetings of Presiding Officers to review performance, and, if necessary, recommend inquiry to the Central Government against a Presiding Officer for misbehavior or incapacity, with reasons recorded in writing. Additionally, the Chairperson may, on application or on their own motion, transfer cases from one Tribunal to another after notice and hearing of the parties.

Bar of jurisdiction

Section 18[25] of the RDB Act bars the jurisdiction of any civil court or authority for recovery of debt, except High Court and Supreme Court in the exercise of their writ jurisdiction under Article 226 and 227 of the Constitution of India.

Procedure for appeal

Per section 20[7] of the RDB Act, appeals (including those under Section 181(1) of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016) must be filed within 30 days of receiving the order, in the prescribed form with the required fee, though the Tribunal may allow a delayed appeal for sufficient cause. The Appellate Tribunal, after giving parties a chance to be heard, may confirm, modify, or set aside the challenged order and must send copies of its decision to the parties and the concerned Tribunal. Appeals should be handled expeditiously, with an effort to dispose of them within six months.

Further procedures for appeals are governed by 'The Debts Recovery Appellate Tribunal (Procedure) Rules, 1994'[26], procedure for appeals before DRAT are as follows:

Filing appeals

Rule 5 - A memorandum of appeal must be submitted in the prescribed form either in person or by registered post to the Registrar of the Appellate Tribunal having jurisdiction (Rule 7). If the appellant is a bank or financial institution, the appeal may be presented by authorized legal practitioners or officers acting as Presenting Officers; otherwise, it may be presented by the appellant in person, through an agent, or by a duly authorized legal practitioner. An appeal sent by post is deemed presented on the date it is received by the Registrar. The appeal must be submitted in four sets in a paper book, along with empty envelopes addressed to the respondent(s), with additional sets and envelopes provided if there are multiple respondents. The appeal, reference, application, representation, document or other matters must be in either English/Hindi languages and in case of any other language, it should be accompanied by a true copy of translation in English or Hindi according to Rule 4. A memorandum of appeal may request only one cause of action, unless the additional reliefs sought are directly consequential to that primary cause per Rule 12.

Presentation and Scrutiny

Rule 6 - The Registrar must endorse the date an appeal is presented and sign it. On scrutiny, if the appeal is in order, it is registered and given a serial number. If defects are found, formal defects may be corrected in the Registrar’s presence, while other defects may be rectified within a time allowed by the Registrar. If the appellant fails to correct defects in time, the Registrar may refuse registration with reasons recorded in writing. An appeal against the Registrar’s refusal can be made within 15 days to the Chairperson, whose decision is final.

Rule 6A - A party aggrieved by an Appellate Tribunal order due to a mistake or apparent error may apply for a review to the same Tribunal within 30 days of the order, accompanied by an affidavit. The Tribunal may reject the application if no sufficient grounds exist or allow the review if satisfied with the grounds, but only after giving the opposite party notice and an opportunity to be heard.

Fees and Deposits

Rule 8 - Every memorandum of appeal under Section 20 must be accompanied by a prescribed fee, which can be paid either by a crossed demand draft drawn on a nationalised bank in favor of the Registrar or via a crossed Indian Postal Order payable at the Central Post Office of the station where the Appellate Tribunal is located. Filing fees range from Rs. 12,000 to Rs. 30,000 depending on debt amount. Per section 21 and Rule 9, appellants (other than banks/financial institutions) must deposit fifty percent of the debt determined by the Tribunal, which may be reduced to twenty-five percent minimum for recorded reasons.

Section 21[27] of the RDB Act provides that where the appeal is being preferred by the debtor, who as per the order of DRT is liable to pay money to bank or financial institution at the time of filing appeal is required to deposit before DRAT 50% of the amount he is required to pay as per the order of the DRT. However with the permission of DRAT, this amount can be reduced by DRAT, but reduced amount should not be below 25% of the debt amount.

Contents and documents of the appeal

Rule 10: A memorandum of appeal must clearly list the grounds of appeal under separate, numbered headings, without arguments or narrative, and typed double-spaced on one side of the paper. A separate appeal is not required for seeking an interim order if the request is included in the main memorandum of appeal.

Rule 11: A memorandum of appeal must be filed in triplicate and accompanied by two copies of the order being appealed, with at least one being a certified copy. If a party is represented by an agent, authorization documents must be attached; if represented by a legal practitioner, a duly executed Vakalatnama is required. When a bank or financial institution is represented by one of its officers as a presenting officer, the relevant authorization documents must also be included.

Regarding respondents

The Registrar must serve each respondent a copy of the memorandum of appeal and paper book by registered post per Rule 13.

Rule 14: A respondent must file four sets of their reply and supporting documents within one month of receiving notice of the appeal and must also provide a copy to the appellant. The Appellate Tribunal may permit a late filing of the reply at its discretion upon the respondent’s request.

Rule 15: If someone other than a bank or financial institution files an appeal, the bank or financial institution seeking recovery under Section 19 must be made the respondent. Conversely, if a bank or financial institution files the appeal, the opposite party becomes the respondent.

Hearing and orders

Rule 16 - The Appellate Tribunal must inform the parties of the date and place of the appeal hearing in the manner directed by the Chairperson through general or special orders.

Rule 18 - Every order of the Appellate Tribunal must be written, signed, and dated by the Chairperson, and it must be pronounced in open court.

Rule 19 - The Appellate Tribunal may release selected orders for publication in authoritative reports or the press on terms it decides.

Rule 20 - Every order on an appeal must be communicated free of cost to the appellant, the respondent, and the concerned Tribunal, either in person or by registered post.

Rule 21 - A party inspecting records of a pending appeal is charged ₹20 per hour (minimum ₹100). For copies, a fee of ₹5 per folio applies for plain documents, and ₹10 per folio if typing of statements or figures is involved.

Rule 22 - The Appellate Tribunal may issue any orders or directions necessary to enforce its decisions, prevent abuse of its process, or ensure justice.

Powers of the Registrar

Rules 25 and 26 - The Registrar of the Appellate Tribunal is responsible for the custody of its records and official seal and performs functions assigned under the rules or by the Chairperson. The seal cannot be affixed to orders, processes, or certified copies without the Registrar’s written authorization. Subject to the Chairperson’s directions, the Registrar has additional powers including receiving appeals and documents, scrutinizing and registering appeals, requiring amendments, fixing hearing dates, issuing notices, directing formal amendments, granting copies or inspection of records, managing service of notices, and requisitioning records from other authorities.

DRAT as defined in Case law(s)

Standard Chartered Bank v. Dharmender Bhohi discussing jurisdiction

The Supreme Court dealt with an instance where the DRAT, apart from deciding the appeal, had also allowed the auction purchaser liberty to pursue action against the Bank for any omission. The Supreme Court held that the DRAT is empowered to exercise jurisdiction only over matters falling within its statutory domain, and it cannot grant remedies outside that scope. The Court reaffirmed that the DRAT, being a creature of statute, does not possess inherent powers. [28]

M/s Sidha Neelkanth Paper Industries Private Limited v. Prudent ARC Limited discussing pre-deposit amount calculation

Supreme Court clarified how this pre-deposit amount is to be calculated. The Court held that in order to satisfy the pre-deposit requirement under Section 18, an appellant has to deposit 50% of the debt due, along with interest as claimed by the bank in the notice under Section 13(2) of the 2002 Act. The Court relied on the definition of “debt” i.e., liability inclusive of interest, under Section 2(ha) of the 2002 Act, read with Section 2(g) of the RDB Act, 1993, to arrive at this conclusion. It was further held that where an auction is under challenge, a borrower cannot claim adjustment of the amount realised from the sale of secured properties and deposited by the auction purchaser towards the mandatory pre-deposit.[29]

International Experience

While the concept of specialized debt recovery tribunals exists in various jurisdictions, the specific model of DRAT as established under Indian law is unique to India's legal framework. International debt recovery mechanisms vary significantly between countries, with many nations having bilateral agreements facilitating legal cooperation including debt collection, though practical enforcement still presents challenges. Below is a summary of equivalents and related processes in other countries.

United States

In the United States, the U.S. Bankruptcy Courts function as specialised federal forums for both business and consumer insolvency matters, handling proceedings under Chapters 7, 11, 13 and related creditor-recovery mechanisms. Appeals from these courts are heard either by a Bankruptcy Appellate Panel (BAP)—where authorised within a circuit—or by the U.S. District Court, with further appellate review available before the U.S. Court of Appeals. The overall framework governing these proceedings derives from the U.S. Bankruptcy Code and the Federal Rules of Bankruptcy Procedure. In practice, creditors pursue recovery either through bankruptcy filings, which offer a collective, priority-based distribution mechanism, or through non-bankruptcy remedies available in state courts, depending on the nature of the claim and strategic considerations.[30]

United kingdom

In England and Wales, insolvency matters are heard at first instance by the County Courts exercising insolvency jurisdiction, while more substantial or complex corporate cases fall within the High Court, particularly the Chancery Division and the Business & Property Courts’ specialist insolvency lists. Appeals from County Court or High Court insolvency decisions proceed to the Court of Appeal (Civil Division), and, where permission is granted, may be taken further to the Supreme Court. The procedural framework is shaped by statutory insolvency legislation, the Civil Procedure Rules, and detailed guidance set out in the Insolvency Practice Direction and related practice directions, which govern core processes such as service requirements, petitions, and winding-up procedures.[31]

European Union

Within the European Union, there is no unified insolvency tribunal akin to a “DRT,” as insolvency remains primarily a national competence; however, cross-border coordination is governed by Regulation (EU) 2015/848 (the Recast Insolvency Regulation), supported by EU instruments such as the European Order for Payment and the European Enforcement Order, which facilitate recognition and enforcement of cross-border debt claims. Each Member State maintains its own first-instance insolvency courts—for example, Germany’s Insolvenzgerichte (local courts with insolvency chambers) and France’s Tribunaux de commerce for corporate insolvency—with appeals handled through domestic appellate structures. The EU Insolvency Regulation ensures mutual recognition of proceedings, determines jurisdiction, and provides rules for cooperation between national courts and insolvency practitioners across Member States.[32]

Australia

In Australia, insolvency operates under a federal framework in which the Australian Financial Security Authority (AFSA) serves as the administrative and registry body for personal bankruptcy, including the administration of notices, registers, and trustee appointments. Court-based applications—such as creditor’s petitions in personal bankruptcy or proceedings relating to corporate insolvency, administration, or winding up—are heard at first instance by the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia or, in certain matters, the Federal Court of Australia. Appeals from the Federal Circuit Court lie to the Federal Court (or its Full Court, where appropriate), with further appeal to the High Court of Australia, subject to special leave. Creditors may initiate bankruptcy proceedings or pursue corporate insolvency remedies through these federal courts, while AFSA facilitates the administrative processes that support personal insolvency administration.[33]

Singapore

Singapore’s insolvency framework is consolidated under the Insolvency, Restructuring and Dissolution Act (IRDA) 2018, under which personal and corporate insolvency proceedings fall within the jurisdiction of the General Division of the High Court, while the Insolvency Office and the Official Assignee administer personal bankruptcy matters. Appeals from High Court insolvency decisions are heard by the Court of Appeal, Singapore’s apex court, and administrative acts of the Official Assignee are subject to defined judicial review and appellate pathways. The IRDA integrates restructuring, corporate insolvency, and personal bankruptcy regimes, with the Official Assignee empowered to act as trustee where required, and filings and applications are primarily made through Singapore’s electronic court filing system, eLitigation.[34]

Japan

In Japan, in-court insolvency proceedings are administered by the District Courts, which serve as the first-instance specialised forums for statutory procedures such as Bankruptcy (hasan), Civil Rehabilitation (minji saisei), and Corporate Reorganization (kaisha kosei), each governed by its respective legislation—the Bankruptcy Law, Civil Rehabilitation Act, and Corporate Reorganization Act. Appeals from insolvency decisions follow the ordinary judicial hierarchy, progressing to the High Courts and, where permitted, to the Supreme Court of Japan. Japanese insolvency law distinguishes between liquidation procedures (including bankruptcy and special liquidation) and restructuring mechanisms (civil rehabilitation and corporate reorganization), with creditor voting thresholds and court confirmation of plans forming core elements of the rehabilitation and reorganization frameworks.[35]

Canada

Canada’s insolvency regime operates under a federal legislative framework comprising the Bankruptcy and Insolvency Act (BIA) and the Companies’ Creditors Arrangement Act (CCAA), with regulatory oversight and practitioner administration carried out by the Office of the Superintendent of Bankruptcy (OSB). Insolvency proceedings themselves are adjudicated by the provincial Superior Courts—such as the Superior Court or Court of King’s Bench—which exercise jurisdiction over bankruptcies, proposals, and restructurings under the BIA, as well as complex corporate reorganizations under the CCAA. Appeals from these Superior Court decisions lie to the respective provincial Court of Appeal, with further recourse to the Supreme Court of Canada subject to leave. The BIA governs trustee licensing, proposals, bankruptcies, and related procedural requirements, while the CCAA provides a flexible, court-supervised framework for large corporate restructurings; the OSB supports these systems through public registers, regulatory guidance, and supervision of insolvency professionals.[36]

Technological transformation and Initiatives

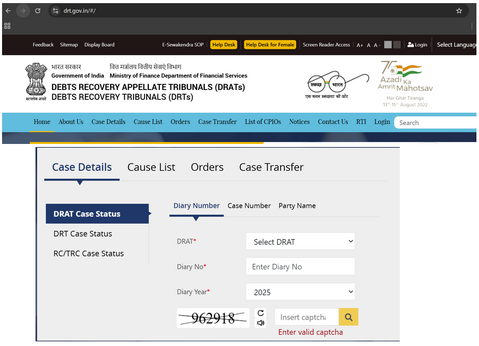

e-DRT Portal

The e-DRT Portal was launched in 2017 as part of the government's Digital India initiative This portal enables online filing of cases, tracking of case status, and digital payment of fees. Under the amended rules (Debts Recovery Tribunals and Debts Recovery Appellate Tribunals Electronic Filing (Amendment) Rules, 2025[37]) effective from 23 June 2025, all pleadings before DRTs & DRATs must be submitted electronically via this platform. The portal supports registration of original applications, securitisation applications, document filing / court fee payment, etc.

Online Recovery Certificate Tracking System

DFS Circular on Online Recovery Certificate Tracking System was issued in 2018 to enable transparent tracking of recovery certificates issued by DRTs. A Recovery Certificate in the DRT/DRAT framework is issued once the Tribunal adjudicates the debt and finalizes the amount payable. As reflected in the e-DRT workflow (drt.gov.in), the certificate is generated after completion of all filings and judicial determination. It serves as the foundational instrument for initiating and executing recovery proceedings before the Recovery Officer.

Digital Case Management

The Department of Financial Services has implemented comprehensive digital case management systems across all DRATs to improve efficiency and reduce pendency. Digital Case Management in the DRAT is an end-to-end electronic system, implemented through the national e-DRT/e-Tribunals platform, that enables fully online filing, scrutiny, processing, tracking, and disposal of appellate matters. Appeals, applications, documents, and fees are filed digitally; scrutiny and defect-rectification are handled electronically; and cases flow seamlessly through automated workflows to the Chairperson. The system provides real-time case status, auto-generated cause lists, digitally signed orders, and a complete electronic record of proceedings, while ensuring uniformity, transparency, and faster disposal across all DRAT benches. DRAT orders are electronically transmitted to DRTs and recovery mechanisms for compliance, supporting integrated, paperless adjudication under DFS’s e-governance framework.[38][39]

Appearance of 'Debt Recovery Appellate Tribunal' in Database

Official Database

Department of Financial Services Portal

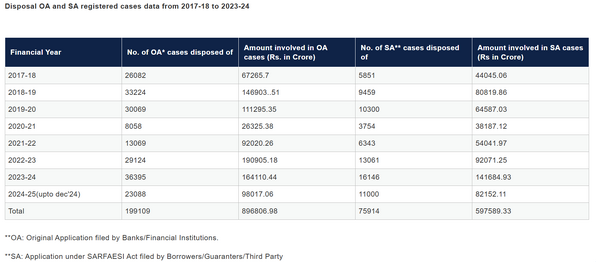

The Department of Financial Services website maintains updated statistics on DRAT functioning, including disposal rates and pendency figures.[40]

Non-Official database

DAKSH

The report[41] examines the functioning of India’s Debts Recovery Appellate Tribunals (DRATs), the statutory appellate bodies under the RDB Act, 1993, which currently comprise five benches supervising 39 DRTs nationwide. This limited distribution creates regional access barriers, especially as the Delhi DRAT handles a disproportionately large jurisdiction. The report outlines the DRAT’s organisational structure, powers, and evolving member qualification rules, noting that as of August 2025 all five Chairpersons are former High Court judges, with an average age of 65.8 years. Staffing data from the Delhi Bench—based on an RTI response—show 16 total staff, of which 75% are permanent. Supreme Court jurisprudence is summarised, including rulings that restrict DRAT’s jurisdiction to statutory limits and reaffirm the mandatory 50% pre-deposit (inclusive of interest) for appeals under SARFAESI. A key finding is the absence of publicly available data on DRAT case pendency or disposal, despite MIS systems being referenced in government reports. The gap analysis highlights systemic challenges, including 2.15 lakh pending cases before DRTs (as of January 2024) and the constraints of single-member benches, recommending expanded staffing, more benches, improved case management, and public reporting of performance metrics.

Research that engages with 'Debt Recovery Appellate Tribunal'

Debt Recovery Tribunals & Recovery of Debt Due to Banks and Financial Institutions

The paper by Naman Jain titled 'Debt Recovery Tribunals & Recovery of Debt Due to Banks and Financial Institutions' reviews India’s institutional framework for debt recovery, focusing on Debt Recovery Tribunals (DRTs) and the Debt Recovery Appellate Tribunals (DRATs) as established under the RDDBFI Act, along with subsequent reforms such as SARFAESI. It evaluates whether these bodies have delivered speedy and effective recovery for banks and financial institutions and explores the gaps that persist. The author argues that despite reforms, stakeholders — notably the RBI and industry players — remain dissatisfied with DRT performance. The analysis shows that despite multiple reforms, both DRTs and DRATs continue to face structural, procedural, and capacity-related shortcomings, leading to persistent dissatisfaction among lenders and the RBI. The author concludes that India’s debt-recovery architecture—including its appellate mechanism (DRAT)—requires comprehensive review and systemic reform to meet its intended objectives.[42]

Debt Recovery Tribunals in India: The Legal Framework

In this paper, authors Mukesh Dwivedi and Aqa Raza explore two primary objectives: first, to examine how Debt Recovery Tribunals (DRTs) function; and second, to analyze the legal statutes governing them. It provides a detailed doctrinal account of the Recovery of Debts Due to Banks and Financial Institutions Act (the DRT Act), including the role of the Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest (SARFAESI) Act and its relationship to non-performing assets. The paper also explores how the Debt Recovery Appellate Tribunals (DRATs) operate as the appellate mechanism over DRTs. Through judicial precedents, statutory interpretation, and procedural analysis, the authors assess key issues such as jurisdiction, powers of tribunals, review mechanisms, and enforcement. The study concludes by highlighting structural and procedural challenges in the DRT/DRAT framework and suggests that reforms are needed for more effective debt recovery in India. [43]

DAKSH — State of Tribunals Report (2025)

The report 'State of Tribunals Report' is DAKSH’s first comprehensive baseline assessment of India’s major commercial tribunals, covering ten bodies including the Debt Recovery Tribunal (DRT) and the Debt Recovery Appellate Tribunal (DRAT). Drawing on data analysis, legal research, and stakeholder consultations, it maps institutional, procedural, and governance challenges undermining tribunal performance. Among key problems identified are chronic vacancies, over-reliance on contractual staff, jurisdictional overlaps, and weak domain expertise. In the case of DRT/DRAT, the report highlights a very large pendency (DRT has over 215,000 pending cases), with more than 86% of DRT cases older than six months — well beyond statutory timelines. It also points to poor physical and digital infrastructure, limited e-filing or hybrid hearings in some tribunals, inconsistent funding, and weak independence due to executive control. Economically, DAKSH estimates that ₹24.72 lakh crore (about 7.48% of India’s GDP) is locked in commercial disputes across tribunals. To address these systemic barriers, the report recommends reforms such as strengthening institutional capacity, improving expertise, filling sanctioned strength, modernising via digitalisation, enhancing transparency, and reducing dependence on temporary staff. By positioning tribunals as central to economic governance, the authors argue for reform as a strategic priority to improve access to justice, investor confidence, and contract enforcement.[41]

E-governance in Debts Recovery Tribunals and Debts Recovery Appellate Tribunals: A Framework for Implementation in India

This paper by S. K. Katara & N. Shastri examines the procedural and operational challenges faced by India’s Debt Recovery Tribunals (DRTs) and their appellate counterpart, the Debt Recovery Appellate Tribunals (DRATs), and proposes an e-governance framework to modernise their core functioning. The authors analyse existing workflows, identify inefficiencies (such as manual case record-keeping, paper-based pleadings, lack of real-time tracking, and weak interconnectivity), and design a technology-enabled model to streamline tribunal processes. The proposed system includes components for online case filing, digital document management, electronic payment of fees, automated notifications, and workflow tracking. The framework also recommends institutional measures—such as capacity building, ICT infrastructure, and change management—to ensure successful implementation. By leveraging ICT, the paper argues, DRTs and DRATs can significantly improve accessibility, transparency, efficiency, and speed of debt recovery adjudication.[44]

Challenges

Below are some broad concerns related to DRATs[45]

Infrastructure and Vacancy Issues

At present, 39 Debts Recovery Tribunals (DRTs) and 5 Debts Recovery Appellate Tribunals (DRATs) are functioning across the country. There need to be more DRTs and DRATs established in the country to handle the growing workload.

Pendency and Delay

One of the significant issues with the (DRT) and DRAT is a large number of pendency, backlogs and slow resolution of cases . District courts saw a sharp overall increase of 13.45 per cent in the pendency of cases between 31 December 2019 and 31 December 2020. Limited number of DRATs add to this issue. Frequent presiding-officer vacancies in DRATs stall appeals for months, severely undermining appellate efficiency and certainty for parties.

Procedural Complexities

The interaction between the RDDBFI Act and other legal frameworks creates complexities including SARFAESI Act overlap where banks often pursue parallel proceedings under both laws. The IBC’s introduction has created jurisdictional overlaps between DRTs, DRATs, and NCLT, causing conflicting rulings and delays in debt recovery.

Limited Geographical Coverage

Debt recovery tribunals are set up in 39 places and The debt recovery appellate tribunals (DRAT) are based in 5 places, in India, they are; Mumbai, Delhi, Kolkata, Allahabad, and Chennai. This limited coverage creates accessibility issues for litigants in remote areas.

Pre-deposit Requirements

Appellants must deposit 50% of the debt amount determined by the DRT before the DRAT hears the appeal. However, the tribunal has discretion to reduce this deposit to 25% in justified cases. This requirement can be burdensome for genuine appellants.

Digital infrastructure gaps

Weak and inconsistent digital systems across DRATs hinder effective e-filing, case tracking, and transparent online case management.

Enforcement of DRAT Orders

Enforcement of DRAT decisions is often delayed as parties frequently pursue parallel writ proceedings before High Courts, prolonging final dispute resolution.

Way Ahead

A stronger and more efficient DRT–DRAT ecosystem requires coordinated improvements across technology, infrastructure, human resources, and legislative design. The following “Way Ahead” outlines key reforms needed to modernize tribunal functioning and ensure faster, more reliable debt recovery.[46]

Technology Integration

The e-DRT initiative seeks to digitize filing, processing, and hearing. Further integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning could help in case management and reducing pendency.

Infrastructure Enhancement

Till date, ₹8,709.77 crore has been released for development of infrastructure facilities for judiciary since the inception of the Centrally Sponsored Scheme (CSS) in 1993-94. The CSS Scheme has been extended till 2025-26 at a total cost of ₹9,000 crore, out of which the central share will be ₹5,307 crore.[47]

Capacity Building

Indian Institute of Banking and Finance has developed Training Module for Presiding Officers in 2021. Regular training programs for Chairpersons and support staff are essential.

Legislative Reforms

The amended act empowers the Central Government to establish a uniform procedure for all the DRTs and DRATs across India. Further amendments may be needed to address jurisdictional conflicts and procedural delays.

Increasing Sanctioned Strength

The retirement age of the Presiding Officers has been increased from 62 to 65 years. And that of the Chairpersons of DRATs is increased from 65 to 70 years. More positions need to be created to handle the increasing caseload.

Related terms

- Debt Recovery Tribunal (DRT): The first-tier specialized tribunal for debt recovery from which appeals lie to DRAT

- Presiding Officer: The judicial officer heading a DRT

- Recovery Officer: Officer responsible for executing recovery orders passed by DRT

- Recovery Certificate: Document issued by DRT certifying the amount payable by the borrower

- Original Application (OA): Application filed by banks/financial institutions before DRT for debt recovery

- Securitisation Application (SA): Application filed under SARFAESI Act

- National Company Law Appellate Tribunal (NCLAT): Appellate tribunal for company law matters including insolvency

- Banking Ombudsman: Alternative dispute resolution mechanism for banking complaints

References

- ↑ DRAT as elaborated by Dept of Financial Services, available at https://financialservices.gov.in/beta/en/page/debts-recovery-tribunals-debts-recovery-appellate-tribunals (last visited on Nov 17, 2025)

- ↑ Raizada Associates Blog, available at https://www.raizadaassociates.com/blog/debt-recovery-appellate-tribunal-drat/ (last visited on Nov 17, 2025)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 The Recovery Of Debts And Bankruptcy Act, 1993, s. 8, available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?abv=CEN&statehandle=123456789/1362&actid=AC_CEN_2_33_00045_199351_1524048948493§ionId=5028§ionno=8&orderno=9&orgactid=AC_CEN_2_33_00045_199351_1524048948493

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Inserted by Enforcement of Security Interest and Recovery of Debts Laws and Miscellaneous Provisions (Amendment) Act, 2016, (w.e.f. 01.09.2016 vide N. No. S.O. 2831(E) dated 01.09.2016), amendment available at: https://www.drtcbe.tn.nic.in/Actsrules/SARFAESI%20AMENDMENT%20ACT%202016.pdf

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Inserted by Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016, section 249 and the Fifth Schedule, (w.e.f. 01.12.2019), amendment available at: https://ibclaw.in/the-fifth-schedule-to-insolvency-and-bankruptcy-code-2016/

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Inserted by RDDBFI (Amendment) Act, 2000 (w.e.f.17.01.2000), amendment available at: https://cdn.ibclaw.online/legalcontent/debtRecovery/RDB1993/Act/3.+RDDBFI+(Amendment)+Act+2000+25.03.2000+w.e.f.17.01.2000.pdf

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 The Recovery Of Debts And Bankruptcy Act, 1993, s. 20, available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?abv=CEN&statehandle=123456789/1362&actid=AC_CEN_2_33_00045_199351_1524048948493§ionId=5043§ionno=20&orderno=24&orgactid=AC_CEN_2_33_00045_199351_1524048948493

- ↑ The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016, s. 181, available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?abv=CEN&statehandle=123456789/1362&actid=AC_CEN_2_11_00055_201631_1517807328273§ionId=960§ionno=181&orderno=205&orgactid=undefined

- ↑ The Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest Act, 2002, s. 18, available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?abv=CEN&statehandle=123456789/1362&actid=AC_CEN_2_11_00037_200254_1517807324604§ionId=20661§ionno=18&orderno=22&orgactid=AC_CEN_2_11_00037_200254_1517807324604

- ↑ The Recovery Of Debts And Bankruptcy Act, 1993, s. 9, available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?abv=CEN&statehandle=123456789/1362&actid=AC_CEN_2_33_00045_199351_1524048948493§ionId=5029§ionno=9&orderno=10&orgactid=AC_CEN_2_33_00045_199351_1524048948493

- ↑ The Recovery Of Debts And Bankruptcy Act, 1993, s. 15A, available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?abv=CEN&statehandle=123456789/1362&actid=AC_CEN_2_33_00045_199351_1524048948493§ionId=5036§ionno=15A&orderno=17&orgactid=AC_CEN_2_33_00045_199351_1524048948493

- ↑ THE TRIBUNALS REFORMS ACT, 2021, available at:https://prsindia.org/files/bills_acts/acts_parliament/2021/The%20Tribunals%20Reforms%20Act,%202021.pdf

- ↑ The Tribunals Reforms Act, 2021, s. 3, available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?abv=CEN&statehandle=123456789/1362&actid=AC_CEN_2_2_00040_202133_1629961891898§ionId=57357§ionno=3&orderno=3&orgactid=AC_CEN_2_2_00040_202133_1629961891898

- ↑ The Recovery Of Debts And Bankruptcy Act, 1993, s. 11, available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?abv=CEN&statehandle=123456789/1362&actid=AC_CEN_2_33_00045_199351_1524048948493§ionId=5031§ionno=11&orderno=12&orgactid=AC_CEN_2_33_00045_199351_1524048948493

- ↑ The Tribunals Reforms Act, s. 6, available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?abv=CEN&statehandle=123456789/1362&actid=AC_CEN_2_2_00040_202133_1629961891898§ionId=57360§ionno=6&orderno=6&orgactid=AC_CEN_2_2_00040_202133_1629961891898

- ↑ The Recovery Of Debts And Bankruptcy Act, 1993, s. 10, available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?abv=CEN&statehandle=123456789/1362&actid=AC_CEN_2_33_00045_199351_1524048948493§ionId=5030§ionno=10&orderno=11&orgactid=AC_CEN_2_33_00045_199351_1524048948493

- ↑ The Recovery Of Debts And Bankruptcy Act, 1993, s. 11, available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?abv=CEN&statehandle=123456789/1362&actid=AC_CEN_2_33_00045_199351_1524048948493§ionId=5031§ionno=11&orderno=12&orgactid=AC_CEN_2_33_00045_199351_1524048948493

- ↑ The Tribunals Reforms Act, 2021, s. 5, available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?abv=CEN&statehandle=123456789/1362&actid=AC_CEN_2_2_00040_202133_1629961891898§ionId=57359§ionno=5&orderno=5&orgactid=AC_CEN_2_2_00040_202133_1629961891898

- ↑ The Recovery Of Debts And Bankruptcy Act, 1993, s. 13, available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?abv=CEN&statehandle=123456789/1362&actid=AC_CEN_2_33_00045_199351_1524048948493§ionId=5033§ionno=13&orderno=14&orgactid=AC_CEN_2_33_00045_199351_1524048948493

- ↑ The Tribunals Reforms Act, 2021, s. 7, available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?abv=CEN&statehandle=123456789/1362&actid=AC_CEN_2_2_00040_202133_1629961891898§ionId=57361§ionno=7&orderno=7&orgactid=AC_CEN_2_2_00040_202133_1629961891898

- ↑ The Recovery Of Debts And Bankruptcy Act, 1993, s. 14, available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?abv=CEN&statehandle=123456789/1362&actid=AC_CEN_2_33_00045_199351_1524048948493§ionId=5034§ionno=14&orderno=15&orgactid=AC_CEN_2_33_00045_199351_1524048948493

- ↑ The Recovery Of Debts And Bankruptcy Act, 1993, s. 15, available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?abv=CEN&statehandle=123456789/1362&actid=AC_CEN_2_33_00045_199351_1524048948493§ionId=5035§ionno=15&orderno=16&orgactid=AC_CEN_2_33_00045_199351_1524048948493

- ↑ The Tribunals Reforms Act, 2021, s. 4, available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?abv=CEN&statehandle=123456789/1362&actid=AC_CEN_2_2_00040_202133_1629961891898§ionId=57358§ionno=4&orderno=4&orgactid=AC_CEN_2_2_00040_202133_1629961891898

- ↑ The Recovery Of Debts And Bankruptcy Act, 1993, s. 17A, available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?abv=CEN&statehandle=123456789/1362&actid=AC_CEN_2_33_00045_199351_1524048948493§ionId=5039§ionno=17A&orderno=20&orgactid=AC_CEN_2_33_00045_199351_1524048948493

- ↑ The Recovery Of Debts And Bankruptcy Act, 1993, s. 18, available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?abv=CEN&statehandle=123456789/1362&actid=AC_CEN_2_33_00045_199351_1524048948493§ionId=5040§ionno=18&orderno=21&orgactid=AC_CEN_2_33_00045_199351_1524048948493

- ↑ The Debts Recovery Appellate Tribunal (Procedure) Rules available at: https://drat.tn.nic.in/ProcedureRules.htm

- ↑ The Recovery Of Debts And Bankruptcy Act, 1993, s. 21, available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?abv=CEN&statehandle=123456789/1362&actid=AC_CEN_2_33_00045_199351_1524048948493§ionId=5044§ionno=21&orderno=25&orgactid=AC_CEN_2_33_00045_199351_1524048948493

- ↑ Standard Chartered Bank v. Dharmender Bhohi - (2013) 15 SCC 341

- ↑ M/s Sidha Neelkanth Paper Industries Private Limited v. Prudent ARC Limited -2023 SCC Online SC 12

- ↑ US Courts and procedure, information taken from: https://www.uscourts.gov/about-federal-courts/court-role-and-structure/about-us-bankruptcy-courts? https://www.uscourts.gov/court-programs/bankruptcy? https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CPRT-118HPRT53949/pdf/CPRT-118HPRT53949.pdf? (last visited on Nov 25, 2025)

- ↑ UK Courts and procedure, information taken fromhttps://www.justice.gov.uk/courts/procedure-rules/civil/rules/insolvency_pd? https://www.judiciary.uk/courts-and-tribunals/business-and-property-courts/chancery-division/?(last visited on Nov 25, 2025)

- ↑ EU Courts and procedure, information taken from: https://academic.oup.com/oxford-law-pro/book/57816? https://www.liesegang-partner.com/knowhow/debt-collection/the-european-order-for-payment-procedure-and-the-european-enforcement-order-a-comprehensive-overview? https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2015/848/oj/eng?(last visited on Nov 25, 2025)

- ↑ Australia courts and procedure, information taken from: https://www.armstronglegal.com.au/commercial-law/national/corporations-law/australian-financial-security-authority-afsa/? https://www.fcfcoa.gov.au/gfl/bankruptcy/apply? https://www.fedcourt.gov.au/law-and-practice/guides/guides-bankruptcy/information-sheet-4? https://www.afsa.gov.au/owed-money/bankruptcy-notice? (last visited on Nov 25, 2025)

- ↑ Singapore courts and procedure, information taken from: https://www.duanemorris.com/articles/commencement_singapores_insolvency_restructuring_dissolution_act_2018_0820.html? https://io.mlaw.gov.sg/bankruptcy/who-is-the-official-assignee/? https://www.judiciary.gov.sg/civil/discharge-bankruptcy? https://io.mlaw.gov.sg/? https://sso.agc.gov.sg/Act/IRDA2018?(last visited on Nov 25, 2025)

- ↑ Japan courts and procedure, information taken from: https://amt-law.com/asset/res/publication_20250709001_ja_001.pdf? https://www.nishimura.com/en/knowledge/publications/20110408-39201 https://www.morihamada.com/system/files/publications/publications/pdf/GIRR_2010-11_MHM%EF%BC%88HP%EF%BC%89_1.pdf? https://www.japaneselawtranslation.go.jp/en/laws/view/125/en?(last visited on Nov 25, 2025)

- ↑ Canada courts and procedure, Information taken from:https://www.ic.gc.ca/app/scr/bsf-osb/ins/login.html? https://ised-isde.canada.ca/site/office-superintendent-bankruptcy/en? https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/b-3/?(last visited on Nov 25, 2025)

- ↑ DRT and DRAT Electronic Filing (Amendment) Rules, 2025, available at: https://ibclaw.in/debts-recovery-tribunals-and-debts-recovery-appellate-tribunals-electronic-filing-amendment-rules-2025/

- ↑ Digital case management - user manual and notice, available at: https://drt.gov.in/images/efiling_notice.pdf https://efiling.drt.gov.in/edrt/user_manual.pdf

- ↑ https://drt.gov.in/#/casedetail

- ↑ DFS - Data, available at: https://financialservices.gov.in/beta/en/page/debts-recovery-tribunals-debts-recovery-appellate-tribunals

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Daksh, "The State of Tribunals Report, pages 110-117" (Sept, 2025), available at: https://www.dakshindia.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/State-of-Tribunals-PDF-Digital.pdf?

- ↑ Naman Jain, "Debt Recovery Tribunals & Recovery of Debt Due to Banks and Financial Institutions" (August 30, 2021), Available at : https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3975290

- ↑ Mukesh Dwivedi and Aqa Raza, "Debt Recovery Tribunals in India: The Legal Framework" (August 12, 2016), Indian Journal of Law and Policy Review, ISSN 2456 3773, Volume 1, August, 2016, pp. 46-65, Available at:https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3066171&

- ↑ S. K. Katara & N. Shastri, "E-governance in Debts Recovery Tribunals and Debts Recovery Appellate Tribunals: A Framework for Implementation in India", available at: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/2691195.2691243?

- ↑ Debt Recovery Tribunal (DRT) UPSC Notes: Features and Powers, available at: https://testbook.com/ias-preparation/debt-recovery-tribunals-drt https://www.raizadaassociates.com/blog/debt-recovery-appellate-tribunal-drat/ (last visited on Nov 17, 2025)

- ↑ Enhancing Loan Recovery: The Impact of RDDBFI Act 1993 on Banking Operations, available at: https://thelaw.institute/business-law-as-applicable-to-co-operative-ii/loan-recovery-impact-rddbfi-act-1993-banking/ https://www.legalserviceindia.com/Legal-Articles/debt-recovery-tribunal/ https://testbook.com/ias-preparation/debt-recovery-tribunals-drt (last visited on Nov 17, 2025)

- ↑ https://www.barandbench.com/columns/debriefed-touching-5-crores-thats-what-the-pendency-of-cases-looks-like-in-india-statistics