Foreigner's Tribunal

The Foreigner’s Tribunal is a quasi-judicial body formed Chapter VI of The Immigration and Foreigners Order, 2025, formerly, Foreigner’s (Tribunals) Order, 1964. The Central Government issued this Order in exercise of the powers conferred under Section 7 of The Immigration and Foreigners Act 2025, formerly, Section 3 of the Foreigner’s Act, 1946 which accords the Central Government to refer questions to the Tribunal to decide with respect to all foreigners or concerning any particular foreigner or any prescribed class or description of a foreigner, to prohibit, regulate or restrict the entry and departure of foreigners into or from India or their presence or continued presence therein.

The Foreigners Tribunal has evolved as a mechanism to determine the citizenship status of individuals and is closely tied to India's legal frameworks for citizenship determination and security concerns[1]. The legal foundation for the handling of ‘foreigners’ in India was laid by the Foreigners Act, of 1946 which was enacted during British rule and empowered the government to regulate the entry, exit, and presence of non-citizens. It did not originally include provisions for tribunals to adjudicate on citizenship disputes. Due to concerns about cross-border migration, the government passed the Immigrants (Expulsion from Assam) Act, 1950 which allowed the expulsion of immigrants from Assam who were deemed detrimental to public interest. In response to increasing migration from Bangladesh (erstwhile East Pakistan), the government issues the Foreigners (Tribunals) Order, 1964 under the Foreigners Act to establish the tribunals. The tribunals were set up in Assam to tackle the concerns of illegal immigration.

The Assam Agitation led by the All Assam Student’s Union (AASU) demanding the identification and deportation of undocumented immigrants from Bangladesh culminated in the signing of the Assam Accords of 1985 between the government and Assamese leaders, which established a cut-off date for detection and deportation of foreigners – March 24, 1971. Section 6A was added to the Citizenship Act, of 1955 which created a special provision for Assam and reinforced the role and purpose of the Foreigners Tribunals in the implementation of the mandates of the Accord.The Illegal Migrants (Determination by Tribunals) Act of 1983 was introduced to determine the citizenship status of suspected foreigners in Assam. Unlike the present Foreigners Act, the burden of proof was placed on the state. This led to difficulties in the expulsion of suspected illegal immigrants by the government. In 2005, the Supreme Court held in the judgment of Sarbananda Sonowal vs. Union of India (2005)[2] that the IMDT Act was inefficient and was therefore repealed. The same led to the reinstating of the Foreigners Tribunals under the 1946 Act, which shifted the burden of proof back to the accused individuals.

The Immigration and Foreigners Act, 2025 came into force on September 1, 2025. The Foreigners Act, 1946, along with many other outdated pre-independence statutes and orders such as the Foreigners (Tribunal) Order, 1946 and the Immigrants (Expulsion from Assam) Act, 1950, were formally repealed and consolidated into a singular and modern framework. This comprehensive legislation standardizes and consolidates the regulation of foreign nationals' entry, stay, movement and exit across India, while introducing stricter registration, reporting and biometric data collection requirements to enhance monitoring and compliance by both individuals and employers.

The role of the Foreigners Tribunals has been strengthened significantly and statutorily redefined under Chapter VI of the Immigration and Foreigners Order, 2025. This replaces the earlier Foreigners (Tribunals) Order, 1946. Tribunals now operate with a jurisdiction beyond Assam and are empowered as first-class judicial magistrates to declare individuals as foreigners, adjudicate citizenship disputes and issue orders for deportation or detention. By standardizing procedures, timelines and appeals and even integrating digital verification through the Integrated Immigration Management System, the new order attempts to balance security imperatives with procedural safeguards, ensuring tribunals align with constitutional due processes while addressing persistent illegal migration concerns. This evolution signifies a transition from fragmented, state-specific mechanisms to a unified national framework for immigration governance.

Official Definitions

Foreigners Tribunal as defined in Legislation

The Immigration and Foreigners Act, 2025:

The Immigration and Foreigners Act, 2025 (formerly known as The Foreigners Act, 1946), is the act which empowers the Government to make provisions and orders with respect to foreigners in India. Section 2(f), erstwhile Section 2(a) of The Foreigners Act, 1946, of the act defines a foreigner as "a person who is not a citizen of India." Section 7 (formerly Section 3) of the act empowers the Central Government to make orders that may restrict, prohibit, allow or/and impose conditions on the entry, exit and movement of Foreigners in the territory of India. Through the powers of Section 3 of the Act, Foreigners (Tribunal) Order, 1964, which is now Chapter VI, Section 16, The Immigration and Foreigners Order, 2025, which created and empowered foreign tribunals with some of the powers under the Section.

The Immigration and Foreigners Order, 2025:

The Foreigners Tribunal (erstwhile The Foreigners (Tribunal) Order,1946) is passed under Chapter VI, Section 16 of The Immigration and Foreigners Order, 2025 which creates and empowers Foreign Tribunals. Section 16(1) of the Order, defines the Tribunals and their role, stating that "The Central Government or the State Government or the Union territory Administration or the District Collector or the District Magistrate may, by order, refer the question as to whether a person is or is not a foreigner within the meaning of the Act to a Foreigners Tribunal constituted for the purpose by the Central Government, for its opinion." Section 21 of the Order empowers the court with certain powers similar to that of a civil court while trying a suit, such as issuing commissions for the examining of witnesses, issuing summons and requiring the recovery and production of documents.

The Citizenship Act, 1955:

The Citizenship Act, 1955 supplements the Foreigners Act by defining the conditions and procedures for acquiring or losing Indian Citizenship. Through Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 1985, Section 6A was added to the Act which provides for special provisions as to the Citizenship of persons covered under the Assam Accords. It also outlines procedures for registration, electoral role deletion and enrollment etc. By Section 6A(e) of the act, a person shall be deemed to have been detected to be a foreigner on the date on which a Tribunal constituted under the Foreigners (Tribunals) Order, 1964, which is now Chapter VI, Section 16 of The Immigration and Foreigners Order, 2025, submits its opinion to the effect that he is a foreigner to the officer or authority concerned. As per Section 16(2) of Chapter VI of The Immigration and Foreigners Order, 2025, (previously, Section 2(1A) of the Foreigners (Tribunals) Order, 1964), The registering authority appointed under sub-rule (1) of rule 19 of the Citizenship Rules, 2009 may also refer to the Foreigners Tribunal the question whether a person of Indian origin, complies with any of the requirements under sub-section (3) of section 6A of the Citizenship Act, 1955 (57 of 1955).

Legal Provisions relating to Foreigners Tribunal.

Purpose & Jurisdiction

The primary purpose of the Foreigners Tribunal is to determine whether a foreigner staying illegally in India is a ‘foreigner’ or not[3]. The Tribunal operates in cases referred by the Border Security Force (BSF), local authorities, or through public complaints about the veracity of an individual’s citizenship. Although initially, only the Central Government could set these tribunals up to refer the question of whether a person is a foreigner or not within the meaning of its parent Act to a Tribunal constituted for this purpose, a 2019 Amendment expanded its ambit and empowered district magistrates in all states and UT’s for reference to Foreigners Tribunal’s if need be. As per Section 16(2) of The Immigration and Foreigners Order, 2025 [erstwhile Rule 1A of the The Foreigners (Tribunal) Order, 1946] The registering authority appointed under sub-rule (1) of rule 19 of the Citizenship Rules, 2009 [Substituted 'rule 16F of the Citizenship Rules, 1956' by Notification No. G.S.R. 409(E), dated 30.5.2019.] may also refer to the Tribunal the question whether a person of Indian Origin, complies with any of the requirements under sub-section (3) of Section 6A of the Citizenship Act, 1955 (57 of 1955).

In India, Foreigners Tribunals have been extended beyond Assam unlike before. Over 300 Tribunals are functioning in Assam, as of 2021 with an additional 200 being approved in principle to be added for the disposal of pending cases[4]. In India, under the provisions of both the The Immigration and Foreigners Act, 2025 and the The Immigration and Foreigners Order, 2025, only Foreigners Tribunals are empowered to declare the person as a foreigner. In Assam, the Tribunal addresses the issue of undocumented immigrants from neighboring nations, especially Bangladesh, and cases arising from the NRC process, where individuals excluded from the NRC list must prove their Indian citizenship[5].

The Ministry of Home Affairs has stated that the Foreigners (Tribunals) Amendment Order, 2019 applies to the entire country and that ‘it provides that one or more Foreigners Tribunals can be established in a state as per its requirement.[6]

Functioning of the Tribunal

Composition & Constitution of the Tribunal?

Each member is appointed under Chapter VI of The Immigration and Foreigners Order, 2025 as per the guidelines issued by the government from time to time. The Central Government or District Magistrate may by order, refer the question of the status of a person as to whether they are a foreigner or not, within the meaning of the The Immigration and Foreigners Act, 2025 to the Foreigners Tribunal. The Tribunal is to consist of a maximum of 3 members having judicial experience, such as judges, advocates, or civil servants as the Central Government may deem fit[7]. If there are two or more members, then one of the members is to be appointed as the Chairman of the Tribunal[8].

The following are the criteria laid down for the filling up of posts of members of the Foreigners Tribunal:

- Any willing serving or retired District/Additional District Judges (Grade I Officer). The retirement age of judicial officers will be 67 years old.

- Any practicing advocate who has completed 55 years of age with 10 years of practice. Any lawyers appointed will be on a contractual basis of 2 years or as extended accordingly and will be allowed to work till 60 years of age.

- Fair knowledge of the official language of Assam and its historical background[4]

Power of the Tribunal?

As per Section 21 of The Immigration and Foreigners Order, 2025, the Tribunal shall have the powers of a civil court while trying a suit under the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 and the powers of a Judicial Magistrate of the first class under the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023 in respect of the following matters, namely:—

- Summoning and enforcing the attendance of any person and examining him on oath;

- Requiring the discovery and production of any document;

- Issuing commissions for the examination of any witnesses

- Directing the proceedee to appear before it in person

- Issuing a warrant of arrest on non appearance of proceedee[9] if he fails to appear before it.

Procedure for Disposal of Questions

Referral of Questions

The Tribunal is empowered to regulate its procedure, subject to the wide mandates laid down within the order. Foreigners Tribunals may receive cases through these channels:

- Referral by Central and State Governments: The Central Government or the State Government or the Union territory Administration or the District Collector or the District Magistrate may, by order, refer the question as to whether a person is or is not a foreigner within the meaning of the Act to a Foreigners Tribunal constituted for the purpose by the Central Government, for its opinion within the meaning of the Immigration and Foreigners Act, 2025 [formerly, Foreigners Act, 1946].

- Referral by an officer not below the rank of Additional District Magistrate: The registering authority appointed under Rule 19 (1) of the Citizenship Rules, 2009, previously, Rule 16F(1) of the Citizenship Rules, 1956 may also refer to the Tribunal the question whether a person of Indian Origin, complies with any of the requirements under Section 6A(3) of the Citizenship Act, 1955.

- National Register of Citizens: In 2019, the NRC excluded more than 2 million people from its final list, the exclusion of which may be appealed to by the people at the Foreigners Tribunal for its opinion. As per Para 8 of the Schedule of the Citizenship (Registration of Citizens and Issue of National Identity Cards) Rules, 2003, which provides for the Special Provision as to the Manner of Preparation of National Registrar of Indian Citizens in the State of Assam, any person not satisfied with the outcome of the list may prefer an appeal before the Foreigner’s Tribunal within one hundred twenty days from the date of the order[10].

Referral by Central and State Governments

According to Section 16(1) of The Immigration and Foreigners Order, 2025, The Central Government or the State Government or the Union territory Administration or the District Collector or the District Magistrate may, by order, refer the question as to whether a person is or is not a foreigner within the meaning of the Act to a Foreigners Tribunal constituted for the purpose by the Central Government, for its opinion.

The Foreigners Tribunal shall serve on the person to whom the question relates, a copy of the main grounds on which he is alleged to be a foreigner and give him a reasonable opportunity of making a representation and producing evidence in support of his case and after considering such evidence as may be produced and after hearing such persons as may desired to be heard, the Foreigners Tribunal shall forward its opinion to the officer or authority specified in this behalf in the order of reference.[11]

The Foreigners Tribunal shall serve a show cause notice on the person to whom the question relates, that is, the proceedee. [12] The notice referred to in sub-paragraph (2) shall be served within 10 days of the receipt of the reference of such question by the Central Government or State Government or the Union territory Administration or any authority as specified in sub-paragraph (1) of paragraph 16.[13] The notice shall be served in English and also in the official language of the State indicating that the burden is on the proceedee to prove that he is not a foreigner.[14]

In case where notice is duly served, the proceedee shall appear before the Foreigners Tribunal in person or by a counsel engaged by him, as the case may be, on every hearing before the Foreigners Tribunal.[15] The Foreigners Tribunal shall give the proceedee 10 days time to give reply to the show cause notice and further ten days time to produce evidence in support of his case. [16] The evidence submitted to prove their citizenship can include documents like birth certificates, school certificates, land records, and other similar official documents.

Where the proceedee fails to produce any proof in support of his claim that he is not a foreigner and also not able to arrange for bail in respect of his claim, the proceedee shall be detained and kept in holding center.[17] The Foreigners Tribunal shall dispose of the case within a period of 60 days of the receipt of the reference from the Central Government or State Government or Union territory Administration or any authority as specified in sub-paragraph (1) of paragraph 16.[18] After the case has been heard, the Foreigners Tribunal shall forward its opinion as soon thereafter as may be practicable, to the officer or the authority specified in this behalf in the order of reference.[19] The final order of the Foreigners Tribunal shall contain its opinion on the question referred to, which shall be a concise statement of facts and the conclusion[20] A Foreigners Tribunal has to dispose of a case within 60 days of reference and on failure of proof of citizenship, the Tribunal has the power to send the person to a transit camp, for deportation thereafter.[21]

- Border Police: The Assam Police Border Organization, a wing of the State Police tasked with detecting foreigners, is empowered to refer a person it suspects to be a foreigner to a Tribunal. All police stations across Assam have the presence of the border police[22].

- Election Commission of India: In 1997, the Election Commission of India revised the electoral rolls in Assam which listed over 200,000 people as Doubtful or a D Voter. After the case of Sarbananda Sonowal vs. Union of India (2005)[23] in 2005, these cases were referred to the Foreigners Tribunal.

Referral by an officer not below the rank of Additional District Magistrate

According to Section 16(2) of The Immigration and Foreigners Order, 2025, The registering authority appointed under sub-rule (1) of rule 19 of the Citizenship Rules, 2009 may also refer to the Foreigners Tribunal the question whether a person of Indian origin, complies with any of the requirements under sub-section (3) of section 6A of the Citizenship Act, 1955 (57 of 1955).

The Foreigners Tribunal shall, before giving its opinion on the question referred to in sub-paragraph (2) of paragraph 16, give the person in respect of whom the opinion is sought a reasonable opportunity of making a representation and producing evidence in support of his case and after considering such evidence as may be produced and after hearing such persons as may desired to be heard, the Foreigners Tribunal shall forward its opinion to the officer or authority specified in this behalf in the order of reference.[24] The Foreigners Tribunal may take such evidence as may be produced by the registering authority appointed under sub-rule (1) of rule 19 of the Citizenship Rules, 2009, who has made the reference to the Foreigners Tribunal.[25] The Foreigners Tribunal shall dispose of the case within a period of sixty days of the receipt of the reference from the authority as specified in sub-paragraph (2) of paragraph 16.[26] After the case has been heard, the Foreigners Tribunal shall forward its opinion as soon thereafter as may be practicable, to the officer or the authority specified in this behalf in the order of reference.[27] The final order of the Foreigners Tribunal shall contain its opinion on the question referred to, which shall be a concise statement of facts and the conclusion.[28] Subject to the provision of this Order, the Foreigners Tribunal shall have the power to regulate its own procedure for disposal of the cases expeditiously in a time bound manner.[29]

- Procedure for setting aside of ex-parte orders If the Foreigners Tribunal has passed an ex-parte order for non-appearance of the proceeded and the individual possesses a sufficient cause for non-appearance, then on an application filed within 30 days or the said order, the ex-parte order may be set aside and the case may be decided accordingly. The proceedee may apply to the tribunal within 30 days to review the decision of the tribunal claiming that he is not a foreigner and such application may be reviewed within 30 days of receipt of the application[9].

Procedure for disposal of appeal

An appeal is to be filed within 120 days as specified under Para 8 of the Schedule appended to the Citizenship (Registration of Citizens and Issue of National Identity Cards) Rules, 2003 with a certified copy of the order of rejection received from the NRC authorities. The representation may be by way of appearance through a legal practitioner or a relation authorized by the appellant. The Tribunal shall issue notice for the production of NRC records within 30 days to the District Magistrate, who is to provide the same in original. In case no appeal is preferred, then the District Magistrate may refer to the Tribunal for its opinion on the question of whether the person is a foreigner or not. In case any FT has previously given an opinion about an individual earlier as a foreigner, then such person is ineligible to file an appeal to any Tribunal. If the Tribunal finds merit in the appeal, then a hearing shall be scheduled in the same regard. During the hearing, the Tribunal shall provide the appellant and government pleader with the opportunity to present their case and produce any evidence on their respective behalf, after which the Tribunal shall dispose of the appeal. If the appeal is rejected, then a clear reasoning is to be provided as to whether the appellant is a foreigner or not in the final order. The final order shall be given within a period of 120 days from the date of production of records[9].

Foreigners Tribunal as Defined in Official Government Reports.

Report on NHRC Mission to Assam’s Detention Centre's from 22 to 24 January, 2018

The NHRC published a report on its Mission to Assam’s Detention Centres in 2018 on the detention centers established for suspected illegal immigrants in Assam. It investigates the legality, due process, human rights concerns, and long-term implications of detaining suspected illegal immigrants. It criticizes the lack of a clear legal framework concerning a legal regime governing the detention centers (presently managed under the Assam Jail Manual). It criticizes the flaws in procedure and the denial of due process, by way of arbitrary declaration of foreigners ex-parte and the functioning of the Border Police who allegedly operate under a quota system with monthly targets to register a certain number of cases. The report also sets out certain recommendations for the Central Government, including the establishment of a legal framework for detention centers and ensuring due process along with requisite legal representation. The report also recommends expediting repatriation agreements as well as establishing a fast-track mechanism for those who admit to being foreigners. The report raises serious human rights concerns emphasizing that detention should not be indefinite and should not be punitive. It highlights systemic flaws in the tribunal's process, particularly the lack of legal aid and ex-parte judgments[30].

Foreigners Tribunal as defined in Case Laws

Md. Rahim Ali @Abdur Rahim vs. The State of Assam & Ors., 2024

In July 2024, the Supreme Court of India overturned a decision by a Foreigners Tribunal that had declared Md Rahim Ali a foreigner. The tribunal's ruling was primarily due to minor discrepancies in the spellings and dates within Ali's documents and the Court opined that in view of detailed analysis the discrepancies in the material produced by the appellant can be termed minor and not be deemed sufficient to lead the Tribunal to doubt and disbelieve the appellant and the version put forth by him. The Supreme Court's intervention underscored the need for tribunals to consider the socio-economic realities of individuals and not rely solely on minor inconsistencies when determining citizenship. The Court held that authorities cannot randomly accuse people of being foreigners and initiate investigation into a person’s nationality without there being some material basis or information to sustain the suspicion[31].

Mohammad Sanaullah’s Case, 2019

In Md. Sana Ullah vs The Union Of India, Mohammed Sanaullah, a retired Indian Army officer who had served for three decades, was declared a foreigner by a Foreigners Tribunal in May 2019. The tribunal's decision was based on a 2008 report by the Border Police, which alleged that Sanaullah was an "illiterate labourer" from Bangladesh. Following the tribunal's ruling, he was detained in a detention centre and was later released on bail by the Gauhati High Court[32]. This case garnered widespread attention and raised concerns about the procedures and evidentiary standards employed by the tribunals since a number of irregularities surfaced. In the inquiry report, the border police had written that Mr. Sanaullah was a labourer. The investigating officers claimed their signatures had been fabricated and that it may have been an administrative mix-up but it was on the basis of these material that the Tribunal had concluded on the status of Mr. Sanaullah as a foreigner[33].

Rahima Khatun vs. Union of India, 2017.

In Rahima Khatun, The Gauhati High Court set aside an ex-parte order passed by the Foreigners Tribunal which declared the petitioner to be an illegal migrant, on the basis that the same had been passed without providing the petitioner the opportunity to be heard and remanded the same back to the Tribunal for reconsideration. The Court set aside the same by opining that, “citizenship is one of the most important rights of a person. By virtue of citizenship, one becomes a member of a sovereign country and becomes entitled to various rights and privileges granted by law in the country and, as such, if any question arises about citizenship of a person, in our opinion, the same should be adjudicated as far as possible on the basis of merit and on hearing the person concerned”. This judgement is in alignment with a number of judgements which set aside ex-parte orders by the Foreigners Tribunal in cases including Asor Uddin vs. Union of India[34], Md. Misher Ali @ Meser Ali v. Union of India[35] and Mamtaz Begum vs Union of India[36] by both the Supreme Court as well as the Gauhati High Court[37].

Golapi Begum vs. Union of India, 2020

In Golapi Begum v. Union of india, the Gauhati High Court held that the Tribunal overstepped its jurisdiction in declaring the petitioner as a foreigner on the basis of a ground that it was not referred to it and opined that the Tribunal cannot assume suo-motu jurisdiction to render an opinion beyond what is sought. The matter was sent back to the Tribunal for reconsideration. The High Court held that essentially the Tribunal went beyond the reference as no opinion was sought as to the date of entry of the petitioner into India and stated that the Tribunal was only required to answer the reference and not beyond the terms it dictates[38].

Sarbananda Sonowal vs. Union of India & Anr, 2005.

In Sarbananda Sonowal vs. Union of India, the Supreme Court struck down the Illegal Migrants (Determination by Tribunals) Act, 1983 as unconstitutional. The Act was identified as a major hurdle to identification of illegal migrants since, inter alia, it put the burden of proof on the prosecution. Article 355 of the Indian Constitution, which requires the Centre to protect every State from external aggression, and Article 14 i: e Right to Equality was relied on. It was also declared that illegal immigration counts as external aggression. Article 14 was applied on the ground that the IMDT Act has been made applicable only to the State of Assam, and had no rational nexus. The IMDT Act, placed the burden on the state to prove that someone is not a citizen. With this judgement, the same was reversed, with the burden now falling on the accused to prove citizenship[39].

Rejia Khatun vs. Union of India & Ors, 2025.

Rejia Khatun, a resident of Tezpur, was facing two proceedings before two different benches of the Foreigner’s Tribunal at the behest of the state. While the first was initiated in 2012, the second was launched in 2016. In 2018, the bench hearing the proceedings initiated in 2016 declared her an Indian citizen. All documentary as well as oral evidence was taken into account before the declaration was made. However, in 2019, the co-ordinate bench before which the 2012 proceeding was pending refused to drop it, despite Khatun’s plea to do so. It said the February 2018 order did not divest it of the power to adjudicate the issue afresh. This order was upheld by the Guwahati HC[40].

The Supreme Court overruled the High Court's Order on the grounds that a foreigners tribunal, established for determining illegal immigrants, is “powerless” to review its own orders since the law does not permit it to act as an appellate authority over its own judgments. Once an individual has been declared an Indian citizen through due process, the state or the Centre cannot pursue repetitive litigation against them in the absence of fresh and valid grounds for review through an appropriate appellate mechanism.[41]

Official Database

Parliamentary Response

RAJYA SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. 2306

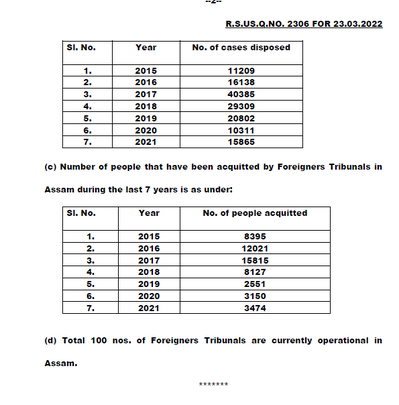

This database is based on an official parliamentary response submitted in the Rajya Sabha on the 23rd of March 2022 by the Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. It documents the aggregate and year-wise statistics on cases which are referred to, disposed of as well as those that are pending before Foreigners’ Tribunals and it even gives the number of people that were acquitted by these quasi-judicial bodies in a period of 7 years from the year 2015 to the year 2021. As of 31st of December, 2021, the data shows a total of 4,35,282 cases which had been referred to the Foreigners’ Tribunals in Assam out of which 3,09,048 cases had been disposed of which left 1,23,829 cases ongoing or pending. It further includes the yearly or annual data of the years 2015–2021 on the number of cases disposed of each year and the number of people acquitted during the same time period. Additionally, the dataset also provides the institutional capacity of the system by taking note that One Hundred (100) Foreigners’ Tribunals were operating in the state of Assam at the time of reporting.

RAJYA SABHA STARRED QUESTION NO. *45

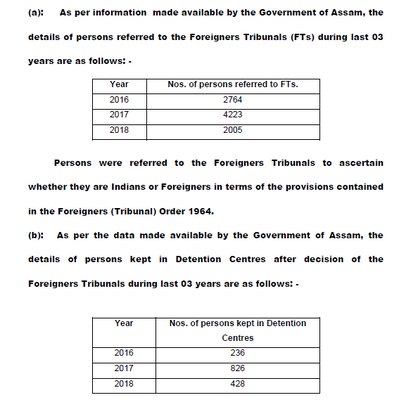

This dataset is an official parliamentary response submitted in the Rajya Sabha on the 6th of February, 2019, by the Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. This data is sourced from the information given by the Government of Assam and records referrals to the Foreigners' Tribunals, the details of persons kept in Detention Centres after decision of the Foreigners Tribunals and the details of people released from Detention Centre all in a 3 year period. The database ranges from the years 2016-2018 including the number of persons were referred to the Foreigners Tribunals to ascertain whether they are Indians or Foreigners in terms of the provisions contained in the Foreigners (Tribunal) Order 1964. Persons were released from the Detention Centres on the basis of opinion given by the Foreigners Tribunals or Higher Courts or for repatriation to their native Country.

RAJYA SABHA STARRED QUESTION NO. *259

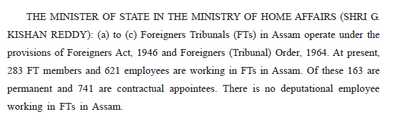

This database is an official parliamentary response submitted in the Rajya Sabha on 18 March 2020 by the Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. The information given in this response is sourced from the Government of Assam which outlines the legal framework and institutional staffing of Foreigners’ Tribunals operating in the state at the time.

The data specifies that Foreigners Tribunals (FTs) in Assam operate under the provisions of Foreigners Act, 1946 and Foreigners (Tribunal) Order, 1964. At present, 283 FT members and 621 employees are working in FTs in Assam. Of these 163 are permanent and 741 are contractual appointees. There is no deputational employee.

Research engaging with the Foreigners Tribunal

Sarfaraz Nawaz & Surajit Das, “A Panacea Bad in Law (A Study into the Origin, Nature and Constitutional Validity of Foreigners Tribunals)" (2021).

Written by Sarfaraz Nawaz and Surajit Das, “A Panacea Bad in Law (A Study into the Origin, Nature and Constitutional Validity of Foreigners Tribunals)" ,the Article, while acknowledging illegal immigration as a critical issue in India, believes that legality should be prioritized and no Indian citizen should be deprived of his citizenship by an illegal mechanism. Questioning the constitutional validity of the tribunal itself, the article raises 2 major questions. The first being, whether Foreigners Tribunals can be constituted by executive fiat instead of legislation? And the second, questioning whether Section 3 actually empowered the Central Government to pass an order for constitution of Foreigners Tribunals for deciding the fate of thousands of doubtful citizens or suspected foreigners. For Foreigners Tribunals, it has been contended from time to time that their constitutionality is suspect as they adjudicate an issue which is beyond the ambit of Article 323-B of the Indian Constitution, which empowers the state to set Tribunals for various matters such as tax, industrial and labour disputes etc. It further questions the validity and constitutional limitations of Section 3, which is a delegated legislation. In conclusion, the Article calls the foreign tribunals set up in India Unconstitutional, and recommends amendments to be made to the current system[42].

"Designed to Exclude: How India's Courts Are Allowing Foreigners Tribunals to Render People Stateless in Assam", Amnesty International (2019)

Amnesty International published a report titled “Designed to Exclude: How India's Courts Are Allowing Foreigners Tribunals to Render People Stateless in Assam" which conducts an in-depth analysis of the systemic issues associated with the Foreigners Tribunals (FTs) in Assam, highlighting their procedural flaws, human rights violations, and the complicity of the Indian judiciary in perpetuating the exclusionary practice.[43] The report argues that India's judiciary, including the Supreme Court and Gauhati High Court, has legitimized the exclusion of people, especially those of Bengali origin, by endorsing national security narratives over human rights concerns. Courts have upheld discriminatory legal provisions and denied individuals fair trial standards. Key rulings, such as Sarbananda Sonowal v. Union of India (2005)[44], equated migration with "external aggression," leading to the dilution of constitutional protections. The report highlights how the Foreigners Tribunal contravenes international legal obligations under treaties such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Convention on the Rights of the Child. Arbitrary deprivation of nationality has resulted in prolonged detention, forced separation of families, and socio-economic hardships.

“Identifying the ‘Outsider’: An Assessment of Foreigner Tribunals in Assam”, Talha Abdul Rahman (2020)

Talha Abdul Rahman in the article, “Identifying the ‘Outsider’: An Assessment of Foreigner Tribunals in Assam” critically examines the functioning of Foreigners Tribunals (FT) in Assam, particularly in the context of the NRC. It argues that Assam has a long history of migration and identity-based conflicts, often politicized to serve nationalist interests. The NRC process which excluded 1.9 million residents in 2019, has placed an immense legal and social burden on those deemed ‘foreigners’, particularly affecting Bengali-speaking Muslims. It raises concerns about the lack of independence and transparency in FTs, including criticizing the lack of clear judicial criteria and allowing lawyers with minimal experience to serve as adjudicators, which in turn raises questions about due process, bias, and fairness, given the tribunal's power to render individuals stateless. The article ultimately argues that the FTs are designed to exclude rather than fairly adjudicate regarding claims of citizenship and underscores the need for legal reforms including independent judicial oversight and an assessment of the tribunals functioning in line with constitutional and international human rights[45].

“Beyond Papers: Understanding the Making of Citizenship in the Foreigners Tribunals of Assam”, Fariya Yesmin (2024)

In the article titled, “Beyond Papers: Understanding the Making of Citizenship in the Foreigners Tribunals of Assam” by Fariya Yesmin, the belief that citizenship in Assam’s FTs is determined through documentary evidence is challenged and it argues that there is an interplay between legal, social and bureaucratic processes that construct the notion of ‘citizenship’, which is further shaped by factors such as class, religion, language, etc. The paper undertakes ethnographic research with lawyers, border police, tribunal members and individuals affected which brings out that the possession of documents does not necessarily become a guarantee of recognition as a citizen. It highlights structural flaws within the tribunal system by pointing out the procedural inconsistencies and influences that shape the outcomes of the tribunal’s decisions. It points out that the reversal of the burden of proof places undue hardships on individuals, who may lack the legal literacy or financial means to navigate through the process effectively. It critiques the religious and class-based profiling that disproportionately targets Bengali-speaking Muslims as being foreigners. It stresses that the production of citizenship therefore becomes performative, requiring individuals to align their narratives with the expectations doled out by tribunal members, with those who fail to meet the same being rendered stateless[46].

"Access to Justice for Women under Foreigner’s Tribunal Act, 1946 in Assam" Nargis Choudhury (2023)

In the paper titled "Access to Justice for Women under Foreigner’s Tribunal Act, 1946 in Assam", Nargis Choudhury highlights how women are disproportionally affected by the orders passed by the Foreigners Tribunals. Many of them are illiterate, or have had to move from one village to another when they were married off before the age of 18. This complicates the documentation process, since their primary form of documentation i: e the voter list, bears the husband's name. This is further exacerbated because of the NRC (National Register of Citizens), 2019, which excluded around 1.9 Million People, rendering them at the risk of statelessness. The paper also highlights the egregious conditions in the Detention Camps, which are over-crowded, lack basic amenities and have strict rules on visits from family. Pregnant women are the worst affected by this. To be released from such camps, women detainees face additional challenges such as furnishing securities and securing assurances from citizens. It also highlights judgements such as Aktara Begum V. UOI (2017)[47], in which the Gauhati High Court granted the Foreigners Tribunal the authority to initiate investigations into the citizenship status of an individual's extended family members after declaring them as foreigners. This decision raises significant concerns about mass statelessness and violates India's international obligations under the Convention on the Rights of the Child and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights In conclusion, the paper shows how women face major hurdles in accessing Justice such as Discriminatory Laws and Practices, Gender Discrimination, Patriarchy, Deprivation of Legal Information and Economic Vulnerabilities[48].

"Unmaking Citizens: The Architecture Of Rights Violations And Exclusion In India’s Citizenship Trials." Mohsin Alam Bhat, Arushi Gupta and Shardul Gopujkar.

The paper titled "Unmaking Citizens: The Architecture Of Rights Violations And Exclusion In India’s Citizenship Trials." highlights how Foreigners Tribunals, rather than being flawed exceptions, have become routine instruments of exclusion, supported by legal reasoning that often disregards due process and constitutional safeguards. The report calls for a fundamental rethinking of the legal structures governing citizenship in India, calling the current regime not just broken, but actively unjust. A full bench judgment of the Gauhati High Court, Moslem Mondel (2013)[49] and Supreme Court judgements such as Rahim Ali (2024)[50] , had affirmed that the burden of proof cannot shift to the accused unless the state first provides meaningful information and a fair opportunity to respond. However, these principles are rarely followed by the Foreigners Tribunals[51]. Moreover, the Gauhati High Court has failed at upholding the same in several cases, by consistently treating procedural failures in the referral process as remediable technicalities rather than as fundamental violations, thereby lowering the threshold for lawful referral. It highlights the issues within the system, such as denial of access to inquiry reports and the shielding of inquiry officers. This is further exacerbated by the lengthy proceedings of the courts and the non-compliance of laid down procedures, leading to the denial of citizenship for several genuine cases[52].

"Death by Paperwork: Determination of Citizenship and Detention of Alleged Foreigners in Assam" Kalantry, Sital and Tarafder, Agnidipto.

The paper titled "Death by Paperwork: Determination of Citizenship and Detention of Alleged Foreigners in Assam" [53] illustrates how state-led administrative processes, under the guise of documentation and adjudication, produces de facto stateless populations without any formal denationalization law. By reversing the burden of proof and operating through opaque tribunals, the state's processes strip individuals, many of whom have lived in Assam for generations of their citizenship. The resultant Statelessness is real, impactful, and deeply stigmatizing. The paper also delves into provisions of international conventions like the ICCPR and how several actions constitute a violation of the same. The tribunals are criticized for not being impartial, for holding the trials in private, for having the power to pass ex-parte judgements against alleged foreigners without allowing the presence of the latter during their proceedings and for the lack of access to translators. The worst affected by the tribunal's orders are women, children and transgender persons who often lack the access to justice. The conditions of women’s detention as compared to men’s constitute discrimination. The NRC and FT processes punish children whose families deviate from the traditional patriarchal family structure. Orphans and children born to unmarried women, in particular, struggle to establish their lineage in the absence of a present father. Due to societal ostracization, many of India’s transgender persons were abandoned by, or estranged from, their families at a young age and live in isolated “hijra” communities with other transgender persons. As a result, transgender persons lack access to birth certifcates and other accepted documents, such as land entitlements and immunization and school matriculation records, which prevented their successful application to the NRC.[54]

" 'The Right to Have Rights: Assam and the Legal Politics of Citizenship' ", Padmini Baruah (2020)

Padmini Baruah's article titled "The Right to Have Rights: Assam and the Legal Politics of Citizenship" examines how citizenship in Assam has been brought down to an uncertain legal status through documentary regimes and quasi-judicial processes. The author begins the paper by describing citizenship as a bureaucratic exercise at its core, and similar to all bureaucratic practices, it mandates a paper trail. Documentation is supposed to be both proof and power since citizenship documents are "to be perceived as an instrument of power exercised at the behest of the state" [55]

Baruah says that historically, Assam has witnessed a decades-long movement against the presence of 'illegal' immigrants tracing Assam's long-standing worries around colonial settlement policies, migration, partition and the Assam agitation. These various developments produced a political narrative centered around identifying and expelling the "illegal immigrant". In this context, the author argues that "a documentary regime has become the primary tool of exclusion, reinforcing existing societal notions around the idea of immigrants."[56] The updating of the National Register of Citizens (NRC), which resulted in the exclusion of around 1.9 million people, exemplifies how documentation requirements disproportionately affect the poor, minorities and women.

The article mainly probes the functioning of Foreigners Tribunals (FTs), with Baruah's evidence based analysis of around 90 cases revealing procedures that are deeply flawed. Particularly, "in the absence of transparency on what amounts to appropriate proof of identity, tribunals have exercised free discretionary reign over the evidentiary process."[57] Valid and legal documents are often rejected on arbitrary grounds, notices are defectively served and jurisdictional limits are routinely exceeded.

Most of the time even women are unfairly and disproportionately harmed by documentational norms as they are patriarchal and are in the favor of patrilineal lineage which many women are structurally unable to establish. Ultimately, the author finishes the paper with the conclusion that these processes produce conditions of de-facto statelessness, where these individuals have their legal identity and protection taken away from them. As Baruah emphasizes, citizenship is the "'right to have rights'" and those kept away from it are consequently denied access to a complete array of social, political and legal rights.

"Strangers in Their Own Land: Assam's Bengali-Origin Muslims Face Disenfranchisement and Indignity", Makepeace Sitlhou (2022)

Makepeace Sitlhou's Strangers in their Own Land shows how Muslims with Bengali-origins in Assam are depicted socially, legally and psychologically alien through India's citizenship-verification regime. This article starts with the story of Abubakkar Siddique. His experience is an example of how citizenship scrutiny brings long lasting indignity instead of closure. Even after his release from detention, Siddique is under surveillance constantly. The author even notes that Siddique's voter card and police logbook have become his "lifeline". Siddique's lawyer later observes, "He may be out of jail but he's still a prisoner." [58]

Pointing out these individual experiences and examples withing a wider political framework, Sitlhou explains that Bengali-origin Muslims "have come to be perceived increasingly as foreigners in their own state. "Even though so many families have lived in Assam for years and generations, institutions like the Foreigners Tribunals (FTs), The National Register of Citizens (NRC) and the Border Police have changed the belonging into a matter of documentation and suspicion. The NRC process which reviewed millions of documents, left 1.9 million people left vulnerable to detention and excluded, despite the fact that the registry "does not determine citizenship."[59]

This article shows how arbitrariness defines these processes. Sitlhou mentions that "those under trial must build cases for themselves without ever learning on what grounds they were suspected,"[60] since inquiry reports are often kept silent or just incomplete. Border Police's investigations have routinely lacked evidence, still cases go ahead regardless. Even when documents such as the voter lists and records or even the NRC entries are produced, they are often dismissed on prejudicial or technical grounds.

Sitlhou goes on to expose the role of vigilante groups and the political pressure in amplifying this system. Together, both non-state and state actors have formed what Sitlhou describes as "a legal purgatory of statelessness in perpetuity."[61] The article finishes off concluding that citizenship enforcement in Assam is less about legality and more about control, leaving thousands suspended between detention, freedom. belonging and exclusion.

References:

- ↑ Sarfraz Nawaz and Surajit Das, "A Panacea Bad in Law (A Study into the Origin, Nature and Constitutional Validity of Foreigners Tribunals)" https://www.scconline.com/blog/post/2021/11/02/a-panacea-bad-in-law/

- ↑ Sarbananda Sonowal v. Union of India, (2005) 5 SCC 665 (S.C. Ind.).

- ↑ Section 16(1), The Immigration and Foreigners Order, 2025

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. 3280 https://www.mha.gov.in/MHA1/Par2017/pdfs/par2021-pdfs/LS-16032021/3280.pdf

- ↑ India’s National Register of Citizens Threatens Mass Statelessness, Princeton Sch. of Pub. & Int’l Affs. (May 12, 2021), https://jpia.princeton.edu/news/indias-national-register-citizens-threatens-mass-statelessness

- ↑ Rajya Sabha Debates. https://rsdebate.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/699453/1/IQ_249_03072019_U1329_p173_p173.pdf

- ↑ Section 16(4), The Immigration and Foreigners Order, 2025

- ↑ Section 16(5), The Immigration and Foreigners Order, 2025

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Section 19, The Immigration and Foreigners Order, 2025

- ↑ Para 8, Schedule of the Citizenship (Registration of Citizens and Issue of National Identity Cards) Rules, 2003

- ↑ Section 17(1), The Immigration and Foreigners Order, 2025

- ↑ Section 17(2), The Immigration and Foreigners Order, 2025

- ↑ Section 17(3), The Immigration and Foreigners Order, 2025

- ↑ Section 17(4), The Immigration and Foreigners Order, 2025

- ↑ Section 17(7), The Immigration and Foreigners Order, 2025

- ↑ Section 17(8), The Immigration and Foreigners Order, 2025

- ↑ Section 17(13), The Immigration and Foreigners Order, 2025

- ↑ Section 17(14), The Immigration and Foreigners Order, 2025

- ↑ Section 17(15), The Immigration and Foreigners Order, 2025

- ↑ Section 17(16), The Immigration and Foreigners Order, 2025

- ↑ Centre for Justice & Peace, "Foreigners’ Tribunals: Why were they established and how do they operate?" https://cjp.org.in/all-you-ever-wanted-to-know-about-foreigners-tribunals/

- ↑ Sagar, "Case Closed: How Assam’s Foreigners Tribunals, aided by the high court, function like kangaroo courts and persecute its minorities", The Caravan https://caravanmagazine.in/law/assam-foreigners-tribunals-function-like-kangaroo-courts-persecute-minorities

- ↑ Sarbananda Sonowal v. Union of India, (2005) 5 SCC 665 (S.C. Ind.).

- ↑ Section 18(1), The Immigration and Foreigners Order, 2025

- ↑ Section 18(2), The Immigration and Foreigners Order, 2025

- ↑ Section 18(4), The Immigration and Foreigners Order, 2025

- ↑ Section 18(5), The Immigration and Foreigners Order, 2025

- ↑ Section 18(6), The Immigration and Foreigners Order, 2025

- ↑ Section 18(7), The Immigration and Foreigners Order, 2025

- ↑ National Human Rights Commission, Report on NHRC Mission to Assam’s Detention Centres (Jan. 22–24, 2018), in Report on NHRC Mission to Assam's Detention Centres, at 1 (Mar. 26, 2018), https://cjp.org.in/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/NHRC-Report-Assam-Detention-Centres-26-3-2018-1.pdf

- ↑ Md. Rahim Ali @ Abdur Rahim vs The State Of Assam 2024 INSC 511

- ↑ onaullah @ Md. Sanaullah v. Union of India & Ors., I.A. (Civil) 1877/2019 in W.P. (C)

- ↑ Manu Sebastian, "Ex-Army Man, Who Was Detained After Being Declared A 'Foreigner' By Assam Tribunal, Moves Guahati HC For Release". https://www.livelaw.in/top-stories/ex-army-man-who-was-detained-after-being-declared-a-foreigner-moves-guahati-hc-for-release-145395?fromIpLogin=78340.67736311567

- ↑ WP(C)/6544/2019

- ↑ Review.Pet. 5/2020

- ↑ WP(C)/1851/2017

- ↑ WP(C) No.8284/2019

- ↑ WP(C) No.2434/2020.

- ↑ (2005) 5 SCC 665

- ↑ WP(C)/2811/2020

- ↑ Crl.A. No. 000672 / 2025

- ↑ Sarfraz Nawaz & Surajit Das, A Panacea Bad in Law: A Study into the Origin, Nature and Constitutional Validity of Foreigners Tribunals, SCC Online Blog (Nov. 2, 2021), https://www.scconline.com/blog/post/2021/11/02/a-panacea-bad-in-law/

- ↑ Amnesty International, Designed to Exclude: How India’s Citizenship Laws Violate Human Rights (July 2018), https://www.amnesty.be/IMG/pdf/rapport_inde.pdf

- ↑ 2005 (5) SCC 665

- ↑ Abdul Rahman, Talha, Identifying the ‘Outsider’: An Assessment of Foreigner Tribunals in the Indian State of Assam (June 29, 2020). Vol 2 No 1 (2020): Statelessness & Citizenship Review , Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3723694

- ↑ Yesmin, F. (2024). Beyond papers: understanding the making of citizenship in the Foreigners’ Tribunals of Assam. Contemporary South Asia, 32(4), 475–488. https://doi.org/10.1080/09584935.2024.2413957

- ↑ Writ Petition (Civil) 260 of 2017, Gauhati High Court

- ↑ Access to Justice for Women under Foreigner’s Tribunal Act, 1946 in Assam, Nargis Choudhury, Mahanirban Calcutta Research Group, Public Policy Paper No. 148 (May 2018), http://www.mcrg.ac.in/PP148.pdf

- ↑ State of Assam & Ors. v. Moslem Mondal & Ors., 2013 (1) GLT 809.

- ↑ Md. Rahim Ali @ Abdur Rahim vs The State Of Assam (2024). 2024 INSC 511

- ↑ Article‑14, Unmaking Citizens: The Architecture of Rights Violations & Exclusion in India’s Citizenship Trials, (July 26, 2025), https://article-14.com/post/unmaking-citizens-the-architecture-of-rights-violations-exclusion-in-india-s-citizenship-trials-6884b2d47b1b9

- ↑ National Law School of India University, Unmaking Citizens: The Architecture of Rights Violations — Online Report, (July 2025), https://www.nls.ac.in/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Unmaking-Citizens_online-report.pdf.

- ↑ Sital Kalantry & Agnidipto Tarafder, Death by Paperwork: Determination of Citizenship and Detention of Alleged Foreigners in Assam, Cornell Legal Studies Research Paper (June 25, 2021), available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3873978 (last visited July 17, 2025)

- ↑ https://download.ssrn.com/21/06/26/ssrn_id3873978_code1215500.pdf?response-content-disposition=inline&X-Amz-Security-Token=IQoJb3JpZ2luX2VjELT%2F%2F%2F%2F%2F%2F%2F%2F%2F%2FwEaCXVzLWVhc3QtMSJGMEQCIGqXMBvdR8x31dpoFPoJ1V3fX4AqztWISVavO6s22J6hAiBUnNim2X%2FawZ9P2ElsgW%2BsnELKgTwRH%2BlkvCrWTIGhyiq9BQgcEAQaDDMwODQ3NTMwMTI1NyIMDK9p%2Fv5hH7pyCnoNKpoFpzwePENDPdNSQzCp5GRnjWsAc0wQHDGmrwsHIt5dBEDW9pBPklnZ6Ha5Qy1rG%2FlK9kA3qV3woGHoOiWqeWPgLqF9mZ1cORLtDKX5i8Q9dKK0Eb3B5JaGnXQVHoK9uMC5mQ0UCGP4vuw1ZMs20MkM%2BN920tvf%2Bhzu2B8MVRoED4SnKQYdsjtF9WW3sS15rnUC0qmPGlKDid7IjvW9G0DYQ7FmP2%2Bej40ajpsREHiNiQNPvju57lVlT%2BV6gQ4H5jjhu9jYKWvXL42ip3k8VRsCuV%2FgNmbsI4HA%2FebYZoN04%2FrOR%2BySTez5Kd%2BzILia%2F6%2BeP5%2BoOdh3TRL0lhvmTAJeS1ZN3ck8SCIVA99ljKVurNgdgJiuMUromu9Y6mNIX2DkITyge9O7UpcLuOA%2BW4rzBUntiZqdts0lBKEu0mLJrayQil372M2ncgou260utkIeJZcH0mrnxtWqEFeajuSZo6oYqqUpdzZbeqVnINJJhwQxv2FqX49MZs1WJKLbX1QlcbAO89xg%2F6tkKmMe8ewjWVFAe2tYpwOrOtWQOrhgrPMLrAhbecLDy%2BjSvVFJCfF%2Fjf6Nzitp3cUg%2Bi6Q%2BHoxkxVjdwel0ZKaKpT7anXIytZcFYP%2BSnaAx9q%2FVyylHFJBH%2Bl0jmVv1qHa43iwgRCI%2B%2Bpqq%2B6rdpLJZxb903aCKT2Bj9HFa04Nn%2BsVVvIYvekPwyk5E0FeOUGysF9BaRKgSNvbeRUOqiMbL181OCLFid204ibQRzq0idYnV479Z9yA5SUFsHZPOReBd%2BeKsZmVO3nk2bv7o8hkdVgZk4Cl54kcDX5lV2tIQWar191BT4MVx3gl8sNDfgsO0ITqt7%2Fc%2B3APSS6bAqZhJXlINg5qDNtD7UyHmsQLQBrOMPPg18UGOrIBP8Dt8TThVGUbEl2bbqlVSVAhfmMxYJIGHmC%2BSXob9E8iYu7YLjkPG2MNeqsYM%2BPmBqqyc80iV0n1lycXFGfO%2FBXoxXhVBAhhGXMOvsCzZvjfu3C9a%2BMTQDJZ0iCr6a3y74Q3j5ncs8%2BCAUFn8XGsxWu1UrolyoKFGuofCgjsBvyA5kCLGr4JOChxyobS%2Fh96ETapdI7IHYwetuk7erwRRA7ZInQ5kSGHab%2BcSB%2F3TAUpQg%3D%3D&X-Amz-Algorithm=AWS4-HMAC-SHA256&X-Amz-Date=20250901T194343Z&X-Amz-SignedHeaders=host&X-Amz-Expires=300&X-Amz-Credential=ASIAUPUUPRWE4FQH6FV7%2F20250901%2Fus-east-1%2Fs3%2Faws4_request&X-Amz-Signature=4f1c6be2fd0c10001a78ef868dfe7d5822ab1d956b4910e1e3799a8bfc3f9450&abstractId=3873978

- ↑ Padmini Baruah, “The Right to Have Rights”: Assam and the Legal Politics of Citizenship, 16 Socio-Legal Rev. 17 (2020), https://heinonline.org/HOL/Page?handle=hein.journals/soclerev16&id=183&collection=journals&index=

- ↑ Padmini Baruah, “The Right to Have Rights”: Assam and the Legal Politics of Citizenship, 16 Socio-Legal Rev. 17 (2020), https://heinonline.org/HOL/Page?handle=hein.journals/soclerev16&id=183&collection=journals&index=

- ↑ Padmini Baruah, “The Right to Have Rights”: Assam and the Legal Politics of Citizenship, 16 Socio-Legal Rev. 17 (2020), https://heinonline.org/HOL/Page?handle=hein.journals/soclerev16&id=183&collection=journals&index=

- ↑ Makepeace Sitlhou, Strangers in Their Own Land: Assam’s Bengali-Origin Muslims Face Disenfranchisement and Indignity, No. 65 The Baffler 26 (2022), https://www.jstor.org/stable/27169056

- ↑ Makepeace Sitlhou, Strangers in Their Own Land: Assam’s Bengali-Origin Muslims Face Disenfranchisement and Indignity, No. 65 The Baffler 26 (2022), https://www.jstor.org/stable/27169056

- ↑ Makepeace Sitlhou, Strangers in Their Own Land: Assam’s Bengali-Origin Muslims Face Disenfranchisement and Indignity, No. 65 The Baffler 26 (2022), https://www.jstor.org/stable/27169056

- ↑ Makepeace Sitlhou, Strangers in Their Own Land: Assam’s Bengali-Origin Muslims Face Disenfranchisement and Indignity, No. 65 The Baffler 26 (2022), https://www.jstor.org/stable/27169056