Wrongful prosecution

This page is now open for community updates

What is ‘Wrongful Prosecution’

Wrongful Prosecution also called as Malicious Prosecution refers to the act of initiating a civil or criminal lawsuit against another person without any grounds or probable cause..[1] Some jurisdictions refer to malicious prosecution only for a prior criminal proceeding whereas vexatious litigation would be based on a prior civil proceeding. It is considered an abuse of the judicial system as it is filed with ill intention to harass, defame, or harm the innocent party.

Wrongful prosecution is often the precursor to wrongful conviction. Wrongful prosecution represents cases where harm is inflicted on an innocent person through the criminal process, but the individual may be acquitted or have the case dismissed before conviction; these are often called "near misses". Wrongful convictions entail a deeper level of state error, where the innocent person is not only prosecuted but also convicted and sentenced for a crime they did not commit.

Official Definition of ‘Wrongful Prosecution’

Wrongful prosecution is defined broadly to include cases where there is malicious intent by police or prosecution, lack of reasonable and probable cause for prosecution, or the conduct by public officials that results in the accused being wrongfully charged or pursued through the criminal justice process. It includes both acquittals after long trials and cases where charges were baseless or pursued in bad faith.

As defined in Legislation

There is no legislative/statutory mechanism that defines wrongful prosecution. However, the existing laws bring three categories of remedies i.e., private, public and criminal law with respect to miscarriage of justice resulting in wrongful prosecution. In the first two remedies, the state provides compensatory relief to the victims who have suffered on account of wrongful prosecution whereas the third remedy holds the wrongdoer accountable i.e., proceedings against the concerned officers of the state for their misconduct.

Legal Provision Relating to Wrongful Prosecution

India has no effective statutory or legislative mechanism for wrongful prosecutions due to police and prosecutorial misconduct. At present, relief for those acquitted after wrongful prosecution depends on sporadic judicial interventions (such as compensation under Article 21 by constitutional courts) or pursuing civil claims for compensation through tort actions like malicious prosecution, which are neither timely nor accessible for most victims. There is no concrete mechanism in existing laws like the Bharatiya Nagrik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS) 2023 (erstwhile Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973) to ensure systematic compensation, rehabilitation, and reintegration for those wrongfully prosecuted and incarcerated.

Private Law

The private law remedy for errant acts of State officials exists in the form of a civil suit against the State for monetary damages. The Supreme Court has time and again emphasised the above-discussed Constitutional remedy of a claim based on strict liability of the State is distinct from and in addition to the remedy available in private law for damages on account of tortious acts of public servants especially negligence by a public servant in the course of employment. In State of Bihar v. Rameshwar Prasad Baidya[2], the SC held that the State is liable to pay damages to the accused person for his malicious prosecution by State employees.

However, given the nature of civil litigation and the expenses like court fees and other litigation costs, this remedy is not victim-friendly.[3]

Public Law

The public law remedy for miscarriage of justice on account of wrongful prosecution, incarceration or conviction is rooted in the Constitution of India. In such cases, it is the violation of fundamental rights under Article 21 and Article 22 that invokes the writ jurisdiction of the Supreme Court and High Court under Article 32 and 226 of the Constitution respectively. It entitles the victim to be compensated who may have suffered detention or bodily harm at the hands of the state employees. In a catena of judgments, the SC has held the state’s vicarious liability to pay monetary compensation for the tortuous acts of its employees. These judgments established pecuniary compensation as a public law remedy for the violation of fundamental rights. However, most of the Subordinate Courts refrain from granting monetary relief and taking action against corrupt officers.

Criminal Law

The criminal law remedy focuses on the wrongdoers i.e. the concerned public officials. The provisions contained in the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) and the Bharatiya Nagrik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS) lay down the substantive and procedural contours of the actions that can be taken against the wrongdoers.

Bharatiya Nagrik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS) 2023

The Bharatiya Nagrik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS) 2023 provides safeguards to protect judges and public servants from vexatious litigation with respect to their actions while performing a public function. Section 151 and 218 of Bharatiya Nagrika Suraksha Sanhita, 2023 (BNSS) (Sections 132 and 197 of CrPC) mandate sanction of the government before any criminal proceedings are instituted against a police officer alleged to have committed a criminal offence while discharging the official duty.[4] In addition to these provisions, there are also similar procedural safeguards for the police under a few of the States’ Police Acts and the Rules thereunder. Another Section 399 of BNSS (Section 358 of CrPC) is to be noted that provides for compensation to persons groundlessly arrested but there should be evidence to indicate that the informant caused the arrest of the accused without any sufficient cause.[5] The person at whose instance the arrest was made may be ordered to pay compensation of a maximum of 1000 rupees to the person arrested which hardly makes it a relief for the wrong done.

Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) 2023

Under the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) 2023, Chapter XII Of "Offences by or Relating To Public Servants" deals with offences which can be committed by public servants and the offences which relate to public servants, though not committed by them.[6] With respect to the issue under consideration, Section 198 of Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) (previously section 166 of IPC) deals with disobedience of any direction of law in a general sense with an intent to cause an injury to a person and Section 199 of Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) (previously section 167 of IPC) deals with a particular instance of a public servant framing an incorrect document with intent to cause injury.[7]

- Section 198 punishes public servants who knowingly disobey legal instructions with intent or knowledge that it may cause injury. Such disobedience could lead to wrongful actions, including failing to properly investigate or disclose evidence, thus contributing to wrongful prosecution.

- Section 199 punishes public servants who wilfully neglect or omit their lawful duties causing or likely to cause harm. This includes failure to carry out essential investigatory or procedural duties that safeguard the accused’s rights, potentially resulting in wrongful prosecution.

- Section 201 punishes framing incorrect documents by public servants with intent or knowledge of harm. Manipulation or falsification of official records—like charge sheets, investigation reports, or evidence—can directly cause wrongful conviction or prosecution.

Further, Chapter XIV titled “of false evidence and offence against public justice’ also deals with disobedience on the part of public servants in respect of official duty.[8] There are 44 sections relating to giving and fabricating false evidence Section 227 to 237 of Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (2023) (previously Sections 191 to 200 of IPC ) and offences against public justice Section 238 to 268 of Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (2023) (previously Sections 201 to 229).[9] The sections contained in these chapters together list offences that provide possible instances of police, investigating agency and prosecutorial misconduct concerning an investigation, prosecution, trial and other criminal proceedings.

One of the most important sections with respect to the miscarriage of justice resulting in wrongful prosecution is Section 248 of Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) (previously Section 211 of IPC).[10] This section is interpreted to be specifically applicable to investigating agencies including the police when they bring a false charge of an offence with an intent to injure.

As defined in Official Government Reports

Law Commission Reports

277th Law Commission Report

The Law Commission of India submitted its 277th Report titled “Wrongful Prosecution (Miscarriage of Justice): Legal Remedies on 30th August 2018. According tot he report, Wrongful Prosecution are the cases of miscarriage of justice where procedural misconducts - police or prosecutorial, malicious or negligent – resulted in wrongful prosecution of an innocent person, who was ultimately acquitted, with a court making an observation or recording a finding to that effect. The underlying sentiment being that such person should not have been subjected to these proceedings in the first place.

The report recommends ‘wrongful prosecution’ to be the standard of a miscarriage of justice as against ‘wrongful conviction’ and ‘wrongful incarceration’. It defined wrongful prosecution as including cases where the accused is not guilty of the offence, and the police and/or the prosecution engaged in some form of misconduct in investigating and/ or prosecuting the person. It would include both the cases where the person spent time in prison as well as where he did not, and cases where the accused was found not guilty by the trial court or where the accused was convicted by one or more courts but was ultimately found to be not guilty by the Higher Court.[11]

The report also provided an illustrative list of procedural misconduct would include the following:

- (i) Making or framing a false or incorrect record or document for submission in a judicial proceeding or any other proceeding taken by law; (ii) Making a false declaration or statement authorized by law to receive as evidence when legally bound to state the truth - by an oath or by a provision of law; (iii) Otherwise giving false evidence when legally bound to state the truth - by an oath or by a provision of law; (iv) Fabricating false evidence for submission in a judicial proceeding or any other proceeding taken by law; (v) Destruction of an evidence to prevent its production in a judicial proceeding or any other proceedings taken by law; (vi) Bringing a false charge, or instituting or cause to be instituted false criminal proceedings against a person; (vii) Committing a person to confinement or trial acting contrary to law; or ( viii) Acting in violation of any direction of law in any other manner not covered in (i) to (vii) above, resulting in an injury to a person.

As defined in Official Documents

Private Member Bills

The Protection of Rights of Wrongful Convicts Bill, 2019

This private member bill was introduced by Dr Kirit Premji Bhai Solanki in the Lok Sabha to establish a procedure for safeguarding the rights of wrongful convicts and for matters connected therewith or incidental thereto.[12]

The Protection of Rights of Wrongful Convicts Bill, 2019 seeks to establish a comprehensive legal framework to recognize, protect, and compensate individuals wrongfully convicted and later acquitted by competent courts. The Bill acknowledges wrongful convictions as a grave miscarriage of justice and aims to restore the dignity and rights of such individuals. Its key provisions include the creation of a statutory right to compensation (both monetary and non-monetary), rehabilitation measures such as counseling, legal aid, education, and employment assistance, and the establishment of a Special Court or Authority to assess claims and determine fair compensation. It also mandates a time-bound process for filing and adjudicating claims and emphasizes the State’s obligation to take responsibility for systemic errors that lead to wrongful incarceration.

It also defined wrongful incarceration and wrongful conviction under Section 2(e), "wrongful incarceration or wrongful conviction" means an individual convicted of an offence and who served all or part of the sentence of the offence and was later acquitted for the reasons the individual was innocent or the judgment was reversed and other accusatory evidence was dismissed or prosecution executed without good faith, which concluded in favour of the accused or includes any of the following:

- (i) Making or fabricating a false or incorrect record or document for submission; or

- (ii) making a false declaration or statement before an officer authorized by law to receive as evidence when legally bound to state the truth that is to say by an oath or by a provision of law; or

- (iii) otherwise giving false evidence when legally bound to state the truth that is to say by an oath or by a provision of law; or

- (iv) fabricating false evidence for submission; or

- (v) suppression or destruction of an evidence to prevent its production; or

- (vi) bringing a false charge or instituting or cause to be instituted false proceedings against a person; or

- (vii) acting in violation of any law in any other manner not specifically covered above.

The Code of Criminal Procedure (Amendment) Bill, 2022

This private member bill was introduced by Shri Unmesh Bhaiyyasaheb Patil in the Lok Sabha to amend the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973.[13] The Bill seeks to amend the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 to enhance protections for victims of sexual violence and individuals wrongfully prosecuted. It introduces definitions for “malicious prosecution” and “wrongful prosecution”, expanding accountability for false or bad-faith prosecutions.

The definition of 'wrongful prosecution' as provided in the Code of Criminal Procedure Amendment Bill, 2022 (section 2, clause xa) is the same as that recommended by the Law Commission of India in its 277th Report. Wrongful prosecution is defined as malicious or bad faith prosecution that ends in favor of the accused, and explicitly includes actions like fabricating evidence, bringing false charges, or causing confinement contrary to law, paralleling the Law Commission’s suggested elements and scope.

Other salient features of the bill include:

- Section 357C is expanded to mandate routine mental healthcare for victims of sexual offences, to be provided by qualified mental health practitioners throughout the investigation and trial, requiring written victim consent and oversight by the State Mental Health Authority (Section 357C; amendments and provisos).

- Section 358 increases the maximum compensation for wrongful arrests from ₹1,000 to ₹20,000, and new Sections 358A-358C establish a right to compensation for persons wrongfully prosecuted, allowing claims by accused, agents, or heirs, and providing for interim compensation up to ₹50,000 for long incarcerations (Section 358A). Applications must be made within two years of acquittal, with appeals to the High Court subject to deposit requirements, and rule-making powers given to the government for the new compensation mechanisms (Sections 358A-358C)

- The bill also inserted S. 358A in the amendment act for Application for compensation for wrongful prosecution.

These private member bills proposed comprehensive reforms such as introducing provisions for compensation in cases of wrongful and malicious prosecution, routine mental healthcare for victims of sexual offences, and enhanced remedies for those wrongly arrested. Notably, the Bill’s definition of “wrongful prosecution” closely mirrored the Law Commission’s 277th Report recommendations and would have provided substantial statutory remedies for affected individuals. However, these key provisions were not enacted into law and did not find place in subsequent legislative reforms like the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS), which replaced the CrPC. As a result, the progressive measures for compensation and victim support outlined in this Bill remain unimplemented in India’s current procedural criminal law framework.

As defined in International Instruments

International Covenant on Civil & Political Rights (ICCPR) 1966

International Covenant on Civil & Political Rights 1966 (ICCPR) discusses the obligation of the State in cases of miscarriage of justice resulting in wrongful conviction. The ICCPR focuses on miscarriage of justice broadly, including wrongful conviction, and requires the state to compensate the victim on account of wrongful prosecution. These provisions include

- Article 9(5) of ICCPR which states: “Anyone who has been the victim of unlawful arrest or detention shall have an enforceable right to compensation.”

- Article 14(6) of the ICCPR which states: “When a person has by a final decision been convicted of a criminal offence and when subsequently his conviction has been reversed or he has been pardoned on the ground that a new and newly-discovered fact shows conclusively that there has been a miscarriage of justice, the person who has suffered punishment as a result of such conviction shall be compensated according to law, unless it is proved that the non-disclosure of the unknown fact in time is wholly or partly attributable to him."

Though India has ratified ICCPR, it has not incorporated this obligation into the domestic legal framework.

As defined in Case Laws

Need of legislative framework

Babloo Chauhan v. State Govt. of NCT of Delhi (2017)

The Delhi High Court in Babloo Chauhan case[14] recognised the urgent need for a legislative framework for providing relief and rehabilitation to victims of wrongful prosecution and incarceration and asked the Law Commission to undertake a comprehensive examination of the aforesaid issues to make a recommendation to the government. The court further expressed grave concern about the state of innocent persons being wrongfully prosecuted for crimes that they did not commit.

An Amicus Curie Report[15] submitted by NLU Delhi suggested possible legal remedies for victims of wrongful incarceration and mallicious prosecution in India. The report suggested that a comprehensive assistance scheme for wrongfully prosecuted and incarceration person can be formulated taking into account factors like - a. Recognition of certain rights to be given to wrongfully prosecuted people. b. To envisage the measures of protection against the unfair deal by the criminal justice agencies and the society to the wrongfully prosecuted people. c. Determination of pecuniary and non-pecuniary measures including rehabilitation arrangements to wrongful prosecuted people for the loss of their time as prisoners and the consequences associated with it. This would also require the calculations of financial and non-financial aspects of their victimization. d. Appropriate orders may also be issued to the State Governments to identify and count the exact number of persons likely to be under wrongful prosecution and incarceration. e. The proper documentation of the nature and extent of exonerations resulting from wrongful prosecution may also be undertaken.

Kattavellai Devakar v. State Of Tamil Nadu (2025)

The Supreme Court in Kattavellai Devakar v. State Of Tamil Nadu (2025)[16] highlighted the need to compensate those who have been wrongfully incarcerated for extended periods and observed the lack of any statutory requirements for the same. It observed that the lack of compensation mechanisms for wrongful incarceration raises constitutional questions under Article 21’s guarantee of life and personal liberty. While the Supreme Court refrained from mandating compensation in Kattavellai, its observations suggest that prolonged incarceration followed by acquittal may constitute a violation of constitutional rights that requires legislative redress.

Compensation as Public Law remedy

Bhim Singh, MLA v. State of J&K (1983)

In Bhim Singh, MLA v. State of J&K[17], an MLA was deliberately prevented from attending a session of the Legislative Assembly by arresting and illegally detaining him in police custody. The SC noted that the police officer acted deliberately and mala fide and the Magistrate and the Sub-Judge aided them either by colluding with them or by their casual attitude which resulted in the violation of Articles 21 and 22(2) of the petitioner. It further noted that when a person comes before the court with the complaint that he has been arrested with mischievous or malicious intent, the mischief or malice may not be washed away merely by setting him free. In appropriate cases, the SC has the jurisdiction to award monetary compensation.

Rudul Sah v. State of Bihar & Anr. (1983)

In Rudul Sah v. State of Bihar[18], the Supreme Court granted the writ petition stating that the petitioner’s detention for 14 years is illegal and violative of fundamental rights. It further declared the state’s liability to grant compensatory relief to repair the damage done by its officers to the petitioner’s fundamental rights. The court further observed that this remedy is independent of the rights available under private law in an action based on tort or under criminal law.

Nilbati Behera v. State of Orissa (1993)

The Supreme Court in Nilabati Behera V. State of Orissa[19] underlined the principle that sovereign immunity is not available in an action for compensation for violation of fundamental rights, where the adjudication is under Article 32 and 226 of the Constitution. The Supreme Court further observed that the award of compensation in writ proceedings is a remedy under public law based on strict liability for violating fundamental rights, though available as a defence under private law in an action based on tort.

International Experience

United Kingdom

The UK has incorporated Article 14(6) of ICCPR into its domestic legislation, the Criminal Justice Act 1988 under Part XI subtitled “Miscarriage of Justice''. Sections 133, 133 A and 133 B provide for compensation to a person who has suffered punishment due to wrongful conviction.[20] Further, Section 88 of the UK Police Act, 1996 deals with the ‘Liability for wrongful acts of constables’ which makes the chief officer of police liable in respect of any unlawful conduct of constables under his direction and control in the performance of their functions.[21] For any damages caused, the payment or settlement amount is paid out of police funds.

The Criminal Cases Review Commission (CCRC) is a part of the criminal justice system in the UK to undertake the exercise of review of the cases with the possibility of miscarriage of justice.[22] Any person who believes that they have been wrongly convicted or sentenced can make an application to CCRC, which can gather information related to the case by carrying out its own investigation to find out the truth and thereafter, apply for review of conviction if miscarriage is found.

United States

The USA has also signed the ICCPR. A majority of the states in the US have their State laws providing for compensation to victims of wrongful prosecution. There are two ways that compensation can be claimed – tort claims/civil rights suits/moral bills of obligation and, statutory claims. Given the variety of statutes across jurisdictions grounds for compensations/procedures vary significantly.[23] Currently, 35 states, the federal government, and Washington, DC have statutes that compensate wrongfully convicted individuals, typically offering at least $50,000 per year of wrongful incarceration, with some states providing higher amounts and additional compensation for time spent on death row or post-release supervision. Compensation claims usually require proof by a preponderance of evidence that the claimant did not commit the crime, and most states have courts adjudicate these claims. Alongside financial payments, many states offer non-monetary benefits such as tuition assistance, counseling, medical support, and housing aid to help exonerees reintegrate into society. Some states also impose offsets to prevent duplication where exonerees receive civil awards after state compensation.[24]

Canada

Canada has no specific legislation which provides a remedy to wrongfully convicted persons. However, it has laid down guidelines of “Federal/Provincial Guidelines on Compensation for Wrongful Convicted and Imprisoned Persons” in consonance with the ICCPR.[25] The guidelines lay down the eligibility criteria along with the procedure of determining the quantum of compensation. The compensation includes both pecuniary and non-pecuniary losses. An individual who crosses the eligibility test under these guidelines can also avail of the expenses incurred during the wrongful conviction, verdict, and demand for pardon.

Germany

In Germany, the law of wrongful prosecution integrates constitutional, civil, and criminal procedural provisions to ensure compensation and state liability for wrongful convictions and administrative faults by officials. Under Article 34 of the Basic Law (Grundgesetz), public officials are personally liable for breaches of duty, but this liability is generally transferred to the State. Section 839 of the German Civil Code (BGB) further establishes officials' liability for intentional or negligent breaches harming third parties. The Law on Compensation for Criminal Prosecution Proceedings (1971) provides a statutory mechanism for compensating those wrongfully prosecuted or detained, offering fixed lump sums for non-material damages alongside claims for material losses, which must be proved by claimants. The compensation claim is typically evaluated during criminal retrials by the courts and finalized via a judicial-administrative process, with civil court remedies available for disputes on compensation amounts. This legal framework aims to balance official accountability, victim reparations, and the prevention of miscarriages of justice through comprehensive remedies for wrongful prosecution in Germany.[26]

Official Database Related to Wrongful Prosecution

Parliamentary Response

Lok Sabha Unstarred Question No. 540 (4th February 2022)

The Lok Sabha unstarred question dated February 4, 2022, addressed to the Minister of Law and Justice, regarding wrongful prosecution and compensation in India. The Minister responded that the National Crime Records Bureau does not maintain data on the number of wrongfully prosecuted individuals nationwide in the past five years.

Data base by Civil Societies

Death Penalty in India: Annual Statistics Report

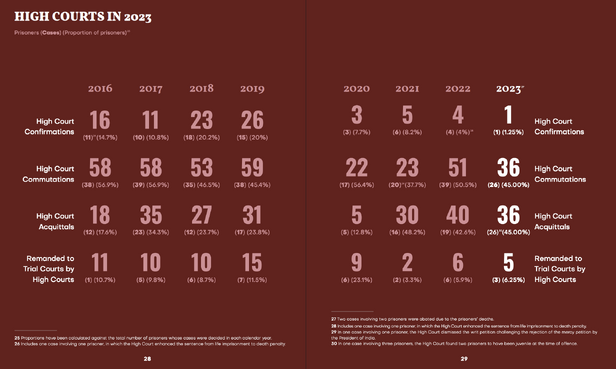

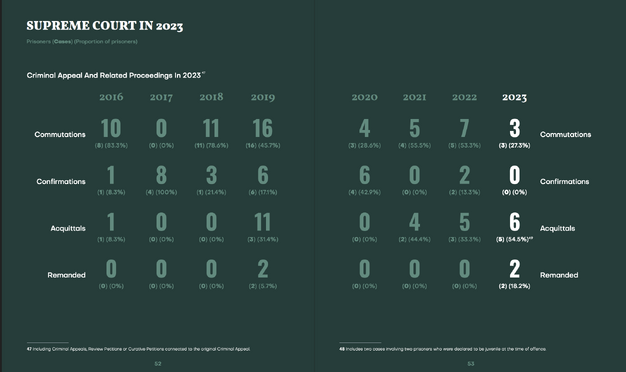

The Annual Statistics Report by P39A provides case level information on Acquittals of accused by SC in HC in death penalty cases.

Innocents Database

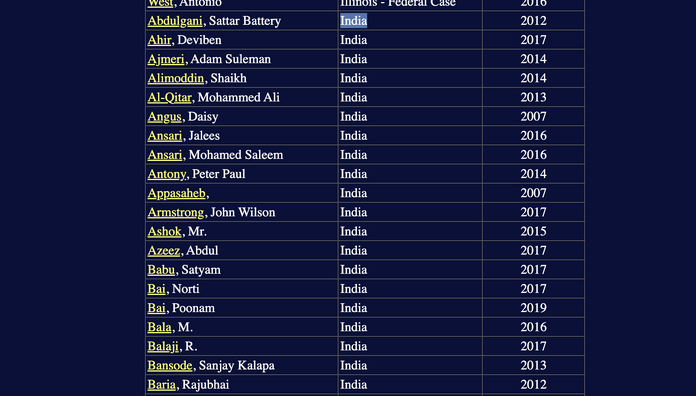

The Innocents Database is a comprehensive global registry documenting over 156,000 cases of exonerations from wrongful convictions across 122 countries as of July 2022. It captures detailed information on cases including demographic data, type of crimes involved (such as homicide, sexual assault, drug offenses), and specific features like sentences received (death penalty, life imprisonment) and posthumous exonerations. The database includes both U.S. cases and a large corpus of cases from other countries, serving as a vital resource for understanding wrongful convictions worldwide.

Research that engages with Wrongful Prosecution

Wrongful Prosecution in Terror Related Cases: A Criminal Law Critique (2018)

This research paper by G. S. Bajpai[27] provides a critical analysis of wrongful prosecution in terror-related cases within the framework of Indian criminal law. The author explores the recurring problem of individuals being wrongfully prosecuted under anti-terror laws, highlighting systemic flaws such as investigative lapses, prosecutorial excesses, and judicial challenges that contribute to miscarriages of justice. Bajpai argues for more stringent safeguards, policy reforms, and accountability mechanisms to prevent wrongful deprivation of liberty in the name of national security, emphasizing the need for a balanced approach between security imperatives and protection of fundamental rights.

Wrongful Convictions, Wrongful Prosecutions and Wrongful Detentions in India (NLSIR)

This research paper by Kent Roach[28] critically examines the phenomenon of wrongful convictions, prosecutions, and detentions in India, with special attention to systemic issues affecting the criminal justice process. Roach highlights both strengths and shortcomings of India's appellate judicial system, noting its willingness to overturn wrongful convictions, particularly in death penalty and terrorism cases, while also observing persistent challenges such as pre-trial detention, false confessions, flawed identification procedures, and lack of robust compensatory mechanisms for victims. The author calls for comprehensive reforms, including improved access to bail, statutory damages for wrongful prosecution and detention, and better judicial powers to challenge state actions—emphasizing that meaningful prevention and reparation require approaches beyond mere compensation, with a focus on addressing institutional failures and promoting equality.

Wrongful Convictions and Institutional Denial (Square Circle Blog)

This blog post by Eesha Shrotriya and Shantanu Pachauri[29] critically examines how wrongful convictions in India are perpetuated by a pattern of institutional denial and systemic dysfunction within the criminal justice system. Drawing from recent Supreme Court cases where longstanding wrongful convictions were overturned, the authors highlight recurring procedural lapses, a culture of performative punishment, and a preference for swiftness and severity over accuracy and fairness. They argue that the absence of formal accountability—such as databases, statutory mandates for compensation, or institutional self-examination—allows entrenched practices and biases to thrive. The blog shows how poor, marginalized defendants are especially vulnerable, and acquittals rarely prompt real reform or recognition of deeper structural issues. The authors call for a cultural and institutional shift through independent review boards, data collection, and compensation mechanisms to anchor justice in procedural safeguards rather than retributive logic.

The Unsettling Landscape of Wrongful Conviction: A Quest for Justice

This research paper by Varsha Gulaya and Dr. K.B. Asthana[30] examines the phenomenon of wrongful convictions within Delhi’s criminal justice system, emphasizing the systemic issues, human errors, and procedural flaws that contribute to miscarriages of justice. The study discusses both historical and contemporary cases, highlighting causes such as eyewitness misidentification, false confessions, inadequate legal representation, unreliable forensic practices, and socio-economic vulnerabilities faced by marginalized groups. It advocates for judicial reforms including fairer police procedures, better trial safeguards, post-conviction review mechanisms, and comprehensive support for reintegrating exonerees into society, in order to restore public trust and uphold the integrity of justice.

"Wrongful Prosecutions and Convictions." Law School Policy Review

This essay by Prof. Kent Roach[31] explores the issue of wrongful convictions and prosecutions with a comparative focus, giving special attention to the Indian context. Roach discusses the recognition of wrongful convictions in various jurisdictions, emphasizing the importance of an equality perspective due to the disproportionate impact on minority and disadvantaged groups. He critiques the Indian criminal justice system’s challenges such as the high number of undertrial prisoners and the limited compensatory mechanisms for victims. The essay highlights the Law Commission of India's novel focus on "wrongful prosecutions" as a promising India-specific approach that emphasizes systemic state responsibilities over individual blame. Roach advocates a holistic reform strategy combining measures to prevent miscarriages of justice along with adequate compensation and judicial activism to protect human rights within the criminal justice system.

Fair Disclosure: An Antidote to Wrongful Prosecution in Indian Criminal Legal System. (Jurist)

This article by Shreya Iyer and Sanchit Khandelwal[32] addresses the critical issue of wrongful prosecution in the Indian criminal justice system, focusing on the absence of a mandatory fair disclosure principle analogous to that in the U.S. and some other common law jurisdictions. The authors argue that the current Indian procedural framework allows the prosecution to withhold exculpatory evidence and self-serving facts, undermining the accused’s right to a fair trial and due process under Article 21 of the Constitution. They advocate for legislative reforms to introduce mandatory pre-trial disclosure obligations in line with international best practices, such as those found in the UK’s Criminal Procedure and Investigations Act 1996 and New South Wales' Director of Public Prosecution Act 1986. The article emphasizes that while compensation for wrongful incarceration is important, prevention of wrongful prosecutions through transparency and procedural fairness is essential to uphold justice and protect human rights.

Compensation for Wrongful Prosecution, Incarceration and Conviction. (Bar & Bench)

This article by S. Sanal Kumar[33] discusses the largely overlooked issue of compensation for victims of wrongful prosecution, incarceration, and conviction in India, highlighting the emotional, social, and economic harms endured by the innocent persons and their families. It reviews international frameworks such as the ICCPR and compares compensation schemes in countries like the UK, the US, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, noting their statutory mechanisms and practical approaches. Indian jurisprudence has recognized compensation under constitutional remedies, but the absence of a uniform statutory framework leads to inconsistent outcomes. The article highlights the 277th Law Commission Report, which recommends statutory compensation for wrongful prosecutions along with the prosecution of errant police officers and advocates for courts awarding compensation at the time of acquittal to ensure timely and adequate redress. It stresses that while monetary compensation cannot restore lost years or dignity, it is an essential step towards justice and reforming criminal justice administration

Books

Compensation for Wrongful Convictions A Comparative Perspective

The book "Compensation for Wrongful Convictions: A Comparative Perspective," edited by Wojciech Jasiński and Karolina Kremens, presents a thorough comparative analysis of both substantive and procedural aspects of compensation for wrongful convictions across various European countries and the USA. It evaluates national compensation schemes in the context of common law, civil law, inquisitorial, and adversarial criminal processes, and discusses the minimum European standard derived from the European Court of Human Rights case law. The work draws important comparative conclusions on the effectiveness and accessibility of these schemes, suggesting an optimum compensation model for the victims of miscarriages of justice. It is an essential resource for students, academics, and policymakers in criminal law and procedure. The book is a product of research by the Digital Justice Center at the University of Wrocław, Poland, under the direction of the editors who are prominent scholars in criminal law.

Challenges and Way Ahead

The legal framework that provides a statutory right to claim compensation from the state to victims of wrongful prosecutions, incarcerations and convictions is absent in India. The latest Prison Statistics of India which is an annual statistical report of the National Crime Records Bureau highlights the fact that as of 31st December 2022, there were 4,34,302 (75.8%) undertrial prisoners of total prisoners in Indian prisons.[34] This leaves scope for innocent under-trial prisoners undergoing prolonged periods of wrongful incarceration. As discussed above in the remedies, the Indian Constitution enables the victims of wrongful prosecution to approach the court for availing compensation and furthermore, the Supreme Court through various landmark judgments has evolved this jurisprudence. Thus, the award of compensation has been recognized as a public law remedy for violations of constitutional rights, including wrongful prosecution. However, it must be noted that it is decided on a case-to-case basis depending on the facts of each case which makes this remedy arbitrary, discretionary and indeterminate.[35] Furthermore, the remedy of compensation creates an ex gratia obligation and not a statutory obligation on the state to compensate. The Indian Judiciary is already overburdened with an excessive number of criminal cases. Hence, it becomes more important to enact a statutory framework for providing compensation to the victim and their family as recommended by the 277th Law Commission Report.

References

- ↑ https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/malicious_prosecution

- ↑ https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1155824/

- ↑ https://www.barandbench.com/columns/compensation-for-wrongful-prosecution-incarceration-and-conviction

- ↑ s. 132, 197 of CrPC (s. 151, 218 of BNSS)

- ↑ s. 358, CrPC (s. 399, BNSS)

- ↑ Ch IX, IPC (Ch XII, BNS).

- ↑ s. 166, 167 IPC (s. 198,199 BNS);

- ↑ Ch XI, IPC (Ch XIV, BNS).

- ↑ s. 191 to 229, IPC (s. 227 to 269, BNS).

- ↑ s. 211, IPC (s. 248, BNS)

- ↑ https://pib.gov.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=183172

- ↑ The Protection of Rights of Wrongful Convicts Bill, 2019; Bill No. 108 of 2019; Lok Sabha Accessible at: https://sansad.in/getFile/BillsTexts/LSBillTexts/Asintroduced/130%20OF%202022%20AS.pdf?source=legislation

- ↑ The Code of Criminal Procedure (Amendment) Bill, 2022; Bill No. 130 of 2022; Lok Sabha Accessible at: https://sansad.in/getFile/BillsTexts/LSBillTexts/Asintroduced/617LS%20As%20Int....pdf?source=legislation#:~:text=The%20Bill%2C%20therefore%2C%20seeks%20to,stigma%20caused%20because%20of%20the

- ↑ Babloo Chauhan @ Dabloo v. State Govt. of NCT of Delhi; 247 (2018) DLT 31 CRL.A.-157/2013; Neutal Citation 2017:DHC:7374-DB

- ↑ Amicus Curie Report: ON WRONGFUL INCARCERATION DEFAULT IN PAYMENT OF FINE SUSPENSION OF SENTENCE A REPORT BY AMICUS CURIAE BEFORE THE HIGH COURT OF DELHI (NLU Delhi)

- ↑ Kattavellai Devakar v. State Of Tamil Nadu 2025 INSC 845 accessible at: https://cdnbbsr.s3waas.gov.in/s3ec055ee0070c40a7c781507b38c59c3e/uploads/2025/08/2025080136.pdf

- ↑ AIR 1986 SC 494

- ↑ Rudul Sah vs State Of Bihar 1983 AIR 1086

- ↑ AIR 1993 SC 1960

- ↑ https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1988/33/part/XI/crossheading/miscarriages-of-justice

- ↑ https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1996/16/section/88/2002-01-01#:~:text=88%20Liability%20for%20wrongful%20acts%20of%20constables.&text=(b)any%20sum%20required%20in,approved%20by%20the%20police%20authority.

- ↑ https://ccrc.gov.uk/#:~:text=The%20CCRC%20is%20the%20very,court%20before%20applying%20to%20us

- ↑ Jasiński, W., & Kremens, K. (Eds.). (2023). Compensation for Wrongful Convictions: A Comparative Perspective. Routledge. Accessble at: Compensation for Wrongful Convictions; A Comparative ...OAPEN Libraryhttps://library.oapen.org › bitstream

- ↑ https://www.law.umich.edu/special/exoneration/Documents/Key-Provisions-in-Wrongful-Conviction-Compensation-Laws.pdf

- ↑ https://cdn-contenu.quebec.ca/cdn-contenu/adm/min/justice/programmes/indemnisation-erreurs-judiciaires/ej_lignes_directrices-a.pdf

- ↑ Albrecht, A. H. (2023). Compensation for wrongful convictions in Germany. In A. A. Editor (Ed.), Compensation for wrongful convictions (pp. 45–60). Taylor & Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003229414-3 available at: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/oa-edit/10.4324/9781003229414-3/compensation-wrongful-convictions-germany-anna-helena-albrecht

- ↑ Bajpai, G. S., Wrongful Prosecution in Terror Related Cases: A Criminal Law Critique (2018). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3182362 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3182362

- ↑ Roach, Kent (2024) "Wrongful Convictions, Wrongful Prosecutions and Wrongful Detentions in India," National Law School of India Review: Vol. 35: Iss. 1, Article 12. DOI: 10.55496/WWQA3810.

- ↑ Shrotriya, Eesha & Pachauri, Shantanu. "Wrongful Convictions and Institutional Denial." Square Circle Blog, September 26, 2025. Available at: https://squarecircleblog.org/2025/09/26/wrongful-convictions-and-institutional-denia

- ↑ Gulaya, Varsha & Asthana, K.B. (2024). The Unsettling Landscape of Wrongful Conviction: A Quest for Justice. Dehradun Law Review, 1(1), 151-164. Available at: https://www.dehradunlawreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/XPS_Law-Review-151-164.pdf

- ↑ Roach, Kent. "Wrongful Prosecutions and Convictions." Law School Policy Review, January 2, 2021. Available at: https://lawschoolpolicyreview.com/2021/01/02/wrongful-prosecutions-and-convictions/.

- ↑ Iyer, Shreya and Khandelwal, Sanchit. "Fair Disclosure: An Antidote to Wrongful Prosecution in Indian Criminal Legal System." JURIST – Student Commentary, June 26, 2020. Available at: https://www.jurist.org/commentary/2020/06/iyer-khandelwal-fair-disclosure-wrongful-prosecution/.

- ↑ Kumar, S. Sanal. "Compensation for Wrongful Prosecution, Incarceration and Conviction." Bar & Bench, accessed September 25, 2025. Available at: https://www.barandbench.com/columns/compensation-for-wrongful-prosecution-incarceration-and-conviction.

- ↑ https://ncrb.gov.in/uploads/nationalcrimerecordsbureau/custom/psiyearwise2022/1701613297PSI2022ason01122023.pdf

- ↑ https://ijlmh.com/paper/right-to-compensation-for-wrongful-prosecution-incarceration-and-conviction-a-necessity-of-the-contemporary-indian-socio-legal-framework/#:~:text='Everyone%20who%20has%20been%20the,'&text='Every%20person%20has%20the%20right,through%20a%20miscarriage%20of%20justice