Corporate Insolvency Resolution Process

Introduction

Prior to the enactment of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC) 2016, the insolvency and winding up of companies in India were primarily governed by the provisions of the Companies Act, 1956, and later by Companies Act, 2013. These legal frameworks included multiple overlapping laws such as The Sick Industrial Companies (Special Provisions) Act, 1985 (SICA); The Recovery Of Debts Due To Banks and Financial Institutions Act, 1993; The Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest Act, 2002. However, this system was widely criticized due to its inefficiencies and complex mechanisms. The absence of a unified framework resulted in significant delays in resolution or liquidation, often leading to the erosion of asset value and increased burden on creditors. Recognizing the need for reform, the Government of India introduced the IBC, 2016. Unlike the earlier framework, which focused predominantly on liquidation, the IBC is resolution-oriented, aimed at ensuring speedy recovery, maintaining credit discipline, and promoting economic growth. The IBC introduced the Corporate Insolvency Resolution Process (CIRP) as a time-bound, creditor-driven mechanism to address financial distress in corporate entities.

Its primary objective is to maximize asset value and promote entrepreneurship by enabling the revival of viable businesses. By replacing previously fragmented and prolonged procedures, the IBC and CIRP ensure speedy redressal, reduce legal uncertainty and foster investor confidence in the Indian economy.

Official Definition of CIRP

CIRP as defined in legislation(s)

The Corporate Insolvency Resolution Process (CIRP) under the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC), 2016, is governed by specific provisions contained within its framework.

Chapter II[1] of the act lays down the procedural aspects of CIRP. It is initiated to resolve the financial stress of the corporate debtor in a time-bound and structured manner, covered in Sections 6 to 32[2] and supplemented by the IBBI (Insolvency Resolution Process for Corporate Persons) Regulations, 2016.

- Initiation (Section 6-10, IBC 2016)[3]

CIRP may be initiated by a financial creditor, operational creditor or the corporate debtor itself upon occurrence of a default.

- Moratorium (Section 14, IBC 2016)[4]

Once admitted, the National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT) imposes a moratorium on all legal actions and asset transfers to ensure stability.

The Interim Resolution Professional (IRP) issues a public announcement, verifies claims and constitutes the Committee of Creditors (CoC) comprising all financial creditors. The CoC exercises key decision-making powers throughout the process, like confirming the IRP as the RP or replacing them through a voting process (Section 22, IBC 2016)[8]

The RP prepares an information memorandum and invites and evaluates resolution plans, which must meet the requirements under Section 30(2), including payments to operational creditors and adherence to applicable laws.

- Approval & Timelines (Sections 31[11] & 12[12], IBC 2016; IBC Amendment Act 2019)

The CoC approves a resolution plan with 66% voting share, followed by NCLT confirmation. Once confirmed, the plan becomes binding on all stakeholders. The entire CIRP must be completed within 180 days, extendable by 90 days and subject to an outer limit of 330 days, including time spent in litigation.

Minimum Default Value

Initially, the minimum threshold for default under the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC) was ₹1 lakh. However, following a government notification issued in March 2020, this threshold was increased to ₹1 crore.

Adjudication Authority under CIRP

The National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT) serves as the Adjudicating Authority in such cases. It exercises territorial jurisdiction over the location of the registered office of the corporate person and is responsible for insolvency resolution and liquidation proceedings concerning corporate entities.[13]

Explanation:

The National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT) is like a specialized tribunal that handles cases related to companies. When a company is not able to pay its debts and someone wants to start the insolvency process, the case is filed in the NCLT.

The NCLT has power only in the area where the company’s registered office is located. So, if a company’s office is in Delhi, the Delhi bench of NCLT will look into the case. It looks after important issues like:

- Starting the insolvency process

- Approving or rejecting the resolution plan

- Company-related disputes, mergers, or winding up

Once NCLT gives a decision, and if someone is not satisfied with it, they can appeal to a higher authority called NCLAT.

NCLAT reviews the decision and may uphold, repeal, or remand the order passed by NCLT.

Relevant Terms

Committee of Creditors (CoC)

As per Section 21[14] of the IBC, 2016, the Committee of Creditors (CoC) consists of all financial creditors of the corporate debtor. The CoC is the primary decision-making body in the CIRP.

It has the authority to:

- Appoint or replace the Resolution Professional (RP)

- Evaluate and approve resolution plans with 66% voting share

- Decide key matters affecting the CIRP

The Supreme Court has affirmed that the CoC's commercial decisions are not subject to judicial review except on limited grounds[15]

Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India (IBBI)

The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India (IBBI) is the statutory regulator responsible for implementing the IBC.

Under Sections 188-196[16] of the IBC, the IBBI:

- Frames regulations for CIRP, liquidation and professional standards

- Registers and supervises Insolvency Professionals (IPs), Insolvency Professional Agencies (IPAs) and Information Utilities (IUs)

- Monitors insolvency processes to ensure compliance.

IBBI plays a central role in maintaining transparency, integrity and accountability in India's insolvency ecosystem.

Information Utility (IU)

As per Sections 209-216[17] of the IBC, 2016, an Information Utility (IU) is an entity that collects, stores, authenticates and provides financial information such as:

- Records of debts

- Evidence of default

- Security interests

IU-authenticated records hold evidentiary value during admission of CIRP applications and help establish default efficiently before NCLT. The IBBI (Information Utilities) Regulations, 2017, govern their functioning.

India currently has one registered IU, regulated by IBBI: National e-Governance Services Ltd. (NeSL)

To Know More: Financial Creditor, Operational Creditor, Corporate Applicant, Committee of Creditors, IBBI, IU

Procedure to file CIRP application

Under the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016, specific documents must be submitted along with the application for initiating the Corporate Insolvency Resolution Process (CIRP), depending on whether the applicant is a financial creditor, operational creditor, or corporate debtor. As per Section 7(3) of the Code read with Rule 4 of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy (Application to Adjudicating Authority) Rules, 2016, a financial creditor is required to submit a record of default from an information utility or any other evidence of default, along with the name of the proposed Interim Resolution Professional (IRP). In the case of an operational creditor, as per Section 9(3) and Rule 6, the application must include a copy of the invoice or demand notice, an affidavit stating that no dispute of the debt exists, and a certificate from a financial institution, or other proof confirming non-payment of the debt, such as records with an information utility. On the other hand, a corporate debtor, as per Section 10(3) and Rule 7, must submit information relating to its books of account, the name of the proposed IRP, and a special resolution passed by shareholders or a resolution passed by at least three-fourths of the total number of partners, approving the filing of the application. These documentation requirements ensure that the insolvency process is initiated with adequate proof, transparency, and internal consent, as applicable to the party initiating the process.

Interim Resolution Process and Stages- Pre Admission Process, Post Admission Process, Liquidation stage

The Corporate Insolvency Resolution Process (CIRP) begins with the pre-admission stage, where a financial or operational creditor, or the corporate debtor itself, files an application before the Adjudicating Authority (NCLT) upon proof of default under the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC), 2016.[18] This admission step appoints an Interim Resolution Professional (IRP), if the application is complete and no dispute is found (in case of operational creditors).[19] The NCLT admits the application within 14 days, marking the start of CIRP.

In the post-admission stage, a moratorium is declared, and the IRP takes over management of the debtor’s affairs.[20] A public announcement is made to invite claims from creditors. Within 30 days, the IRP constitutes the Committee of Creditors (CoC),[21] which takes key decisions, including approval of a Resolution Professional (RP) and evaluation of resolution plans. The entire CIRP must be completed within 180 days, extendable by 90 days.[22]

If no resolution plan is approved within the time frame, the corporate debtor moves into the liquidation stage. In liquidation, a liquidator is appointed, assets are sold, and proceeds are distributed according to the waterfall mechanism under Section 53 of the Code.[23]

Types of CIRP

CIRP

This is the main procedure of the Corporate Insolvency Resolution Process as defined under the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016. This procedure can be initiated through three sub-categorization-

Financial Creditors

As per Section 6[24] of IBC Act 2016, If a corporate debtor fails to pay its dues, the corporate insolvency resolution process (CIRP) can be started by a financial creditor, an operational creditor, or even by the corporate debtor itself, as per the process laid down in the Chapter II of IBC Act 2016.

Any person to whom a financial debt is owed and includes a person to whom such debt has been legally assigned or transferred to is a Financial Creditor.

Section 7[25] of IBC act explains the Initiation of corporate insolvency resolution process by financial creditor as in the event of a default, a financial creditor may start the Corporate Insolvency Resolution Process (CIRP) against a corporate debtor using the procedure outlined in Section 7 of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC), 2016. This clause states that if a default has taken place, a financial creditor may apply to the National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT), the Adjudicating Authority, either alone or in concert with other financial creditors. Evidence of the default, such as loan agreements, account statements, or any other required documentation, must be included with the application. The name of a suggested Interim Resolution Professional (IRP) may also be included, while this is not required.

Within 14 days after receiving the application, the NCLT must decide if it is complete. The NCLT will accept the application and start the CIRP if it is complete and all requirements are Within 14 days after receiving the application, the NCLT must decide if it is complete. The NCLT will accept the application and start the CIRP if it is complete and all requirements are met. The tribunal may, however, reject the application if it contains any errors, although it must give the applicant seven days to correct the errors. Formally, the CIRP starts on the day the application is accepted.

In Addition, it must be noted that as per the Code, Banks, financial institutions, and other lenders are considered financial creditors, as is any individual to whom a financial debt is owed. The inability of the corporate debtor to pay back the financial debt by the due date is referred to as default. Notably, even one creditor has the authority to start the CIRP on their own in situations involving several financial creditors, such as consortium financing. Therefore, Section 7 is essential in allowing creditors to pursue bankruptcy resolution in a systematic and time-bound way.

The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC), 2016, has undergone several reforms to enhance its efficiency and address delays in the corporate insolvency resolution process (CIRP). The latest reform through the IBC (Amendment) Bill, 2025 introduces a significant innovation: The Creditor-Initiated Insolvency Resolution Process (CIIRP). This mechanism represents a shift towards a creditor-driven, out-of-court insolvency resolution model, designed to ensure faster decision-making, minimal judicial involvement, and greater stakeholder confidence.

Concept and Objectives of Creditor Initiated Insolvency Resolution Process

CIIRP allows financial creditors belonging to certain notified classes to initiate insolvency resolution of a distressed company without requiring prior court intervention. Unlike traditional CIRP or pre-packaged insolvency processes, CIIRP is envisioned as a time-bound, creditor-controlled, yet business-friendly mechanism. Its primary objectives are:

- To expedite resolution of genuine business failures.

- To reduce the burden on the National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT)

- To safeguard business continuity with minimal disruption.

- To improve creditor confidence through efficient processes.

Eligibility and Applicability

The initiation of CIIRP is optional and limited to specific cases:

- Eligible Creditors: Only financial creditors belonging to classes notified by the Central Government (e.g., banks, financial institutions) can initiate CIIRP.

- Debtor’s Default: A corporate debtor must have committed default as per Section 4 of the IBC.

- Majority Approval: Creditors representing at least 51% in value of the notified class must approve initiation twice—once before and once after giving the debtor a chance to respond.

- Cooling-Off Period: CIIRP cannot be initiated if the debtor has undergone insolvency proceedings, pre-pack, or CIIRP within the last three years.

Procedure and Initial Steps

The CIIRP process is carefully structured to balance creditor rights with debtor protections:

- Notice to Corporate Debtor: The initiating creditor must notify the debtor and other creditors, allowing at least 30 days for the debtor to settle or respond.

- Second Approval: If no satisfactory settlement occurred creditors again vote (≥51% approval required) to proceed.

- Appointment of Resolution Professional (RP): A registered insolvency professional is appointed by the creditors, without judicial approval.

- Public Announcement: The RP issues a statutory public announcement, which marks the official commencement date of CIIRP.

Expected Impact and Benefits

The introduction of CIIRP is expected to transform India’s insolvency landscape:

- Faster Resolution: Strict 150-day timeline ensures efficiency.

- Reduced Judicial Burden: Out-of-court initiation minimizes NCLT congestion.

- Business Continuity: Management remains operational under RP’s oversight.

- Creditor Confidence: Majority-backed decisions ensure fairness.

- Global Alignment: Incorporation of cross-border and group insolvency norms makes the regime more investor-friendly.

Overall, CIIRP seeks to balance creditor empowerment with debtor protections, thereby strengthening India’s position as a business-friendly jurisdiction. The proposed Creditor-Initiated Insolvency Resolution Process (CIIRP) under the IBC Amendment Bill, 2025, represents a bold step toward efficiency, accountability, and global best practices. By enabling creditors to initiate insolvency with minimal judicial delays, while still allowing debtor management to function, CIIRP promises to create a streamlined, cost-effective, and robust resolution mechanism. Its success will depend on effective implementation, cooperation among stakeholders, and continuous monitoring by regulatory authorities. If executed well, CIIRP could mark a turning point in India’s insolvency regime, enhancing both domestic confidence and global investor trust.

Operational Creditors

Any person to whom an operational debt is owed and including any person to whom such debt has been legally assigned or transferred is known as an operational creditor. Section 8[26] and 9[27] explains the procedure of insolvency resolution by operational creditor as:

First provide the corporate debtor with a demand notice or a copy of the invoice requesting payment in the event of a default. In addition to providing the debtor with a chance to contest the debt or make the required payments, this step acts as an official notification of the default. Then, the corporate debtor has ten days from the date of receipt of the demand notice to reply. Within this time frame, the debtor has two options: either pay back the amount demanded or disclose the existence of an ongoing dispute or proof that the debt has already been settled. The operational creditor may legally start CIRP by submitting an application under Section 9 of the Code with adequate proof, if the corporate debtor does not reply within the allotted time or is unable to provide proof of a legitimate dispute or payment. In a nutshell, Section 8 is important because it guarantees a first assessment prior to the start of insolvency procedures. By shielding corporate borrowers from baseless accusations and giving them a fair chance to resolve conflicts or pay debts, it preserves the harmony between debtors' interests and creditors' rights.

Corporate Applicant

Corporate Applicant means

- corporate debtor

- a member or partner of the corporate debtor who is authorized to make an application for the CIRP under its constitutional document

- an individual who is in charge of managing the operations and resources of the corporate debtor

- a person who has the control and supervision over the financial affairs of the corporate debtor

Section 10[28] explains the procedure of insolvency resolution by corporate applicant as:

The operational creditor may submit an application to the Adjudicating Authority (NCLT) to start CIRP if the corporate debtor does not reply to the demand notice within 10 days, does not pay the amount owed, or raises a legitimate disagreement. The recommended format is required for this application, and it should contain a copy of the invoice or demand notice sent to the corporate debtor, an affidavit confirming that no notice of dispute was received in response, and, if available, a certificate from a financial institution confirming that the payment has not been received. Additionally, the application should contain any other relevant documents or information supporting the claim. The operational creditor may also propose the name of an Interim Resolution Professional (IRP), which is optional but generally recommended to facilitate the initiation of the insolvency process.

In a nutshell, it ensures that operational creditors, after giving the debtor a fair opportunity to respond, can seek a time-bound resolution to recover their dues through the insolvency process. It also maintains safeguards against misuse by requiring proof of default and absence of genuine dispute.

Fast Track CIRP

Fast Track Corporate Insolvency Resolution Process was introduced in India following the Bankruptcy Law Reforms Committee report, which remarked that the timeframe for the insolvency resolution process for certain classes of corporates can be shortened, thereby introducing a new framework. The Insolvency Bankruptcy Code, 2016, introduced the Fast Track Corporate Insolvency Resolution Process (Fast Track CIRP) to address specific needs and streamline the insolvency resolution process of small-scale companies. The objective was to expedite the process and complete the insolvency proceedings of a company in a more efficient manner, with a reduced time frame as compared to the standard corporate insolvency resolution process.

Governing law for the Fast Track Corporate Insolvency Resolution Process

Fast Track CIRP in India is governed by the following legal frameworks:

- Chapter IV of Part II of Code – Section 55 to 58 of the Code[29]

Note: Section 58[30] provides that Chapter II of Part II of the Code, i.e., corporate insolvency resolution process, shall apply to fast track CIRP.

- The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India (Fast Track Insolvency Resolution Process for Corporate Persons) Regulations, 2017 (Fast Track Regulations)[31]

Corporate Debtors eligible for the Fast Track Corporate Insolvency Resolution Process

As per Section 55[32] of the Code, an application for Fast Track Corporate Insolvency Resolution Process can be made in respect of a corporate debtor of the following criteria:

- With income or assets below a specified threshold as may be notified by the central government

- Having a notified class of creditors or amount of debt

- Such other category of corporate persons as may be notified by the central government

Note:

Vide Ministry of Corporate Affairs No. S.O. 1911(E) dated July 14, 2017, the central government notified that the following corporate debtors could file an application for fast-track corporate insolvency resolution process:

1. Small companies

As per Section 2(85) of Companies Act, 2013[33], Small Company is defined as under:

- Other than public company

- Paid up share capital not more than INR 4 crore (or a higher amount as prescribed, not exceeding INR 10 crore)

- Turnover not more than INR 40 crore (or a higher amount as prescribed, not exceeding INR 100 crore)

- The abovementioned criteria shall not apply to:

- a holding company or a subsidiary company

- a company registered under Section 8

- a company or body corporate governed by any Special Act

2. Startups are eligible for Fast Track Corporate Insolvency Resolution Process as well, if they fall within the definition of startup as per government notification issued by the Ministry of Commerce and Industry No. G.S.R. 501(E), dated May 23, 2017.

An entity shall be considered as a startup if it meets the following criteria:

- If it is a private limited company (as defined in the Companies Act, 2013) or a limited liability partnership (under the Limited Liability Partnership Act, 2008) in India.

- Only seven years have passed since its incorporation/registration, or 10 years for biotech companies.

- Turnover since incorporation/registration has never exceeded INR 25 crore.

- Works towards innovation, development or improvement of products or processes or services.

- If it is working towards innovation, development or improvement of products or processes or services, or it is a scalable business model with a high potential of employment generation or wealth creation.

It may be noted that entity formed by splitting up or reconstruction of a business already in existence and partnership firms shall not be considered a startup.

3. An unlisted company with total assets, as per the financial statement of the immediately preceding financial year, not exceeding INR 1 crore.

Steps in Fast Track Corporate Insolvency Resolution Process

Initiation: Section 57[34] of the Code dictates that creditor, or the debtor itself may initiate the process upon submitting an application before the NCLT with proof of existence of default, either with an information utility or such other proofs as notified by IBBI.

Appointment of IRP: The NCLT must appoint the IRP as per the Chapter II of Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India (Insolvency Resolution Process for Corporate Persons) Regulations, 2016.

Public Announcement must happen within 3 days of IRP being appointed. The announcement has to be published in two newspapers: one in English and another in a regional language. Moreover, the announcement has to be posted on the website, if any, of the corporate debtor.

Submission of Claims: The public announcement shall mandate the last date for submission of claims by the applicant which cannot exceed 10 days from the appointment of the interim resolution professional. The IRP shall verify claims within seven days from the last date of the receipt of claims and maintain a list of creditors.

Committee of Creditors: The IRP is required to file a report certifying the constitution of the committee before the Adjudicating Authority within 21 days of the appointment of the IRP. The IRP must file a report under Regulation 17(1) of Fast Track Regulations certifying the constitution of the committee. Along with this report, IRP may apply to the Adjudicating Authority to convert the process to a non-fast track CIRP if IRP is of the opinion that the company does not qualify for a fast-track process. This opinion is based on the records of the company and the claims received. The first meeting of the committee must take place within seven days after the IRP submits the preliminary report. The IRP shall verify claims within seven days from the last date of the receipt of claims and maintain a list of creditors.

Meetings of the committee of creditors: Meetings of the Committee of Creditors (CoC) in a Fast Track Corporate Insolvency Resolution Process shall be in accordance with Chapters VI and VII of the Fast Regulations. However, the CoC may agree to shorter notice periods to facilitate the process.

Appointment of Registered Valuer: The registered valuer must be appointed within 7 days from appointment of the IRP. There is only one Valuer in fast track CIRP as compared to two in non-fast track CIRP.

Due Diligence by RP: The RP shall submit all resolution plans that comply with the provisions of the Code and regulations framed thereunder to the CoC along with his opinion with respect to preferential transactions (Section 43 of Code), undervalued transactions (Section 45 of Code), extortionate credit transactions (Section 50 of Code), and fraudulent transactions. Additionally, copies of orders issued by the adjudicating authority regarding the aforesaid transactions must also be submitted along with the plan, in accordance with Regulation 38(2) of the Fast Track Regulations.

Information Memorandum (IM) and Invitation for Resolution Plan: The resolution professional shall submit information memorandum in electronic form to all the members of CoC within two weeks of his appointment as RP. The IRP/RP should also publish the invitation for resolution plan. There is no stage of inviting Expression of Interest from the prospective resolution applicants preceding the Request for Resolution Plan (RFRP) unlike the standard CIRP.

Resolution Plans: The RP must provide at least 15 days from the publication of Form G to submit the resolution plan. Resolution Plan shall be as per Regulation 36 and 37 of the IBBI (Fast Track Insolvency Resolution Process for Corporate Persons) Regulations, 2016.

Extension of timelines: As per Section 56[35] of the Code, the timeline for completion of Fast Track CIRP is 90 days as compared to 180 days in a standard corporate insolvency resolution process. Further, the fast-track CIRP period can be extended once for an additional period of 45 days. The RP shall file an application before the Adjudicating Authority seeking extension of the period of fast track CIRP subject to the approval of the Committee of Creditors with a majority vote of 75%. If the Adjudicating Authority is satisfied that the process cannot be completed within 90 days, it may issue an order granting an extension of the Fast Track CIRP period.

The Fast Track Corporate Insolvency Resolution Process under the Code is a significant development towards streamlining the insolvency resolution process for specific entities such as small companies and startups in India. The accelerated process not only expedites the resolution but also minimizes the financial strain on startups, allowing them to address their challenges more effectively. Also, a smoother transition through insolvency is encouraged, ultimately supporting the stability and sustainability of the startup ecosystem.

PPIRP

Pre-Packaged Insolvency Resolution Process is another form of insolvency resolution process introduced by IBBI in 2021 specifically Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) and can only be initiated by the corporate debtor with prior approval from 66% of unrelated financial creditors.

In PIRP, the existing management retains control of the business unless there is evidence of fraud or mismanagement. PIRP follows a debtor-in-possession model, unlike the creditor-in-control model of CIRP.

Key difference is the timeline. CIRP must be completed within 180 to 330 days, whereas PPIRP is designed to be faster, with a strict timeline of 90 days, extendable by 45 days. PPIRP also requires a base resolution plan to be prepared before filing, making it more efficient and less disruptive than CIRP, which is a more public and formal process. Overall, while CIRP is suited for large and complex cases, PIRP offers a quicker and cost-effective solution for MSMEs willing to cooperate in resolving their financial distress.

To know more: Pre-Packaged Insolvency Resolution Process

International Experience

United Kingdom (UK)

In the United Kingdom, corporate insolvency and restructuring are mainly governed by the Insolvency Act, 1986[36], the Enterprise Act, 2002[37], and the Insolvency (England and Wales) Rules, 2016[38]. Additionally, the Companies Act, 2006[39] provides the legal framework for schemes of arrangement, while Part 26A introduces the restructuring plan mechanism. The key rescue procedure in the UK is administration, which is aimed at saving the company as a going concern or achieving a better outcome for creditors than liquidation. Once administration begins, an automatic moratorium comes into force, and control of the company shifts from the directors to an appointed administrator. The administrator assesses the company’s financial position, formulates a resolution strategy within a fixed timeline, and places it for creditor approval.

Apart from administration, the UK also uses Company Voluntary Arrangements (CVAs), which enable a binding settlement with creditors based on majority approval. For more complex cases, court-supervised schemes of arrangement and restructuring plans are applied. A significant feature of the 2020 restructuring plan is the introduction of cross-class cram-down, which allows the court to approve a plan even if one class of creditors votes against it. These mechanisms together provide a flexible and creditor-balanced insolvency framework.

United States of America (USA)

In the United States, corporate insolvency resolution is regulated under Chapter 11 of the U.S. Bankruptcy Code[40]. Chapter 11 is the primary legal tool for corporate reorganization. On filing for Chapter 11, an automatic stay is imposed, which halts all recovery actions against the debtor and preserves the company’s assets during restructuring. The debtor is required to submit a detailed disclosure statement along with a reorganization plan specifying how various creditor claims will be dealt with. Creditors vote on the plan, and subject to statutory approval conditions, the court can confirm the plan even if certain classes dissent, through the cram-down mechanism. This court-controlled but management-driven process is widely used for large and cross-border corporate restructurings due to its procedural flexibility and commercial practicality.

Technological Transformation and Initiatives

- Centralized electronic auction/liquidation platform

IBBI has mandated the use of a centralized electronic listing and auction platform for sale of assets under liquidation. As per circulars in 2024–2025, auctions of assets are now managed via this digital platform (formerly known as eBKray, now renamed Baanknet), rather than fragmented offline auctions. This is a major digitization step, helping increase transparency, efficiency, and potentially better realisation for creditors/assets under liquidation.[41]

More can be accessed through: https://baanknet.com/

- Use of technology in courts & global inspiration for digital/AI-based insolvency tools

Legal-tech & court-system digitization have been flagged as game changers for insolvency proceedings. A 2024 article on “Digital Disruption and Debt Resolution” discusses how courts globally (especially in developed jurisdictions) are adopting digital and even AI-assisted tools for insolvency and bankruptcy processes — to handle analytics, scenario modelling, and automate parts of court workflows. While much of this remains external to India’s ecosystem (for now), this global shift provides a blueprint for possible future integration of AI/digital-court-management tools into CIRP/insolvency adjudication.[42]

Appearance of CIRP in Database

Official Database maintained by the government

IBBI Annual Report, 2023-24

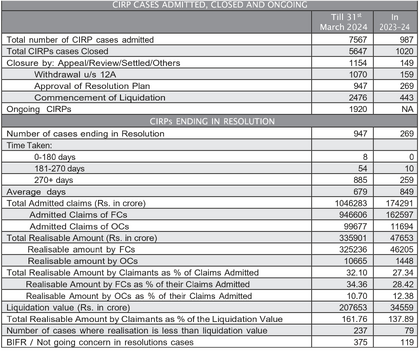

According to data published by the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India (IBBI), the progress of the Corporate Insolvency Resolution Process (CIRP) as of 31st March 2024 and for the financial year 2023-2024 is as follows:

As of 31st March 2024, a total of 7,567 CIRP cases have been admitted, with 987 new cases in FY 2023-24. Out of these, 5,647 have been closed, including 947 resolutions, 1,070 withdrawals under Section 12A, and 2,476 liquidations, while 1,920 cases remain ongoing. The average resolution time has risen to 849 days in 2023-24, well beyond the statutory limit. Total admitted claims stood at 10.46 lakh crore rupees, against which 3.36 lakh crore rupees were realised, reflecting an overall 32% recovery. Financial creditors recovered around 34% of their claims, while operational creditors recovered about 11%. Resolution outcomes continue to yield higher value than liquidation, with recoveries at 161% of liquidation value.

IBBI (Quarterly Newsletter), July - September 2025, Vol. 36

The Code has rescued 3865 CDs (1300 through resolution plans, 1342 through appeal or review or settlement and 1223 through withdrawal) till September 2025. It has referred 2896 CDs for liquidation. The resolved CDs resulted in realisation of more than 32.44% as against the admitted claims and more than 170.09% as against the liquidation value. Resolution plans on average are yielding 93.79% of fair value of the CDs. Till September, 2025, 1529 CDs have been completely liquidated. These 1529 CDs together had outstanding claims of Rs. 4.44 lakh crore, but the assets valued at Rs. 0.17 lakh crore. The liquidation of these companies resulted in 90.70% realisation as against the liquidation value.[43]

- Details of CIRP cases as on September 30, 2025:

| Status of CIRPs | No. of CIRPs |

| Admitted | 8659 |

| Closure: | |

| Withdrawn under section 12A | 1223 |

| Closed on appeal or review or settled | 1342 |

| Resolution plans approved | 1300 |

| Liquidation orders passed | 2896 |

| Ongoing CIRP cases | 1898 |

Note: This excludes 1 CD which has moved directly from Board for Industrial and Financial Reconstruction (BIFR) to resolution.

Source: IBBI (Quarterly Newsletter, July - September 2025; Vol. 36)

2. Outcome of CIRPs, initiated Stakeholder-wise, as on September 30, 2025:[43]

| Outcome | Description | CIRPs initiated by |

| |||

| FCs | OCs | CDs | FiSPs | |||

| Status of CIRPs | Closure by Appeal/Review/Settled | 430 | 899 | 13 | 0 | 1342 |

| Closure by Withdrawal u/s 12A | 378 | 837 | 8 | 0 | 1223 | |

| Closure by Approval of Resolution Plan | 800 | 406 | 90 | 4 | 1300 | |

| Closure by Commencement of Liquidation | 1363 | 1218 | 315 | 0 | 2896 | |

| Ongoing | 1125 | 662 | 110 | 1 | 1898 | |

| Total | 4096 | 4022 | 536 | 5 | 8659 | |

| CIRPs

yielding Resolution Plans |

Realisation by creditors as % of Liquidation Value | 186.16 | 128.64 | 146.89 | 134.9 | 170.09 |

| Realisation by creditors as % of

their Claims |

32.83 | 24.90 | 18.24 | 41.4 | 32.44 | |

| Average time taken for Closure of CIRP | 729 | 739 | 627 | 677 | 725 | |

| CIRPs

yielding Liquidations |

Liquidation Value as % of Claims | 5.42 | 8.33 | 7.48 | - | 6.08 |

| Average Time taken for order of

Liquidation |

526 | 527 | 454 | - | 518 | |

Source: IBBI (Quarterly Newsletter, July - September 2025; Vol. 36)

3. Average Time for Approval of Resolution Plans/Orders for Liquidation:[43]

| Sl. | Average time | As on March, 2024 | As on March, 2025 | July-Sept, 2025 | ||||||

| No. of

Processes covered |

Time | No. of

Processes covered |

Time | No. of

Processes covered |

Time | |||||

| Including

excluded time |

Excluding

excluded time |

Including

excluded time |

Excluding

excluded time |

Including

excluded time |

Excluding

excluded time | |||||

| CIRPs | ||||||||||

| 1 | From ICD to approval of resolution plans by AA | 933 | 675 | 562 | 1195 | 717 | 597 | 105 | 821 | 688 |

| 2 | From ICD to order for Liquidation by AA | 2468 | 492 | NA | 2759 | 507 | NA | 137 | 739 | NA |

| Liquidations | ||||||||||

| 3 | From LCD to submission of final report under Liquidation | 1087 | 604 | NA | 1403 | 645 | NA | 22 | 745 | NA |

| 4 | From LCD to submission of final report under Voluntary Liquidation | 1409 | 410 | NA | 1711 | 401 | NA | 35 | 297 | NA |

| 5 | From LCD to order for dissolution under Liquidation | 706 | 733 | NA | 938 | 778 | NA | 28 | 1054 | NA |

| 6 | From LCD to order for dissolution under Voluntary Liquidation | 959 | 723 | NA | 1218 | 736 | NA | 61 | 872 | NA |

Source: IBBI (Quarterly Newsletter, July - September 2025; Vol. 36, Pg. No. 7-8)

The Code endeavours to close the various processes at the earliest. The 1300 CIRPs, which have yielded resolution plans by the end of September 2025 took on average 603 days (after excluding the time excluded by the AA) for conclusion of process, while incurring an average cost of 1.11% of liquidation value and 0.63% of resolution value. Similarly, the 2896 CIRPs, which ended up in orders for liquidation, took on average 518 days for conclusion. Further, 1529 liquidation processes, which have closed by submission of final reports took on average 668 days for closure. Similarly, 1867 voluntary liquidation processes, which have closed by submission of final reports, took on average 397 days for closure.[43]

To Know More: IBBI (Quarterly Newsletter, July - September 2025; Vol. 36)

Research that engages with CIRP

- Corporate Insolvency Resolution Process (CIRP) Under IBC: An Analysis of Effectiveness and Challenge

A comprehensive assessment of CIRP’s performance reports that as of September 2024, IBC handled approx. 8,002 CIRP cases; highlights that resolution (versus liquidation) outcomes have improved like resolution success rose to approx. 75%. However, the paper also flags serious challenges such as average time for resolution remains very high (≈ 683 days vs target 180 days), and recovery rates for creditors remain low (financial creditors recover approx. 32%, operational creditors approx. 25%).[44]

- Assessing Flaws in the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC) and Proposing Remedies

A critical evaluation of IBC (hence CIRP), focusing on structural and procedural weaknesses: bureaucratic delays, cumbersome claims-filing processes, poor outcomes for operational creditors relative to liquidation value. The paper proposes concrete reforms to improve effectiveness, especially for small/medium creditors.[45]

- The Economic Impact of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC 2016) on Corporate Reconstruction in India

It analyses outcomes of CIRP between 2016 and April 2024. Among 7,813 companies admitted to CIRP, only 1005 were resolved. Of closed CIRPs, 32.59% ended in liquidation, while only 12.86% ended via a resolution plan. The paper underscores the limited success of IBC in achieving corporate revival and suggests need for further reforms.[46]

Challenges

- Delays and Overburdened Adjudication System

A frequent criticism is that many CIRP cases significantly exceed statutory/in-principle timelines. For instance, as of 2025, a substantial portion of ongoing CIRPs, reportedly around 78%, exceed 270 days. The system remains constrained by limited infrastructure, causing backlog in tribunals and hence delaying final resolution or liquidation orders. This delay erodes the value of assets and undermines one of the primary objectives of IBC that is quick resolution and value maximization.[47]

- Low or Sub-optimal Recovery Rates for Creditors

Despite the large number of CIRP cases, actual recoveries remain modest relative to admitted claims. According to one 2025 study, recovery by creditors under many resolution plans remain far below expectations. The study highlights “suboptimal recovery rates” as a fundamental weakness of the IBC regime — especially in liquidation or low-value-asset cases. This weak recovery discourages creditors (especially operational creditors, small suppliers) from relying on CIRP, undermining confidence in the institution.[48]

- Information Asymmetry, Valuation Disputes & Asset-Quality Issues

Complex assets, especially in sectors like real estate, often involve complications like contested land titles, regulatory uncertainty, or cancelled allotments, which create serious obstacles for realistic and transparent valuation. The disputes over valuation methodologies, asset classification, and completeness of asset disclosures often lead to contested claims, delayed plans, or liquidation, reducing overall value recovery. In the absence of sector-specific expertise among insolvency professionals (IPs), especially for real estate, infrastructure or other asset-heavy industries, valuations and resolution plans may not reflect real asset value or workable revival strategies.[49]

- Insufficient Institutional Capacity & Lack of Sectoral Specialization

The recent commentary in 2025 regulatory changes notes that while reforms attempt to improve the system, underlying institutional limitations, especially a shortage of trained personnel and lack of tribunal capacity—are unlikely to be resolved merely by fine-tuning regulations.[47]

Way Ahead

- Expand NCLT/NCLAT benches, fill vacancies quickly and invest in specialized training for members and insolvency professionals.[50]

- Enforce stricter internal timelines for admission and approval of plans, with mandatory reasons recorded for any judicial delay—an approach already reflected in the IBC (Amendment) Bill 2025, which proposes fixed time-limits for approval or rejection of resolution plans and for passing liquidation orders.[51]

- Design CIIRP and pre-pack regulations to encourage very early use, before deep value-destruction, and to make them genuinely accessible to MSMEs and tech/start-up firms.[52]

- Over time, move towards preventive restructuring models (triggered before formal default) in line with practices flagged by PRS (e.g. UK and German systems).[51]

- Fully digitise filings, hearings (where possible) and tracking of timelines for CIRP and liquidation.[53]

- Integrate IBBI, NCLT and Information Utility data so that regulators, courts and stakeholders see a single, live picture of each case—helping spot delays, non-compliance and potential misconduct early.[51]

References

- ↑ The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016, Part II, Chapter II, ss. 6-32A.

- ↑ The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016, Part II, Chapter II, ss. 6-32. https://www.indiacode.nic.in/handle/123456789/2154

- ↑ The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016, Part II, Chapter II, ss. 6-10. https://www.indiacode.nic.in/handle/123456789/2154?view_type=search&col=123456789/1362

- ↑ The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016, Part II, Chapter II, s. 14. https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?abv=CEN&statehandle=123456789/1362&actid=AC_CEN_2_11_00055_201631_1517807328273§ionId=793§ionno=14&orderno=17&orgactid=undefined

- ↑ The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016, Part II, Chapter II, s. 15. https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?abv=CEN&statehandle=123456789/1362&actid=AC_CEN_2_11_00055_201631_1517807328273&orderno=18&orgactid=undefined

- ↑ The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016, Part II, Chapter II, s. 21. https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?abv=CEN&statehandle=123456789/1362&actid=AC_CEN_2_11_00055_201631_1517807328273&orderno=24&orgactid=undefined

- ↑ Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India (Insolvency Resolution Process for Corporate Persons) Regulations, 2016, pg 5, Chapter III, Reg 6 https://ibbi.gov.in/webadmin/pdf/legalframwork/2018/Apr/word%20copy%20updated%20upto%2001.04.2018%20CIRP%20Regulations%202018_2018-04-11%2016:12:10.pdf

- ↑ The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016, Part II, Chapter II, s. 22. https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?abv=CEN&statehandle=123456789/1362&actid=AC_CEN_2_11_00055_201631_1517807328273&orderno=25&orgactid=undefined

- ↑ The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016, Part II, Chapter II, s. 25. https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?abv=CEN&statehandle=123456789/1362&actid=AC_CEN_2_11_00055_201631_1517807328273&orderno=28&orgactid=undefined

- ↑ The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016, Part II, Chapter II, s. 30. https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?abv=CEN&statehandle=123456789/1362&actid=AC_CEN_2_11_00055_201631_1517807328273&orderno=35&orgactid=undefined

- ↑ The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016, Part II, Chapter II, s. 31. https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?abv=CEN&statehandle=123456789/1362&actid=AC_CEN_2_11_00055_201631_1517807328273&orderno=36&orgactid=undefined

- ↑ The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016, Part II, Chapter II, s. 12. https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?abv=CEN&statehandle=123456789/1362&actid=AC_CEN_2_11_00055_201631_1517807328273&orderno=14&orgactid=undefined

- ↑ The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016, s. 60. https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?actid=AC_CEN_2_11_00055_201631_1517807328273&orderno=82#:~:text=(1)%20The%20Adjudicating%20Authority%2C,proceeding%20of%20such%20corporate%20debtor.

- ↑ Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016, s. 21. https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?abv=CEN&statehandle=123456789/1362&actid=AC_CEN_2_11_00055_201631_1517807328273§ionId=800§ionno=21&orderno=24&orgactid=undefined

- ↑ Committee of Creditors of Essar Steel India Ltd. v. Satish Kumar Gupta, (2019) 16 SCC 479.https://corporate.cyrilamarchandblogs.com/2019/11/essar-steel-india-limited-supreme-court-reinforces-primacy-of-creditors-committee-insolvency-resolution/

- ↑ The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016, Part IV, Chapter I & II, ss. 188-196. https://www.indiacode.nic.in/handle/123456789/2154

- ↑ The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016, Part IV, Chapter V, ss. 209-216. https://www.indiacode.nic.in/handle/123456789/2154

- ↑ The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016, ss. 7-10.

- ↑ The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016, s. 9; Mobilox Innovations Pvt Ltd v Kirusa Software Pvt Ltd (2017) 1 SCC 353 (operational creditor dispute test), Available at, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/166780307/

- ↑ The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016, ss. 13-14.

- ↑ The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016, s. 21

- ↑ The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (Amendment) Act 2019; Committee of Creditors of Essar Steel India Ltd v Satish Kumar Gupta (2019) 16 SCC 479.

- ↑ The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016, ss. 33-53.

- ↑ The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016, s. 6, https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?abv=CEN&statehandle=123456789/1362&actid=AC_CEN_2_11_00055_201631_1517807328273§ionId=785§ionno=6&orderno=6&orgactid=undefined

- ↑ The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016, s. 7, https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?abv=CEN&statehandle=123456789/1362&actid=AC_CEN_2_11_00055_201631_1517807328273&orderno=7&orgactid=undefined

- ↑ The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016, s. 8, https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?abv=CEN&statehandle=123456789/1362&actid=AC_CEN_2_11_00055_201631_1517807328273&orderno=8&orgactid=undefined

- ↑ The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016, s. 9. https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?abv=CEN&statehandle=123456789/1362&actid=AC_CEN_2_11_00055_201631_1517807328273&orderno=9&orgactid=undefined

- ↑ The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016, s. 10. https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?abv=CEN&statehandle=123456789/1362&actid=AC_CEN_2_11_00055_201631_1517807328273&orderno=10&orgactid=AC_CEN_2_11_00055_201631_1517807328273

- ↑ The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016, Part II, Chapter IV, ss. 55-58, available at:https://www.indiacode.nic.in/handle/123456789/2154?view_type=search&col=123456789/1362

- ↑ The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016, Part II, Chapter IV, s. 58, available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?abv=CEN&statehandle=123456789/1362&actid=AC_CEN_2_11_00055_201631_1517807328273&orderno=80&orgactid=undefined

- ↑ The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India (Fast Track Insolvency Resolution Process for Corporate Persons) Regulations, 2017, available at: https://ibbi.gov.in/uploads/meetings/Agenda%2029_29_05_2017.pdf

- ↑ The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016, Part II, Chapter IV, s. 55, available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?abv=CEN&statehandle=123456789/1362&actid=AC_CEN_2_11_00055_201631_1517807328273&orderno=77&orgactid=undefined

- ↑ The Companies Act, 2013, Chapter I, s. 2, available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?abv=CEN&statehandle=123456789/1362&actid=AC_CEN_22_29_00008_201318_1517807327856§ionId=185§ionno=2&orderno=2&orgactid=AC_CEN_22_29_00008_201318_1517807327856

- ↑ The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016, Part II, Chapter IV, s. 57, available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?abv=CEN&statehandle=123456789/1362&actid=AC_CEN_2_11_00055_201631_1517807328273&orderno=79&orgactid=undefined

- ↑ The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016, Part II, Chapter IV, s. 56, available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?abv=CEN&statehandle=123456789/1362&actid=AC_CEN_2_11_00055_201631_1517807328273&orderno=78&orgactid=undefined

- ↑ The Insolvency Act,1986, available at: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1986/45/contents

- ↑ The Enterprise Act, 2002, available at: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2002/40/contents

- ↑ The Insolvency (England and Wales) Rules, 2016, available at: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2016/1024/contents

- ↑ The Companies Act, 2006, available at: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2006/46/contents

- ↑ Chapter 11 - Bankruptcy Basics US, available at: https://www.uscourts.gov/court-programs/bankruptcy/bankruptcy-basics/chapter-11-bankruptcy-basics

- ↑ Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India, (Circular No. IBBI/LIQ/84/2025), 28th March 2025, available at: https://ibbi.gov.in//uploads/legalframwork/2025-03-28-235256-5phy7-b74b8337a8b16af1af694dc969a6d1f3.pdf

- ↑ Shivangi Gupta, "Digital Disruption and Debt Resolution: A new Paradigm" (IBC Law Blog, 16 December 2024), available at: https://ibclaw.blog/digital-disruption-and-debt-resolution-a-new-paradigm/? (last visited on 1st December 2025)

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 43.3 IBBI, Quarterly Newsletter, July - September 2025, Vol. 36, available at: https://ibbi.gov.in/uploads/publication/452d899ae03283f1eb40b1bf7ee5f187.pdf (last visited on 1st December 2025)

- ↑ Rajat Sharma and Bhawna Arora, "Corporate Insolvency Resolution Process (CIRP) under IBC: An Analysis of Effectiveness and Challenge" (Indian Journal of Law and Legal Research, vol VII, issue III, 2024), ISSN 2582-8878, available at: https://www.ijllr.com/post/corporate-insolvency-resolution-process-cirp-under-ibc-an-analysis-of-effectiveness-and-challenge?(last visited on 1st December 2025)

- ↑ Jivitesh Singh and Shauktika Shashwat,"Assessing Flaws in the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC) and Proposing Remedies for Enhanced Efficacy: Focus on Bureaucracy, Claims Filing, and the Connection between Operational Creditors and Liquidation Value" (SSRN, 14 May 2025), available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5250973 (last visited on 1st December 2025)

- ↑ Anupam Verma, Nidhi Maurya and Neelam Maurya, "The Economic Impact of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC) 2016 on Corporate Reconstruction in India" (4th Annual International Undergraduate Finance Research Conference (IUFR-C 2024), Sri Lanka, January 2025) DOI: 10.5281/zendo 14717544, available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/392223718_The_Economic_Impact_of_the_Insolvency_and_Bankruptcy_Code_IBC_2016_on_Corporate_Reconstruction_in_India (last visited on 1st December 2025)

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Tushar Pundir and Riddhi Pandey, "IBBI’s recent CIRP reforms: Analysis of India's evolving corporate insolvency regime" (Bar & Bench, 5th July 2025), available at: https://www.barandbench.com/columns/ibbis-may-2025-cirp-reforms-a-critical-analysis-of-indias-evolving-corporate-insolvency-regime? (last visited on 1st December 2025)

- ↑ Maniar, Ms. & Varashti, Dr. (2025), "Unveiling Key Challenges in the IBC: A Critical Study of Loopholes and Structural Issues in India’s Insolvency Framework" (International Journal of Environmental Sciences. 11. 128-137. 10.64252/c6zsn811), available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/393414946_Unveiling_Key_Challenges_In_The_IBC_A_Critical_Study_Of_Loopholes_And_Structural_Issues_In_India%27s_Insolvency_Framework (last visited on 1st December 2025)

- ↑ Abhay Shrotiya, "Streamlining Real Estate Insolvency: IBBI’s Blueprint for Transparent, Inclusive Resolutions" July, 2025, (SCC ONLINE TIMES), available at: https://www.scconline.com/blog/post/2025/07/09/streamlining-real-estate-insolvency-ibbis-blueprint-for-transparent-inclusive-resolutions/? (last visited on 1st December 2025)

- ↑ Ministry of Finance, ‘Highlights of Economic Survey 2024–25’ (Press Information Bureau, 31 January 2025), available at:https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=2097919®=3&lang=2 (last visited on 1 December 2025)

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 51.2 PRS Legislative Research, The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (Amendment) Bill, 2025 – Bill Summary (PRS India, 2025), available at:https://prsindia.org/files/bills_acts/bills_parliament/2025/The_Insolvency_and_Bankruptcy_Code_%28Amendment%29_Bill%2C2025.pdf? (last visited on 1st December 2025)

- ↑ PRS Legislative Research, The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (Amendment) Bill, 2025 – Bill Summary (PRS India 2025); Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India, Discussion Paper on Strengthening the Framework for Pre-Packaged Insolvency Resolution Process for MSMEs (IBBI 2025); Ministry of Finance, Economic Survey 2024–25 (Government of India 2025) ch. 3.

- ↑ PMF IAS, ‘Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC): Successes & Challenges’ (30 November 2025), available at: https://www.pmfias.com/ibc/? (last visited on 1 December 2025)